Chapter 115 Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Diagnosis

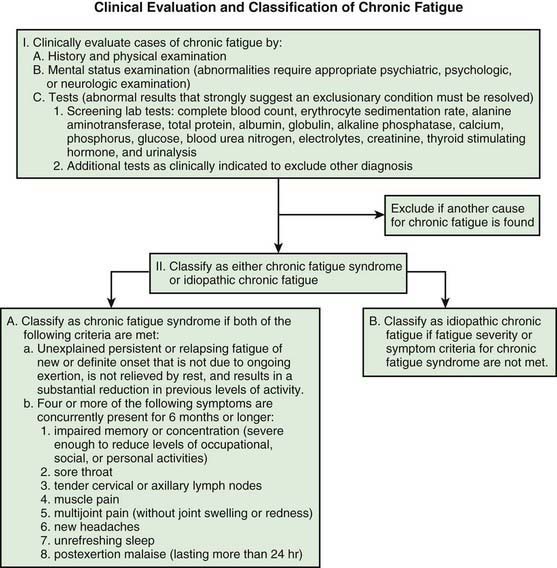

There are no pathognomonic signs or diagnostic tests for CFS. The diagnosis is a clinically defined condition based on inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 115-1). The diagnostic criteria are applicable to adults and adolescents >11 yr of age because of the current requirement for a self-generated history. Reliance on parental history for diagnosis is fraught with confusion because of the inaccuracy of the historical information. An empiric definition has been tested in adults that enhances diagnostic reliability. The process relies on results of 3 readily available questionnaires: Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory, Medical Outcomes Short Form 36, and CDC Symptom Inventory.

Fibromyalgia is a relatively common rheumatic syndrome characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain in addition to numerous specific tender point sites (Chapter 162) and symptoms similar to those of CFS. Fibromyalgia and CFS may be diagnosed in the same patient since both are diagnoses by definition and both lack confirmatory laboratory findings.

Although evaluation of each patient should be individualized, initial laboratory evaluation should be limited to screening laboratory tests to provide reassurance of the lack of significant organic dysfunction (see Fig. 115-1). Further tests should be directed primarily toward excluding treatable diseases that may be suggested by the symptoms or physical findings that are present in specific patients. Diagnostic evaluation of chronic fatigue should include psychologic evaluation for anxiety and depression disorders, which should precede exhaustive searches for organic causes.

Cameron B, Bharadwaj M, Burrows J, et al. Prolonged illness after infectious mononucleosis is associated with altered immunity but not with increased viral load. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:664-671.

Capuron L, Welberg L, Heim C, et al. Cognitive dysfunction relates to subjective report of mental fatigue in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1777-1784.

Chalder T, Deary V, Husain K, et al. Family-focused cognitive behavior therapy versus psycho-education for chronic fatigue syndrome in 11- to 18-year-olds: a randomized controlled treatment trial. Psychol Med. 2009 Nov;6:1-11. (Epub ahead of print)

Chambers D, Bagnall AM, Hempel S, et al. Interventions in the treatment, management and rehabilitation of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: an updated systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2006;99:506-520.

Crawley E, Davey Smith G. Is chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS/ME) heritable in children, and if so, why does it matter? Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:1058-1061.

Davies S, Crawley E. Chronic fatigue syndrome in children aged 11 years old and younger. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:419-421.

Elena Garralda M, Chalder T. Practitioner Review: chronic fatigue syndrome in childhood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:1143-1151.

Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, et al. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:953-959.

Godfrey E, Cleare A, Coddington A, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome in adolescents: do parental expectations of their child’s intellectual ability match the child’s ability? J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:165-168.

Gordon B, Lubitz L. Promising outcomes of an adolescent chronic fatigue syndrome inpatient programme. J Paediatr Child Health. 2009;45:286-290.

Heim C, Nater UM, Maloney E, et al. Childhood trauma and risk for chronic fatigue syndrome: association with neuroendocrine dysfunction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:72-80.

Katz BZ, Shiraishi Y, Mears CJ, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome after infectious mononucleosis in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2009;124:189-193.

Lombardi VC, Ruscetti FW, Das Dupta J, et al. Detection of an infectious retrovirus, XMRV, in blood cells of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Science. 2009;326:585-589.

Prins JB, van der Meer JW, Bleijenberg G. Chronic fatigue syndrome. Lancet. 2006;367:346-355.

ter Wolbeek M, van Doornen LJ, Kavelaars A, et al. Severe fatigue in adolescents: a common phenomenon? Pediatrics. 2006;117:e1078-e1086.

Wagner D, Nisenbaum R, Heim C, et al. Psychometric properties of the CDC symptom inventory for the assessment of chronic fatigue syndrome. Popul Health Metr. 2005;3:8.

White PD, Thomas JM, Sullivan PF, et al. The nosology of sub-acute and chronic fatigue syndromes that follow infectious mononucleosis. Psychol Med. 2004;34:499-507.

Whiting P, Bagnall AM, Sowden AJ, et al. Interventions for the treatment and management of chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic review. JAMA. 2001;286:1360-1368.