CHAPTER 58 CHRONIC DAILY HEADACHE

Chronic daily headache (CDH) of long duration is a clinical syndrome defined by headaches that occur for 4 hours a day or more on 15 days or more a month for more than 3 months.1,2 CDH is one of the most common and disabling headache presentations in headache specialty care centers; it afflicts 4% to 5% of the general population.3,4 Many patients with CDH are severely impaired.5 CDH sufferers also have higher disability than those with episodic migraine.6

As a syndrome, CDH was not included in the first or the second edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD).7,8 As a consequence, several separate proposals for its classification have emerged. Silberstein’s and Lipton’s criteria have been most widely used2 (unpublished data).

The S-L criteria divide primary CDH into transformed migraine, chronic tension-type headache (CTTH), new daily persistent headache (NDPH), and hemicrania continua and subclassify each of these into subtypes “with medication overuse” or “without medication overuse” (Table 58-1). Of these, only CTTH was included in the ICHD-I7 classification, whereas the ICHD-II8 has detailed diagnostic criteria for all four types of primary CDH of long duration. The term chronic migraine was introduced in place of transformed migraine and has a very different definition, as discussed later in this chapter. Although the ICHD-II is a vast improvement, recent studies show that it remains cumbersome for the classification of CDH in adults.9

TABLE 58-1 The Classification of the Chronic Daily Headaches* According to Silberstein’s and Lipton’s2 Criteria

* Daily or near-daily headache lasting ≥4 hours for ≥15 days/month.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF THE CHRONIC DAILY HEADACHE

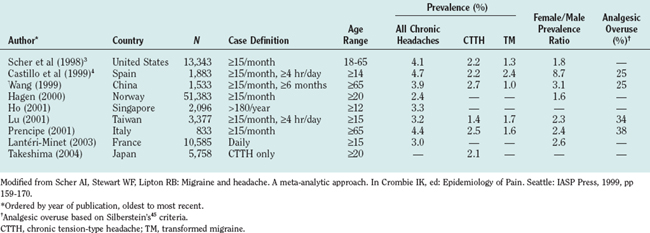

The epidemiology of CDH has been described in a number of population samples based in Europe, Asia, and the United States (Table 58-2).3,4,10,11 The prevalence of CDH is remarkably consistent among studies, ranging from 2.4% (Norway) to 4.7% (Spain). In the United States, the prevalence is 4.1%. From 35% to 50% of CDH sufferers in the population have transformed migraine.

TABLE 58-2 Prevalence of Very Frequent Headaches in Adult Populations According to Silberstein’s and Lipton’s2 Criteria

The incidence of CDH was investigated in a prospective study in the United States. Among subjects with episodic headaches at baseline, 3% developed CDH within 1 year.12 The incidence among migraine sufferers in subspecialty care is 13%.

Clinic-based studies show that CDH affects up to 80% of the patients presenting in a headache clinic.13–16 In this setting, transformed migraine is by far the most common type of CDH. In a study by Mathew and associates,14 77% of the patients with CDH had transformed migraine. In our clinic, transformed migraine represented 87.4% of the cases of CDH seen in a headache specialty center.13

CLINICAL CHARACTERIZATION

Transformed Migraine/Chronic Migraine

Patients with transformed migraine have a history of migraine. Sufferers usually report a process of transformation over months or years, and as headache frequency increases, associated symptoms become less severe and frequent.13–16 The process of transformation frequently ends in a pattern of daily or nearly daily headache that resembles CTTH, with some attacks of full migraine superimposed.2 In the clinical setting, migraine transformation is most often related to acute medication overuse, but transformation may occur without overuse.17 In the general population, most cases of transformed migraine are not related to medication overuse.12 Multiple risk factors may be involved in these cases (see section risk factors for the development of CDH).

The International Headache Society proposed criteria for the diagnosis of transformed migraine: (1) Headache frequency is 15 days or more per month for 3 months or more, with an average headache duration of more than 4 hours/day (if untreated); (2) the headache fulfills criteria for migraine without aura, on 8 or more of the headache days; and (3) the headache does not meet criteria for CTTH, hypnic headache, hemicrania continua, or NDPH (Table 58-3).

TABLE 58-3 Diagnostic Criteria for Primary Chronic Daily Headaches According to the International Classification of Headache Disorders (2004) Criteria and Silberstein’s and Lipton’s2 Criteria

| Headache | S-L–AHS | ICHD-II |

|---|---|---|

| Transformed migraine/chronic migraine |

Headache fulfilling HIS criteria for migraine without aura (1.1), migraine with aura (1.2), or probable migraine (1.6), on ≥50% of the headache days

|

ICHD-II, International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd ed.; IHS, International Headache Society; S-L, Silberstein and Lipton.

The terms transformed migraine and chronic migraine have been used synonymously in the past, but this is no longer appropriate: Chronic migraine has a specific definition in the ICHD-II, which does not recognize transformed migraine as a separate entity.8 One main difference exists between the S-L–AHS (transformed migraine) and ICHD-II (chronic migraine) systems: The ICHD-II criteria for chronic migraine require that headaches meeting criteria for migraine without aura occur on at least 15 days a month. To classify transformed migraine, the S-L–AHS criteria require at least 15 days of headache (not necessarily migraine), in which at least 50% of the days fulfill criteria for migraine or probable migraine.

Chronic Tension-Type Headache

CTTH (see Table 48-3) represents one half of the CDH cases found in population studies but just a small fraction of those found in specialty clinics. It is the only CDH that was addressed by the ICHD-I as a single diagnosis.7 The criteria remained little changed in the ICHD-II.8 Despite the International Headache Society criteria distinguishing between episodic headache and CTTH, this headache remains surprisingly poorly studied. This can be explained partially by the confusion between CTTH and transformed migraine with a low frequency of superimposed migraine attacks.

The prevalence of CTTH is markedly lower than that of episodic tension-type headache (ETTH), the most prevalent primary headache disorder. Its 1-year prevalence estimates range from 1.7% to 2.2%.18,19 The female preponderance of CTTH is greater than that of ETTH. In the United States, the prevalence of CTTH was reported to be 2.8 among women and 1.4 among men, with an overall gender prevalence ratio of 2.0.20 The prevalence of CTTH increases with age.

If the CDH develops abruptly (de novo), patients are said to have NDPH.

New Daily Persistent Headache

Daily headache (see Table 58-3) may begin without a history of evolution from episodic headache. Regardless of the phenotype, Silberstein’s and Lipton’s system classifies such headache as NDPH.2 NDPH is characterized by the relatively abrupt onset of an unremitting primary CDH in a patient without a previous headache syndrome. The new onset of this primary daily headache is the most important feature. The clinical features of the pain are not considered in making the diagnosis, which requires only the absence of a history of evolution from migraine or ETTH. Silberstein’s and Lipton’s classification allows the diagnosis of NDPH in patients with either migraine or ETTH if these disorders do not increase in frequency to give rise to NDPH.

The ICHD-II addresses NDPH as a single diagnosis in those with a new-onset CDH that resembles CTTH.8 A new-onset CDH with migrainous features cannot be classified as NDPH according to the ICHD-II criteria, whereas Silberstein and Lipton’s classification allows this diagnosis in patients with headache features of migraine or ETTH if the disorder arises abruptly.

Hemicrania Continua

Hemicrania continua (see Table 58-3) is an uncommon primary headache disorder first described as a syndrome by Sjaastad and Spierings.21 This daily, continuous, strictly unilateral headache is defined by its absolute response to therapeutic doses of indomethacin. Pain is moderate, with exacerbations of severe pain, and autonomic symptoms accompany these exacerbations, although less prominently than in cluster headache and chronic paroxysmal hemicrania.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Chronic Daily Headache as the Result of Progression of Disease

Although the source of pain in primary CDH is unknown and may be dependent on the subtype, research findings suggest that the following mechanisms, alone or in combination, contribute to the process:22 (1) abnormal excitation of peripheral nociceptive afferent fibers in the meninges; (2) enhanced responsiveness of trigeminal nucleus caudalis neurons; (3) decreased pain modulation from higher centers such as the periaqueductal gray matter; (4) spontaneous central pain generated by activation of the “on cells” in the medulla; (5) decreased serotonin levels; and (6) central sensitization.

There is evidence that a subgroup of migraine sufferers may have a clinically progressive disorder.23 Herein we analyze evidence that support the concept that migraine progresses within attacks and also as a disease, evolving to transformed migraine. Figure 58-1 summarizes theoretical concepts on this regard.

An imaging study has shown that iron deposition occurs in the periaqueductal gray area in subjects with chronic headaches.24 The periaqueductal gray area is related to the descending analgesic network and is important in controlling pain and providing endogenous analgesia. It is also closely related to the trigeminal nucleus. In this study, the iron levels were higher in migraine sufferers than in controls and higher in CDH headache sufferers than in migraineurs. These findings may be directly attributable to iron-catalyzed, free-radical cell damage. The authors suggested that iron deposition may reflect progressive neuronal damage related to recurrent migraine attacks. It can be hypothesized that repetitive central sensitization of the trigeminal neurons is correlated with iron deposition in the periaqueductal gray area and, therefore, migraine attacks predispose to disease progression.

Evidence of migraine progression also comes from a neuroimaging study.25 Kruit and colleagues used a cross-sectional design to study Dutch adults aged 30 to 60 years. They showed that male subjects who had migraine with aura were at an increased risk of posterior circulation infarction. In addition, women who had migraine with or without aura were at a higher risk of deep white matter lesions than were controls. The white matter lesions increased with attack frequency, possibly demonstrating progression of the disease.

Finally, in a longitudinal epidemiological study, Scher and associates12 showed that 3% of individuals with episodic headache (headache frequency, 2 to 104 days per year) progressed to CDH over the course of 1 year. The authors concluded that the incidence of CDH in subjects with episodic headache is 3% per year.

Burstein and colleagues26 showed that approximately 75% of migraine sufferers develop central sensitization (sensitization of the second order trigeminal neuron, which is clinically manifested by the development of cutaneous allodynia) during the course of a migraine attack. Central sensitization appears to be associated with triptan refractoriness. Central sensitization explains the progression of attacks but also may play a role in the progression of the disease itself. It is suggested that repeated central sensitization episodes are associated with permanent neuronal damage, preventive treatment refractoriness, and disease progression.26–28

Risk Factors for the Development of Chronic Daily Headache

Limited evidence exists about risk factors for migraine progression. One study revealed that the prevalence of CDH decreased slightly with age and increased in women (odds ratio, 1.65; 95% confidence interval, 1.3 to 2.0) and in divorced, separated, or widowed individuals (odds ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.2 to 1.9).11,12 CDH prevalence was inversely associated with educational level. Subjects with less than a high school education had more than a threefold risk of CDH in comparison with those with a graduate school–level education (odds ratio, 3.56; 95% confidence interval, 2.3 to 5.6). CDH was also associated with a self-reported physician’s diagnosis of arthritis (odds ratio, 2.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.9 to 3.3) or diabetes (odds ratio, 1.51; 95% confidence interval, 1.01 to 2.3), with previous head trauma, and with medication overuse.12

Of importance is that the risk of new-onset CDH increased nonlinearly with baseline headache frequency; elevated risk was limited primarily to controls with more than about two headaches per month. Finally, the stronger risk factor for the development of CDH was obesity (odds ratio, 5.53; 95% confidence interval, 1.4 to 21.8), a risk factor confirmed in another population study.29

Chronic Daily Headache and Medication Overuse

In most clinical studies of CDH, overuse of analgesics or other acute-care medications figures prominently.4,14,15,30 A number of issues with this association evoke controversy. Is overuse a significant factor in transforming episodic headache into CDH? Or is the frequently observed overuse merely a response to chronic pain itself? Although medication rebound has not been demonstrated in placebo-controlled trials, withdrawal headache has been shown in a controlled trial of caffeine withdrawal.31 Diener and Limmroth,32 using individual studies plus meta-analysis, found that the time required for the development of CDH was approximately 5 years of exposure to medication and a history of primary headache for 10 years before that. A patient develops CDH, according to Diener and Limmroth32 and Katsarava and colleagues,33 after consuming a critical dose of a single medication or a combination of medications for an extended period of time, which is shortest for triptans (1 to 2 years), longer for ergots (3 years), and longest for analgesics (5 years). Acute withdrawal of the offending medications worsens headache for a finite time, usually from 3 days to 3 weeks. Both preventive and acute-care treatments for the primary headache usually fail if use of the offending medication or medications is not terminated.34

In an attempt to better understand the relationship between medication overuse and refractory headaches, Wilkinson and coworkers35 looked for CDH in 28 patients who underwent total colectomy for ulcerative colitis. All migraineurs who overused opioids developed CDH (19%), whereas no nonmigraineurs who overused opioids did so. Bahra and associates36 showed that when nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are used daily in large doses for medical conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, they do not induce CDH in subjects without preexisting primary headache disorders. Both studies established two principles of medication overuse headache: (1) Even when the overused medication is used for reasons other than headache, it may still be associated with the development of CDH, and (2) acute medication overuse induces CDH only in those predisposed (i.e., those with preexisting episodic migraine).

THE TREATMENT OF CHRONIC DAILY HEADACHE

Principles of Treatment

As with other lifelong illness, several fundamental management considerations are important for treatment success in patients with CDH.37 Patients suffering from long-duration CDH often present not only with acute medication overuse but also with psychiatric and somatic comorbidity, low frustration tolerance, and physical and emotional dependence. In patients with primary CDH, it is important to identify the subtype of CDH and evaluate for the presence of analgesic overuse and comorbid conditions. A combination of pharmacological, nonpharmacological, behavioral, and sometimes physical interventions is usually necessary for a favorable outcome. The essential features of an effective treatment regimen include a combination of the following steps:

Treatment of Medication Overuse

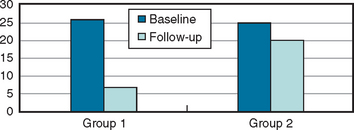

Most studies suggest the benefit and necessity of detoxifying the patient by weaning from the overused medication (when present), followed by an intensive, long-term treatment plan.38–40 Many patients who discontinue their overused medications experience considerable improvement; if they do not experience improvement, their condition is usually difficult to treat effectively. The evolution of the frequency of headache, in a comparison of patients who stopped using excessive analgesics with those who did not, as seen in a tertiary care setting after long-term follow-up, is displayed in Figure 58-1.41

A second adjunctive therapy is to use a short course of daily triptans in patients who are not overusing them. For example, a patient could use daily naratriptan (2.5 mg twice a day) for 7 days. One study showed that transitional therapy with naratriptan was as effective as transitional therapy with prednisone, and both were more effective than just tapering off the overused medication.42

For medications containing butalbital compounds or opioids, abrupt discontinuation may be followed by severe abstinence syndrome. Thereby, for patients suspected of overusing butalbital compounds, it is important to calculate the average daily dose of medication in order to slowly taper over time. One approach is to reduce the dosage by one tablet every 3 to 5 days. A more controlled approach is to replace the overused butalbital with longer-acting phenobarbital, from which it is easier to withdraw. For each 100-mg dose of butalbital, an equivalent dose would be 30 mg of phenobarbital in divided doses throughout the day. Once this switch has been made, phenobarbital can be tapered 15 to 30 mg/day, thereby avoiding withdrawal.37

For opioids, one approach is to taper the opioid 10% to 15% every day over 7 to 10 days. It usually helps to add clonidine, 0.05 or 0.1 mg two or three times a day, during opioid withdrawal. This prevents withdrawal symptoms (probably by decreasing the release of norepinephrine) and, if given in high enough doses, can speed the detoxification process. Clonidine can be given either by tablet or transcutaneously. During opioid withdrawal, lack of ability to fall and stay asleep may prevent appropriate medication reduction. Various sleep-promoting medications, including tricyclic antidepressants, atypical antipsychotics, tizanidine, benzodiazepines, and zolpidem, may help.37

Establishing an Effective Preventive Treatment

Most of the commonly used preventive agents for primary CDH have not been evaluated in well-designed double-blind studies. They are usually the same medications tried for migraine prevention. Table 58-4 summarizes the medications commonly used in CDH.

TABLE 58-4 Selected Preventive Therapies for Migraine That May Be Used in the Treatment of Chronic Daily Headache

| Generic Treatment | Dosage |

|---|---|

| α2 Agonists | |

| Clonidine tablets | 0.05 to 0.3 mg/day |

| Guanfacine tablets | 1 mg |

| Anticonvulsants | |

| Divalproex sodium tablets* | 500 to 1500 mg/day |

| Gabapentin tablets* | 300 to 3000 mg |

| Levetiracetam tablets | 1500 to 4500 mg |

| Topiramate tablets* | 50 to 200 mg |

| Zonisamide capsules | 100 to 400 mg |

| Antidepressants | |

| MAOIs | |

| Phenelzine tablets | 30 to 90 mg/day |

| TCA | |

| Amitriptyline tablets* | 30 to 150 mg |

| Nortriptyline tablets | 30 to 100 mg |

| SSRIs | |

| Fluoxetine tablets | 10 to 40 mg |

| Sertraline tablets | 25 to 100 mg |

| Paroxetine tablets | 10 to 30 mg |

| Venlafaxine tablets | 37.5 to 225 mg |

| Mirtazapine tablets | 15 to 45 mg |

| β Blockers | |

| Atenolol tablets* | 25 to 100 mg |

| Metoprolol tablets | 50 to 200 mg |

| Nadolol tablets | 20 to 200 mg |

| Propranolol tablets* | 30 to 240 mg |

| Timolol tablets* | 10 to 30 mg |

| Calcium Channel Antagonists | |

| Verapamil tablets* | 120 to 720 mg |

| Nimodipine tablets | 40 mg tid |

| Diltiazem tablets | 30 to 60 mg tid |

| Nisoldipine tablets | 10 to 40 mg qd |

| Amlodipine tablets | 2.5 to 10 mg qd |

| Serotonergic Agents | |

| Methysergide tablets* | 2 to 12 mg |

| Cyproheptadine tablets | 2 to 16 mg |

| Pizotifen tablets* | 1.5 to 3 mg |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Montelukast sodium tablets | 5 to 20 mg |

| Lisinopril tablets | 10 to 40 mg |

| Botulinum toxin A injection | 25 to 100 U (IM) |

| Feverfew tablets | 50 to 82 mg/day |

| Magnesium gluconate tablets | 400 to 600 mg/day |

| Riboflavin tablets | 400 mg/day |

| Petasites | 75 mg bid |

IM, intramuscularly; MAOI, monamine oxidase inhibitor; SSRI selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

* Evidence for moderate efficacy from at least two well-designed placebo-controlled trials.

The choice of a preventive drug is based on its proved efficacy, the patient’s preferences and headache profile, the drug’s side effects, and the presence or absence of coexisting or comorbid disease. The clinician should select the drug with the best risk/benefit ratio for the individual patient and minimize the side effects that are most important to the patient. Table 58-5 summarizes an assessment of the efficacy of, safety of, and evidence for a number of agents that may be useful in the preventive treatment of CDH.

TABLE 58-5 Choices of Preventive Treatment in Chronic Daily Headache

Rights were not granted to include this table in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book.

From Katsarava Z, Schneeweiss S, Kurth T, et al: Incidence and predictors for chronicity of headache in patients with episodic migraine. Neurology 2004; 62:788-790.

Prospects for Preventing Headache Progression

On the basis of the most recent data, some episodic headaches (migraine, ETTH) are now conceptualized not just as an episodic disorder but as a chronic episodic and sometimes chronic progressive disorder. Ongoing research and new emerging therapeutic strategies should account for this change in the conceptual model of migraine and CDHs. Preventing disease progression in migraine has already been added to the traditional goals of relieving pain and restoring patients’ ability to function. Emerging treatment strategies to prevent disease progression include risk factor modification, use of preventive therapies, and possibly the use of triptans as early as possible in the course of a migraine attack (Table 58-6).

TABLE 58-6 Risk Factors for Chronic Daily Headache Development and Srategies to Address Them

| Not Readily Modifiable |

| Sex: female |

| Low education/socioeconomic status |

| Head injury |

| Modifiable | Strategies to Address Modifiable Risk Factors |

|---|---|

| Attack frequency | Preventive treatment |

| Central sensitization | Early acute migraine interventions |

| Obesity | Diet |

| Using preventive medications that do not increase weight | |

| Medication overuse | Limiting the consumption of acute medications |

| Preventive treatment | |

| Detoxification protocols | |

| Stressful life events | Relaxation techniques |

| Biofeedback | |

| Addressing depression when present | |

| Snoring | Assessing sleep disturbances |

| Treating sleep apnea when present |

Bigal ME, Tepper SJ, Sheftell FD, et al. Chronic daily headache: correlation between the 2004 and the 1988 International Headache Society diagnostic criteria. Headache. 2004;44:684-691.

Katsarava Z, Schneeweiss S, Kurth T, et al. Incidence and predictors for chronicity of headache in patients with episodic migraine. Neurology. 2004;62:788-790.

Scher AI, Stewart WF, Liberman J, et al. Prevalence of frequent headache in a population sample. Headache. 1998;38:497-506.

Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Sliwinski M. Classification of daily and near-daily headaches: field trial of revised IHS criteria. Neurology. 1996;47:871-875.

Welch KM, Goadsby PJ. Chronic daily headache: nosology and pathophysiology. Curr Opin Neurol. 2002;15:287-295.

1 Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Solomon S, et al. Classification of daily and near-daily headaches: proposed revisions to the IHS criteria. Headache. 1994;34:1-7.

2 Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Sliwinski M. Classification of daily and near-daily headaches: field trial of revised IHS criteria. Neurology. 1996;47:871-875.

3 Scher AI, Stewart WF, Liberman J, et al. Prevalence of frequent headache in a population sample. Headache. 1998;38:497-506.

4 Castillo J, Muñoz P, Guitera V, et al. Epidemiology of chronic daily headache in the general population. Headache. 1999;39:190-196.

5 Spierings ELH, Ranke AH, Schroevers M, et al. Chronic daily headache: a time perspective. Headache. 2000;40:306-310.

6 Bigal ME, Rapoport AM, Lipton RB, et al. Assessment of migraine disability using the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire: a comparison of chronic migraine with episodic migraine. Headache. 2003;43:336-342.

7 Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgia, and facial pain. Cephalalgia. 1988;8(Suppl 7):1-96.

8 Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias, and facial pain. Second Edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(Suppl 1):1-160.

9 Bigal ME, Tepper SJ, Sheftell FD, et al. Chronic daily headache: correlation between the 2004 and the 1988 International Headache Society diagnostic criteria. Headache. 2004;44:684-691.

10 Silberstein SD, Dodick D, Lipton RB, et al: Classifying migraine patients with primary chronic daily headache. Consensus statement from the American Headache Society. Headache. In press.

11 Scher AI, Stewart WF, Lipton RB. Caffeine as a risk factor for chronic daily headache: a population-based study. Neurology. 2004;63:2022-2027.

12 Scher AI, Stewart WF, Ricci JA, et al. Factors associated with the onset and remission of chronic daily headache in a population-based study. Pain. 2003;106(1–2):81-89.

13 Bigal ME, Sheftell FD, Rapoport AM, et al. Chronic daily headache in a tertiary care population: correlation between the International Headache Society diagnostic criteria and proposed revisions of criteria for chronic daily headache. Cephalalgia. 2002;22:432-438.

14 Mathew NT, Reuveni U, Perez F. Transformed or evolutive migraine. Headache. 1987;27:102-106.

15 Spierings EL, Schroevers M, Honkoop PC, et al. Presentation of chronic daily headache: a clinical study. Headache. 1998;38:191-196.

16 Mathew NT. Transformed migraine. Cephalalgia. 1993;13(Suppl 12):78-83.

17 Bigal ME, Sheftell FD, Rapoport AM, et al. Chronic daily headache: identification of factors associated with induction and transformation. Headache. 2002;42:575-581.

18 Rasmussen BK, Olesen J. Epidemiology of migraine and tension-type headache. Curr Opin Neurol. 1994;7:264-271.

19 Lavados PM, Tenhamm E. Epidemiology of tension-type headache in Santiago, Chile: a prevalence study. Cephalalgia. 1998;18:552-558.

20 Schwartz BS, Stewart WF, Simon D, et al. Epidemiology of tension-type headache. JAMA. 1998;4:381-383. 279

21 Sjaastad O, Spierings EL. “Hemicrania continua:” another headache absolutely responsive to indomethacin. Cephalalgia. 1984;4:65-70.

22 Welch KM, Goadsby PJ. Chronic daily headache: nosology and pathophysiology. Curr Opin Neurol. 2002;15:287-295.

23 Scher AI, Lipton RB, Stewart W. Risk factors for chronic daily headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2002;6:486-491.

24 Welch KMA, Nagesh V, Aurora SK, et al. Periaqueductal gray matter dysfunction in migraine: cause or the burden of illness? Headache. 2001;41:629-637.

25 Kruit MC, van Buchem MA, Hofman PA, et al. Migraine as a risk factor for subclinical brain lesions. JAMA. 2004;291:427-434.

26 Burstein R, Yarnitsky D, Goor-Aryeh I, et al. An association between migraine and cutaneous allodynia. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:614-624.

27 Burstein R, Jakubowski M. Analgesic triptan action in an animal model of intracranial pain: a race against the development of central sensitization. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:27-36.

28 Yarnitsky D, Goor-Aryeh I, Bajwa ZH, et al. 2003 Wolff Award Presentation: possible parasympathetic contributions to peripheral and central sensitization during migraine. Headache. 2003;43:704-714.

29 Bigal M, Liberman M, Lipton R. Body mass index and headache: associations with attack frequency, severity and disability. Neurology. 2005;61(Suppl 1):421-422.

30 Katsarava Z, Schneeweiss S, Kurth T, et al. Incidence and predictors for chronicity of headache in patients with episodic migraine. Neurology. 2004;62:788-790.

31 Silverman K, Evans SM, Strain EC, et al. Withdrawal syndrome after the double-blind cessation of the caffeine consumption. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1109-1114.

32 Diener HC, Limmroth V. Medication-overuse headache: a worldwide problem. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:475-483.

33 Katsarava Z, Fritsche G, Muessig M, et al. Clinical features of withdrawal headache following overuse of triptans and other headache drugs. Neurology. 2001;57:1694-1698.

34 Rapoport A, Stang P, Gutterman DL, et al. Analgesic rebound headache in clinical practice: data from a physician survey. Headache. 1996;36:14-19.

35 Wilkinson SM, Becker WJ, Heine JA. Opioid use to control bowel motility may induce chronic daily headache in patients with migraine. Headache. 2001;41:303-309.

36 Bahra A, Walsh M, Menon S, et al. Does chronic daily headache arise de novo in association with regular use of analgesics? Headache. 2003;43:179-190.

37 Tepper SJ, Rapoport AM, Sheftell FD, et al. Chronic daily headache—an update. Headache Care. 2004;1:233-245.

38 Krymchantowski AV. Overuse of symptomatic medications among chronic (transformed) migraine patients: profile of drug consumption. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2003;61:43-47.

39 Grazzi L, Andrasik F, D’Amico D, et al. Behavioral and pharmacologic treatment of transformed migraine with analgesic overuse: outcome at 3 years. Headache. 2002;42:483-490.

40 Diener HC, Haab H, Peters C, et al. Subcutaneous sumatriptan in the treatment of headache during withdrawal from drug-induced headache. Headache. 1991;31:205-209.

41 Bigal ME, Rapoport AM, Sheftell FD, et al. Transformed migraine and medication overuse in a tertiary headache centre—clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:483-490.

42 Krymchantowski AV, Moreira PF. Outpatient detoxification in chronic migraine: comparison of strategies. Cephalalgia. 2003;23:982-993.