Chapter 13 Chronic generalised anxiety

CLASSIFICATION, EPIDEMIOLOGY AND AETIOLOGY

Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) is diagnosed in people with excessive worry and anxiety, which the person finds difficult to control. Somatic complaints and sleeping problems often accompany the anxiety. According to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, in addition to uncontrollable worrying, there must also be at least three of six somatic symptoms (restless, fatigue, concentration problems, irritability, tension or sleep disturbance), occurring for a period of at least 6 months.1 For a diagnosis of GAD to be reached, significant distress or impaired functioning from the condition must be present. As in MDD, a number of exclusion criteria must also be ruled out (for example, symptoms must not be confined to features of another mental disorder or due to substance use or general medical conditions). Occasional worry and situational anxiety is a normal human experience; true chronic generalised anxiety is a disorder whereby the worrying becomes self-perpetuating and uncontrollable, has a number of distressing somatic features and causes marked impairment of work or social functioning. It should be noted that the diagnosis of GAD is fairly restrictive in terms of the requirement of a long duration and multiple somatic symptoms. As the condition commonly waxes and wanes, the DSM-IV diagnosis may be excessively restrictive in clinical practice.2 A utilitarian diagnosis may involve a period of anxiety or worry that is bothersome to the patient and has occurred for longer than 2 weeks. It is also worth considering that in some people GAD may reflect ‘trait anxiety’—that is, a person whose personality archetype is that of a chronic worrier.

Anxiety disorders are second only to MDD as the most commonly diagnosed psychiatric conditions in primary care,3 with GAD being present in 22% of primary care patients who complain of anxiety problems.4 Consistent with the DSM-IV manual’s description of the 1-year prevalence of GAD as approximately 3%,1 a sample of 10,641 Australians interviewed in 1997 had a 1-month prevalence of 2.8% and a 12-month prevalence of 3.6%.5 Lifetime prevalence of GAD is approximated at around 5–6%.4 Anxiety symptoms are endemic in depression,6 and true comorbidity of depressive and anxious conditions commonly occurs.7,8 Studies have revealed that approximately 60–80% of patients with GAD will suffer from a mood disorder within their lifetimes.9,10 Pure GAD (without other comorbid psychiatric disorders) exists at around 25%.4 The socioeconomic burden of GAD is immense, with sufferers more likely than any other patient group to make frequent medical appointments and use medical resources. In a study of 36,435 GAD patients aged 18 to 64 identified from a claims database, the average total healthcare costs per patient was US$7451.10 Patients with comorbid depression were found to have on average 10% higher costs. As in the case of major depressive disorder, only approximately 40% of sufferers seek treatment and 60% will achieve full or partial remission for over 5 years.11

The pathophysiology of GAD is still uncertain. It appears that GAD has a strong underlying genetic component, which may be triggered into expression by environmental factors.12 Current evidence indicates that the neurobiological influence involves abnormalities of serotonergic, noradrenergic and GABAergic transmission, which is reflected in the efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin and noradrenalin reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and benzodiazepines, which modulate the previously mentioned pathways, respectively.13 Although still not understood, the main neurocircuitry involved in the panic, fear and anxiety response in humans appears to involve the prefrontal cortex, the hippocampus and the amygdala.14 Psychological causes may also exist, for instance a specific cognitive bias to increased attention and misinterpretation of ambiguous stimuli, which are perceived as threatening.11

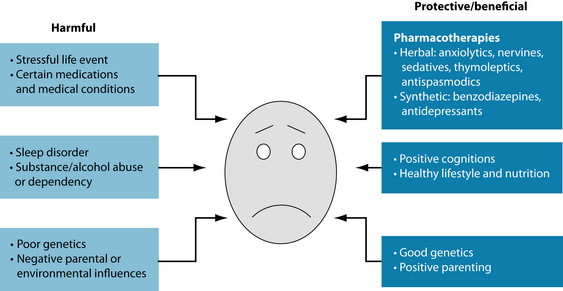

RISK FACTORS

Several risk factors and protective factors exist for GAD (see Figure 13.1). The primary risk factor for developing GAD appears to be genetic.12 Significant familial aggregation also exists, with a strong correlation between the sufferer and a first-order relative with the disorder.15 An anxiogenic familial environment appears also to contribute to the development of the pathology, although the data suggest that genetics are the dominant factor.12 Women are twice more likely to experience GAD than men, and a diagnosis of GAD is uncommon in children and adolescents with the incidence of GAD greatly increasing later in life (onset is usually after 25 years of age).15 As discussed above, comorbidity with depression is common, so it is salient to do a screening for GAD when depressive symptomatology is present. Comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders is more common than not, with an estimated 90% of GAD patients having one or more disorders such as social phobia, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder and bipolar depression.16 In fact, the diagnosis of GAD may be seen as a risk factor for the development of these other psychiatric disorders and also of alcohol and substance abuse disorders.17

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT

Medical treatment of anxiety disorders primarily focuses on pharmaceutical and psychological interventions. Pharmacotherapies include synthetic anxiolytics (for example, benzodiazepines, pre-gabalin, β-blockers and buspirone), and antidepressants (for example, tricyclics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors and SSRIs/SNRIs).18 Current evidence supports the use of both antidepressants and benzodiazepines, with some studies indicating that paroxetine and venlafaxine are the preferable choices. Several issues are present with respect to treatment of anxiety disorders with benzodiazepines. Common side effects include sedation, motor disturbance and cognitive interference (due to GABA-α1,2 agonism), while long-term treatment (> 2 weeks) may cause dependence and withdrawal issues.18,19 Abrupt cessation of benzodiazepines may cause rebound symptoms such as insomnia, agitation and digestive disturbance, and the patient’s anxiety may return to an even higher level than before treatment.19 Psychological interventions include a variety of cognitive, behavioural and interpersonal techniques.11 Combination approaches using psychological and pharmacotherapy treatments are commonly recommended; also, evidentiary support does not currently endorse this approach over using each as a monotherapy.20 The combination does, however, seem to make sense, as pharmacotherapies such as benzodiazepines (or natural alternatives such as Piper methysticum) may elicit an immediate benefit while psychology techniques have been shown to lessen the chance of relapse over the long term.11,20

KEY TREATMENT PROTOCOLS

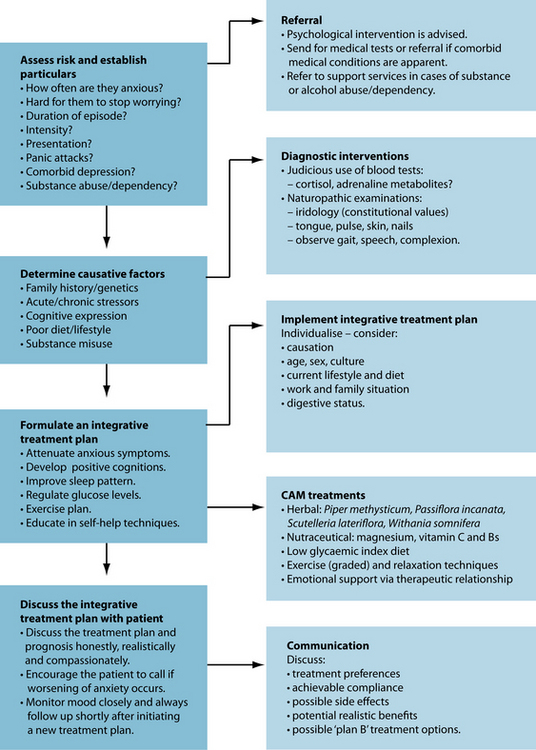

treatment to ameliorate anxiety. Psychological intervention also at this time may be beneficial by working on interpersonal and behavioural skills, and the elimination of anxiogenic self-talk. It is also worth noting that a depressive phase often occurs after an episode of GAD,21 so patient education and prevention strategies are vital. The final main protocol in treating GAD is to educate the patient about self-help interventions they can use to better manage their stress. The use of bibliotherapy, massage, aromatherapy and exercise, and the adoption of calming euthymic activities or hobbies, may also be beneficial (these are reviewed below). While individually each of the aforementioned interventions may possess limited evidence, or have a small clinical effect, the use of many of these self-help techniques in the context of an overall lifestyle pattern may provide a sustained healing effect.

Although the goal is to use evidence-based treatments, it is encouraging to know that any therapeutic interface will commonly promote an anxiolytic effect. Evidence reveals that sufferers of GAD commonly experience other presentations of anxiety such as panic attacks and social phobias.23 Because of this, thorough case taking needs to be employed to assess for any comorbidities. Panic attacks are a severe manifestation of anxiety, and their co-occurrence with GAD or MDD indicates a more severe condition, resulting in a potentially poorer prognosis and more demanding treatment protocol. In the case of comorbid social phobia, behavioural and interpersonal issues need to be explored via an appropriate psychological intervention. As detailed below, several theories and models exist.

GABA pathways and the limbic system

The key biological pathway involved in the presentation and modulation of anxiety disorders involves gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA).11 GABAergic neurones and receptors are involved in the main mode of inhibitory transmission in the central nervous system, and these innervations densely occupy parts of the anxiety/fear-modulating corticolimbic system such as the hippocampus and amgydala.25 GABA-α receptors are the principal target of benzodiazepines, exerting affects such as anxiolysis, sedation and anticonvulsant effects.13 Stimulation of GABAergic pathways also modulates the release of several key neurochemicals (for example, noradrenaline, serotonin and dopamine), although the exact effects are still disputed. Herbal medicines may exert GABA-modulating activity; however, no definitive GABA-α1,2 modulation has been demonstrated to date in humans by any herbal medicines. Valerenic acid from Valeriana officinalis has, however, demonstrated GABA-A receptor (β3 subunit) agonism; this mechanism has been identified as an important pharmacodynamic action responsible for the plant’s anxiolytic and hypnotic action.26

The phytotherapy that has received the greatest attention regarding GABAergic activity is Piper methysticum (kava). Current evidence indicates that kavalactones (the resinoid lipid-soluble constituents found primarily in the root and stem) modulate GABA activity via alteration of lipid membrane structures, and sodium channel alteration, rather than by significant GABA-α1,2 agonism.27–29 Importantly, this activity in animal models was found to occur in the anxiety/fear modulating hippocampus and amygdala. Other neuromodulatory activity effecting anxiolysis are considered to involve

Placebo response is endemic in sufferers of anxiety, with approximately 25% receiving marked benefit from a placebo (dummy) intervention!22

a down-regulation of β-adrenergic activity and MAO-B inhibition.30 Interestingly, inhibition of the re-uptake of noradrenaline in the prefrontal cortex has been demonstrated in animal models.30 This facilitates kava’s unique effect of enhancing mental acuity while relaxing the body and calming the mind. This effect is of a distinct advantage compared to alcohol and benzodiazepines, which cause deleterious cognitive effects. Another advantage of using kava in anxiety disorders is that kavalactones have also demonstrated relaxation of muscular contractibility via modulation of sodium and calcium channels.31 Somatic tension is a common occurrence in anxiety disorders.11

Strong evidence supports the use of kava in treating anxiety disorders. A Cochrane review of 12 randomised, double-blind, controlled trials of rigorous methodology using kava mono-preparations (60 mg–280 mg of kavalactones) in anxious conditions revealed positive results in favour of the phytomedicine.32 A meta-analysis of seven homogenous trials using the Hamilton anxiety scale33 (HAMA) demonstrated that kava reduced anxiety significantly compared to placebo. This effect was supported by another meta-analysis based on six placebo-controlled, randomised trials using a standardised kava extract WS1490 in anxiety (assessed via HAMA).34 Medicinal use of kava is currently restricted in the European Union, and Canada over hepatoxicity.35 The World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended research into ‘aqueous’ extracts of the plant to establish its safety and efficacy in treating anxiety disorders.35 This is in preference to previous acetonic or ethanolic extracts, which may be implicated in hepatoxic reactions. A recent clinical trial sought to assess the effects of an aqueous extract of kava (see the box below).

Other herbal medicines that may affect anxiolysis via limbic system interaction with evidence from human studies include Passiflora incarnata, Scutellaria lateriflora, Melissa officinalis and Ginkgo biloba Passiflora incarnata has traditional usage in the treatment of anxiety and neurosis.37 A Cochrane review of passionflower in the treatment of anxiety included two randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that met inclusion criteria with a total of 198 participants.38 One, a study comparing P. incarnata extract (90 mg/day) to the benzodiazepine mexazolam (1.5 mg/day), revealed no statistical differences in outcome. A trend towards advantage of phytomedicine over the

THE KAVA ANXIETY DEPRESSION SPECTRUM STUDY (KADSS)36

benzodiazepines was noted with respect to decreased sedation and job performance. The other trial included in the review, a pilot RCT using P. incarnata extract on 36 patients with GAD, demonstrated equivalent efficacy of the HM with oxazepam (30 mg/day) in reducing anxiety.39 The herb was determined to cause fewer side effects.40 A recent study using P. incarnata (500 mg) in a controlled study involving 60 patients with preoperative anxiety (90 minutes before surgery) revealed significantly lower anxiety (assessed via a numerical rating scale) in the active group than in the control group.41 No significant differences occurred between other psychological variables, for example recovery and psychomotor function.

The fragrant herbal medicine Melissa officinalis has traditional usage as a mild sedative and an antispasmodic.37,42 A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, balanced crossover experiment involving 18 participants using two separate single doses of a standardised M. officinalis extract (300 mg, 600 mg) and placebo showed that acute dosing of the herbal medicine demonstrated a significant increase in self-rated calmness on a Defined Intensity Stressor Simulation (DISS) test.43 A subsequent crossover RCT using a standardised M. officinalis and Valeriana officinalis product in 24 healthy volunteers demonstrated that a 600 mg dose of the combination lowered anxiety levels compared to control on the DISS.44

Scutellaria lateriflora is a traditional anxiolytic herbal medicine that has been used to treat a variety of nervous system disorders in Native American and eclectic medicine.37 In an animal maze test model, the herb displayed anxiolytic effects, with the compounds baicalin and baicalein purported to be involved in this activity via GABA-α binding.45 A double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study of 19 healthy adults demonstrated that S. lateriflora dose-dependently reduced symptoms of anxiety and tension after acute administration compared to control.40 It should be noted that the methodology of this trial was weak and further research is required to confirm the herb’s efficacy.

While Ginkgo biloba is primarily studied for neuromodulatory activity for the treatment of cognitive conditions, studies have documented mood modulation in cognitively impaired subjects.46 A 2006 RCT involving 82 subjects with GAD using G. biloba EGb 761 extract (480 mg or 240 mg per day) or placebo for 4 weeks revealed a significant dose-dependent reduction of HAMA over placebo in the 480 mg/day and the 240 mg/day G. biloba groups.47

Eschscholtzia californica, Zizyphus jujuba and Valeriana spp. are other plant medicines with encouraging activity; however, to date no human clinical studies have been conducted using these as monotherapies to treat anxiety disorders. Studies are required to validate these traditional uses. Eschscholtzia californica promisingly exerts binding affinity to GABA receptors, with flumazenil (a benzodiazepine receptor antagonist) suppressing these sedative and anxiolytic effects.48 Animal models have revealed that the jujubosides in Zizyphus jujuba inhibit glutamate-mediated pathways (excitory pathway) in the hippocampus.49 Other studies using suanzoaren (a traditional Chinese medicine formula containing Z. jujuba as the principal herbal medicine) in animal models have demonstrated modulation of central monoamines and limbic system interaction.50,51

Magnesium has an important role in neurological activity, and deficiency of the nutrient may cause neuropathologies.52 Magnesium ions regulate calcium ion flow in neuronal calcium channels, helping to regulate neuronal nitric oxide production.53 The deficit of neuronal magnesium ions may be induced by stress hormones, excessive dietary calcium and dietary deficiencies of magnesium.53 Studies using animal models have demonstrated that magnesium deficiency can cause depression and anxiety-like behaviour. After magnesium administration to deficient animals, anxiolytic activity was demonstrated in mice during elevated plus maze and forced swim tests.54 Magnesium appears to exert its anxiolytic effect by the involvement of the NMDA/glutamate pathway, and this activity may involve the glycine(B) sites.55 Interaction between magnesium and benzodiazepine/GABA-α receptors may also be involved in producing anxiolytic-like activity.56 A preliminary controlled study for the relief of mild premenstrual symptoms using combinations of magnesium, vitamin B6, magnesium and vitamin B6, and placebo for one menstrual cycle in 44 women showed no overall difference between individual treatments.57 Further specific subanalyses, however, showed a significant effect of 200 mg/day Mg + 50 mg/day vitamin B6 on reducing anxiety-related premenstrual symptoms (nervous tension, mood swings, irritability or anxiety). Although encouraging, the design of the study and the modest results preclude a firm conclusion of efficacy.

Endocrinological factors

Although not entirely understood yet, the endocrine system has a distinct role in stress and anxiety, with HPA-axis hyperactivation being regarded as a prime component in chronic anxiogenesis.58 CAM interventions that modulate the HPA axis may have a role in treating stress and anxiety (see Section 5 on the endocrine system). Among CAM interventions that may provide HPA-axis modulation are herbal ‘adaptogens’ and ‘tonics’, including Withania somnifera and Rhodiola roseaWithania somnifera is classified in Ayurvedic medicine as a ‘rasayana’, a medicine used to enhance physical and mental performance and ward off disease.59 The plant has been adopted recently into Western herbal materia medica for its use in nervous system and endocrine disorders.42 An animal study observed adaptogenic effects of W. somnifera in a stress-inducing procedure, via the attenuation of stress-related parameters (cortisol levels, mental depression and sexual dysfunction).60 The purported active constituents, the glycowithanolides, were administered orally in an animal model once daily for 5 days, and were discovered to induce an anxiolytic effect comparable to that produced by lorazepam relevant tests (elevated plus maze, social interaction and feeding latency in an unfamiliar environment tests).61

Rhodiola rosea may also have a place in treating generalised anxiety, especially if presenting with fatigue and cardiovascular problems. A small pilot trial used a standardised R. rosea (Rhodax®) formulation in 10 participants with diagnosed generalised anxiety disorder. Participants received 340 mg of Rhodax® in two divided doses for a period of 10 weeks.62 Results demonstrated a significant drop on the Hamilton Anxiety Scale. Although baseline levels on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale were low, a statistically significant response also occurred on this outcome measure. While this study yielded a positive outcome, the uncontrolled design and small sample temper confidence in the results. A caveat that should be observed by clinicians using R. rosea root for anxious presentations is that the herb has (dose-dependently) been found to cause anxiety, irritability and insomnia in some people.

The biological and energetic role of the ‘heart’

Crataegus oxyacantha has traditional use as a phytomedicine to treat cardiovascular complaints and is considered to have heart-tonifying properties.63 Crataegus spp. is usually prescribed in phytomedicine for cardiovascular complaints, an arena in which it possesses robust evidence of efficacy.64,65

Emerging data indicate a use in anxiety, especially where somatic cardiovascular symptoms present (for example, palpitations or tachycardia). An RCT administering 500 mg of hawthorn extract to 36 mildly hypertensive patients measured in a secondary outcome a non-significant trend towards reduction of anxiety, compared with placebo.69

In a later double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial involving participants presenting with mild-moderate GAD (assessed via DSM-III-R) 264 adults were prescribed two tablets containing fixed quantities of Crataegus oxyacantha (300 mg), Eschscholtzia californica (80 mg) and magnesium (300 mg elemental) twice daily for 3 months.70 Total and somatic HAMA scores, subjective patient-rated anxiety and physician’s Clinical Global Impressions scale were used as outcome measures. The results demonstrated that the formula markedly ameliorated anxiety in comparison to placebo as determined by HAMA and subjectively assessed anxiety.

INTEGRATIVE MEDICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Muscular relaxation therapy

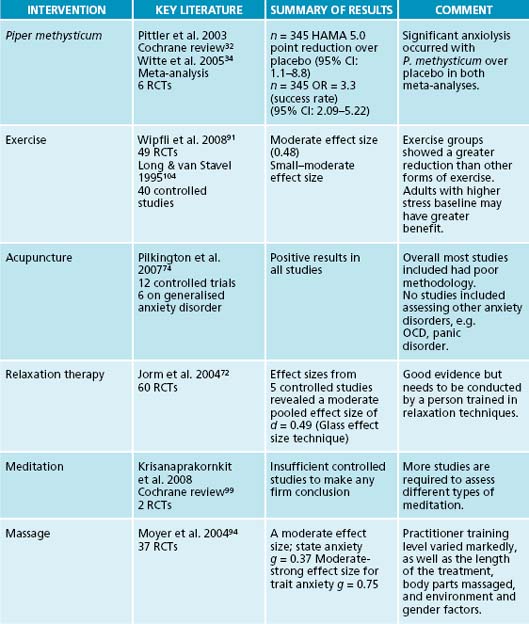

The therapeutic technique of progressive muscle relaxation, developed by Jacobson in 1938, reduces anxiety and stress by first tensing a muscle and then releasing that tension.71 By releasing physical tension the sympathetic nervous system-activated ‘flight or flight’ response may be reduced. This technique may be of value in GAD, which commonly presents with somatic tension. Aside from the physiological relaxation that ensues from progressive muscle relaxation, the technique may have additional anxiolytic benefits by focusing the person’s mind away from worries, and allowing them to develop a sense of self-mastery over their anxiety. Evidence supports the use of muscular relaxation therapy techniques to reduce anxiety and tension. A review of 60 studies concluded that these techniques are as effective as pharmacologic and cognitive techniques.72 A review of the effect sizes from five controlled studies revealed a moderate pooled effect size.

Psychological intervention

As documented in the previous depression chapter, various psychological techniques including cognitive and/or behavioural therapy and interpersonal techniques may be of benefit in treating GAD. Some people may be ‘wired to worry’ via genetic and/or familial upbringing. Although the understanding of people with trait anxiety is limited, it is possible that CAM and pharmaceutical interventions may be only of supportive

value in people who are wired to worry. Techniques that modify anxiogenic behaviours, such as hyperventilation, and assist patients to understand how their thoughts may affect their anxiety and how to alter these cognitive patterns, may reduce the intensity and frequency of the anxiety. While practitioners are encouraged to refer to clinical psychologists or a qualified counsellor they can still employ a ‘person-centred’ approach (empathy, active listening and genuineness) to the therapeutic encounter. A Cochrane meta-analysis was conducted involving 22 controlled studies (1060 participants) using psychological interventions to treat GAD.73 Results based on a subsection of 13 studies using cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) found the technique to be more effective than ‘treatment as usual’ or ‘wait list’ control in achieving a reduction of anxiety. However, six studies comparing CBT against basic supportive therapy revealed no significant difference in clinical response at post-treatment. Psychological therapies based on CBT or interpersonal supportive principles are effective treatments in reducing anxiety.

Acupuncture

A meta-analysis of the efficacy of acupuncture in the treatment of anxiety and anxiety disorders included 12 controlled trials of sufficient methodological standard.74 All trials reported positive findings, but the reports lacked many basic methodological details. Evidence of studies involving perioperative anxiety was generally supportive of acupuncture. Acupuncture, and in particular auricular (ear) acupuncture, was found to be more effective than acupuncture at sham points. The authors note, however, that most results were based on subjective measures and blinding could not be guaranteed. An example of a controlled study of auricular acupuncture involved 67 people with pre-dental operation anxiety using controls, intranasal midazolam, placebo acupuncture, and no treatment.75 The auricular acupuncture group and the midazolam group were significantly less preoperatively anxious compared to the placebo acupuncture group measured on the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory X1.76 Scientific research has found that acupuncture increases a number of central nervous system hormones (adrenocorticotropin hormone, beta-endorphins, serotonin and noradrenaline).77,78

Comorbid presentation of other anxiety disorders

As previously discussed, comorbidity of GAD with other anxiety disorders is the rule, not the exception. Other psychiatric disorders such as depression (unipolar and bipolar), social phobia, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic distress disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) commonly co-exist.79,80 As in the case of major depressive disorder, GAD sufferers with comorbid mental disorders have increased psychological and social impairment, require more treatment and present with a poorer prognosis.23 While specific diagnosis is the domain of psychiatrists and psychologists, it is important that practitioners take a methodical case study to determine more detail beyond the presentation of ‘anxiety’. As illustrated in the box, an initial presentation of ‘stress’ or ‘anxiety’ may be confused with other disorders, for example a depressive disorder, bipolar (hypo)mania, ADHD or OCD or social phobia, or may co-present with other disorders, for example panic disorder.

If the patient presents with an obvious bipolar disorder, delusions or self-harm/suicidality, referral to a medical practitioner or to psychiatric assessment is advised. In the case of co-occurring social phobia, OCD or ADHD, CAM interventions currently do not have firm evidentiary support (although they may have a beneficial adjuvant role). Psychological support to assist in behavioural and cognitive modification may be helpful as part of an integrative solution.

Managing comorbid alcohol and substance abuse or dependence

A common occurrence with anxiety disorders (and depression) is the over-representation of these disorders by sufferers of alcohol or substance overuse.81,82 Practitioners should be aware of this as the overuse needs to be addressed sufficiently before the anxiety disorder can be treated. A basic diagnostic guideline involves differentiating alcohol or drug ‘abuse’ from ‘dependence’. In the former there is a significant pattern of overuse leading to distress or social or work impairment within a 12-month period, and illegal and dangerous activities, and violence; the latter has additional issues such as tolerance, withdrawal, difficulty reducing use and excessive time spent on pursuing the use.1 Alcohol abuse and dependency is common in Western society with a US epidemiological study involving a sample of 43,093 adults revealing that the 12-month prevalence was 17.8% and 12.5% for these disorders, respectively.83

Substance abuse and dependence is a serious problem throughout the world, with alcohol and tobacco being the most commonly abused substances.84 The research and development of pharmacotherapies to treat these have medical, social and economical significance:

Example treatment

Herbal and nutritional prescription

The herbal prescription is designed to primarily exert anxiolytic, nervine tonic and adaptogenic activity.63 Piper methysticum is used as the premier anxiety-reducing herbal medicine. Passiflora incarnata and Scutellaria lateriflora will augment this effect. Withania somnifera will provide a non-stimulating adaptogenic tonic action. The use of Crataegus oxyacantha for the above case will address the cardiovascular presentation of the anxiety (palpitations) and may provide a supplementary anxiolytic activity. Magnesium prescription may be of benefit as an anxiolytic, as his diet is low in the mineral. A multivitamin high in B vitamins may be of benefit in assisting to restore proper adrenal and neurochemical activity.

Dietary and lifestyle advice

Dietary programs designed to treat depression have to date not been rigorously evaluated. Although evidence supporting specific dietary advice is currently absent, a basic balanced diet (see Section 1 on the gastrointestinal system) with foods rich in individual nutrients such as folate, omega-3, tryptophan, B and C vitamins, zinc and magnesium can be recommended. These foods include whole grains, lean meat, deep-sea fish, green leafy vegetables, coloured berries and nuts (walnuts and almonds).52 A low glycaemic index diet may be beneficial in stabilising blood sugar levels, which may in turn reduce the ‘fight or flight’ response of low blood sugar levels (see Section 5 on the endocrine system).

Herbal prescription

| Withania somnífera 1:1 | 40 mL |

| Passiflora incarnata 1:2 | 25 mL |

| Scutellaria lateriflora 1:2 | 20 mL |

| Crataegus oxyacantha 1:2 | 15 mL |

| 7.5 mL b.d. | 100 mL |

| Piper methysticum (50 mg kavalactones) | |

| 2 tablets 2 x day | |

General lifestyle advice should focus on encouraging a balance between meaningful work, adequate rest and sleep, judicious exercise, positive social interaction and pleasurable hobbies. Behavioural therapy techniques have shown positive effects in reducing anxiety by training the person to reduce or better manage stressful situations, and to increase pleasurable activities. These may enhance self-esteem and self-mastery, and increase physical and mental wellbeing. With respect to sleep, insomnia is common in anxiety sufferers (see Chapter 14 on insomnia) and treating this is of primary importance as poor sleep may in turn deleteriously affect neuroendocrine balance and subsequently exacerbate the anxiety. Removal of caffeine from the person’s diet is a vital component to reduce anxiety and improve sleep.89 Caffeine causes arousal, hypervigilance and possible anxiogenesis in certain individuals via stimulation of β-adrenergic receptors and up-regulation of noradrenalin and dopamine; additionally, adenosine receptor antagonism interferes with sleep.90 ‘Decaffeinated’ coffee and tea products still provide for the experience to be had without the sweaty palms and heart palpitations.

Exercise or physical activity

Physical activity is anecdotally regarded as having a positive effect on reducing stress and anxiety, with people often participating in activities such as walking, swimming, cycling doing yoga or going to the gym in order to improve their wellbeing. A recent meta-analysis conducted to examine the effects of exercise on anxiety included 49 studies and showed an overall moderate effect size, indicating larger reductions in anxiety among exercise groups than no-treatment control groups.91 A non-significant trend towards a dose-dependent effect for moderate exercise occurred, while both lower and higher intensity exercise appears less effective. Exercise was found to have a stronger effect than stress management and education, while it was shown as having similar effects to CBT and a slightly less efficacy than pharmacotherapies. Caution should be adopted with anxious people who present with respiratory or cardiovascular symptoms, as these symptoms may be exacerbated with exercise and this in turn may increase anxiety. In some cases respiratory distress may also provoke a panic attack. Graded exercise programs that may be appropriate for anxiety may involve either aerobic or anabolic exercise for a minimum of 20 minutes three to five times per week.

ADDITIONAL PRESCRIPTIVE OPTIONS

Massage

Aromatherapy

Meditation

Expected outcomes and follow-up protocols

In the above case the patient’s anxiety is expected to abate shortly after the commencement of kava, which has a quick onset of activity. The prognosis is better if the course of anxiety is not complicated by comorbid mental disorders or substance abuse, or if there is a history of anxiety.23 The integrative approach involving psychological, dietary/nutraceutical, lifestyle and herbal intervention should offer a sustained benefit if compliance is maintained. Kava should only be prescribed in

KAVA AND THE LIVER

Liver toxicity has been documented from kava usage, and the plant was banned in 2002 in certain countries.35

Hepatotoxicity caused by European kava products may in part be due to a commercial cost-motivated preference for the aerial parts and root or stem peelings, which contain the alkaloid pipermethystine, and due to the use of non-traditional solvents (ethanol and acetone).35

There are various possible causes of hepatotoxicity from kava: a possible interaction with drugs or alcohol, the inhibition of CYP P450 (perhaps especially in the presence of a genetic insufficiency of CYP P450 2D6), reduction of liver glutathione content (or other enzymes needed to metabolise kavalactones) or inhibition of cyclooxygenase enzyme activity.101,102

The use of a water soluble extract of the peeled rootstock of a ‘Noble’ cultivar of kava may be the solution.103

If after 2 weeks of the prescription minimal benefit occurred, kava could be withdrawn and the herbal prescription modified to include other potential anxiolytics, for example Rhodiola rosea, Melissa officinalis, Bacopa monnieri, Valeriana officinalis or Ginkgo biloba. Additional psychological interventions may also be of assistance—behavioural or social-based models to examine and aid in the management of the external triggers of the anxiety.

Jorm A.F., Rodgers B., Blewitt K.A. Effectiveness of complementary and self-help treatments for anxiety disorders. Med J Aust. 2004;181(7 Suppl):S29-S46.

Nutt D.J., et al. Generalized anxiety disorder: comorbidity, comparative biology and treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5(4):315-325.

Sarris J., et al. The Kava Anxiety Depression Spectrum Study (KADSS): a randomized placebo-controlled crossover study using an aqueous extract of Piper methysticum.. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2009;205(3):399-407.

Tyrer P., Baldwin D. Generalised anxiety disorder. Lancet. 2006;368(9553):2156-2166.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

2. Shearer S.L. Recent advances in the understanding and treatment of anxiety disorders. Prim Care. 2007;34(3):475-504. v–vi

3. Antai-Otong D. Current treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2003;41(12):20-29.

4. Wittchen H.U. Generalized anxiety disorder: prevalence, burden, and cost to society. Depress Anxiety. 2002;16(4):162-171.

5. Hunt C., et al. DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Psychol Med. 2002;32(4):649-659.

6. Kessler R.C., et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095-3105.

7. Hunt C., et al. Generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder comorbidity in the National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Depress Anxiety. 2004;20(1):23-31.

8. Sartorius N., et al.Depression comorbid with anxiety: results from the WHO study on psychological disorders in primary health care. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1996(30):38-43.

9. Gorwood P. Generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder comorbidity: an example of genetic pleiotropy? Eur Psychiatry. 2004;19(1):27-33.

10. Zhu B., et al. The cost of comorbid depression and pain for individuals diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder. Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197(2):136-139.

11. Tyrer P., Baldwin D. Generalised anxiety disorder. Lancet. 2006;368(9553):2156-2166.

12. Hettema J.M., et al. A review and meta-analysis of the genetic epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(10):1568-1578.

13. Baldwin D.S., Polkinghorn C. Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of generalized anxiety disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8(2):293-302.

14. Bremner J. Brain imaging in anxiety disorders. Future Drugs. 2004;4(2):275-284.

15. Nutt D.J., et al. Generalized anxiety disorder: comorbidity, comparative biology and treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5(4):315-325.

16. Dunner D.L. Management of anxiety disorders: the added challenge of comorbidity. Depress Anxiety. 2001;13(2):57-71.

17. Kessler R.C..The epidemiology of pure and comorbid generalized anxiety disorder: a review and evaluation of recent research. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2000(406):7-13.

18. Rickels K., Rynn M. Pharmacotherapy of generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(Suppl 14):9-16.

19. Chouinard G. Issues in the clinical use of benzodiazepines: potency, withdrawal, and rebound. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(Suppl 5):7-12.

20. Bandelow B., et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled comparisons of psychopharmacological and psychological treatments for anxiety disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2007;8(3):175-187.

21. Kessler R.C., et al. Co-morbid major depression and generalized anxiety disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey follow-up. Psychol Med. 2008;38(3):365-374.

22. Martin J.L., et al. Benzodiazepines in generalized anxiety disorder: heterogeneity of outcomes based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21(7):774-782.

23. Nutt D., et al. Generalized anxiety disorder: a comorbid disease. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;16(Suppl 2):S109-S118.

24. Mellman T.A. Sleep and anxiety disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;29(4):1047-1058. abstract x

25. Millan M. The neurobiology and control of anxious states. Prog Neuropsychobiol. 2003;70:83-244.

26. Benke D., et al. GABA(A) receptors as in vivo substrate for the anxiolytic action of valerenic acid, a major constituent of valerian root extracts. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(1):174-181.

27. Davies L.P., et al. Kava pyrones and resin: studies on GABAA, GABAB and benzodiazepine binding sites in rodent brain. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1992;71(2):120-126.

28. Yuan C.S., et al. Kavalactones and dihydrokavain modulate GABAergic activity in a rat gastric-brainstem preparation. Planta Med. 2002;68(12):1092-1096.

29. Magura E.I., et al. Kava extract ingredients, (+)-methysticin and (+/–)-kavain inhibit voltage-operated Na(+)-channels in rat CA1 hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience. 1997;81(2):345-351.

30. Singh Y.N., Singh N.N. Therapeutic potential of kava in the treatment of anxiety disorders. CNS Drugs. 2002;16(11):731-743.

31. Martin H.B., et al. Kavain attenuates vascular contractility through inhibition of calcium channels. Planta Med. 2002;68(9):784-789.

32. Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Kava extract for treating anxiety. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2006. CD003383

33. Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32(1):50-55.

34. Witte S., et al. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of the acetonic kava-kava extract WS1490 in patients with non-psychotic anxiety disorders. Phytother Res. 2005;19(3):183-188.

35. Coulter D. Assessment of the risk of hepatotoxicity with kava products. Geneva: WHO appointed committee, World Health Organization; 2007.

36. Sarris J., et al. The Kava Anxiety Depression Spectrum Study (KADSS): a randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial using an aqueous extract of Piper methysticum. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2009;205(3):399-407.

37. Felter HW, Lloyd JU. King’s American dispensatory. Online. Available: http://www.henriettesherbal.com/eclectic/kings/extracta

38. Miyasaka L.S., et al. Passiflora for anxiety disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2007;. CD004518

39. Akhondzadeh S., et al. Passionflower in the treatment of generalized anxiety: a pilot double-blind randomized controlled trial with oxazepam. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2001;26(5):363-367.

40. Wolfson P., Hoffmann D.L. An investigation into the efficacy of Scutellaria lateriflora in healthy volunteers. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9(2):74-78.

41. Movafegh A., et al. Preoperative oral Passiflora incarnata reduces anxiety in ambulatory surgery patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Anesth Analg. 2008;106(6):1728-1732.

42. Bone K. A clinical guide to blending liquid herbs: herbal formulations for the individual patient. St Louis: Churchill Livingstone; 2003.

43. Kennedy D.O., et al. Attenuation of laboratory-induced stress in humans after acute administration of Melissa officinalis (lemon balm). Psychosom Med. 2004;66(4):607-613.

44. Kennedy D.O., et al. Anxiolytic effects of a combination of Melissa officinalis and Valeriana officinalis during laboratory induced stress. Phytother Res. 2006;20(2):96-102.

45. Awad R., et al. Phytochemical and biological analysis of skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora L.): a medicinal plant with anxiolytic properties. Phytomedicine. 2003;10(8):640-649.

46. Scripnikov A., et al. Effects of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761 on neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: findings from a randomised controlled trial. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2007;157(13–14):295-300.

47. Woelk H., et al. Ginkgo biloba special extract EGb 761((R)) in generalized anxiety disorder and adjustment disorder with anxious mood: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41(6):472-480.

48. Rolland A., et al. Neurophysiological effects of an extract of Eschscholzia californica Cham. (Papaveraceae). Phytother Res. 2001;15(5):377-381.

49. Zhang M., et al. Inhibitory effect of jujuboside A on glutamate-mediated excitatory signal pathway in hippocampus. Planta Med. 2003;69(8):692-695.

50. Hsieh M.T., et al. Suanzaorentang, an anxiolytic Chinese medicine, affects the central adrenergic an serotonergic systems in rats. Proc Natl Sci Counc Repub China B. 1986;10(4):263-268.

51. Hsieh M.T., et al. Effects of Suanzaorentang on behavior changes and central monoamines. Proc Natl Sci Counc Repub China B. 1986;10(1):43-48.

52. Osiecki H. The physician’s handbook of clinical nutrition, 5th edn. Brisbane: Bioconcepts publishing; 1998.

53. Eby G.A., et al. Rapid recovery from major depression using magnesium treatment. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67(2):362-370.

54. Spasov A.A., et al. [Depression-like and anxiety-related behaviour of rats fed with magnesium-deficient diet]. Zh Vyssh Nerv Deiat Im I P Pavlova. 2008;58(4):476-485.

55. Poleszak E., et al. NMDA/glutamate mechanism of magnesium-induced anxiolytic-like behavior in mice. Pharmacol Rep. 2008;60(5):655-663.

56. Poleszak E. Benzodiazepine/GABA(A) receptors are involved in magnesium-induced anxiolytic-like behavior in mice. Pharmacol Rep. 2008;60(4):483-489.

57. De Souza M.C., et al. A synergistic effect of a daily supplement for 1 month of 200 mg magnesium plus 50 mg vitamin B6 for the relief of anxiety-related premenstrual symptoms: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9(2):131-139.

58. Arborelius L., et al. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in depression and anxiety disorders. J Endocrinol. 1999;160(1):1-12.

59. Rege N.N., et al. Adaptogenic properties of six rasayana herbs used in Ayurvedic medicine. Phytother Res. 1999;13(4):275-291.

60. Bhattacharya S.K., et al. Adaptogenic activity of Withania somnifera: an experimental study using a rat model of chronic stress. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75(3):547-555.

61. Bhattacharya S.K., et al. Anxiolytic-antidepressant activity of Withania somnifera glycowithanolides: an experimental study. Phytomedicine. 2000;7(6):463-469.

62. Bystritsky A., et al. A pilot study of Rhodiola rosea (Rhodax) for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(2):175-180.

63. Mills S., et al. Principles and practice of phytotherapy. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

64. Rigelsky J.M., et al. Hawthorn: pharmacology and therapeutic uses. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59(5):417-422.

65. Pittler M.H., et al. Hawthorn extract for treating chronic heart failure: meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Med. 2003;114(8):665-674. 1

66. Peck M.D., et al. Cardiac conditions. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2008;50(Suppl 1):13-44.

67. Culpeper N. Culpeper’s complete herbal. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Ltd; 1652.

68. Maciocia G. The foundations of Chinese medicine. Singapore: Churchill Livingstone; 1989.

69. Walker A.F., et al. Promising hypotensive effect of hawthorn extract: a randomized double-blind pilot study of mild, essential hypertension. Phytother Res. 2002;16(1):48-54.

70. Hanus M., et al. Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a fixed combination containing two plant extracts (Crataegus oxyacantha and Eschscholtzia californica) and magnesium in mild-to-moderate anxiety disorders. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20(1):63-71.

71. Conrad A., et al. Muscle relaxation therapy for anxiety disorders: it works but how? Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2007;21:243-264.

72. Jorm A.F., et al. Effectiveness of complementary and self-help treatments for anxiety disorders. Med J Aust 4. 2004;181(7 Suppl):S29-S46.

73. Hunot V., et al. Psychological therapies for generalised anxiety disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 24(1), 2007. CD001848

74. Pilkington K., et al. Acupuncture for anxiety and anxiety disorders—a systematic literature review. Acupunct Med. 2007;25(1–2):1-10.

75. Karst M., et al. Auricular acupuncture for dental anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2007;104(2):295-300.

76. Spielberger C., et al. STAI manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970.

77. Samuels N., et al. Acupuncture for psychiatric illness: a literature review. Behav Med. 2008;34(2):55-64.

78. Cabyoglu M.T., et al. The mechanism of acupuncture and clinical applications. Int J Neurosci. 2006;116(2):115-125.

79. Kessler R.C., et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617-627.

80. Biederman J., et al. Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with conduct, depressive, anxiety, and other disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148(5):564-577.

81. Hasin D., et al. Substance use disorders: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) and International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition (ICD-10). Addiction. 2006;101(Suppl 1):59-75.

82. Cargiulo T. Understanding the health impact of alcohol dependence. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(5 Suppl 3):S5. 11

83. Hasin D.S., et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830-842.

84. Uzbay T.I. Hypericum perforatum and substance dependence: a review. Phytother Res. 2008;22(5):578-582.

85. Dean A.J. Natural and complementary therapies for substance use disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2005;18(3):271-276.

86. Feltenstein M.W., et al. The neurocircuitry of addiction: an overview. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154(2):261-274.

87. Coskun I., et al. Attenuation of ethanol withdrawal syndrome by extract of Hypericum perforatum in Wistar rats. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2006;20(5):481-488.

88. De Vry J., et al. Comparison of hypericum extracts with imipramine and fluoxetine in animal models of depression and alcoholism. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;9(6):461-468.

89. Smith A. Effects of caffeine on human behavior. Food Chem Toxicol. 2002;40(9):1243-1255.

90. Nehlig A., et al. Caffeine and the central nervous system: mechanisms of action, biochemical, metabolic and psychostimulant effects. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1992;17(2):139-170.

91. Wipfli B.M., et al. The anxiolytic effects of exercise: a meta-analysis of randomized trials and dose-response analysis. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2008;30(4):392-410.

92. Bender T.S., et al. The effect of physical therapy on beta-endorphin levels. European Journal Of Applied Physiology. 2007;100(4):371-382.

93. Kuriyama H., et al. Immunological and psychological benefits of aromatherapy massage. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2(2):179-184.

94. Moyer C., et al. A meta-analysis of massage therapy research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(1):3-18.

95. Perry N., et al. Aromatherapy in the management of psychiatric disorders. CNS Drugs. 2006;20(4):257-280.

96. Bradley B.F., et al. Anxiolytic effects of Lavandula angustifolia odour on the Mongolian gerbil elevated plus maze. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;111(3):517-525. 22

97. Graham P.H., et al. Inhalation aromatherapy during radiotherapy: results of a placebo-controlled double-blind randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(12):2372-2376.

98. Muzzarelli L., et al. Aromatherapy and reducing preprocedural anxiety: a controlled prospective study. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2006;29(6):466-471.

99. Krisanaprakornkit T., et al. Meditation therapy for anxiety disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (1):2006;. CD004998

100. Goodman W. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:1006-1011.

101. Anke J., et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic drug interactions with Kava (Piper methysticum Forst. f.). J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;93(2–3):153-160.

102. Clouatre D.L. Kava kava: examining new reports of toxicity. Toxicol Lett. 2004;150(1):85-96.

103. Sarris J., et al. wort: current evidence for use in mood and anxiety disorders. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(8):827-836.

104. Long B., et al. Effects of exercise training on anxiety: a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. 1995;7:167-189.