14 Chronic diarrhoea and fatty stools

Case

A 48-year-old man presents with a history of frequent watery diarrhoea for the last 3 months, up to six times daily. He travelled to Southeast Asia, including Thailand, 3 months ago. There has been no blood in the stools and they have not been excessively pale or difficult to flush away. After he drinks milk or eats gluten-containing foods, his symptoms are worse.

Introduction

Chronic diarrhoea can be simply defined as the frequent or urgent passage of unformed stool for at least one month. As with acute diarrhoea (Ch 13), a careful history and physical examination will often help suggest the diagnosis and direct investigations.

History

The clinician needs to determine what the patient means by diarrhoea. The patient should be asked about the frequency and consistency of the stools. Diarrhoea needs to be distinguished from rectal urgency alone or faecal incontinence (Ch 16).

Clues to the cause of the diarrhoea can be obtained from the history and examination (Table 14.1). Small-volume, frequent stools suggest large bowel disease and tenesmus (a constant sense of the need to defecate) suggests rectal involvement. Large-volume, watery stools are consistent with small bowel disease, whereas obvious clinical steatorrhoea with pale, bulky, oily stools that float suggests the presence of small bowel or pancreatic disease.

| Clinical feature | Conditions to consider |

|---|---|

| Young age | Coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, lactase deficiency, irritable bowel syndrome |

| Oil droplets in stool | Pancreatic insufficiency |

| Previous surgery | Bacterial overgrowth, dumping, post vagotomy diarrhoea, ileal resection, short bowel syndrome |

| Peptic ulcer | Zollinger-Ellison syndrome |

| Medications | Laxatives, magnesium antacids, antibiotics, lactulose, colchicine |

| Frequent infections | Immunoglobulin deficiency |

| Marked weight loss | Thyrotoxicosis, malignancy, malabsorption |

| Arthritis | Inflammatory bowel disease, Whipple’s disease, hypogammaglobulinaemia, Yersinia spp. |

| Hyperpigmentation | Whipple’s disease, Addison’s disease, coeliac disease |

| Fever | HIV, inflammatory bowel disease, lymphoma, Whipple’s disease |

| Flushing | Carcinoid syndrome |

| Chronic lung disease | Cystic fibrosis |

| Neuropathy | Diabetes mellitus, vitamin B12 deficiency, amyloidosis |

| Family history of diarrhoea | Colon cancer, coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease |

The presence of blood may indicate local anal bleeding or other colonic disease. Bright red blood that is separate from the stool is consistent with an anal or rectal cause, but may occur with more proximal colonic disease. Altered blood, or blood with the stool is in keeping with higher colonic bleeding, such as from inflammatory bowel disease or colon cancer (Ch 10).

Symptoms associated with the diarrhoea may also provide valuable information about the nature of the underlying disease process. Weight loss suggests an organic disorder and may be marked with malabsorption, carcinoma or inflammatory bowel disease. Large joint arthritis or sacroileitis suggests inflammatory bowel disease. Yersinia infection and Whipple’s disease can also present with arthritis.

Physical Examination

Evidence of malnutrition and wasting should be sought and the skin examined for rashes, pigmentation and evidence of nutritional deficiency. There may be evidence of iron deficiency (pallor, cheilosis, glossitis and koilonychias) or vitamin B12 deficiency (peripheral neuropathy, glossitis and knuckle pigmentation). Protein deficiency may result in peripheral oedema and white nails.

Further clues to the cause of diarrhoea may be obtained from abdominal examination. An abdominal mass or liver secondaries may be identified. A rectal mass may be present on rectal examination, or faecal impaction, particularly in elderly patients, may be noted and sphincteric tone should be tested to rule out faecal incontinence. Perianal disease with fissures, fistulae and abscesses is common in Crohn’s disease (Ch 12).

Assessment

The history and physical examination will often direct the order and nature of investigations.

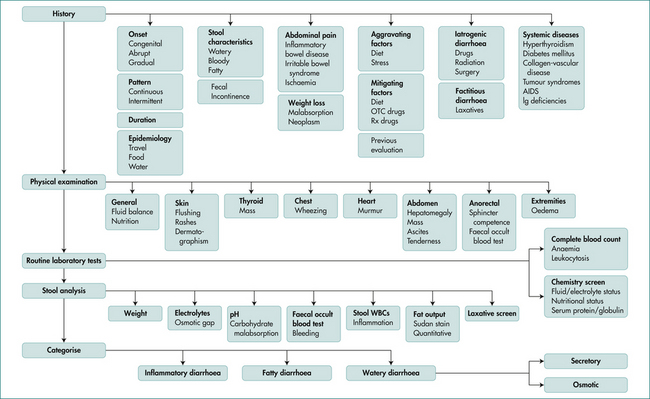

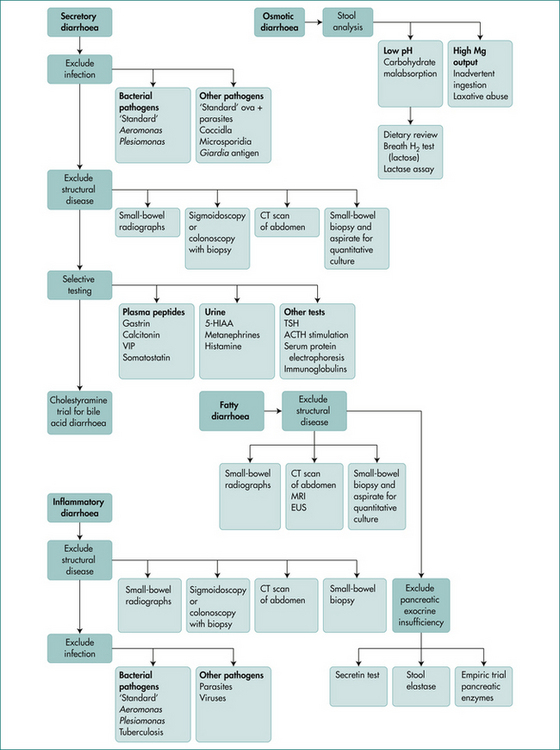

Categorising the pattern of diarrhoea into osmotic (ceases on fasting), secretory (persists in fasted state), inflammatory (passage of blood) and classical steatorrhoea helps in directing investigations though overlap can occur. (See Figs 14.1 and 14.2.)

Malabsorption

The basic physiological problem the body faces in assimilation of food is the passage of nutrients across the limiting cell membrane of the enterocyte. The problem is solved by breaking food particles down to basic components (digestion) and the insertion of special carrier proteins into the absorptive cells to facilitate absorption. The term ‘malabsorption’ is generally used to encompass both impaired digestion and defective absorption. A classification of malabsorption is shown in Box 14.1.

Box 14.1 Classification of malabsorption and example of causes

Physiology

Understanding malabsorption requires knowledge of the physiology of normal digestion and absorption.

The enterocyte

The small intestine is lined by specialised cells called enterocytes and, like all cells, they are surrounded by a limiting membrane (a lipid bilayer) with the function of preventing the loss of cytosol and the entry of unwanted molecules. The purpose of digestion is to break down nutrients into molecules small enough to be absorbed. The lipid bilayer allows diffusion of fats into the cell and is equipped with carriers to enable the absorption of sugar and amino acids. Anatomical modifications in the small intestine (valvulae conniventes, villi and microvilli) increase the luminal surface area by approximately 600-fold.

Fat assimilation

Enterocytes absorb free fatty acids and monoglycerides and carry fats to the interior surface membrane. Bile salts are finally absorbed in the terminal ileum. Within the enterocyte, monoglycerides are re-esterified to triglycerides and coated with small amounts of protein to form a chylomicron. These pass into the mesenteric lymphatics and enter the blood stream via the thoracic duct.

Clinical Approach to the Patient with Malabsorption

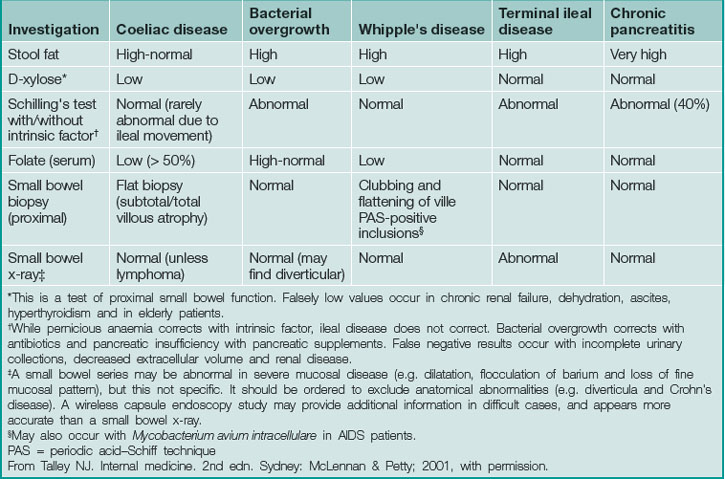

Diagnosis in malabsorption requires firstly suspecting its presence, secondly confirming its existence and thirdly demonstrating the cause (Table 14.2).

Confirming malabsorption

Breath tests

The triolein breath test for fat malabsorption involves the ingestion of 14C-labelled triolein and measures of 14CO2 in the expired air. Its lack of sensitivity has limited its clinical use.

Finding the cause of malabsorption

History

The list of causes of malabsorption (Box 14.2) is daunting, and a thorough history is essential to target investigations. Common causes of malabsorption include coeliac disease, chronic pancreatitis, small bowel bacterial overgrowth and gastric surgery.

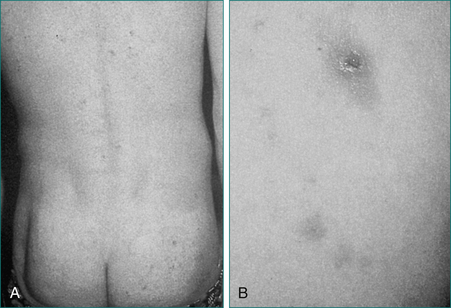

A cause may be obvious from the history if gastric surgery or a small bowel resection has been performed or there is known chronic pancreatitis. Childhood diarrhoea, failure to thrive or anaemia may suggest the possibility of coeliac disease. An associated skin rash of dermatitis herpetiformis (Fig 14.3) or a positive family history may also be clues to the diagnosis of coeliac disease.

Investigations

The nature and order of investigations carried out is dependent on the history. In many instances a cause will be suggested and investigations can be targeted. For example, upper abdominal pain may suggest pancreatitis, directing investigations towards demonstrating pancreatic disease. Crampy lower abdominal pain and diarrhoea would lead investigations towards exclusion of Crohn’s disease. Specific investigations are set out below.

In children with malabsorption, a sweat test is required to exclude cystic fibrosis.

Barium studies of the small bowel may define defects that give rise to malabsorption, such as strictures, diverticula or fistulae. Small bowel endoscopy or wireless capsule endoscopy can be useful in difficult cases.

Disorders that may Cause Chronic Diarrhoea or Malabsorption

Coeliac disease

Clinical features

Dermatitis herpetiformis (see Fig 14.3) presents with a pruritic papulovesicular rash on extensor surfaces of the limbs and also on the buttocks. Small bowel changes of coeliac disease are usual, but may be patchy. The condition responds to a gluten-free diet.

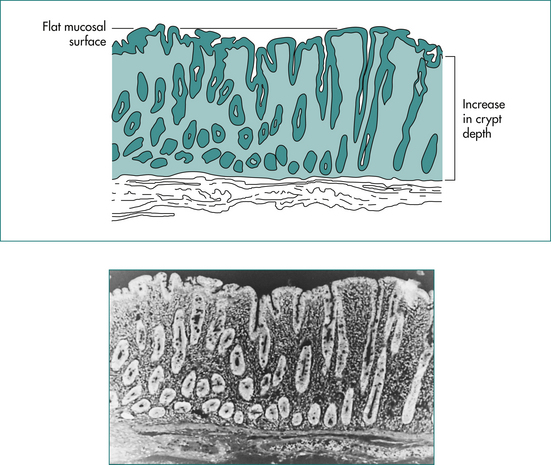

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of coeliac disease is made by documenting the typical mucosal changes (Fig 14.4) on small bowel biopsies, which are usually obtained at endoscopy. Multiple biopsies should be obtained from the second part of the duodenum. It is important to ensure that the patient is on a gluten diet before performing a biopsy, otherwise an adequate challenge of gluten (the equivalent of four slices of bread per day for 4–6 weeks) should be administered and the development of positive serology checked before performing a biopsy. Small bowel biopsies do, however, have their limitations (see Box 14.3).

Serological tests, useful for screening in coeliac disease are now available (Table 14.3). Tissue transglutaminase appears to be the target antigen detected by the endomysial antibody assay.

| Test | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| IgA AGA | 75–90 | 82–95 |

| IgG AGA | 69–85 | 73–90 |

| EMA | 85–90 | 97–100 |

| TGA | 93–96 | 99–100 |

AGA = antigliadin antibody; EMA = endomysial antibody; TGA = tissue transglutaminase antibody.

It is worth following first-degree relatives who share the HLA genotype but whose serology is negative and repeating the serology in 2 years. If the serology becomes positive a small bowel biopsy is indicated.

Whipple’s disease

Treatment with antibiotics has changed the course of the disease, resulting in recovery in most patients. Trimethoprim with sulfamethoxazole has replaced tetracycline as the antibiotic of choice due to the high relapse rate with tetracycline. Treatment needs to be prolonged.

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis is characterised by eosinophilic infiltration of the gut wall, often associated with peripheral blood eosinophilia.

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth

Causes of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth usually occurs with conditions causing small intestinal stasis. Those with impaired immunity and the elderly are also susceptible (Box 14.5).

Endocrine diseases

Key Points

D’Haens G., Baert F., van Assche G., et al. Early combined immunosuppression or conventional mangement in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease: an open randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371:660.

Dubinsky M.C. Azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine in inflammatory bowel disease: pharmacology, efficacy, and safety. Clin Gastroenterolgy Hepatol. 2004;2:731-743.

Duggan J.M. Coeliac disease: the great imitator. Med J Aust. 2004;180:524-526.

Headstrom P.D., Surawicz C.M. Chronic diarrhoea. Clinical Gastroenterology Hepatology. 2005;3:734-737.

Kagnoff M.F.A.G.A. Institute medical position statement on the diagnosis and management of coeliac disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(6):1977-1980.

Kucik C.J., Martin G.L., Sortor B.V. Common intestinal parasites. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1161-1168.

Mahnel R., Marth T. Progress, problems, and perspectives in diagnosis and treatment of Whipple’s disease. Clin Exp Med. 2004;3:39-43.

Pardi D.S. Microscopic colitis: an update. Inflammatory Bowel Dis. 2004;10:860-870.

Schiller L.R. Chronic diarrhea. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:287-293.

Walker M.M., Murray J.A., Ronkainen J., et al. Detection of celiac disease and lymphocytic enteropathy by parallel serology and histopathology in a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:112-119.