Chapter 35 Chronic fatigue syndrome

OVERVIEW

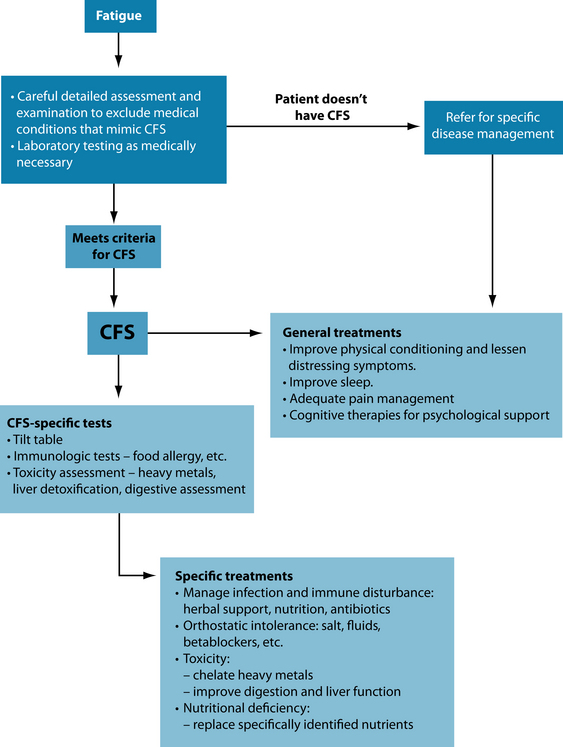

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is a complex yet defined spectrum disorder. It is characterised by expert consensus to include persistent disabling fatigue lasting more than 6 months with other symptoms as listed in the box below. This definition is based upon the USA’s Centers for Disease Control’s description of this illness.1 Importantly there are medical conditions by their nature that may mimic CFS and need to be excluded prior to making an accurate diagnosis. These include untreated thyroid disease, sleep disorders such as sleep apnoea, alcohol abuse, major depressive disorders and schizophrenia. The presence of past and treated malignancy or unresolved infectious hepatitis is also considered exclusive of CFS.1–4 However, the persistence of symptoms despite adequate treatment of the above conditions, including thyroid conditions or infections such as Lyme disease, fibromyalgia and anxiety disorders, may possibly co-exist with a diagnosis of CFS.2 CFS presents significant difficulties in diagnosis and assessment, as there is no single laboratory or clinically significant specific diagnostic test. Patients often appear

CDC CRITERIA FOR THE DIAGNOSIS OF CFS1,2,3,4

clinically well, though express profound deterioration of social and occupational functioning and have significant physical and psychological distress.

AETIOLOGY

Infectious agents

Clinically it is well known that many patients commence their illness after what appears to be an infectious episode. Certainly no single agent has been shown consistently to create all CFS cases; however, the CDC state ‘the possibility remains that CFS may have multiple causes leading to a common endpoint, in which case some viruses or other infectious agents might have a contributory role for a subset of CFS cases, and infection with Epstein-Barr virus, Ross River virus and Coxiella burnetti will lead to a postinfective condition that meets the criteria for CFS in approximately 12% of cases’.4

Immunologic abnormalities

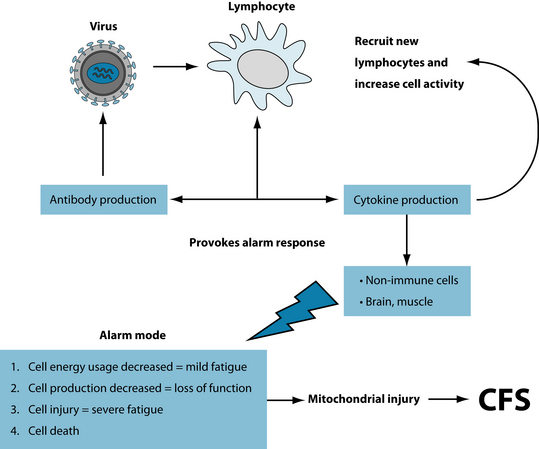

CFS quite possibly may be the result of a complex interplay between an infectious insult and/or a disordered immune response in a susceptible individual. This complexity is revealed in research in the area of immunity and CFS; it clearly has not shown any one consistent abnormality (concerning interleukin abnormalities and altered cell-mediated immunity).11–13 Combined with the consistently observed possibility of multiple infectious aetiological agents and the possibility of persistent or relapsing infections, the resulting immunologic disorders such as elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines ‘may explain some of the manifestations such as fatigue and flu-like symptoms and influence NK activity’.14

Neuroendocrine abnormalities

Hypoactivity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis combined with hyperactivity of the serotonergic system has been postulated as a cause of CFS.15,16 Other research suggests that up-regulation of hypothalamic serotonergic receptors may be the cause some of the HPA disorders—distinctly different from depression17 and ‘adrenal exhaustion’. With respect to the HPA axis, lowered levels of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA, an adrenal steroidal hormone) have been assessed in CFS patients.18 The interplay of dysfunctional immunity, cytokine imbalances leading to subtle neurotransmitter changes is demonstrated in Figure 35.1. Importantly, as mentioned above, depression and its manifestations are distinctly different from CFS both in psychological distress and in physiological dysfunctioning (see Section 4 on the nervous system for treatment details).19

Orthostatic intolerance

Patients with CFS have been shown to have abnormal autonomic responses to prolonged standing or even sitting for long periods.20 This ‘orthostatic intolerance’ manifests as fatigue plus elevated pulse rates, often associated with faintness when the above activities occur. The condition is diagnosable with a severe hypotensive response to ‘tilt table’ testing, where a patient is subjected to a head tilt when lying flat.21

Nutritional causes

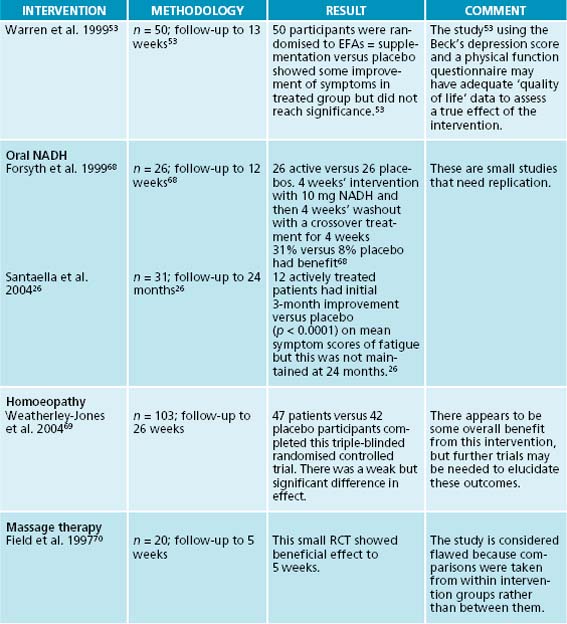

As the diagnosis is defined by the absence of other medical conditions, the fatigue that arises from iron deficiency, vitamin B and B12 deficiency is necessarily excluded as a cause. However, lowered levels of essential fatty acids, L-carnitine and magnesium have been assessed in patients with CFS.17 Interestingly, these nutrients give direct support to mitochondrial function—an essential pathway for the production of cellular energy.22 Empiric research has shown that vitamin B12 injections may improve energy and cognitive ability and mood often with normal serum B12 levels.23,24 Serum folic acid levels have been assayed in patients with CFS and 50% of 60 patients have been shown to have lowered levels.25 Oral nicotinamide (NADH) has been shown in a randomised placebo-controlled trial to give benefit to 31% of CFS patients treated.26

RISK FACTORS

No single risk factor has been strongly associated with CFS. With a spectrum disorder with multiple aetiological factors it seems prudent to individually assess the clinical case as it presents. However study has commenced on what makes a person vulnerable to CFS with the general consensus based upon observation that disordered immunity and infectious agents intervene in a susceptible individual. A summary of the recent researched factors is shown in Table 35.1.

| Older age | Female > male (4:1) |

| Low or middle rather than high educational level | The presence of an anxiety disorder |

| Mood disorder (pre-morbid or 2 months postinfection) | Personality trait—emotional instability |

| Musculoskeletal pain | Low fitness 2 months postinfection |

| Lower physical functioning at baseline assessment | The presence of fatigue at time of viral illness |

| Fatigue severity | Other family members with symptoms of CFS |

Very recent research has revealed that childhood trauma—abuse of sexual or emotional type—may predispose an individual to developing CFS in the presence of other initiating factors.28 Neuroendocrine dysfunction, as discussed in Chapter 15 on adrenal exhaustion, explains how the combination of these factors develop as a definite risk for CFS.29

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT

There remains much contention in some medical services about the existence of CFS, let alone its management. Fatigue is a common presentation to general practice; however, CFS is a unique and separate entity that requires understanding and knowledge of the condition itself and those things that may mimic it. Confusion arises because of the lack of a definitive laboratory test, plus uncertainty about management options available to patients.17 Thus much conventional therapy is directed to symptomatic control of distress in the absence of single or definitive interventions. Key areas of conventional therapy that are summarised in one study30 include:

KEY TREATMENT PROTOCOLS

The primary clinical protocol is to be supportive and patient, and to address the individual needs of the person with CFS. Negotiate a personalised plan recognising the person knows the effect of their illness better than anyone else. The following discussion provides choices that may be individually assessed as appropriate to the person’s needs.

Decrease suffering

Reduce pain and stiffness

Conventional therapies to reduce pain and suffering include regular doses of paracetamol and the use of a nocturnal dose of a tricyclic anti-depressant such as amitryptylline—10–50 mg at night.31,32 Integrative interventions most favoured by people with CFS include massage and chiropractic therapies.33 Recent research suggests that, in the presence of accompanying myofascial pain, manual therapies such as manipulation and myofascial trigger point therapy may have some benefit.34 Nutritional interventions such as magnesium is a nutrient that is an essential cofactor in enzymes of energy metabolism; it acts on muscle tissue as a relaxant (through its calcium channel blocking actions), and also is an essential cofactor in neurotransmitter regulation of pain.35 In CFS it has been used by injection of either magnesium sulfate or oral chelates (such as citrate) at 500 mg two or three times a day to assist pain management.36

Herbal interventions may include combinations of Curcuma longa, Boswellia serrata, Zingiber officinale and Apium graveolens41 with an emphasis on management of pain and stiffness.

Improve sleep

Increase physical conditioning

Graded physical activity

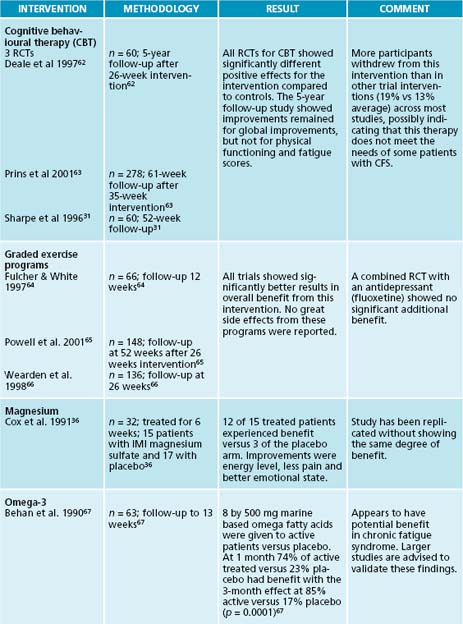

Negotiate a balanced and achievable exercise plan with the patient (after a medical check-up). A graded exercise program supervised by a qualified Health professional e.g. exercise physiologist or equivalent. Two reviews40,42 of research show that, after 3 months of exercise intervention, physical function improved and less fatigue was experienced by those who participated. However improved responses were seen when education was combined with exercise therapy but not when anti-depressants were also used in combination.40 Additionally the exercise intervention may be less palatable to some groups of patients than other interventions.40

Nutritional interventions

Herbal interventions

Herbal treatments for orthostatic intolerance

Improve immune dysfunction

Assess first for allergy and environmental toxicity (see Table 35.2).45,46,54 Dysfunctional immunity has been demonstrated in CFS;55,56 this may manifest as sensitivity to environmental agents such as foods, pollens, dust mites and other agents. Assessment may range from skin prick/patch testing for inhalant allergens, foods and mites to immunoglobulin G testing for food sensitivity.

Table 35.2 Tests for infection, allergy and environmental toxicity45,46

| TESTS | FUNCTIONAL OUTCOME | MANAGEMENT RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|---|

| Assess for infection | Detect any ‘occult’ or latent infections, e.g. Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, Rickettsia, virus or parasites | Requires specialised assessment and advice, but nutritional and herbal immune support can be used as a basis of management |

Nutritional interventions

Herbal interventions

Improve psychological symptoms

Conventional therapies

Nutritional interventions

Example treatment

Prescription

Herbal prescription

| Rhodiola rosea 1:1 | 20 mL |

| Rehmannia glutinosa 1:2 | 30 mL |

| Astragalus membranaceus 1:2 | 35 mL |

| Glycyrrhiza glabra 1:1 | 15 mL |

| 5 mL t.d.s. | 100 mL |

| Withania somnifera 600 mg | |

| Panax ginseng 125 mg 2 tablets b.d. | |

Note: Create a plan. Negotiate this with the patient.

Be flexible—people with CFS have fluctuating symptoms and needs.

Expected outcomes and follow-up protocols

CFS is a chronic condition that may take months to resolve, so patience is required. The patient with CFS has a spectrum of needs. Management of such a spectrum disorder may necessitate different team members at different times in the illness. Such team members may be a psychologist, exercise physiologist, dietician, physiotherapist and massage therapist, even a physician. Note that consideration of orthostatic intolerance may necessitate earlier assessment via tilt table testing. If a positive result is obtained, then additional assessment to exclude hypoadrenal function (fasting salivary cortisol) may be necessary with the addition of salt and fluid loading. Conventional therapy may include the use of a low dose beta-blocker. Interventions that may assist are liquorice, Rehmannia glutinosa and Ruscus aculeatus (see above). Fluctuations may occur with immunological symptoms (fluctuating fevers or glandular swelling, inflammatory symptoms such as joint pains and regional or diffuse muscle pain) require careful assessment. Exclusion of persistent infection through specific assessment for infectious agents and immunological disorders may be required. Exclusion of toxic exposure or persistent toxins such as heavy metals needs to be considered. In addition the possibility of detoxification disorders of the liver may be excluded through appropriate functional liver detoxification studies.

KEY POINTS

Bruce M., Carruthers A., Kumar J., De Meirleir K.L., et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: clinical working case definition, diagnostic and treatment protocols. J Chronic Fatigue. 2003;11(1):7-116.

Shomon M.J. Living well with chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia. New York: HarperCollins; 2004.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome: http://www.cdc.gov/cfs/cfsdiagnosisHCP.htm

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of chronic fatigue syndrome: http://www.cdc.gov/cfs/cfsdefinitionHCP.htm#conditions_exclude

3. Merck Manual definition of chronic fatigue syndrome: http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec22/ch334/ch334b.html

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention causes of chronic fatigue syndrome: http://www.cdc.gov/CFS/cfscauses.htm

5. Lane R.J., et al. Enterovirus related metabolic myopathy: a postviral fatigue syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(10):1382-1386.

6. Nicolson G.L., et al. Multiple co-infections (Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, human herpes virus-6) in blood of chronic fatigue syndrome patients: association with signs and symptoms. Apmis. 2003;111:557-566.

7. Endresen G.K. Mycoplasma blood infection in chronic fatigue and fibromyalgia syndromes. Rheumatol Int. 2003;23:211-215.

8. Koelle D.M., et al. Markers of viral infection in monozygotic twins discordant for chronic fatigue syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:518-525.

9. Gustaw K. Chronic fatigue syndrome following tick-borne diseases. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2003;37:1211-1221.

10. Maes M., et al. Increased serum IgA and IgM against LPS of enterobacteria in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS): indication for the involvement of gram-negative enterobacteria in the etiology of CFS and for the presence of an increased gut–intestinal permeability. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;99(1):237-240.

11. http://www.cdc.gov/CFS/cfscauses.htm.

12. Lloyd A.R., et al. Immunity and the pathophysiology of chronic fatigue syndrome. Ciba Found Symp. 1993;173:176-187. discussion 187–192

13. Lloyd A., et al. Cell-mediated immunity in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, healthy control subjects and patients with major depression. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;87(1):76-79.

14. Lorusso L., et al. Immunological aspects of chronic fatigue syndrome. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8(4):287-291.

15. Smith A.K., et al. Genetic evaluation of the serotonergic system in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(2):188-197.

16. Shephard R.J. Chronic fatigue syndrome: a brief review of functional disturbance and potential therapy. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 2005;45:381-392.

17. Griffith J.P., Zarrouf A.A. Systematic review of chronic fatigue syndrome: don’t assume it’s depression. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10(2):120-128.

18. Kuratsune H., et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate deficiency in chronic fatigue syndrome. Int J Mol Med. 1998;1(1):143-146.

19. Morriss R.K., et al. The relation of sleep difficulties to fatigue, mood and disability in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42(6):597-605.

20. Schondorf R., Freeman R. The importance of orthostatic intolerance in the chronic fatigue syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 1999;317(2):117-123.

21. Rowe P.C., Calkins H. Neurally mediated hypotension and chronic fatigue syndrome. Am J Med. 1998;28:105(3a):15s-21s.

22. Braun L., Cohen M. Herbs and natural supplements: an evidence based guide. Melbourne: Churchill Livingstone; 2007.

23. Lapp C..Using vitamin B12 for the management of CFS. CFIDS Chronicle. 1999(Nov/Dec):14-16.

24. Pall M.L. Cobalamin used in chronic fatigue syndrome therapy is a nitric oxide scavenger. J CFS. 2001;8(2):39-44.

25. Jacobson W., et al. Serum folate and chronic fatigue syndrome. Neurology. 1993;43(12):2645-2647.

26. Santaella M.L., et al. Comparison of oral nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) versus conventional therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome. P R Health Sci J. 2004;23(2):89-93.

27. Hempel S., et al. Risk factors for chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a systematic scoping review of multiple predictor studies. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:915-926.

28. Heim C., et al. Childhood trauma and risk for chronic fatigue syndrome: association with neuroendocrine dysfunction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(1):72-80.

29. Nater U.M., et al. Attenuated morning salivary cortisol concentrations in a population-based study of persons with chronic fatigue syndrome and well controls. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(3):703-709.

30. Rimes K.A., Calder T. Treatments for chronic fatigue syndrome. Occupational Medicine. 2005;55:32-39.

31. Sharpe M., et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy for the chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1996;312:22-26.

32. Whiting P., et al. Interventions for the treatment and management of chronic fatigue syndrome. A systematic review. JAMA. 2001;286(11):1360-1401.

33. Jones J.F., et al. Complementary and alternative medical therapy utilization by people with chronic fatiguing illnesses in the United States. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7:12.

34. Vernon H., Schneider M. Chiropractic management of myofascial trigger points and myofascial pain syndrome: a systematic review of the literature. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(1):14-24.

35. Murray M.E. Brain and CSF magnesium concentrations during magnesium deficit in animals and humans. Magnesium Res. 1992;5:303-313.

36. Cox I.M., et al. Red blood cell magnesium and chronic fatigue syndrome. Lancet. 1991;337:757-760.

37. Hart A.J., et al. Randomised controlled trial of Siberian ginseng for chronic fatigue. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:51-61.

38. Kulkarni S.K., Dhira A. Withania somnifera Indian ginseng. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2008;32(5):1093-1105.

39. Burgoyne B. Herbal treatment of insomnia. Modern Phytotherapist. 2002;7(1):12-21.

40. Larun L., et al. Exercise therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (3):2004. CD003200

41. Bone K. Chronic fatigue syndrome and its herbal treatment. Townsend Letter for Doctors and Patients. 1 November 2001.

42. Edmonds M., et al. Exercise therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2004. CD003200

43. Ruud C., et al. Exploratory open label, randomized study of acetyl- and propionylcarnitine in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:276-282.

44. Behan P.O., et al. Effect of high doses of essential fatty acids on the postviral fatigue syndrome. Acta Neurol Scand. 1990;82:209-216.

45. Regland B., et al. Nickel allergy is found in a majority of women with chronic fatigue syndrome and muscle pain—and may be triggered by cigarette smoke and dietary nickel intake. Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 2001;8(1):57-65.

46. Racciatti D., et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome following a toxic exposure. Sci Total Environ. 2001;270(1–3):27-31.

47. Morgan M., Bone K. Herbs to enhance energy and performance. In A phytotherapist’s perspective. Queensland: Mediherb; 2008. 124

48. Mishra L.C., et al. Scientific basis for the therapeutic use of Withania somnifera (ashwagandha): a review. Altern Med Rev. 2000;5(4):334-346.

49. Rhodiola rosea. Monograph. Altern Med Rev. 2002;7(5):421-423.

50. Redman D. Rusculus aculeatus (butcher’s broom) as a potential treatment for orthostatic hypotension with a case report. J Alt Compl Med. 2000;6(6):539-549.

51. PDRhealth. Online. Available: http://www.pdrhealth.com

52. Chen R, et al. Traditional Chinese medicine for chronic fatigue syndrome. eCAM, doi:10.1093/ecam/nen017.

53. Warren G., et al. The role of essential fatty acids in chronic fatigue syndrome: a case controlled study of red-cell membrane essential fatty acids (EFA) and a placebo-controlled treatment study with high dose of EFA. Acta Neurol Scand. 1999;99:112-116.

54. Graham, B. Associations between zinc/copper, metabolic rate and disability scales in chronic fatigue syndrome. Unpublished data, 2005. http://www.nutritional-healing.com

55. Tirelli U., et al. Immunological abnormalities in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Scand J Immunol. 1994;40(6):601-608.

56. Racciatti D., et al. Study of immune alterations in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome with different etiologies. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2004;17(2 Suppl):57-62.

57. Roth E. Immune and cell modulation by amino acids. Clin Nutr. 2007;26(5):535-544.

58. Leigh E. Echinacea—Green paper 2001. Boulder: Herb Research Foundation, 2001; Leigh E. Ginseng—Green paper 1997-2001. Boulder: Herb Research Foundation, 2001.

59. Hübner W.D., et al. Hypericum treatment of mild depressions with somatic symptoms. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1994;7(Suppl 1):S12-S14.

60. Price J.R., et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome in adults. Cochrane Database System Reviews. (3):2008. CD001027

61. Chambers D., et al. Interventions for the treatment, management and rehabilitation of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: an updated systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2006;99:506-520.

62. Deale A., et al. Cognitive behavior therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:408-414.

63. Prins J., et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;357:841-847.

64. Fulcher K.Y., White P.D. Randomised controlled trial of graded exercise in patients with the chronic fatigue syndrome. BMJ. 1997;314:1647-1652.

65. Powell P., et al. Randomised controlled trial of patient education to encourage graded exercise in chronic fatigue syndrome. BMJ. 2001;322:387-392.

66. Wearden A.J., et al. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled treatment trial of fluoxetine and graded exercise for chronic fatigue syndrome. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:485-492.

67. Behan W.M., Horrobin D. Effect of high doses of essential fatty acids on the postviral fatigue syndrome. Acta Neurol Scand. 1990;82:209-216.

68. Forsyth L.M., et al. Therapeutic effects of oral NADH on the symptoms of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1999;82:185-191.

69. Weatherley-Jones E., et al. A randomised, controlled, triple-blind trial of the efficacy of homeopathic treatment for chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;56(2):189-197.

70. Field T.M., et al. Massage therapy effects on depression and somatic symptoms in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 1997;3:43-51.