7 Chronic Diffuse Lung Diseases

Diffuse or “interstitial” lung diseases (ILDs) include a spectrum of primarily non-neoplastic inflammatory conditions that share the common property of diffuse involvement of the lung parenchyma. The term “ILD” has become so thoroughly entrenched across multiple medical disciplines that it seems practical to continue its usage, although we would emphasize that many of the diseases discussed in this chapter also involve the alveolar spaces and terminal bronchioles to a variable extent and would therefore not be considered entirely “interstitial” by the anatomic purist.1

This chapter focuses on the subacute and chronic forms of ILD (acute ILDs are discussed in Chapter 5), which includes diseases that typically evolve over weeks, months, or years. Patients with ILD share a number of clinical and radiologic manifestations, including: (1) shortness of breath (dyspnea), (2) diffuse abnormalities in lung mechanics and gas transfer (pulmonary function), and (3) diffuse abnormalities on chest radiographs and computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest.2

An overview of ILD from the pathologist’s perspective is presented in Box 7-1. In this chapter we will restrict our focus to a limited number of predominantly inflammatory diseases that come to biopsy relatively frequently (Box 7-2). Our emphasis is on the histopathologic patterns of these diseases as observed through the microscope. These patterns help narrow the differential diagnosis and often allow for a definitive diagnosis when coupled with clinical and radiologic data.

Box 7-1 Overview of the Chronic Diffuse Interstitial Lung Diseases

COP, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia; DIP, desquamative interstitial pneumonia; LIP, lymphoid interstitial pneumonia; NSIP, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; RBILD, respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

Box 7-2 Chronic Interstitial Lung Diseases Presented in This Chapter

COP, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia; DIP, desquamative interstitial pneumonia; LIP, lymphoid interstitial pneumonia; NSIP, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; RBILD, respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

Unlike neoplasms, which may have distinctive or even unique morphologic features, ILDs are distinguished from one another by (1) location involved (anatomic compartment or structure), (2) distribution (focal or diffuse), and (3) cellular composition (e.g., acute, chronic, histiocytic) of the inflammatory reaction. Additional identification criteria include the mechanism by which repair is taking place (organizing or not) and the stage of the reparative process (acute: fibroblastic proliferation; subacute: fibroblasts accompanied by matrix and epithelial regeneration; chronic: dense fibrosis and structural remodeling).2

Transbronchial and surgical wedge biopsy interpretation in the ILD patient is complicated by several factors.3 First, these diseases involve the interstitium, but they are frequently attended by reactive changes in the surrounding alveolar spaces and associated terminal airways. Such reactive changes can be quite impressive and commonly distract the observer from recognizing the interstitial nature of the process. Second, the inherent variability and natural history of inflammatory diseases pose problems, wherein early phases of a disease may differ in appearance from later phases, and the intensity of a reaction may vary from individual to individual. Third, more than one inflammatory disease can involve the lung simultaneously, adding further complexity to the morphologic picture. Finally, and perhaps of greatest importance, these predominantly medical diseases cannot be diagnosed accurately without some clinical and radiologic correlation.4

One of the most important chronic lung diseases in pulmonary medicine today is known clinically as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). This most devastating of chronic ILDs is often the diagnosis of exclusion from a clinical perspective and one against which all other chronic lung diseases are judged. The reason for this is that IPF is a disease that progresses despite therapy and rivals many cancers in mortality rate, with death often occurring within 3 years of the diagnosis.5 As emphasized in the 2002 joint consensus statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), the pathologic manifestation of IPF in the lung is usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP).6 UIP was a term introduced by Liebow in reference to one of five forms of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP).7 In Liebow’s words, UIP represents “chronic lung fibrosis of the common or usual type,”—a seemingly broad category of chronic lung disease.

Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias

Liebow’s initial classification of IIPs is presented for historical purposes in Box 7-3. In the years following the introduction of this classification scheme, new information led to the modification or elimination of certain of these IIPs and the addition of others not previously included8,9 (Box 7-4). Since Liebow’s time, it has been established that desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP), initially thought to be an early manifestation of UIP,10 is in fact a smoking-related disease in a majority of cases, most often affecting adults.11,12 Subsequent investigation also showed that giant cell interstitial pneumonia (GIP) was actually a manifestation of cobalt exposure, as a pneumoconiosis in “hard metal disease” (see Chapter 8).13 Finally, it became apparent that many early cases of lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP) evolved into lymphoproliferative disease and probably did not constitute “inflammatory” disease in the true sense of the word.bb0080 bb0085

Box 7-3 Historical Classification of Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias

Data from Liebow A, Carrington C: The interstitial pneumonias. In: Simon M, Potchen EJ, LeMay M, eds. Frontiers of Pulmonary Radiology: Pathophysiologic, Roentgenographic and Radioisotopic Considerations. Orlando, FL: Grune & Stratton; 1969:109–142.

Box 7-4 Initial Revised Classification of Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias

Reprinted with permission from Katzenstein A, Askin F, eds. Surgical Pathology of Non-Neoplastic Lung Disease, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990:49, Table 3-1.

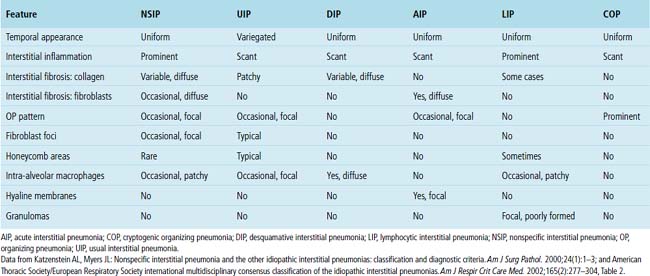

Based on this evolution in our understanding, a modification to Liebow’s original classification of the IIPs was proposed by Katzenstein.8,9 This new schema included the major categories of UIP and DIP but coupled DIP with “respiratory bronchiolitis–associated interstitial lung disease” (RBILD) and acknowledged the strong relationship of these diseases to cigarette smoking. Katzenstein also proposed a new category of acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP)15 as an entity separate from UIP, a distinction that Liebow did not make in his initial classification. Finally, Katzenstein created a new category to encompass a group of inflammatory diseases that differed in appearance from UIP, DIP, or AIP. The term nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) was proposed for this “new” pattern.16 In our experience, a majority of IIPs can be classified using this scheme. We would add idiopathic (cryptogenic) organizing pneumonia, previously known as “idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia,”17 to this classification, as has been recommended by the 2002 International Workshop on the classification of IIPs.6 That workshop retained LIP in the classification (Table 7-1), acknowledging the presence of some morphologic overlap with NSIP once a lymphoproliferative disease has been excluded by all available means. Importantly, the consensus panel determined that NSIP should be included in the IIPs as a provisional category until additional data accrue.6

Table 7-1 International Consensus Classification of Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias (2002)

| Histopathologic Pattern | Clinical-Radiologic-Pathologic Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Usual interstitial pneumonia | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis/cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis |

| Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia | Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (“provisional”) |

| Respiratory bronchiolitis | Respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease |

| Desquamative interstitial pneumonia | Desquamative interstitial pneumonia |

| Organizing pneumonia | Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia |

| Diffuse alveolar damage | Acute interstitial pneumonia |

| Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia | Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia |

Reprinted with permission from American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(2):277–304, Table 2.

IIPs are classically defined as diffuse pulmonary diseases that involve two or more lobes of the lung; in most patients, such diseases are bilateral in distribution.18 Some localized lesions (such as infection, atelectasis, or tumor) may mimic IIP in a biopsy specimen. It is safe to say that if a disease process is confined to the biopsy area sampled, it is unlikely to be an IIP. AIP is an acute form of IIP (discussed in detail in Chapter 5). A comparison of the histopathologic findings in each of the IIPs is presented in Table 7-2. The importance of accurately diagnosing these IIPs lies mainly with differences in prognosis. UIP is a uniformly fatal disease for which the median survival period historically is less than 3 years in its classic presentation (CT with honeycombing), competing with many cancers in this respect.

Usual Interstitial Pneumonia

Pulmonary pathologists have debated for years what is, and what is not, UIP. To some, UIP is a relatively nonspecific pattern of chronic lung injury with fibrosis and “honeycomb” remodeling (see further on). Today it is recognized that not all lung diseases with fibrosis behave similarly and, in particular, do not run the aggressive course expected for clinical IPF. The most honest answer may be that clinical and radiologic IPF has UIP-type pathologic changes, but that a UIP pattern of parenchymal fibrosis with remodeling may be seen in biopsy specimens and may not necessarily correlate with clinical and radiologic IPF. Fortunately, not all lung diseases that produce scarring fit the pattern now defined as UIP. Asbestosis,19–21 chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis,22–24 systemic collagen vascular diseases (CVDs),25–28 and even some chronic toxic drug reactions29 can all produce lung fibrosis. Unfortunately, in the 30 years following Liebow’s introduction of UIP as an “idiopathic” interstitial disease, pathologists often used the designation of UIP in a variety of nonidiopathic settings (e.g., “UIP from asbestosis” or “UIP from rheumatoid arthritis”). If UIP is defined as simply any form of lung fibrosis, then applying UIP as a synonym for fibrosis is perfectly reasonable. On the other hand, if UIP is a distinctive pathologic entity that corresponds to an idiopathic clinical disease (IPF), then UIP should have identifiable features that afford it status as a unique disease process. That there is a continued misconception of UIP among pathologists is underscored by feedback from our clinical colleagues, who note that many diagnoses of UIP provided by the pathology laboratory do not correspond to clinical IPF in their patients’ presentation, response to therapy, or observed outcome.

Clinical Presentation

The incidence of UIP varies by gender, with males predominating. The disease may have a prevalence in the United States as high as 43 per 100,000, using broad criteria30; roughly two thirds of patients are older than 60 years of age at diagnosis.5,31 For this reason, caution should be exercised when considering a diagnosis of UIP in patients who are younger than 50 years of age, and preferably expert consultation should be sought in this setting. Symptoms typically progress insidiously for months to years before diagnosis. The onset of a nonproductive cough and slowly progressive dyspnea are characteristic. Dry inspiratory crackles (so-called Velcro crackles) are detected at the lung bases on chest auscultation in more than 80% of patients at presentation.5 Clubbing of the digits is seen in 25% to 50% of patients at presentation. Fever is rare, and its presence should suggest an alternate diagnosis, as should a significantly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (greater than 100 mm/hour). Serologic studies such as antinuclear antibody (ANA) or rheumatoid factor (RF) assays may reveal mildly elevated titers, but when significant elevation is present, a systemic connective tissue disease should be strongly considered. Also, in patients presenting with clinical features of UIP or IPF in whom a defined CVD develops later, reclassification of their disease may be necessary.

Radiologic Findings

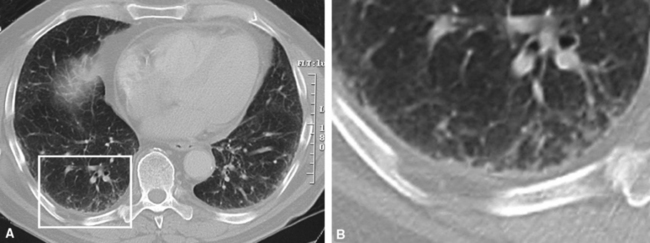

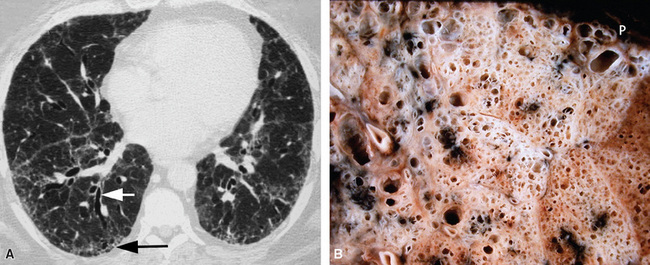

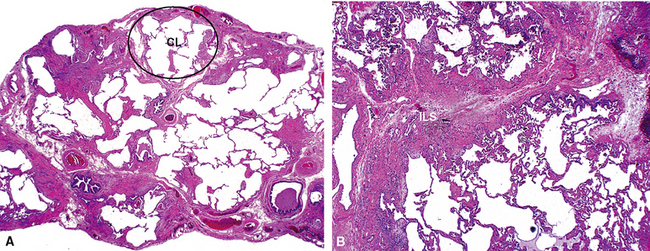

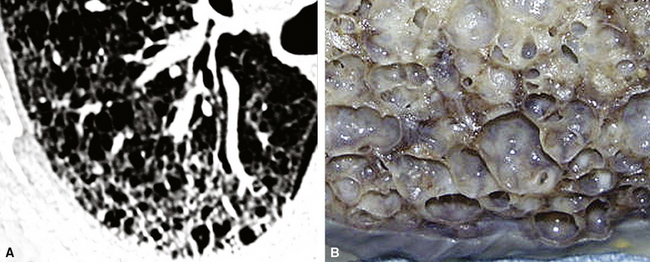

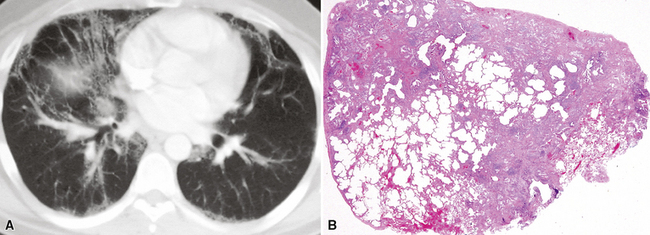

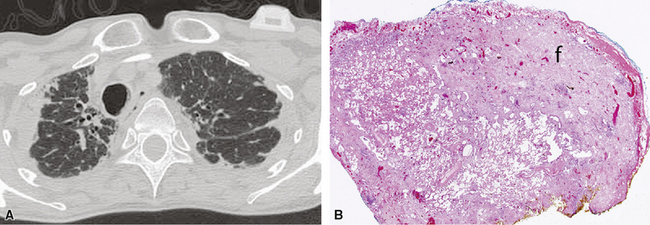

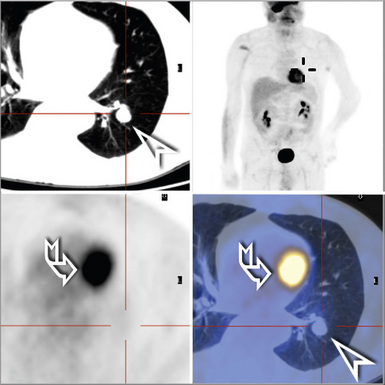

On chest radiographs, peripheral reticular opacities involving the lung bases are a characteristic finding.32 When present, these usually are bilateral and often asymmetrical. Lung volumes are typically decreased at presentation except in cases with severe upper lobe (centriacinar) emphysema.33 Unfortunately, a normal chest radiograph does not exclude the diagnosis.34 Confluent alveolar opacities are rare and, if present, suggest an alternate diagnosis or a comorbid process. CT scans, preferably of the high-resolution type (i.e., with scan sections ≤ 1 mm), commonly show patchy, predominantly peripheral (subpleural) reticular abnormalities involving the lung bases bilaterally.35 Some asymmetry is expected between right and left lungs, and characteristic “skip” areas are present, with coarse pleural-based reticulation alternating with adjacent better-preserved lung (so-called “radiologic heterogeneity”). The earliest findings may be quite subtle, consisting of delicate, peripherally accentuated pleural-based reticular opacities in the lower lung zones (Fig. 7-1). Ground-glass opacities are not typical and, if present, should be limited in extent.36–38 Subpleural cysts—ranging from a few millimeters to a centimeter or more in diameter (“radiologic honeycombing”)—increase in prominence as the disease advances (Fig. 7-2). In areas of more severe involvement, traction bronchiectasis often is evident. Diagnostic accuracy for IPF on high-resolution CT scan by trained observers is in the range of 90% when typical findings are present (high specificity); however, approximately one third of cases of UIP will be missed when relying on high-resolution CT diagnosis alone (low sensitivity).24,39

Histopathologic Findings

UIP cannot be diagnosed with the bronchoscopic or transbronchial biopsy specimen. Surgically derived wedge lung biopsies (3–5 cm in length by 2–3 cm in breadth), obtained from video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) or open thoracotomy, are the appropriate samples for diagnosis (see Chapter 2 for additional details on the lung biopsy). Occasionally, UIP will be evident in lobectomy and pneumonectomy specimens obtained for other diseases. UIP is a process that involves the periphery of the lung lobule; these areas are not sampled adequately in even the most ambitious transbronchial biopsy scenario (where many large fragments of alveolar parenchyma may be present, but are mainly derived from the central portion of the lung lobules). More than one biopsy site should be sampled, and preferably a biopsy sample should be obtained from all lobes in the hemithorax chosen for surgical intervention. If only two areas can be sampled, mid-lung and lower lung are preferable to upper and mid-lung, and samples from the lower lobe should be taken above the most advanced areas of fibrosis.

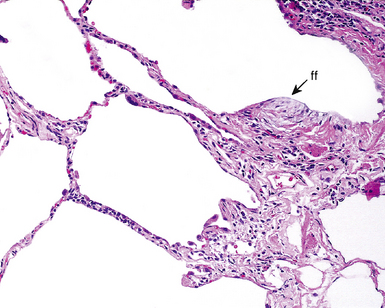

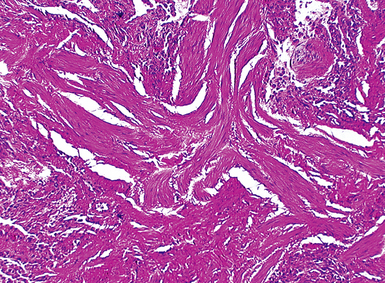

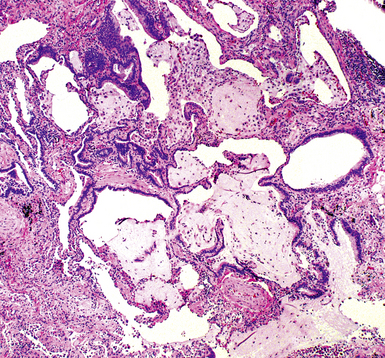

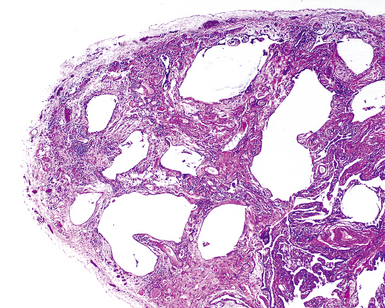

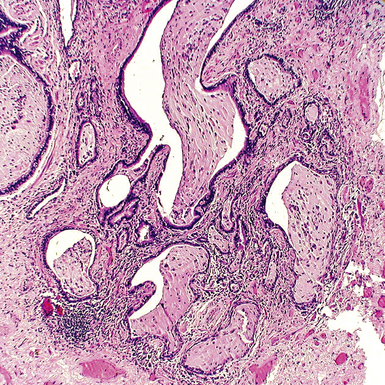

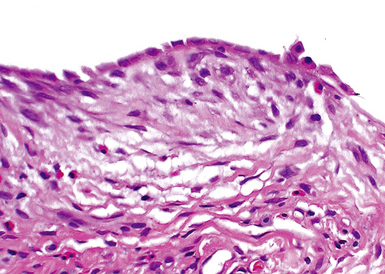

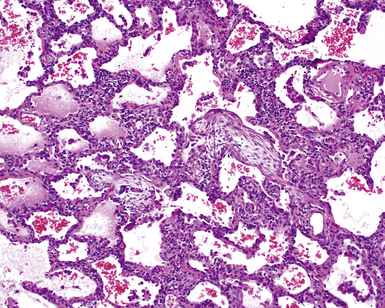

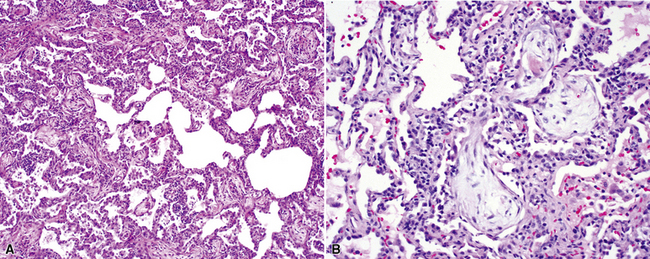

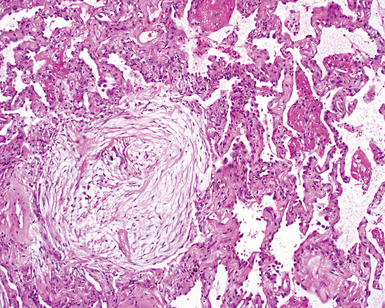

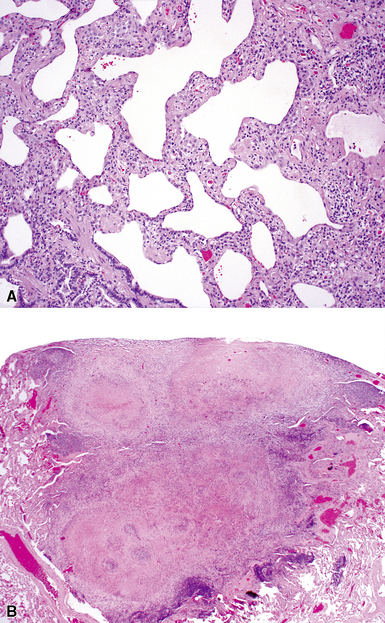

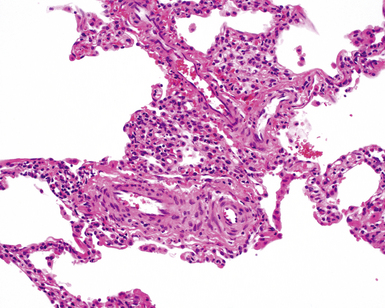

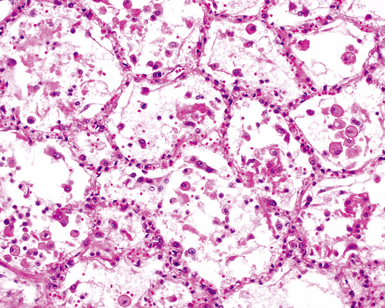

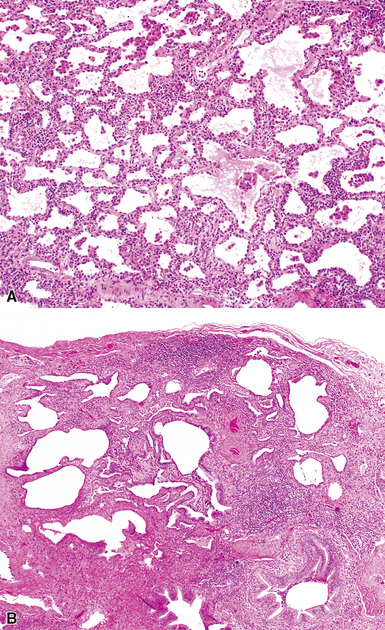

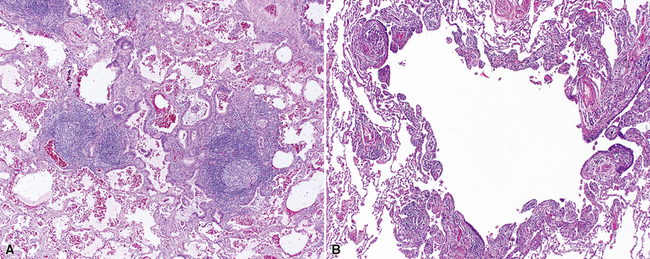

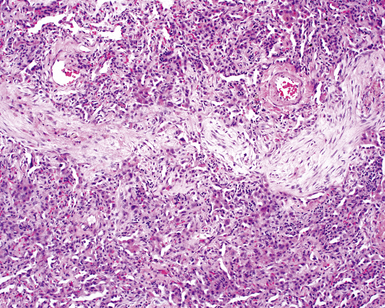

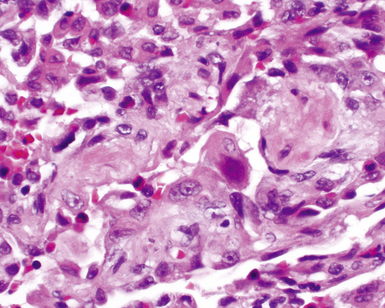

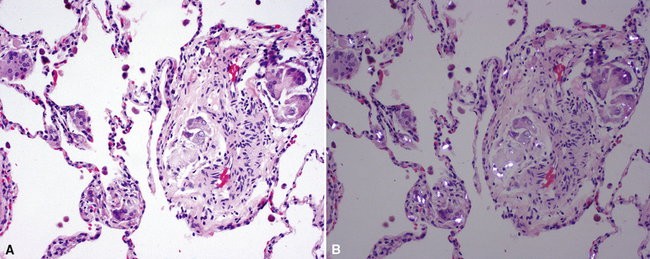

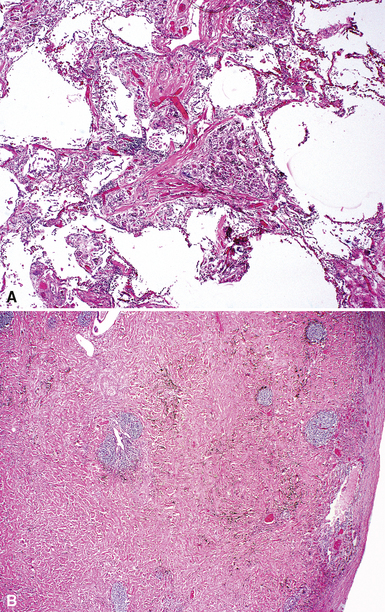

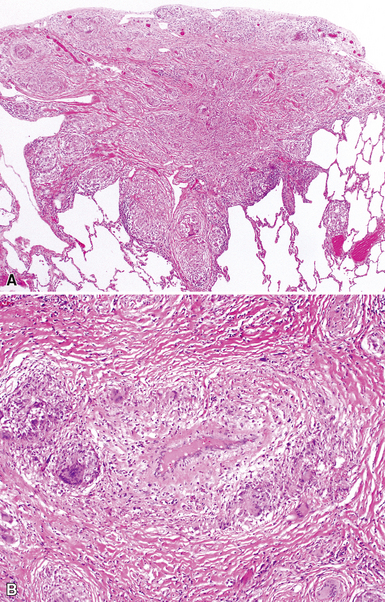

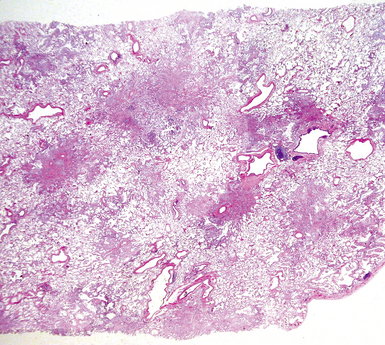

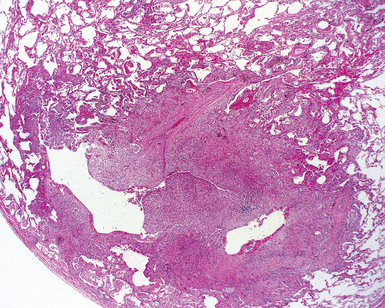

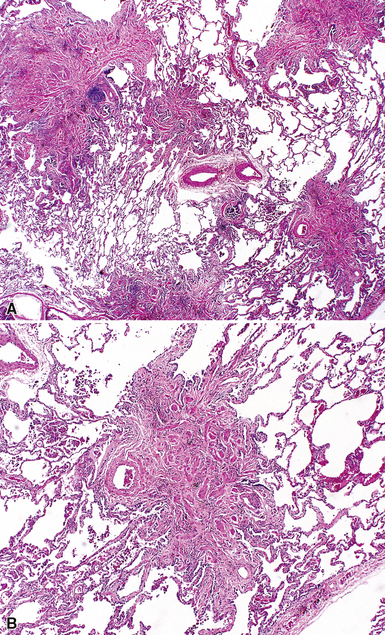

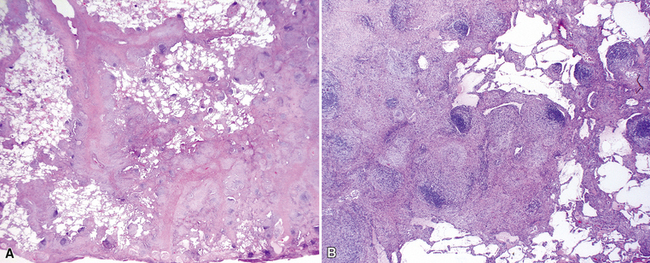

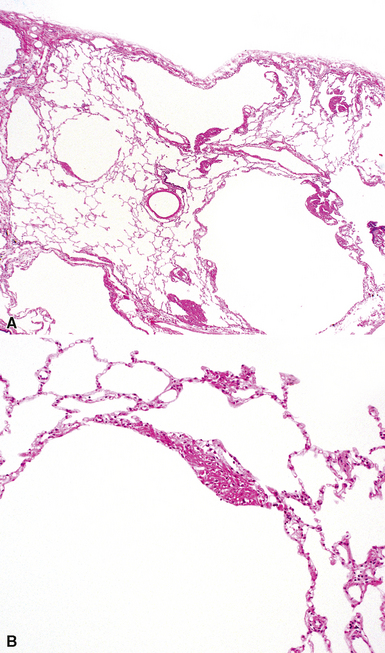

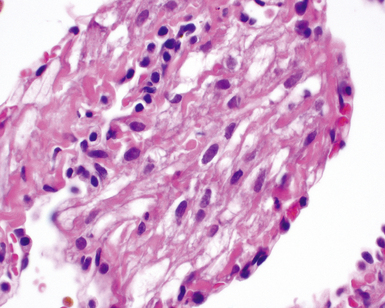

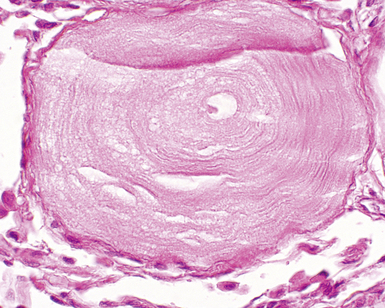

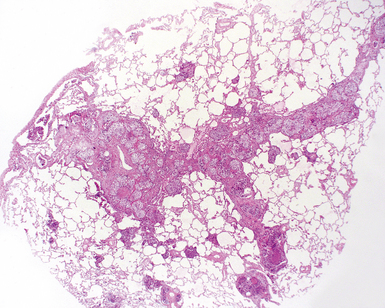

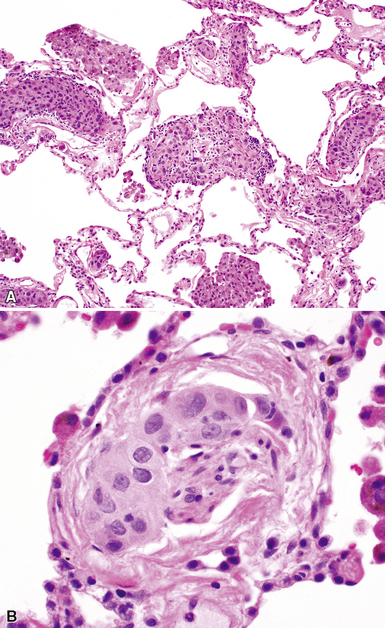

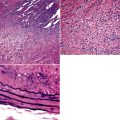

The characteristic histopathologic findings of UIP have been referred to as being “temporally heterogeneous” or having a “patchwork quilt” appearance,32,40–43 concepts and terms that are often misunderstood by surgical pathologists and pulmonologists. An expanded description of “temporal heterogeneity” is that of transitions in the biopsy from dense scar (the “past”) to normal lung (the “future”—lung tissue yet to be involved). At the juncture of these, transitions occur through patches of active lung injury referred to as “fibroblast” or “fibroblastic” foci (Fig. 7-3). The remodeled lung is present mainly beneath the pleura and at the periphery of the secondary lobule, adjacent to interlobular septa (Fig. 7-4). When UIP is recognizable as a distinct pathologic entity, the pleural fibrosis contains smooth muscle proliferation in disorganized fascicles (Fig. 7-5) and foci of microscopic honeycombing are evident, even when the overall process appears to be mild or early in its evolution (Fig. 7-6). Microscopic honeycombing probably represents one of the early manifestations of the gross honeycomb cysts seen in the end-stage of UIP. As used by radiologists, the term honeycombing refers to an array of much larger cysts (in the range of 0.5–3 cm or larger) as a localized manifestation of advanced lung remodeling (Fig. 7-7). Microscopic honeycomb cysts are considerably smaller (in the range of 1–3 mm) and typically are present subpleurally (Fig. 7-8). The cysts are lined by columnar ciliated epithelium and typically are filled with mucus, with variable amounts of acute inflammation and inflammatory debris (Fig. 7-9). When dense chronic inflammation is present in UIP, it is seen around these localized inflammatory lesions.

Between the two temporal extremes of “old” peripheral fibrosis and uninvolved lung present centrally in the lobule is the presumed active zone of injury in UIP, evidenced by a crescent-shaped bulge of immature fibroblasts (technically, myofibroblasts) and ground substance (see Fig. 7-3). This lesion is known as the fibroblastic focus and typically is not extensive in the biopsy. Fibroblast foci have been shown to be continuous linear structures in three-dimensional reconstruction.44 Some investigators have postulated that the increased number of these foci in a given UIP patient’s biopsy is associated with a worse prognosis, and that a relative lack of fibroblastic foci may be an explanation for the better prognosis observed for patients with UIP-like lung fibrosis related to systemic CVDs.45

UIP is not an overtly inflammatory condition, in the absence of so-called acute exacerbation (see further on). This is not to imply that fibrosis occurs “mysteriously” in the disease. Some form of injury is occurring in UIP, but it seems to be subtle and probably is directed at the alveolar epithelium and its underlying basement membrane (epithelial-mesenchymal transitions). The fibroblastic foci of UIP appear immediately beneath reactive-appearing alveolar lining epithelium, where they obscure the epithelial basement membrane and bulge into the adjacent air space (Fig. 7-10), as though they were aborted “Masson polyps” of the type seen in organizing pneumonia (see later under “Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia”). Further evidence of an injury repair phenotype for UIP/IPF is the consistent presence of reactive type II cell proliferation overlying fibroblastic foci. Conceptually, the subtle inflammatory disease of UIP burns like a smoldering fire through the lung, leaving fibrosis, smooth muscle proliferation, microscopic honeycombing, and fibrosis in its path.

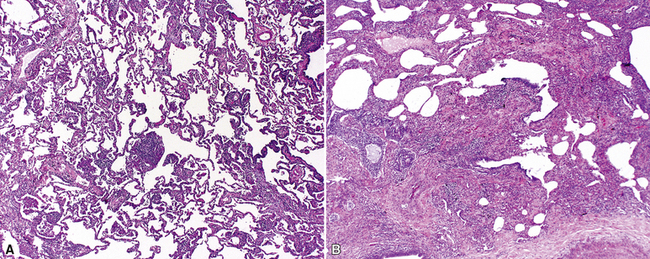

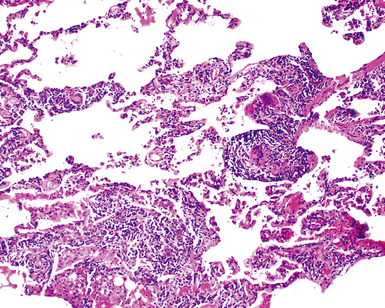

Acute Exacerbation

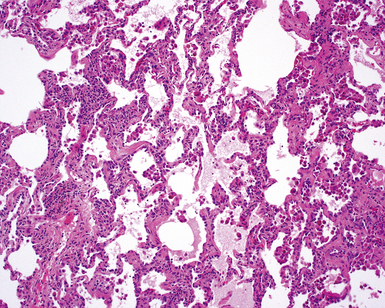

In his writings, Liebow conceived of UIP as a chronic lung disease resulting from repeated subclinical episodes of “diffuse alveolar damage” (DAD).7 In support of this hypothesis, episodic deterioration is typical in patients with IPF.5 In some patients with IPF, however, clinical deterioration is abrupt and overwhelming. Many of these acute deteriorations are of unidentifiable cause and have been referred to as “acute exacerbations of IPF.” Acute exacerbations have been the subject of considerable laboratory investigation, but the mechanism of their occurrence remains unknown. We do know that when such episodes are biopsied, the most consistent pathologic finding is that of DAD.46 Acute exacerbations of IPF can manifest as other patterns of acute lung injury, such as organizing pneumonia, and despite the implication of the term, the “acute” exacerbation tends to evolve over several weeks, rather than a few days.47 The mixed histopathologic changes can be confusing to the surgical pathologist examining the lung biopsy (and to the radiologist) because the background older fibrosis with microscopic honeycombing of UIP is often overshadowed by diffuse acute lung injury (Fig. 7-11).

The three patients described by Kondoh and coworkers all showed some degree of improvement in the short term after high-dose corticosteroid therapy, but no consistently effective therapy has emerged.46 Several investigators have proposed that acute exacerbations may be the common terminal episode in many patients with IPF, even though respiratory failure has always been presumed to be of slower evolution.48 Based on all available data, including data from the placebo arms of several large randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in patients with IPF, an estimated 10% to 15% of patients with UIP experience overwhelming acute exacerbation during the course of their disease, and this is often the fatal event for those affected.47,49

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for the UIP pattern includes a number of diseases that produce lung fibrosis. When this is a diffuse bilateral process, the main entities in the differential diagnosis are listed in Box 7-5. There are cases showing coexistence of histopathologic patterns of NSIP and UIP in the same patient in multiple lobe biopsies.50 Such cases can be considered “discordant” UIP.51 The clinical course of discordant UIP is still more like that of “non-discordant” UIP, however, with possibly longer survival.52

Clinical Course

The most common causes of death among patients with IPF are listed in Box 7-6. As defined clinically, IPF patients have a median survival time of less than 3 years.53 At present, no effective therapy has been established for IPF, but newer therapies are on the horizon using human recombinant cytokines as agents antagonistic to the effects of potentially “responsible” molecules.

Box 7-6 Cause of Death in 543 Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis*

Data from Panos RJ, Mortenson RL, Niccoli SA, King TE Jr: Clinical deterioration in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: causes and assessment. Am J Med. 1990;88(4):396–404.

A number of therapeutic approaches have been attempted in clinical trials. These include use of human recombinant interferon γ-1β, the antifibrotic compound pirfenidone, the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine, and several endothelin receptor antagonists (e.g., bosentan, ambrisentan). To date, no trial has revealed a successful cure for the disease. However, perfenidone has emerged as a candidate for slowing functional loss in IPF patients and is approved for the treatment of IPF in Japan.54,55

Essential Requirements for Accurate Diagnosis

For pulmonary physicians, a pathologic diagnosis of UIP implies clinical IPF; accordingly, UIP should never be diagnosed in the absence of clinical and radiologic correlation. The gravity of the prognosis and the lack of current available therapy strongly support this notion.5 If the pathologic findings are compelling for a UIP pattern, it is reasonable to use a descriptive diagnosis such as that presented in Box 7-7. This approach provides an opportunity for further correlation by clinical colleagues and radiologists in solidifying the diagnosis.

Data from Leslie K, Colby T, Swensen S: Anatomic distribution and histopathologic patterns in interstitial lung disease. In: Schwarz M, King TJ, eds. Interstitial Lung Disease. Hamilton, ON: BC Decker; 2002:31–50; and American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(2):277–304.

Familial Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

There is a small subset of patients with IPF who have a history of unexplained lung disease in first-degree relatives. This form of pulmonary fibrosis has been referred to as familial IPF or familial interstitial pneumonia (although in most studies of familial interstitial pneumonia, fibrosis seems to be the dominant pattern of disease). A compelling body of evidence suggests that IPF is a genetic disorder,56,57 and its familial occurrence is not surprising. Steele and colleagues examined the population of persons with familial interstitial pneumonia from 111 candidate families and found that more than 80% of these individuals had clinical IPF, followed by NSIP.58 Genetic analysis was performed in search of the mechanism underlying familial IPF, and telomerase germ line mutations were identified in 8%.59 The role of telomerase mutations was hypothesized to be a function of excess telomere shortening over time, resulting in cellular dysfunction and premature cell death.

Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonia

For many years after Liebow’s classification of IIPs was widely adopted, a number of diffuse inflammatory lung diseases were identified that did not fit well within this classification scheme. Various terms were applied to such diffuse lung diseases, including “chronic cellular” and “unclassifiable” interstitial pneumonia.60 In 1994 the term nonspecific interstitial pneumonia was proposed by Katzenstein and Fiorelli, based on data from 64 patients who presented with diffuse lung disease and a chief complaint of dyspnea, usually present for several months before evaluation.16 Radiologic studies showed bilateral interstitial infiltrates with variable consolidation. Importantly, the 64 patients in this study had a significantly better prognosis than that observed for patients with UIP.

Katzenstein and Fiorelli recognized that the constellation of histopathologic patterns seen in NSIP did not represent one disease and, in follow-up investigations, found that these patients often had hypersensitivity, resolving infection, or systemic CVD, among other occurrences. Nagai and coworkers studied a group of patients with cellular interstitial pneumonia and rigorously excluded possible etiologies. The reported survival rate in this “idiopathic NSIP” was 90% at 5 years.61 Thus, when used in the true idiopathic context, the designation “NSIP” may actually be useful if it consistently implies an interstitial chronic inflammatory disease of unknown etiology, with an expected good response to therapy and excellent survival rate. If, on the other hand, the term is applied indiscriminately as a substitute for any histopathologically unrecognized ILD, clinical behavior will be impossible to predict, thereby significantly reducing the benefit of lung biopsy.

Clinical Presentation

Some general statements can be made regarding the clinical presentation in NSIP, recognizing that most of the available data have been derived from studies in which a heterogeneous group of disorders were represented. Patients with NSIP histopathology in lung biopsies (that is, an NSIP pattern) tend to be younger than patients with UIP61–63; the NSIP pattern might also appear in children.16 As with many of the chronic diffuse lung diseases, symptoms develop gradually. Shortness of breath, cough, fatigue, and weight loss are the most common complaints. Fever and digital clubbing have been reported but are uncommon.16,62

Radiologic Findings

As in UIP, most of the chest x-ray abnormalities in NSIP are confined to the lower lung zones and tend to be bilateral and symmetrical.64 Less than 40% of the lung volume is typically involved. Patchy parenchymal (alveolar) opacification is a commonly reported abnormality,64 but reticular (interstitial) changes have also been identified.16 High-resolution CT findings are variable and nonspecific.65 The most common findings are a reticular pattern and traction bronchiectasis, followed by lobar volume loss and ground-glass attenuation. As uncommon features, subpleural sparing, irregular linear opacities, patchy honeycombing, and nodular opacities can be seen.61,62 As might be anticipated, some of the findings described for NSIP overlap with those in other ILDs, such as hypersensitivity pneumonitis and COP. In the stage before honeycomb cysts are visible, even UIP can be indistinguishable from NSIP.

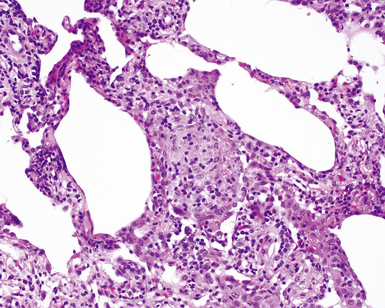

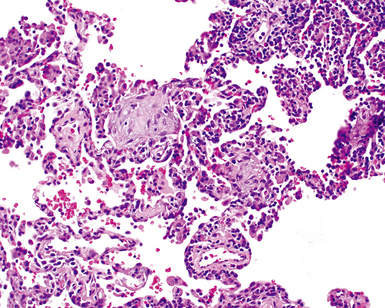

Histopathologic Findings

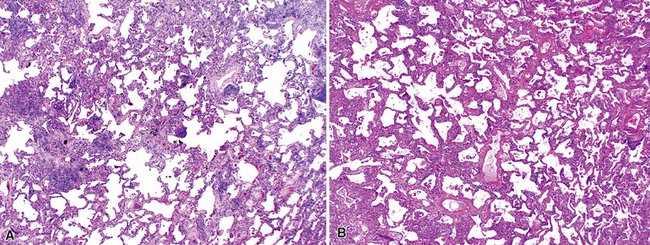

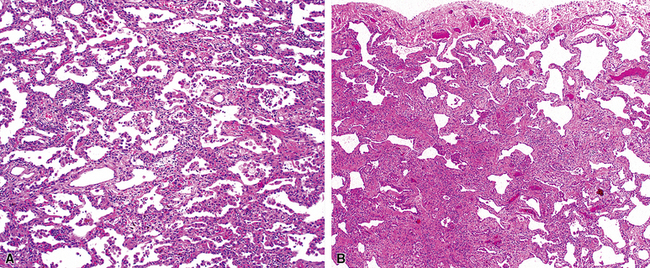

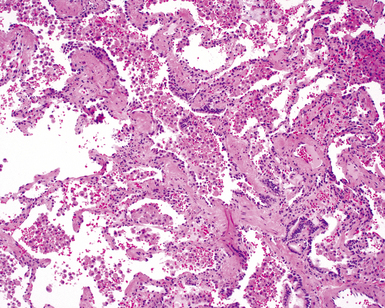

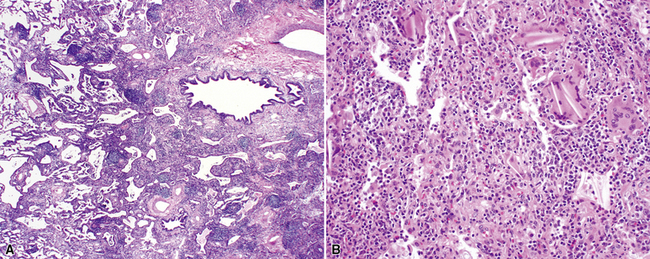

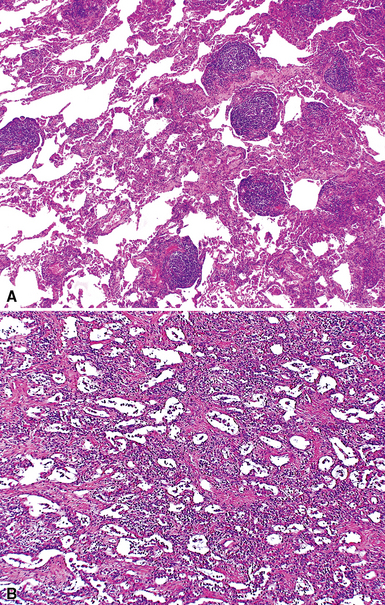

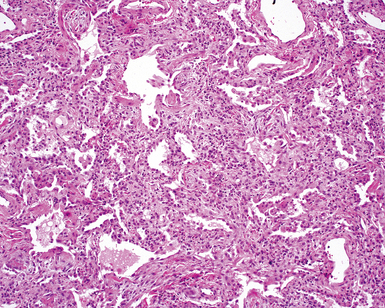

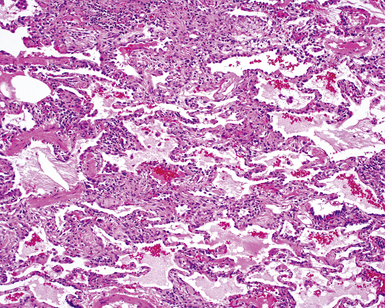

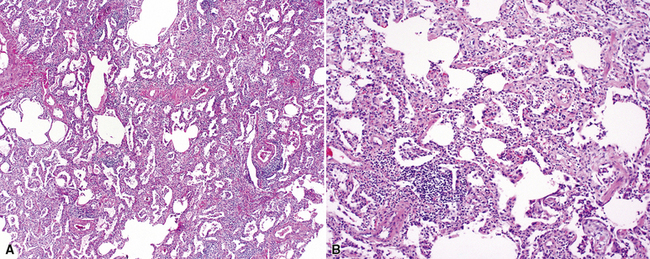

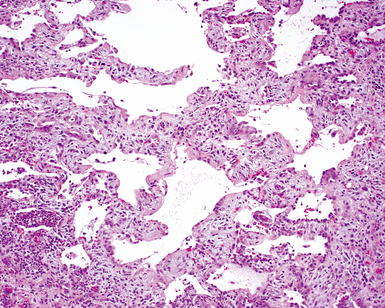

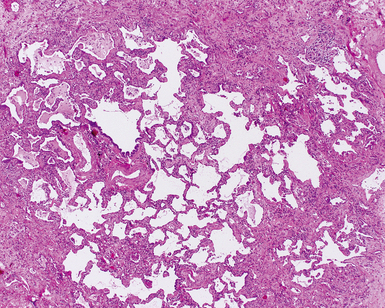

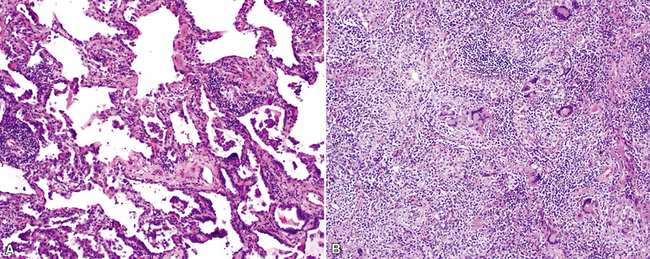

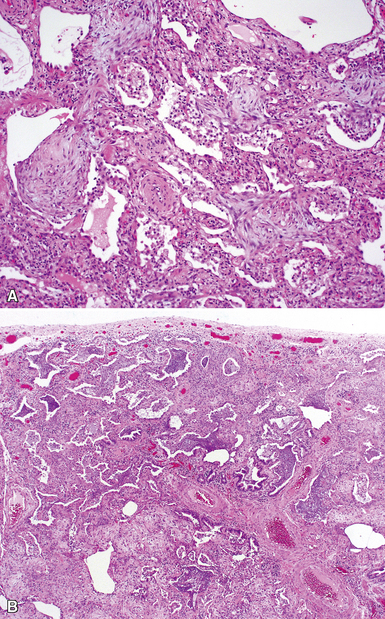

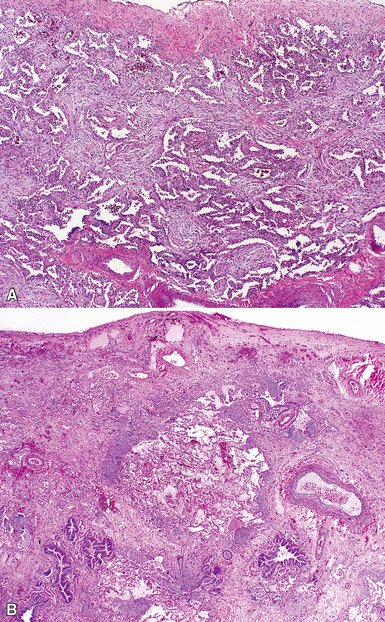

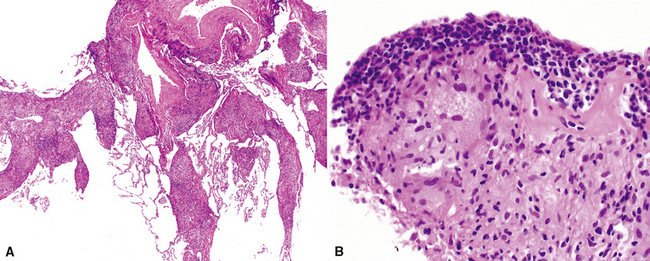

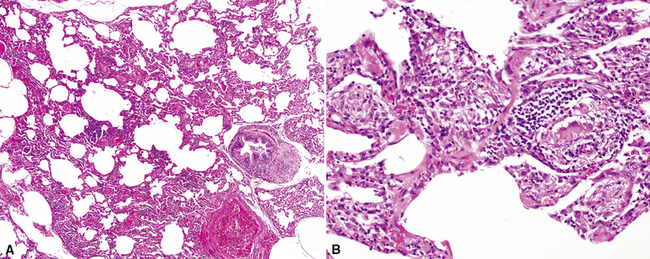

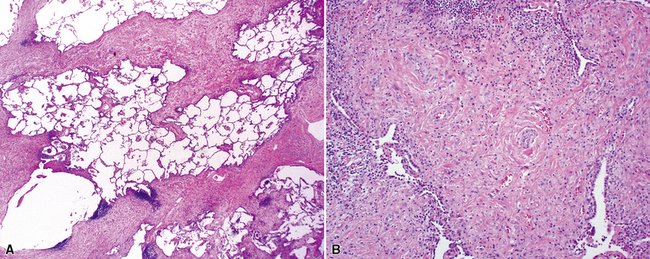

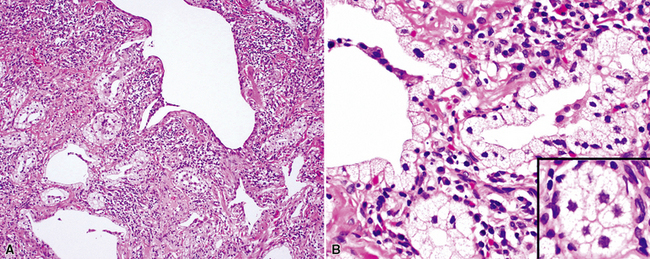

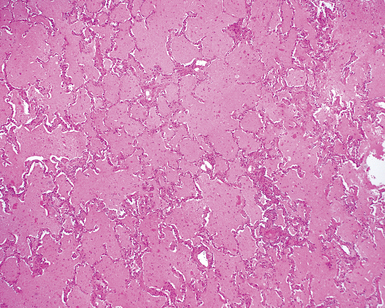

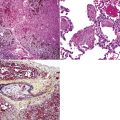

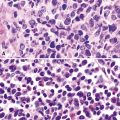

Katzenstein and Fiorelli emphasized that the histopathologic pattern in NSIP was temporally uniform (Fig. 7-12), in contrast with the UIP pattern, in which variable zones of established (dense) fibrosis, more active fibroplasia, and normal lung all coexist in the same biopsy specimen (i.e., temporal heterogeneity). As initially defined, the inflammatory process in NSIP is diffuse and uniform, mainly involving the alveolar walls (Fig. 7-13) and variably affecting the bronchovascular sheaths (Fig. 7-14) and pleura16 (Fig. 7-15). In some patients, infiltrates are predominantly peribronchial, whereas in others, germinal centers may be seen along with chronic pleuritis. When air space organization (the organizing pneumonia pattern) is present, it is not uniformly distributed (Fig. 7-16) as might occur in organizing infectious pneumonia.16 When fibrosis occurs in NSIP, it is usually mild and preserves lung structure (Fig. 7-17). Peribronchiolar metaplasia of variable extent may be seen, but microscopic honeycombing is characteristically absent.16,66

There has been debate as to whether NSIP is a new “interstitial lung disease” or simply a wastebasket category of diseases with some overlapping features. An American Thoracic Society project concluded that idiopathic NSIP is likely a distinct clinical entity with characteristic radiologic and pathologic features.66 Caution is advised in using this term for any lung disease with interstitial inflammation, just as it is imprudent to diagnose all fibrosing lung diseases as UIP.

Differential Diagnosis

The main entities in the differential diagnosis of the NSIP pattern include hypersensitivity pneumonitis, systemic CVDs manifesting in the lung, resolving infection, and low-grade lymphoproliferative disease masquerading as LIP (see later on). Cellular NSIP and LIP may be difficult to distinguish from one another on histopathologic grounds, so they might be considered synonymous from the pathologist’s perspective, once lymphoproliferative disease has been rigorously excluded. Kinder and associates hypothesized that a majority of NSIP cases fall into the category of undifferentiated connective tissue disease manifesting in the lung. Because of significant overlap between NSIP and ILD in CVD, careful follow-up with serologic testing is recommended.67 In clinical practice, in view of the limited arsenal of available therapies for ILD, managing NSIP as a systemic autoimmune disorder with immunosuppressive strategies (even though it may not be initially diagnosable by a rheumatologist) often proves to be the best course of action for the patient.

Clinical Course

The overall survival rate for patients with NSIP is estimated to be in the range of 82.3% at 5 years and 73.2% at 10 years.66 The purely “cellular” form of NSIP seems to be a disease with a good prognosis, compared with UIP and AIP.

When significant fibrous remodeling with microscopic honeycombing is permitted in the diagnosis of NSIP, 5- and 10-year survival rates change significantly for the worse.61,68 This observation suggests that fibrotic forms of NSIP may be within the spectrum of other fibrosing lung diseases, such as UIP of IPF, and certain systemic connective tissue diseases that manifest in the lung with fibrosis.

Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia

Air space organization is an extremely common manifestation of lung injury and can be seen after a wide variety of insults, from organizing lung infarction to bacterial pneumonia (Box 7-8). For this reason, the organizing pneumonia pattern in the lung biopsy is the least specific and perhaps the most misunderstood.

Box 7-8 Causes of the Organizing Pneumonia Pattern

Modified from Leslie K, Colby T, Swensen S: Anatomic distribution and histopathologic patterns in interstitial lung disease. In: Schwarz M, King TJ, eds. Interstitial Lung Disease. Hamilton, ON: BC Decker; 2002:31–50.

It is well known that lung repair following a wide spectrum of injuries frequently evolves through a phase of air space organization. When organization is diffuse, involving the entire surgical biopsy, organizing pneumonia (or “diffuse air space organization”) is an appropriate designation. When no etiology can be identified for an organizing pneumonia pattern, the clinical diagnosis of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) has been proposed (referred to previously as “idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia”).6,17,69

The term bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP), as an idiopathic disease, was first proposed by Davison and coworkers,69 and later used by Epler and associates,17 to define a specific clinical disease course in a group of patients in whom lung biopsies showed variable amounts of air space organization (organizing pneumonia pattern) of unexplained etiology. The importance of recognizing the pattern of organizing pneumonia in the clinical context defined relates to therapy and prognosis. Patients with clinical COP respond well to systemic corticosteroid administration, and pulmonologists expect a good prognosis when this diagnosis is implied histopathologically. When “BOOP” is used in a pathology report as a descriptive term for the occurrence of organizing pneumonia in a biopsy, the clinician may misinterpret this to mean “idiopathic BOOP” is the correct diagnosis. For example, the “BOOP” pattern may be seen in a disease with abundant background lung fibrosis. In this setting, the prognosis is best considered to be guarded.70

Clinical Presentation

As described by Epler and coworkers for the original “idiopathic BOOP,” the patient typically presents several weeks after an episode of clinical symptoms suggesting upper respiratory tract infection.17 The mean age at onset is 55 years, and a majority of patients are nonsmokers.71,72 Slowly worsening symptoms of cough (sometimes productive) and dyspnea are typically present, often leading to surgical lung biopsy within 3 months of disease onset. Weight loss, night sweats, chills, intermittent fever, and myalgias are common. Mild to moderate restrictive pulmonary function studies are identified in a majority of patients.72–74 Hemoptysis and wheezing typically are absent. Often there is a marked increase in the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Digital clubbing is not a feature of the disease.

Radiologic Findings

Chest radiography and CT show a number of abnormalities, none of which are specific for one disease. Patchy air space consolidation (loss of visible structure underlying opacification) is the most consistent finding and is present in 90% of cases.75,76 Air bronchograms can be seen in areas of consolidation. Ground-glass attenuation accompanies consolidation in more than one half of the patients. The disease involves the lower lung zones more often than the upper lung zones.77 Small nodular opacities can be seen in 10% to 50% of patients.78

In a small percentage of patients, large nodules may be seen78; rarely, reticulonodular infiltrates occur.74 It is speculated that this latter finding identifies a subset of COP that may not respond to therapy. Opacities may be recurrent and/or migratory.79,80 Lung volumes are normal in most patients, and pleural effusions rarely occur.75,76,81

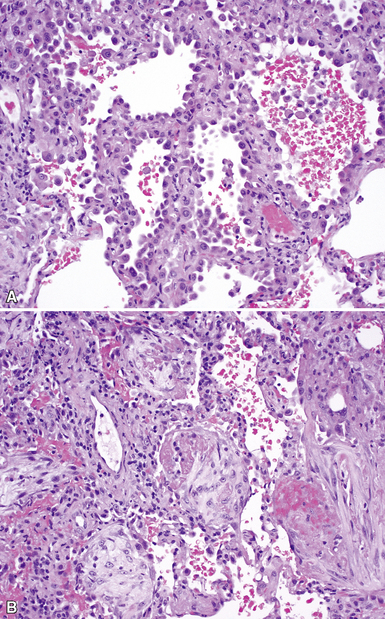

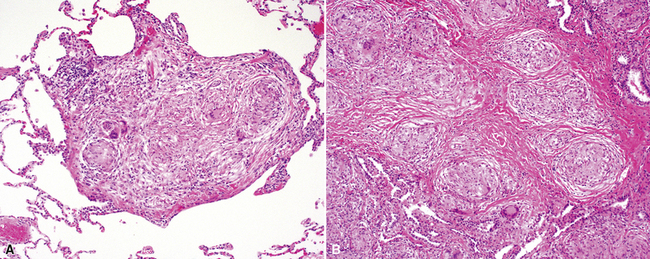

Histopathologic Findings

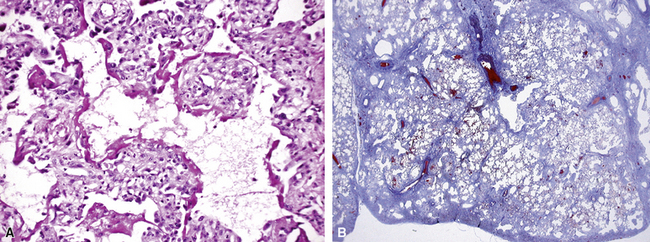

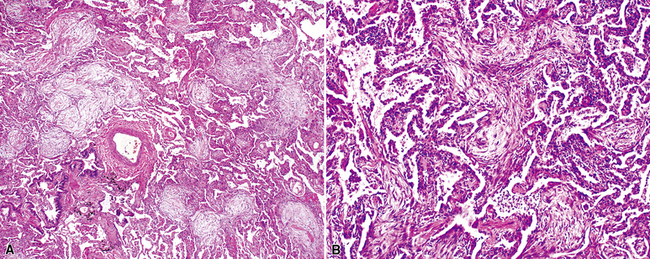

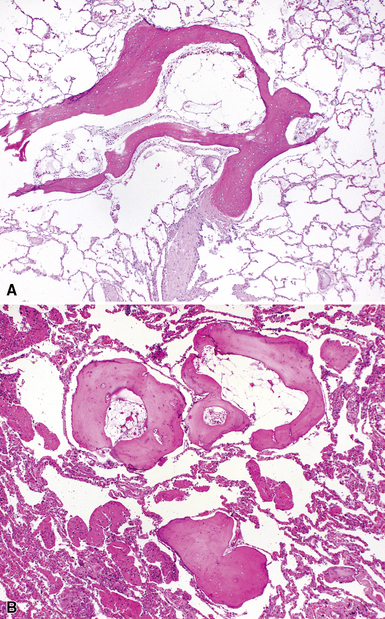

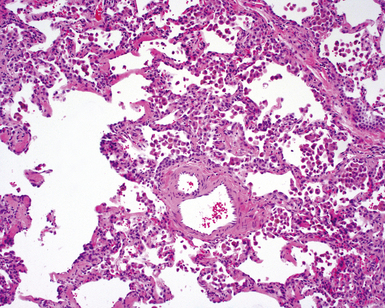

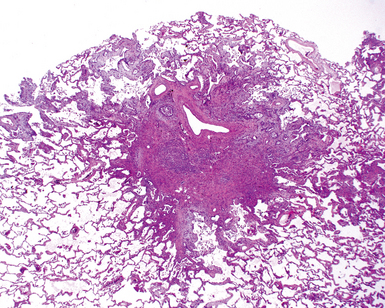

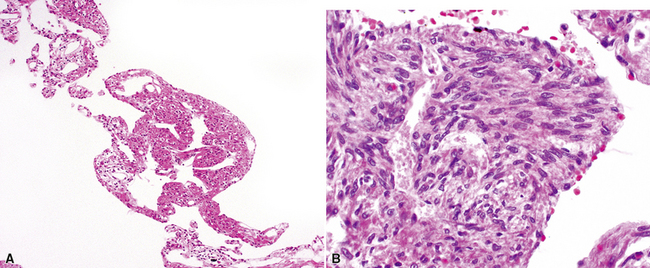

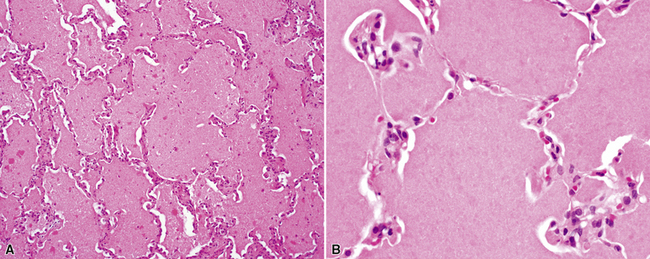

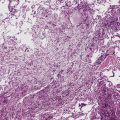

The organizing pneumonia pattern is characterized by variably dense air space aggregates of fibroblasts in ground substance (immature collagen matrix) (Fig. 7-18). This alveolar filling process can be seen to extend into or from terminal bronchioles (Fig. 7-19). Typically, the lung architecture is preserved in COP, and lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes are present in variable numbers within the interstitium17,82,83 (Fig. 7-20). Fibrin may be seen focally in association with air space organization (Fig. 7-21). Alveolar macrophage accumulation may be present, attesting to some degree of airway obstruction. 17,82,83 When air space organization is confluent and diffuse in the biopsy, COP is less likely to be the accurate diagnosis. Interstitial fibrosis and honeycomb lung remodeling are not components of the cryptogenic (idiopathic) form of organizing pneumonia. 17,82,83

Treatment and Prognosis

The expected response to systemic corticosteroid administration therapy is excellent.17,79,84 Because relapses may occur if therapy is stopped abruptly, patients with COP generally require extended corticosteroid tapering, sometimes over a year or more.17,79,84

Differential Diagnosis

As mentioned previously, the differential diagnosis for the organizing pneumonia histopathologic pattern is too broad in scope to be of clinical use. In general, it is fair to say that the presence of the organizing pneumonia pattern is much more commonly associated with slowly organizing infection, systemic connective tissue diseases, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and idiosyncratic reaction to drug or medication, rather than a “cryptogenic” disease. Rarely, air space organization may ossify and produced so-called “racemose” or “dendriform” ossification (Fig. 7-22).

Respiratory Bronchiolitis–Associated Interstitial Lung Disease

Respiratory bronchiolitis (RB) is a histopathologic lesion of the small airways that is common in cigarette smokers.85 In some smokers, an exuberant form of RB occurs as a clinical and radiologic manifestation of diffuse “interstitial” lung disease. This ILD manifestation of RB has been referred to as respiratory bronchiolitis–associated interstitial lung disease (RBILD).86 RB, RBILD, and DIP have been proposed as existing along a continuum in smokers,87 with RB on the asymptomatic end of a spectrum that culminates in DIP on the other. Whether RB, RBILD, and DIP are truly manifestations of a single disease process remains to be proved. Certainly, all three have some histopathologic elements in common, but the two main clinical manifestations in the spectrum (RBILD and DIP) also differ in a number of ways clinically and radiologically.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with RBILD are typically a decade younger than those with DIP and present in early midlife, with a mean age of 36 years in two studies.86,88 A relationship between smoking pack-years and onset of disease suggests a dose-related effect, with a threshold in the vicinity of 30 pack-years. There tends to be a gender predilection toward men,87,89 but men and women were equally affected in one study.88 Mild breathlessness and cough are the most common initial complaints.86,88 Clubbing of the digits is unusual in RBILD.88,90,91 Pulmonary function abnormalities parallel the mild clinical symptoms and may show evidence of both obstruction and restriction, with mild reduction in the diffusing capacity.89

Radiologic Findings

The chest x-ray appearance of RBILD reflects the presence of disease centered on the airways, mainly with thickening of airway walls.87 Ground-glass opacity is seen in more than 50% of chest radiographs in RBILD. On CT scans, ground-glass opacities and centrilobular nodules are typical findings, often best seen at the periphery of the upper lung zones.87

Histopathologic Findings

RB is a common reactive process in the lungs of cigarette smokers; its presence alone does not imply the diffuse lung disease manifestation.91 Moreover, even when the histopathologic changes are diffuse and distinctive in the biopsy specimen, clinical correlation is required for accurate diagnosis. For example, a patient with a lung mass, resected and found to be a bronchogenic carcinoma, may have extensive RB in surrounding lung parenchyma. In the absence of a clinically and radiologically defined ILD, a diagnosis of RBILD would be inappropriate.

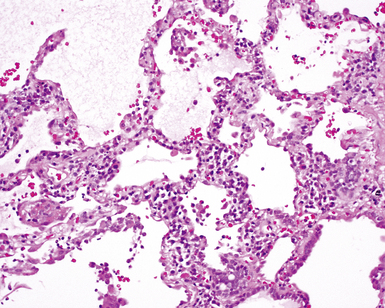

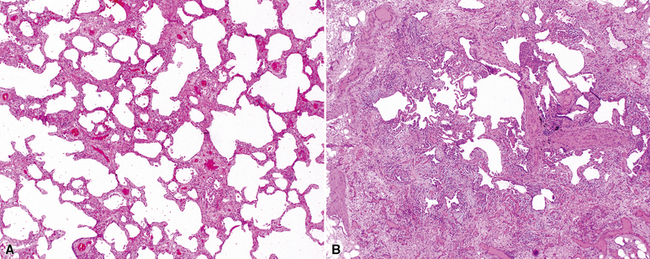

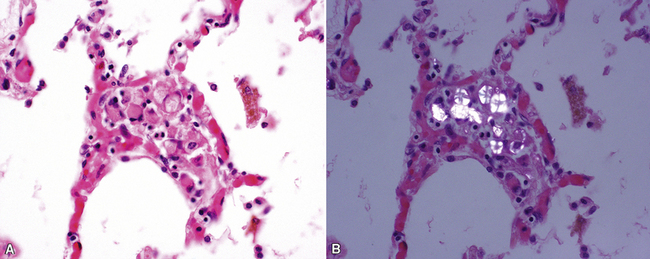

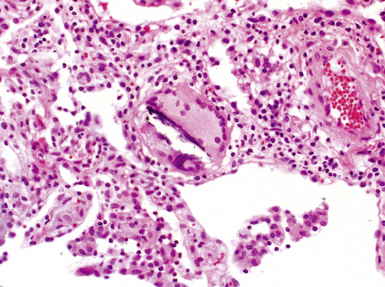

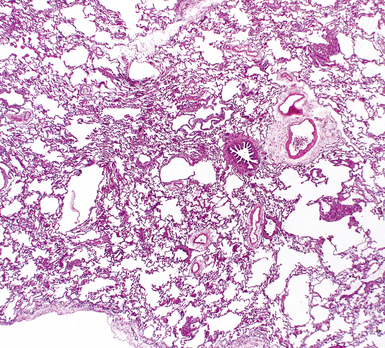

The essential morphologic constituents of RB are (1) scant inflammation around the terminal airways (Fig. 7-23), (2) metaplastic bronchiolar epithelium extending out from terminal airways to involve alveolar ducts (Fig. 7-24), and (3) variable numbers of lightly pigmented, dusty brown air space macrophages within bronchiolar lumens and in immediate surrounding alveoli (Fig. 7-25). Scant peribronchiolar fibrosis may be present and may extend to involve contiguous alveolar walls (Fig. 7-26). When bronchiolocentric scarring is prominent, an alternative diagnosis, such as chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, should be considered. Dense collagenous thickening of the alveolar septa without inflammation can be seen in RBILD. Such fibrosis does not appear to progress to honeycomb fibrosis.92 Presence of fibroblastic foci or destruction of the lung architecture should always raise the possibility of an alternative diagnosis, especially undersampled UIP.

Differential Diagnosis

RB may be confused with bronchiolitis of some other etiology. When bronchiolar metaplasia is a prominent component, distinction from other small-airway disease, such as idiopathic constrictive bronchiolitis, may be difficult. Patients with idiopathic constrictive bronchiolitis in surgical biopsies tend to have more severe pulmonary function abnormalities than patients with RB or RBILD (see Chapter 8 for a discussion of small airways disease).

Clinical Course

RBILD generally carries an excellent prognosis. However, symptomatic or physiologic improvement occurs in a limited number of patients. Smoking cessation, with or without immunosuppressive therapy, has been recommended, but a recent report demonstrated benefit in only a small subset of patients.93

Desquamative Interstitial Pneumonia

Leibow7 proposed the term desquamative interstitial pneumonia for a diffuse lung disease that occurred in patients who were typically 10 years or more younger than patients who developed UIP. The disease often presented in mid-adulthood, and most patients were cigarette smokers.94 Liebow also believed that the “desquamated” cells that filled the air spaces in DIP were epithelial cells. It has now been established that the air space cells of Liebow’s DIP are actually macrophages, and that DIP is not a credible precursor lesion for UIP, as was proposed by a number of authorities.

Clinical Presentation

As currently defined, DIP is a very rare smoking-related lung disease. Patients with DIP are typically older than those with RBILD87 and roughly a decade younger than those with UIP.91,94 Most patients with DIP are cigarette smokers; men are more frequently affected than women. Like UIP, the clinical presentation is dominated by insidious onset of dyspnea and dry cough over several weeks or months.91,95 Digital clubbing is present in 50% of patients with DIP, a finding in sharp contrast with RBILD. The symptoms of DIP are usually more pronounced and more severe than those of RBILD,87 supported by pulmonary function testing showing mild restriction and moderate reduction in diffusing capacity.95

Radiologic Findings

The chest radiograph may be normal in 3% to 22% of patients. When abnormalities are present, patchy areas of ground-glass opacification predominate. The lung bases and periphery are most commonly affected.87,96,97 On CT scans, ground-glass opacification is universally present, mostly in a bibasilar distribution.96 Linear and reticular opacities may accompany ground-glass opacities at the bases but tend to be quite limited in extent. Focal areas of peripheral honeycombing may be identified in as many as one third of patients,96 but when prominent and associated with more pronounced reticular abnormalities, an alternate diagnosis should be considered (probably UIP).

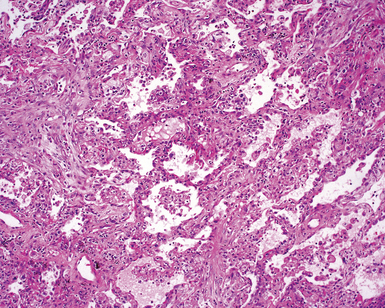

Histopathologic Findings

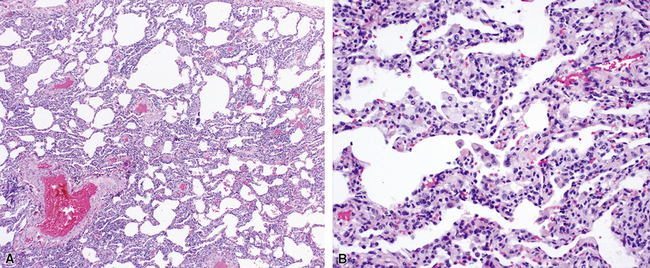

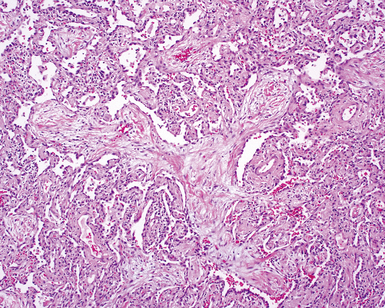

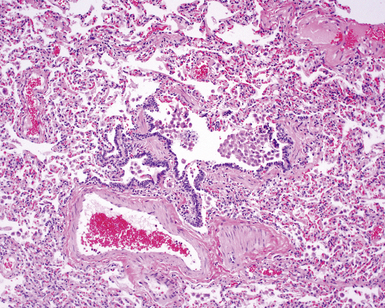

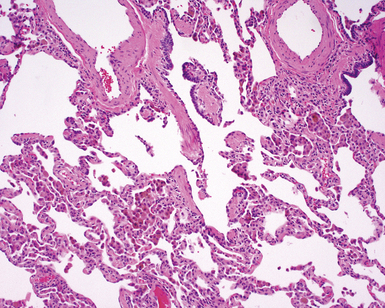

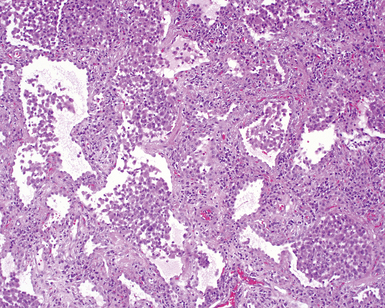

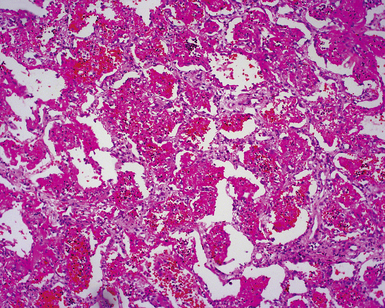

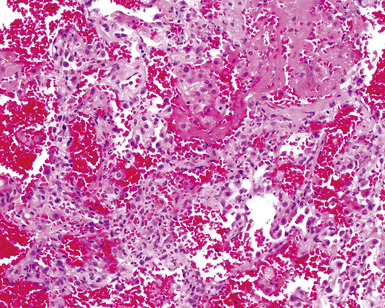

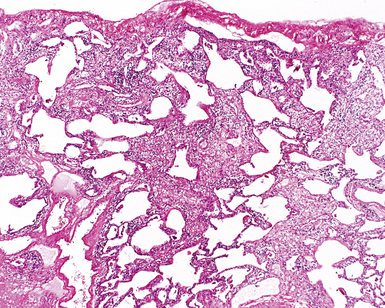

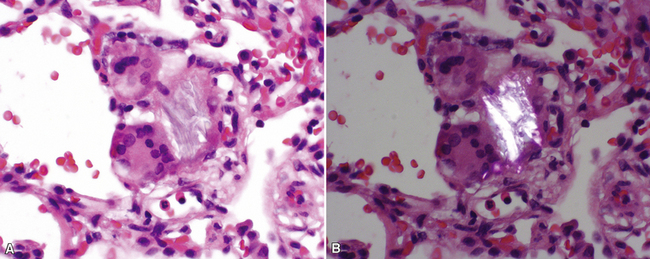

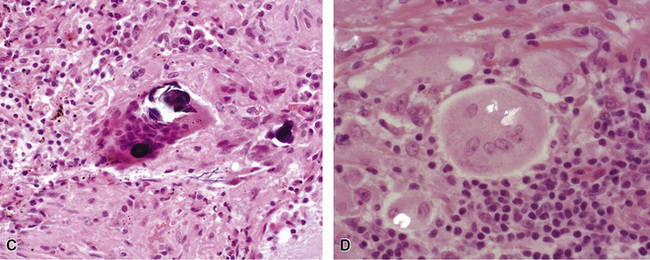

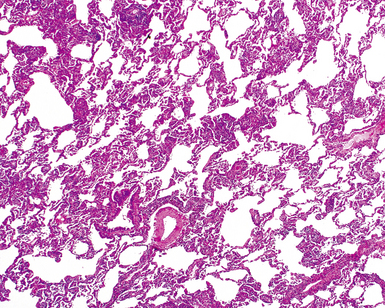

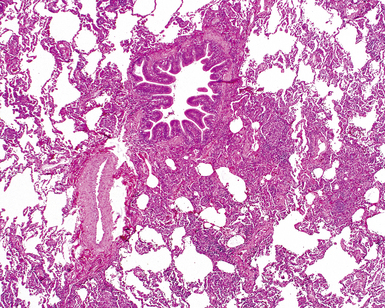

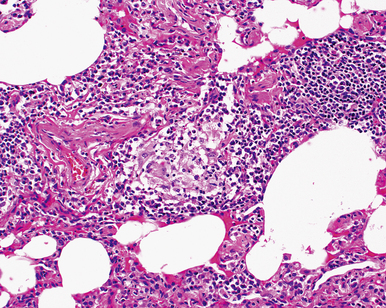

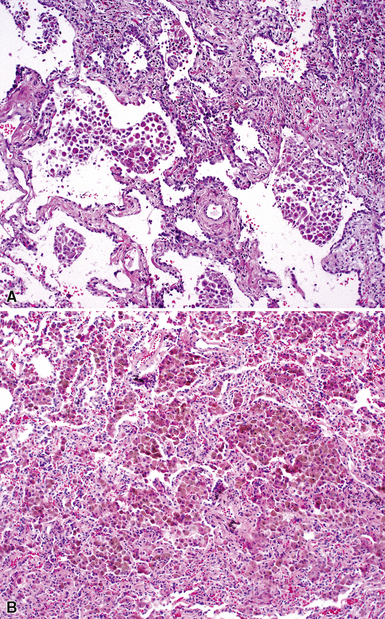

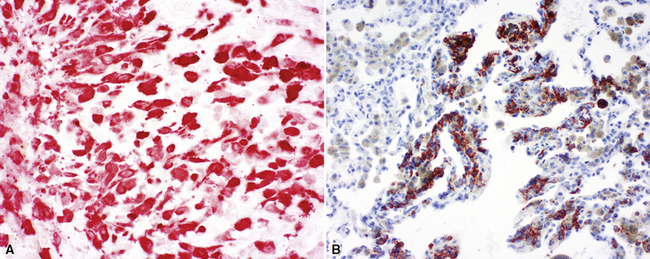

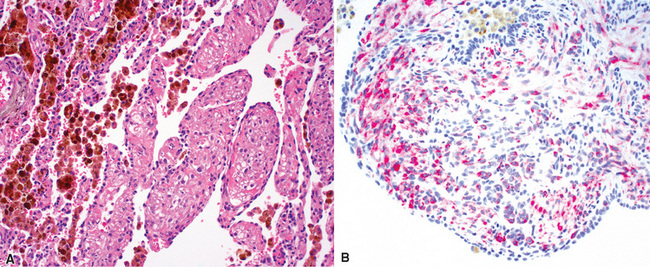

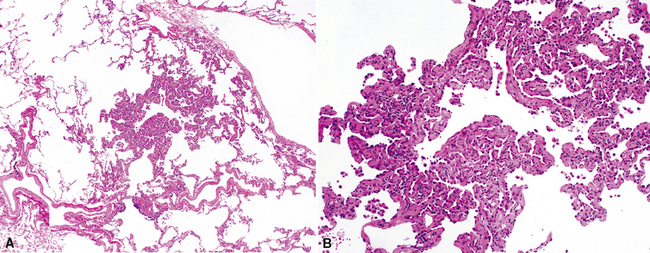

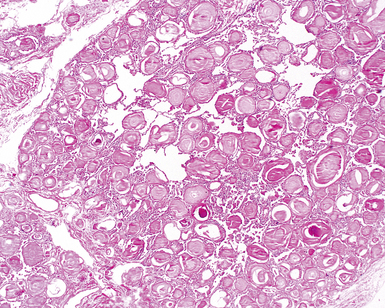

On scanning magnification, the surgical lung biopsy in DIP has an eosinophilic appearance due to the presence of eosinophilic macrophages uniformly filling air spaces11,88 (Fig. 7-27). Mild interstitial thickening by fibrous tissue is the rule and is uniform in appearance (Fig. 7-28). When chronic inflammation is evident at scanning magnification, it is centrilobular and associated with respiratory bronchioles (Fig. 7-29). Scant numbers of plasma cells and rare eosinophils may be seen within slightly thickened alveolar walls at high magnification (Fig. 7-30).

Lymphoid Interstitial Pneumonia

LIP was originally conceived as a chronic cellular interstitial pneumonia with distinctive histopathologic features, quite different in cellular composition and form from Liebow’s other IIPs (e.g., UIP, BIP, DIP, GIP).7 LIP became controversial because many of the cases originally classified as LIP by Liebow (and his contemporaries) evolved into (or were actually indolent forms of) low-grade lymphoproliferative disease involving the lung.98–100 It is now generally acknowledged that the accrual of dense lymphoid tissue in the lung carries strong implications for lymphoproliferative disease, especially small B cell lymphomas of extranodal marginal zone type (so-called lymphomas of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue [MALT]) and polymorphous lymphoproliferative disorders associated with viral infection, including EBV or HTLV-1.98–103 “Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia,” as currently defined, is included as an entity in this chapter because a recent international consensus panel chose to keep LIP as a form of IIP, partly for historical reasons. The panel participants acknowledged that many pulmonary pathologists might classify the described histopathologic findings of “idiopathic LIP” as a cellular form of NSIP.

More recently, Cha and colleagues104 described a series of non-lymphoma LIP cases in which 9 of 15 patients were found to have a CVD, mainly Sjögren syndrome. In that series, three patients with idiopathic LIP were identified. All three survived longer than 10 years, and their disease did not progress to lymphoma or leukemia, despite the fact that one of them had a monoclonal gammopathy.104

Clinical Presentation

The clinical manifestations of the idiopathic form of the LIP pattern are not well studied but seem to be similar to those associated with definable systemic conditions, such as CVD. Women are more commonly affected than men; patients are typically between 40 and 50 years of age.105 Interestingly, all of the “idiopathic LIP” patients described by Cha and colleagues were men, whereas most of secondary LIP patients were women.104 Slowly progressive breathlessness is a common feature, with or without nonproductive cough; the disease may evolve over months or years.

In the classic description of LIP, systemic signs and symptoms such as weight loss, pleuritic pain, arthralgias, adenopathy, and fever were reported, depending on whether an associated systemic condition was present.105–107 Findings may include bibasilar crackles, cyanosis, and clubbing. Immunoglobulin abnormalities in serum are present in some patients.108 More commonly, the LIP pattern is associated with a systemic condition that dominates the clinical presentation and clinical course (e.g., Sjögren syndrome, pernicious anemia, hypogammaglobulinemia).

Radiologic Findings

The published radiologic features of idiopathic LIP seem to describe more than one pattern of disease.109 Bibasilar reticular opacities along with ground-glass attenuation and thickening of interlobular septa are frequently observed abnormalities.104,109–111 There may be mixed alveolar and interstitial infiltrates and thin-walled cysts, honeycombing, and changes suggesting pulmonary hypertension late in the disease.112,113 Nodular patterns can also occur.114 Pleural effusion is rare and, if present, should increase concern for low-grade malignant lymphoma.

A distinctive cystic disease has also been referred to by radiologists as “lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia” (or simply, LIP); on biopsy, however, the process has no significant interstitial inflammatory infiltrates or fibrosis, exhibiting only thin-walled, dilated airways with scant associated bronchiolitis.115 An association with Sjögren syndrome has been documented.116

Histopathologic Findings

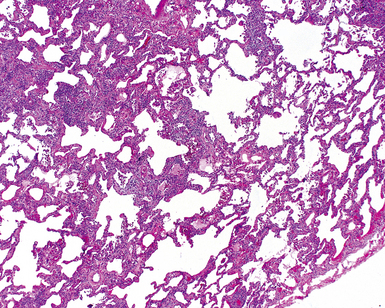

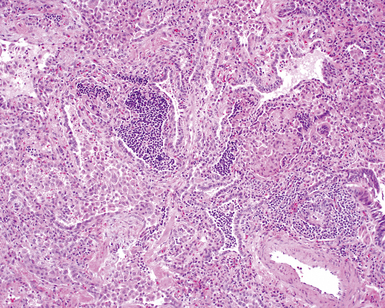

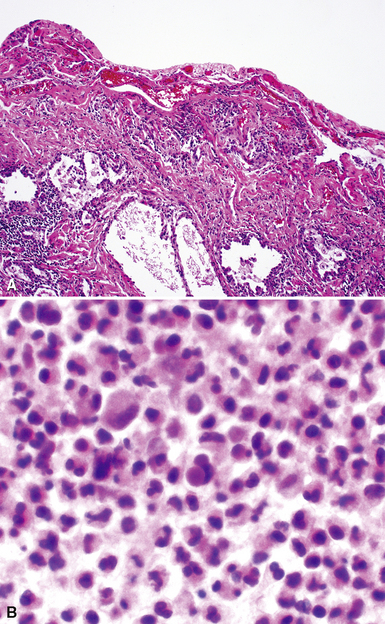

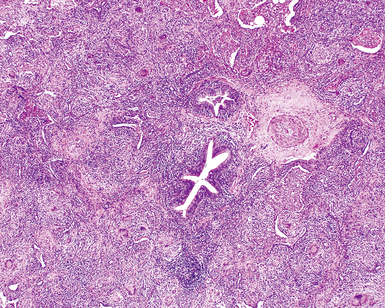

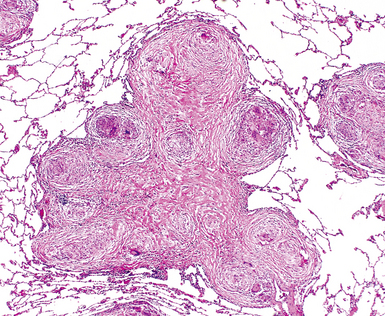

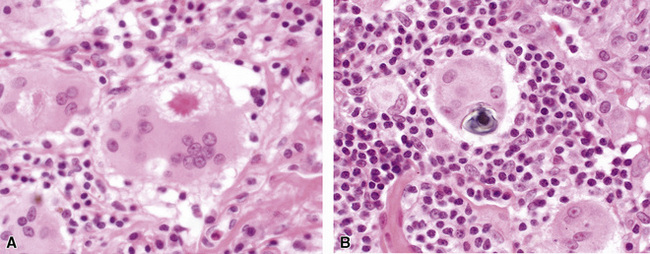

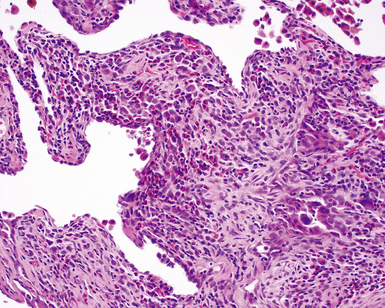

The histopathologic pattern in LIP is characterized by the presence of a dense and diffuse alveolar septal infiltrate made up of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes (Fig. 7-31). This definition helps exclude diseases with less intense cellular interstitial infiltrates, such as certain hypersensitivity reactions and systemic connective tissue diseases. Multinucleated giant cells or small, ill-defined granulomas in the interstitium have been described in the idiopathic form of LIP, but microscopic honeycomb remodeling, with some interstitial fibrosis (Fig. 7-32), can also be a part of idiopathic LIP. To a variable extent, germinal centers may be present along airways and lymphatic routes (Fig. 7-33). When these are prominent and interstitial lymphocytic infiltration is less remarkable, diffuse lymphoid hyperplasia has been used as a preferable term. In this situation, lymphoproliferative disorders, such as multicentric Castleman disease, idiopathic plasmacytic lymphadenopathy with hyperimmunoglobulinemia, or even MALT lymphoma, are the main considerations.117 When the idiopathic form of the LIP pattern is identified, immunophenotyping and gene rearrangement studies typically show an absence of clonality.118 When nodular lymphoid hyperplasia is prominent around bronchioles, typically accompanied by an interstitial infiltrate, Sjögren syndrome should be rigorously investigated as a potential etiology.

Differential Diagnosis

The LIP pattern is most consistently seen when systemic CVDs manifest in the lung.105,119 The LIP pattern may also be seen in the setting of bone marrow transplantation120 and has frequently been observed in both children and adults who have congenital or acquired immunodeficiency syndromes121 and in the setting of adult HIV infection including vertical transmission from mother to child.122–124

Much of what has been written about the histopathology of LIP is similar to that written about the histopathologic patterns of NSIP. If LIP and cellular NSIP can be distinguished from each other microscopically, it is usually on the basis of the sheer density of the lymphoid infiltrate in LIP, accompanied by fibrosis and some degree of remodeling (the latter would be unexpected for the cellular form of NSIP). Naturally, in this setting, gene rearrangement studies are important in distinguishing idiopathic LIP from low-grade lymphoproliferative disease (see Chapter 15 for further discussion). Once the pattern is established, it is useful to suggest the potential systemic conditions that may be associated with this pattern (Box 7-9) in a “comment” section of the surgical pathology report.

Box 7-9 Systemic Conditions Associated with the Lymphoid Interstitial Pneumonia Histopathologic Pattern

Modified from Leslie K, Colby T, Swensen S: Anatomic distribution and histopathologic patterns in interstitial lung disease. In: Schwarz M, King TJ, eds. Interstitial Lung Disease. Hamilton, ON: BC Decker; 2002:31–50.

Clinical Course

The clinical outcome and response to therapy for patients with the LIP pattern is largely dependant on whether systemic disease is present. In the idiopathic form, an accurate prognosis has not been forthcoming, although in the series reported by Cha and coworkers, three patients survived more than 10 years.104 In symptomatic patients, corticosteroid administration may result in significant benefit,105 lending further support to LIP’s being an immunologic disease, rather than a neoplastic one, in most instances. When honeycomb cysts, clubbing, or cor pulmonale are present, the prognosis is less favorable, with as many as one third of patients succumbing to the disease.105,114 Infection is a common complication, especially when LIP is associated with dysproteinemia.105,106,125

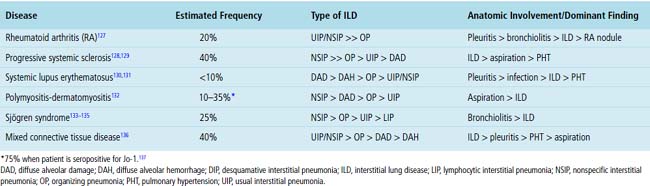

Chronic Manifestations of Systemic Collagen Vascular Disease

Systemic CVDs play an extremely important role in the etiology of ILDs. Knowledge of rheumatic ILD is derived mainly from retrospective studies, typically including small numbers of patients. Because of differences in patient populations reported and in the rheumatic disease severity (and duration) at the time of study, many important questions remain concerning the frequency, pathogenesis, natural history, clinical relevance, and prognosis of ILD occurring in the rheumatic diseases. It is estimated that ILD in CVD is responsible for 1600 deaths annually in the United States, accounting for roughly 25% of all ILD deaths and 2% of all deaths from respiratory causes.126 Not suprisingly, most interstitial pneumonia patterns raise CVD as a consideration in the differential diagnosis. On the other hand, certain CVDs are associated with reasonably reproducible findings in the lung.2Table 7-3 summarizes the different patterns of inflammatory lung disease that have been described as lung manifestations of the known connective tissue diseases. The five rheumatic diseases that are more commonly associated with ILD are (1) rheumatoid arthritis (RA), (2) progressive systemic sclerosis (PSS), (3) systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), (4) polymyositis-dermatomyositis (PM-DM), and (5) Sjögren syndrome. The estimated frequency of lung involvement and the patterns produced are presented in Table 7-4. This section is restricted to the more chronic manifestations of these diseases. Acute lung manifestations of the rheumatic diseases are described in Chapter 5.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

RA is a chronic systemic disease that produces symmetrical arthritis and occurs more commonly in women than in men. ILD was not recognized as a manifestation of RA until 1948,138 possibly because lung manifestations of the disease are difficult to recognize on purely clinical grounds. Today, with the use of pulmonary function testing, bronchoalveolar lavage, and CT imaging, significant lung disease is identified in 14% of patients who meet the American College of Rheumatology (formerly the American Rheumatism Association) criteria for RA; subclinical disease is seen in as many as 44%.139 Interestingly, men are three times more likely to develop ILD with RA than are women.25 Clinically significant ILD in RA is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.25

Clinical Presentation

Diffuse lung disease in RA typically is noted in patients with diagnosed RA, but rarely, ILD may precede articular manifestations.140,141 The clinical presentation is dominated by shortness of breath and cough. Adults are more commonly affected than children,142 and despite a higher incidence of RA in women, men with long-standing rheumatoid disease and subcutaneous nodules seem to develop lung manifestations more often.140 Physical examination may reveal bibasilar inspiratory crackles, digital clubbing, and evidence of cor pulmonale, the last due to pulmonary hypertension arising as a result of hypoxic vasoconstriction.25,140 When fibrosis and honeycomb remodeling accompany diffuse lung disease in RA, UIP enters into the differential diagnosis. Affected patients often are younger than those with idiopathic UIP. Cigarette smoking has been reported to be an independent predictor of lung disease in persons with RA.143

Radiologic Findings

Several radiologic manifestations are described in RA, including reticular opacities with or without honeycombing, airway-associated abnormalities (bronchiectasis, nodules, centrilobular branching lines), and parenchymal opacities.144 When ground-glass infiltrates and reticular opacities are present, there is a predilection for involving the bases and lung periphery. High-resolution CT findings include ground-glass attenuation with mixed alveolar and interstitial infiltrates. As lung disease advances, dense reticular and nodular opacities appear, and honeycomb lung may be seen in late stages of the disease.144,145

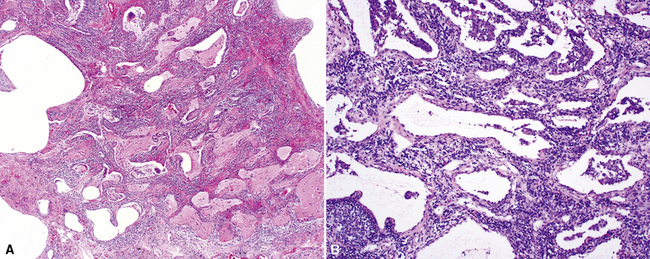

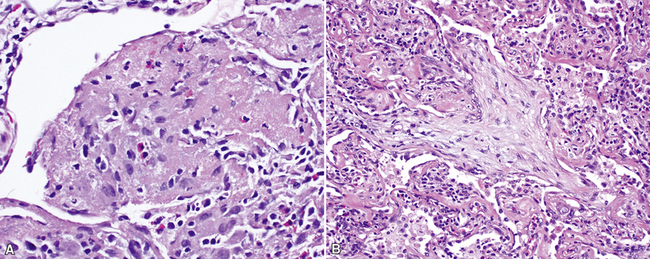

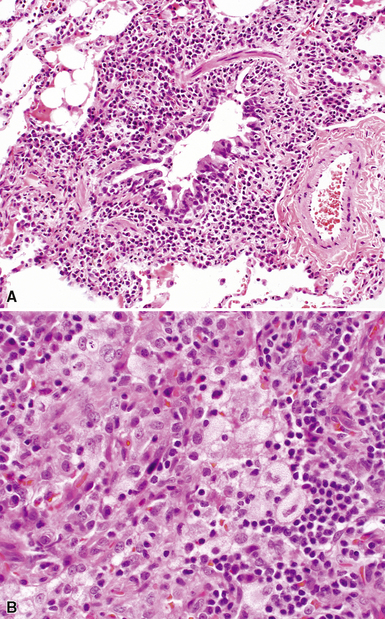

Histopathologic Findings

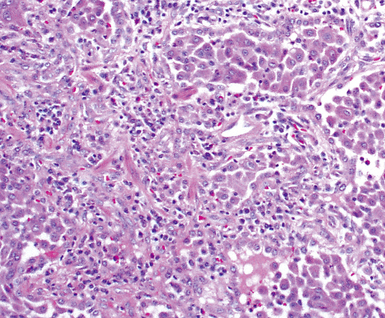

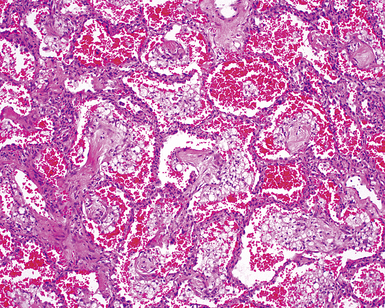

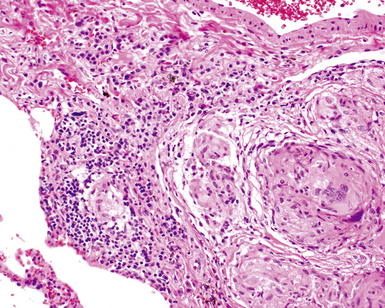

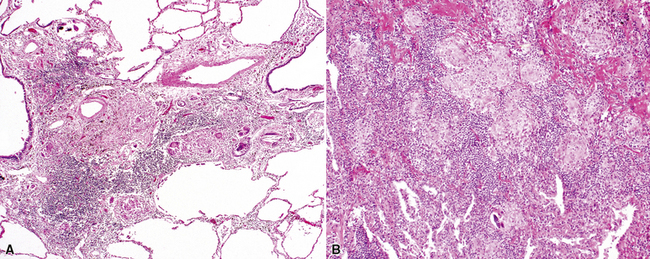

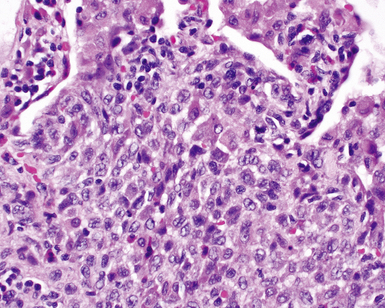

Despite the seemingly nonspecific nature of the histopathologic manifestations of RA, a few key elements emerge on review of many well-documented cases of RA-associated ILD. Chronic inflammation, in the form of lymphocyte aggregates and germinal centers, is typical, although not unique (Fig. 7-34) Most of the lymphoid aggregations are present around the terminal airways (“follicular bronchiolitis” when lymphoid germinal centers are prominent) (Fig. 7-35), but lymphoid follicles may also present in the pleura. In fact, the presence of chronic pleuritis should always raise RA as a consideration in the differential diagnosis. Areas of subacute lung injury, attended by reactive type II cells and air space organization (Fig. 7-36), can be seen with cellular interstitial pneumonia (Fig. 7-37) and variable interstitial fibrosis (Fig. 7-38). This combination of subacute and chronic inflammatory reactions haphazardly involving the same lung biopsy, including the pleura, should raise the possibility of RA lung disease. When fibrosis is prominent, it is often difficult to classify as UIP or NSIP. That may be one of the reasons for the variable reported incidence of these two patterns of fibrosis in the disease. Fibroblastic foci are usually less prominent, and normal lung may be absent. Vasculitis (including capillaritis) and even pulmonary hemorrhage have been described as manifestations of RA lung. When silicosis occurs with RA, the resulting disease is referred to as Caplan syndrome. Rheumatoid nodules can occur in the lung and pleura and must be distinguished from granulomatous infection or Wegener granulomatosis. Intrapulmonary lymph nodes may become prominent in RA and typically show reactive lymphoid hyperplasia when subjected to biopsy.

Clinical Course

As with other connective tissue diseases, therapeutic strategies in RA have focused on immunosuppression.146 Although the reported survival significance of RA-ILD varies, a majority of published papers indicate better survival rates for patients with RA-ILD than for those with UIP/IPF.147 Needless to say, the development of pulmonary fibrosis with a UIP pattern has a significant negative impact on survival.141,143,148,149

Progressive Systemic Sclerosis

PSS is a relatively rare systemic autoimmune disease, with cutaneous manifestations (dermal sclerosis) frequently accompanied by Raynaud phenomenon. Pulmonary involvement (mainly ILD) occurs more commonly in patients with PSS than in those with any other connective tissue disease,128,150 with lung disease ranking fourth in frequency (after skin, peripheral vascular, and esophageal manifestations) in the disease, but is the primary cause of death in PSS.151 As in RA, lung involvement in PSS is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.151

Clinical Presentation

Chronic exertional dyspnea is the most common presentation, followed in frequency by chronic cough. Bibasilar inspiratory crackles are present in two thirds of patients.128,152 Digital clubbing may be present but is uncommon. Pulmonary fibrosis and cor pulmonale may develop eventually.153 As in other CVDs, lung involvement can precede the development of diagnostic systemic manifestations.128,154

Radiologic Findings

Bibasilar interstitial infiltrates with relative sparing of the upper lung zones are typical radiologic features.155,156 Loss of lung volume, honeycomb cysts, and findings consistent with pulmonary hypertension may also be seen. Mixed reticular and nodular infiltrates are common.155,156 Pleural effusion and pleural thickening may occur as minor findings.

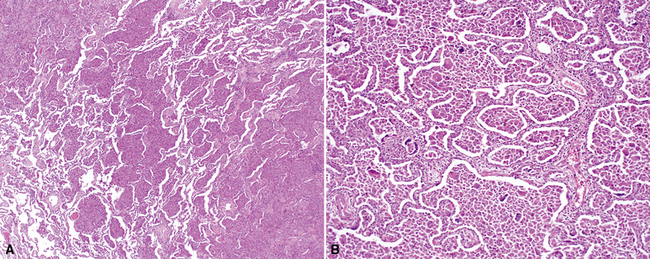

Histopathologic Findings

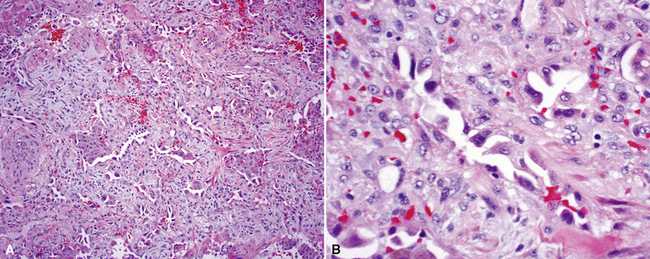

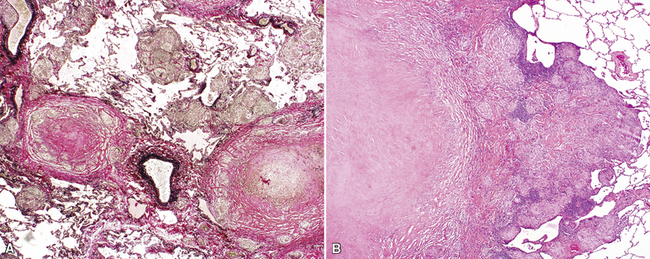

The pulmonary manifestations of PSS can be quite characteristic. The interstitial fibrosis of PSS is paucicellular and diffuse, with preservation of underlying lung architecture (Fig. 7-39). This distinctive “collagenization” of the lung interstitium has been confused with the pattern of lung fibrosis seen in idiopathic UIP.153 The lack of so-called “temporal heterogeneity” (see the earlier section, “Usual Interstitial Pneumonia”) is a useful finding and helps exclude UIP (of IPF) from the differential diagnosis. Pulmonary hypertensive changes (Fig. 7-40) may be present and merit careful attention because this is a major cause of death in patients with scleroderma and lung disease.157 Because patients with PSS can also develop esophageal motility problems, subclinical chronic aspiration should be carefully excluded as a comorbid disease process.158,159

Clinical Course

The mean survival time for patients with scleroderma is 12 years from the time of diagnosis; pulmonary disease has emerged as the major cause of death.160 Pulmonary function status at presentation is a reasonable predictor of survival; high-dose immunosuppressive therapy, typically in combination with a cytotoxic agent, seems to benefit those patients with severe manifestations.161

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

SLE is a chronic systemic autoimmune disorder characterized by arthropathy, mucocutaneous manifestations, renal disease, and serositis.162 The lung may be the major site of involvement in SLE, ranging from acute lupus pneumonitis on one end of the spectrum to fibrotic forms of NSIP on the other.130,163,164 Acute lung injury and pulmonary hemorrhage are more commonly associated with SLE than with other systemic connective tissue diseases,130,165 but hemoptysis occurs only in little more than one half of the affected patients.166,167

Clinical Presentation

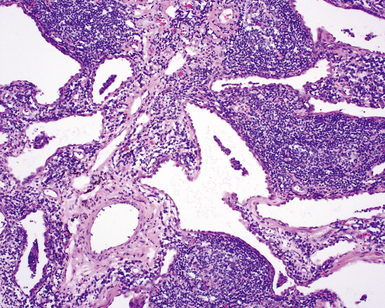

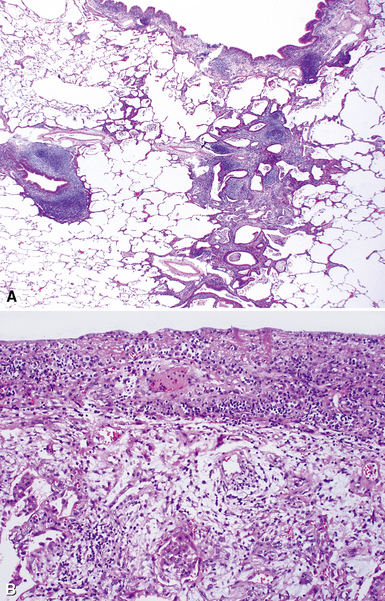

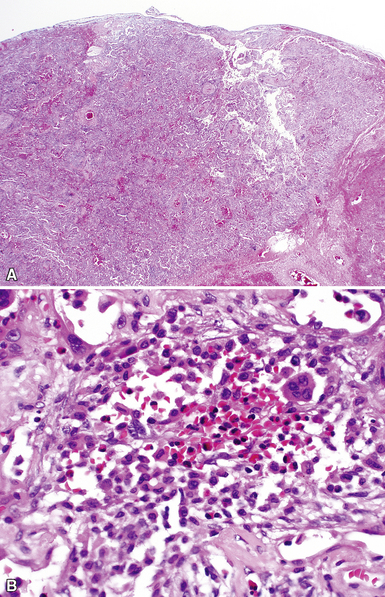

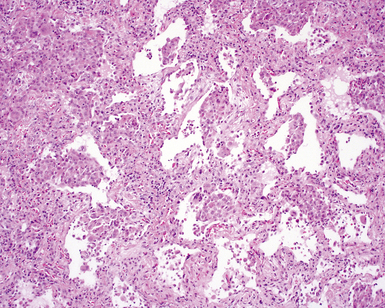

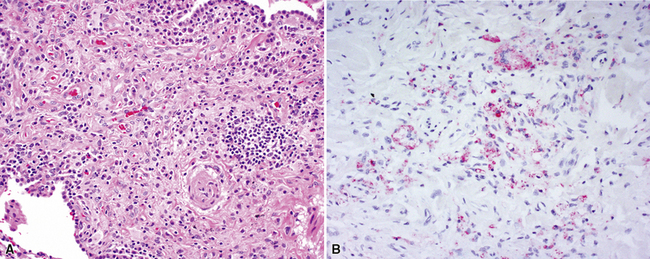

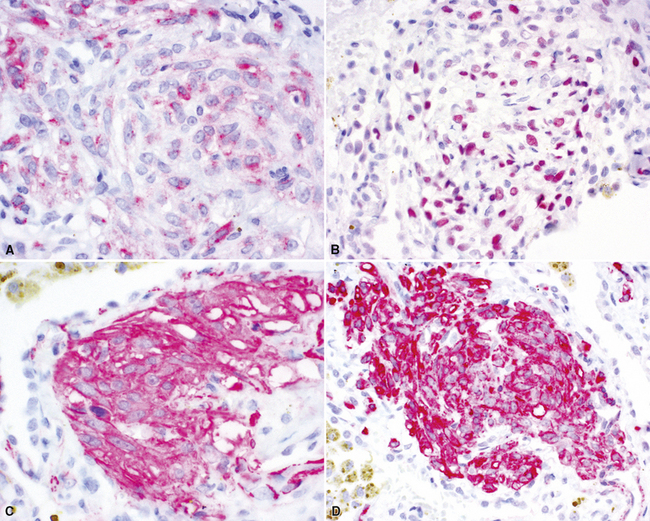

SLE rivals PSS as the leader in pleuropulmonary manifestations in CVD.131,163,168,169 The spectrum of lung disease in SLE is quite broad130,164,165,170 and includes pleuritis (Fig. 7-41), acute lupus pneumonitis (Fig. 7-42), NSIP with fibrosis (Fig. 7-43), and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (Fig. 7-44). Constrictive small-airway disease, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and pulmonary embolism can also occur as rare manifestations. Patients with lung disease often have high serum ANA or RF titers.

Radiologic Findings

The radiologic findings are similar to those in other connective tissue diseases: variable ground-glass attenuation, pleural thickening, pleural and pericardial effusions, and linear parenchymal opacities.130,171–174 Acute pneumonitis can produce more extensive changes, but, rarely, chest radiography and high-resolution CT may show normal findings.175

Histopathologic Findings

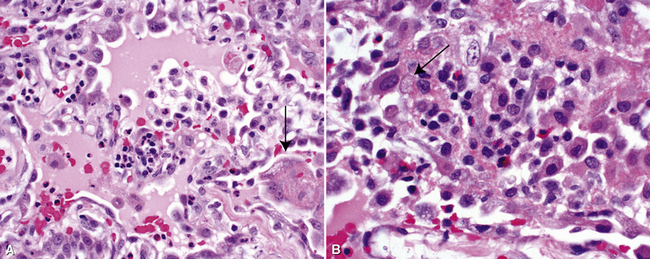

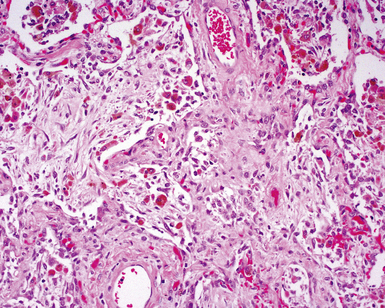

Two general categories of pulmonary disease are described in SLE. The first is acute lupus pneumonitis (ALP). ALP is characterized by alveolitis with variable interstitial inflammation and edema (Fig. 7-45). Siderophages and capillaritis occur to a variable degree (Fig. 7-46). Pleuritis is commonly present. The second category of disease includes cellular interstitial pneumonia (lymphocytes and plasma cells) with variable interstitial fibrosis (Fig. 7-47). This latter NSIP pattern is associated with a better prognosis than that for ALP. When pulmonary hemorrhage occurs, the prognosis may be adversely affected. One dramatic but fortunately rare complication of SLE is the occurrence of lung infarction related to the lupus anticoagulant.176–178 Whenever lung infarction is encountered in a young, otherwise healthy patient, this possibility should be considered (even if the patient does not have evident SLE).

Clinical Course

Systemic corticosteroid therapy may be effective in SLE-associated lung disease, although sometimes the addition of a cytotoxic agent (e.g., cyclophosphamide, azathioprine) may be required.179 Acute lupus pneumonitis carries a reported high mortality rate in some series.168 More chronic forms of diffuse lung disease in SLE have a relatively good prognosis and response to therapy.180

Polymyositis-Dermatomyositis

Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (PM-DM) are inflammatory disorders of the skeletal muscle and dermis. Five groups of primary or secondary disease are recognized, including childhood forms and overlap syndromes.181,182 Pulmonary complications in PM-DM occur less commonly than in other systemic connective tissue diseases, but in a percentage of patients, the pulmonary manifestations can be quite dramatic.183

Clinical Presentation

Although most patients with PM-DM develop lung manifestations after the clinical diagnosis has been established, occasionally lung disease can precede the clinical and serologic diagnosis by months or even years.184 Onset of pulmonary symptoms may occur at any age, with a mean occurrence in the sixth decade.150,184,185 Women are more commonly affected than men. Digital clubbing is rare. In contrast with most other systemic connective tissue diseases (with the exception of SLE), patients with PM-DM can present with acute lung disease, typically manifesting as rapidly progressive DAD.183,185 Importantly, both acute aspiration pneumonitis secondary to underlying respiratory muscle weakness and bronchopneumonia occurring in the setting of immunosuppressive therapy are more common in PM-DM than is chronic diffuse lung disease.186,187

Radiologic Findings

As with other CVDs manifesting in the lung, radiologic abnormalities in PM-DM predominantly affect the lung bases.185 Ikezoe and colleagues reviewed the high-resolution CT findings in 23 of 25 patients with PM-DM who had high-resolution CT abnormalities.188 These researchers identified ground-glass opacities in 92%, linear opacities in 92%, irregular interfaces in 88%, air space consolidation in 52%, parenchymal micronodules in 28%, and honeycombing in 16% of the cases. The most dramatic radiologic finding associated with PM-DM is the rapid onset of air space consolidation associated with the development of DAD.184,185

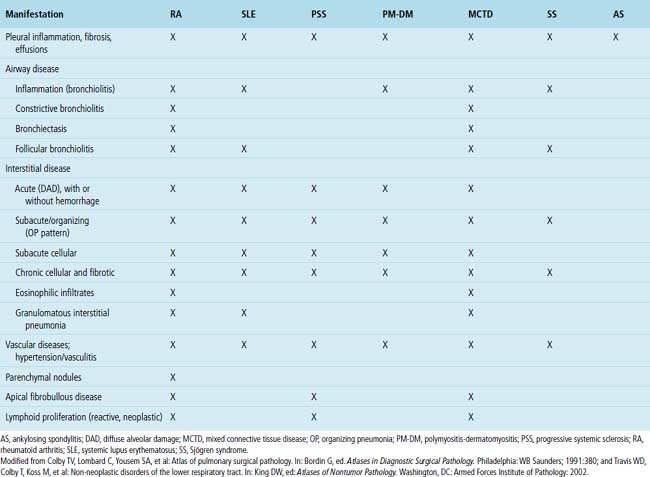

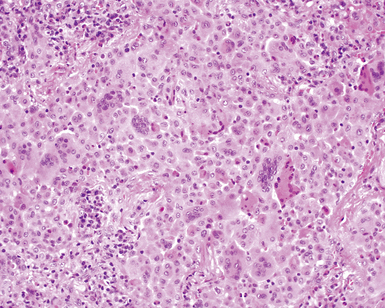

Histopathologic Findings

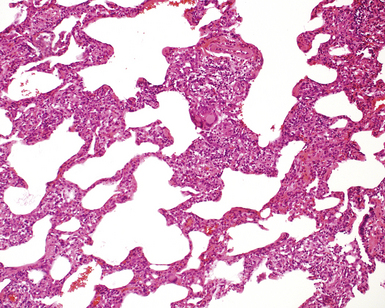

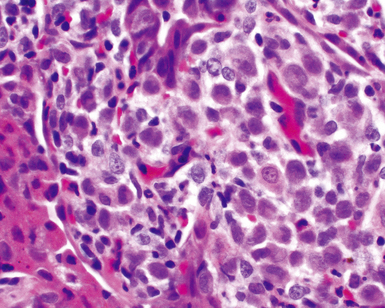

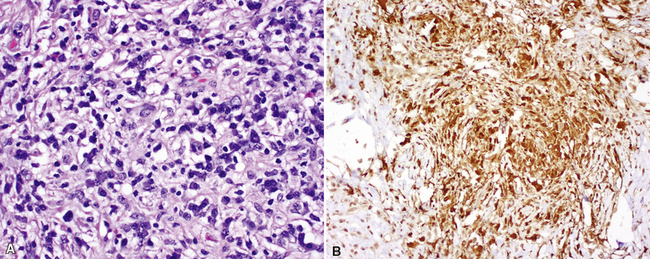

The most frequent lung manifestation of PM-DM is a cellular interstitial pneumonia (Fig. 7-48) with some fibrosis,184,185 indistinguishable from nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (see the later section, “Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias”). The next most common pattern is DAD (Fig. 7-49). The fibrosis associated with PM-DM is distinguishable from that of idiopathic UIP based on a relative lack of peripheral accentuation (Fig. 7-50) and absence of the typical transitions from older lung fibrosis to normal lung through fibroblastic foci. Pleuritis, inflammatory small-airway disease, and pulmonary hypertension are unusual findings; their occurrence should suggest a manifestation of a different connective tissue disease.

Sjögren Syndrome

Sjögren syndrome is an immune-mediated exocrinopathy characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of the salivary glands, with resulting dry mouth and dry eyes.189 Lung involvement is common and is similar to that in other CVDs manifesting in the lung.107,190,191 Sjögren syndrome can occur as a primary connective tissue disease or as a complication associated with other connective tissue diseases (occurrence rates for the two forms are approximately equal).189 In both primary and secondary forms, the consistent pathologic manifestation is that of lymphoid accumulation in a bronchiolocentric distribution and the NSIP/LIP pattern of cellular interstitial pneumonia.

Clinical Presentation

Women are more commonly affected with lung disease in Sjögren syndrome than men; the most frequent presenting complaint is cough and dyspnea.107,190 Positive results on rheumatoid factor and ANA assays are expected findings, as well as positive reactions to extractable nuclear antigens (anti-SSA, anti-SSB).192 These latter serologic tests are specific for the primary form of the disease.193

Radiologic Findings

Mixed alveolar and interstitial infiltrates are characteristic in Sjögren syndrome; they usually have a finely reticular or nodular pattern.191,194 The occurrence of pleural effusion or hilar/mediastinal adenopathy in patients with Sjögren syndrome should raise concern for lymphoma.195

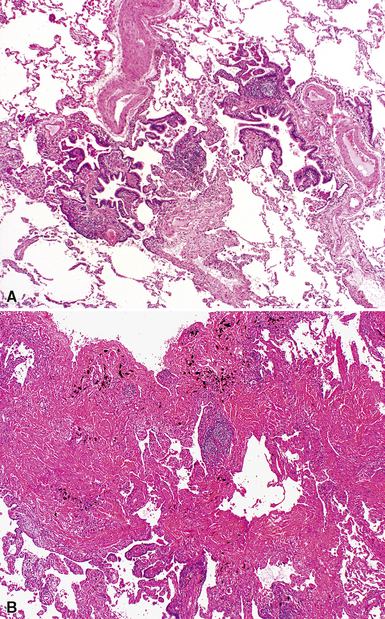

Histopathologic Findings

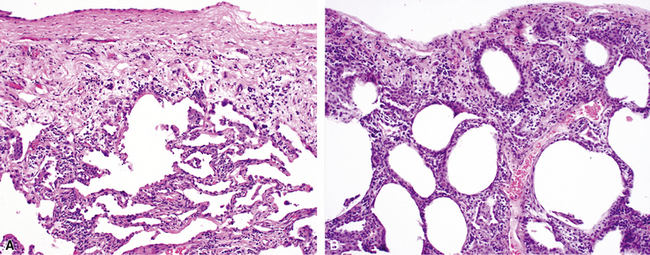

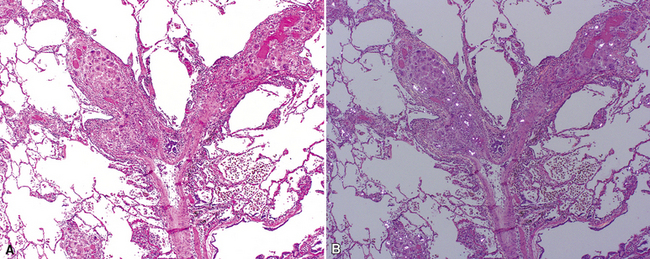

The histopathologic spectrum of pulmonary Sjögren syndrome includes bronchiolitis (Fig. 7-51) with or without air space organization, follicular lymphoid hyperplasia along airways (Fig. 7-52), diffuse NSIP or LIP pattern interstitial inflammation (Fig. 7-53), and rarely, interstitial fibrosis (Fig. 7-54), the last raising concern for an inflammatory version of UIP. Small, non-necrotizing granulomas, resembling those of hypersensitivity pneumonitis, are frequently identified in the interstitium (Fig. 7-55).196 In some cases, more prominent granulomatous inflammation can be seen, especially in association with the LIP pattern of cellular infiltration. Patients with Sjögren syndrome are at risk of developing lymphoid hyperplasia and lymphoproliferative diseases; this predilection should be kept in mind in evaluating the lung biopsy in this setting.

Diffuse Eosinophilic Lung Disease (Pulmonary Eosinophilia)

Several conditions have been described in which the lungs become infiltrated by eosinophils.197,198 An etiologic and clinical classification of the “eosinophil-rich lung diseases” is presented in Box 7-10. Asthma and hypersensitivity play important roles in a number of these. Eosinophilic lung diseases are discussed together here, but in practice, only acute onset of diffuse lung injury accompanied by extravascular eosinophils is relatively predictable in terms of clinical behavior and responsiveness to therapy (i.e., corticosteroids). When pulmonary eosinophilia presents as a chronic condition, the behavior seems to be less predictable. The term chronic eosinophilic pneumonia has been applied in such cases, even though the histopathologic findings in biopsy specimens may not reflect this longer evolution with observable fibrosis or structural remodeling.

Box 7-10 Etiologic and Clinical Classification of Eosinophilic Pneumonia

Modified from Travis WD, Colby T, Koss M, et al: Non-neoplastic disorders of the lower respiratory tract. In: King DW, ed: Atlases of Nontumor Pathology. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology: 2002:161, Table 3-31.

Clinical Features

Patients with the “chronic” form of eosinophilic pneumonia often exhibit a typical clinical syndrome and radiographic appearance.199 The condition frequently affects middle-aged women, and asthma is present in approximately one fourth of the cases. Nasal symptoms occur in roughly one third of affected individuals. The disease typically presents with severe systemic symptoms, including fever, sweats, weight loss, cough, and dyspnea. Peripheral blood eosinophilia can often be identified, but this may be transient or absent altogether.

Radiologic Findings

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia presents the most consistent radiologic pattern, with bilateral, poorly defined, subpleural air space consolidation on chest radiographs, most commonly distributed at the lung apices and in the axillary region. One unifying concept for the diffuse forms of eosinophilic lung disease is the “migratory” infiltrate. These infiltrates may disappear spontaneously and recur in the same position or elsewhere. In the most extreme cases, the infiltrates are densest in the periphery of the lung and spare the central region. This phenomenon has been referred to as the photographic negative of pulmonary edema.199 CT scans detect the peripheral location of infiltrates even when this distribution is not apparent on the chest radiograph.200 Once the characteristic presentation is recognized, corticosteroid administration can lead to dramatic improvement in patients with some forms of the disease and may even be used as a diagnostic test. Atypical presentations occur, so surgical wedge biopsy may be required to establish the diagnosis.

Histopathologic Findings

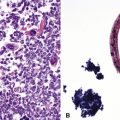

The histopathologic features of chronic pulmonary eosinophilia are similar to those of the acute form; it has been said that the distinction must rely on the clinical course rather than on the constellation of morphologic findings.1 Alveolar spaces are filled with eosinophils and plump eosinophilic macrophages (Fig. 7-56), and there is an associated mild interstitial pneumonia. Type II hyperplasia is characteristic (Fig. 7-57), and fibrin often is present in the air spaces (Fig. 7-58). Angiitis of small vessels may be seen, and patchy air space and alveolar duct organization may be present. A vaguely granulomatous accumulation of dense macrophages may be seen within the alveolar spaces (Fig. 7-59), sometimes accompanied by multinucleate giant cells whose nuclei and cytoplasm closely resemble those of adjacent macrophages (Fig. 7-60). Chronicity may be suggested by the presence of variable interstitial fibrosis on histopathologic examination, but as mentioned earlier, this is not a prerequisite for the diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

When air space organization is prominent, disorders with the organizing pneumonia pattern must be considered in the differential diagnosis (see Box 7-8). Some investigators have proposed an overlap syndrome between COP and eosinophilic pneumonia with subacute clinical course; it is interesting that both conditions are expected to have favorable responses to systemic corticosteroid administration. When corticosteroids have been administered before biopsy (which is quite common), eosinophils may be absent or inconspicuous in lung sections. In such cases, the differential diagnosis may include granulomatous disease if the dense histiocytic response and multinucleate giant cells dominate the picture. When fibrin is prominent in the setting of pretreatment with corticosteroids, generic acute lung injury (including DAD and acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia, because both patterns can be seen in acute eosinophilic pneumonia [AEP]; see Chapter 5) may enter the histopathologic differential diagnosis. Some patients with long-standing symptoms may have fibrosis on biopsy; in such cases, a fibrosing lung disease, such as UIP or NSIP, may enter the differential diagnosis, with eosinophilic pneumonia possibly manifesting as a comorbid process (e.g., drug reaction superimposed on NSIP).

Clinical Course

The clinical course is somewhat dependent on the underlying cause of the eosinophilic pneumonia, but in general, most affected individuals will benefit from high-dose corticosteroid therapy (although the speed of recovery may not be as rapid as that seen in acute onset eosinophilic pneumonia). As in all cases of eosinophilic pneumonia, it is always worthwhile to suggest the possibility of Churg-Strauss syndrome (see Chapter 10) because the pulmonary manifestations of that systemic vasculitic disease in the lung are most commonly those of eosinophilic pneumonia.

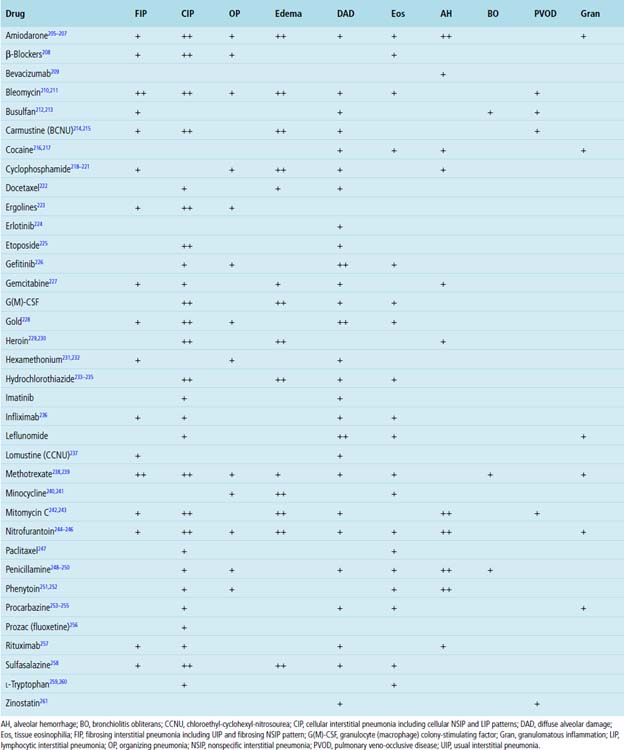

Drug-Associated Diffuse Lung Disease

An increasing number of medications have been implicated in chronic diffuse lung disease.201,202 Three distinct forms are recognized: (1) drug-mediated chronic diffuse lung disease, (2) acute lung injury associated with drug administration, and (3) vascular diseases produced by medications.203,204 The latter two conditions are dealt with in Chapters 5 and 10, respectively.

The recognition of drug-induced diffuse lung disease is a major challenge in lung pathology because most of the histopathologic changes identified are nonspecific (Table 7-5) and simulate those seen with other causes of diffuse lung disease.262 Moreover, many affected patients have underlying diseases for which a drug has been administered, and some of these diseases also have pulmonary manifestations. The diagnosis of a drug-mediated diffuse lung disease requires careful exclusion of other causes.262 Unfortunately, a clear onset of pulmonary symptoms with drug administration and abatement of symptoms on cessation of the drug may not be easily discernable. Clinical information regarding specific drug type, dose, and timing of administration relative to onset of symptoms is essential to an accurate diagnosis.

General Histopathologic Findings

Most of the inflammatory changes in the lung related to drug toxicity are nonspecific. More often than not, a mixture of both acute and chronic disease is apparent and can be a clue to the diagnosis of drug-mediated injury.238 In chronic drug toxicity, lung fibrosis may occur, sometimes with honeycomb remodeling. In such cases, UIP may be simulated. Type II cell hyperplasia with or without atypia, cytoplasmic vacuolation in type II cells and macrophages, and tissue eosinophilia can occur in drug reactions. Also, some drugs are associated with the production in the lung of small, poorly formed granulomas, simulating infection, hypersensitivity, or even Sjögren syndrome.201

General Treatment and Prognosis

Most patients with drug-mediated diffuse lung disease have a favorable prognosis when the implicated drug is withdrawn. Certain newer targeted molecular therapies have been associated with a higher mortality rate when diffuse acute injury occurs.224,263 Once fibrosis has occurred, changes are likely to be stable, with little improvement. Systemic corticosteroid therapy may be added when symptoms are severe.

Specific Drugs Associated with Interstitial Lung Disease

Methotrexate

Methotrexate (MTX) lung toxicity is uncommon; when it occurs, it is predominantly a manifestation in women taking the drug.264,265 Because MTX is used in the treatment of a variety of disorders (e.g., RA, some leukemias, some visceral cancers), these tend to be the associated underlying diseases that must be considered in the differential diagnosis for the lung manifestations identified. Interstitial inflammation and fibrosis (Fig. 7-61) are common findings in the surgical lung biopsy.239,266,267Giant cells and small non-necrotizing granulomas (Fig. 7-62) are the only relatively specific markers for MTX, in comparison with other drugs.239 Type II pneumocyte hyperplasia and tissue eosinophilia may be seen (Fig. 7-63). Hyaline membranes are rarely identified.239

Amiodarone