100 Chronic bronchitis

Salient features

Examination

• From the end of the bed: for obvious breathlessness, pursed lip breathing and symmetrical chest movements—and count respiratory rate.

• Look for nail changes such as tar staining.

• Feel the palms for warmth and the pulse for rapid bounding pulse (signs of carbon dioxide retention).

• Comment on the active contractions of the accessory muscles of respiration such as sternocleidomastoids, scaleni and trapezii.

• Palpate for tracheal deviation and measure the distance between the cricoid cartilage and suprasternal notch (less than three fingers’ breadth in emphysema).

• Comment on barrel-shaped chest

• Inspiratory retraction of the lower ribs (Hoover’s sign)

Questions

Advanced-level questions

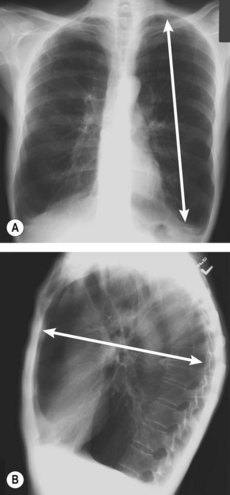

What is explanation for the cardiac silhouette on chest radiography in patients with emphysema?

In patients with emphysema, the cardiac silhouette on chest radiography is typically long and narrow (Fig. 100.1). The common explanation for this finding is the altered, more vertical position of the heart in the thoracic cavity. A recent study suggested an alternative explanation for this finding: a decreased left ventricular volume (N Engl J Med 2010;362:217). This study also reported a linear relation to impaired left ventricular filling, reduced stroke volume and lower cardiac output without changes in the ejection fraction.

How would you differentiate emphysema from chronic bronchitis?

| Predominant bronchitis | Predominant emphysema | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40–45 | 50–75 |

| Appearance | Blue bloater | Pink puffer |

| Dyspnoea | Mild; late | Severe; early |

| Cough | Early; copious sputum | Late; scanty sputum |

| Infections | Common | Occasional |

| Respiratory insufficiency | Repeated | Terminal |

| Cor pulmonale | Common | Rare; terminal |

| Airway resistance | Increased | Normal or slightly increased |

| Elastic recoil | Normal | Low |

| Chest radiograph | Prominent vessels; large heart | Hyperinflation; small heart |

From Kumar et al. Pathologic Basis of Disease, 8th edn. Saunders.

If the patient was between the ages of 30 and 45 years, what would you consider to be the underlying cause of the emphysema?

What medications are commonly used in outpatient treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?

How would you treat an acute exacerbation?

• Nebulized bronchodilators: terbutaline, ipratropium bromide

• Intravenous antibiotics (BMJ 1994;308:871–872), initially with amoxicillin and, if no clinical response, then with a second-generation cephalosporin, quinoline or co-amoxiclav. Antibiotics decrease the relative risk of treatment failure by approximately 50% in exacerbations (Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;2:CD004403)

• Intravenous hydrocortisone and oral steroids (steroids useful in only acute exacerbations and, unlike in asthma, do not influence the course of chronic bronchitis). Systemic steroids reduced the relative risk of treatment failure (as defined by intensification of therapy, rehospitalization or return to the emergency department) by about 30% in patients with acute exacerbations who were hospitalized or seen in the emergency department (N Engl J Med 1999;340:1941–7; N Engl J Med 2003;348:2618–25).

What are the organisms commonly associated with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?

What clinical features would suggest that this patient is suitable for long-term domiciliary oxygen therapy?

• COPD: FEV1 <1500 ml, FVC <2000 ml and stable chronic respiratory failure (Pao <7.3 kPa, that is, 55 mmHg or oxygen saturation <88% at normal blood pH) in patients who have (1) had peripheral oedema or (2) not necessarily had hypercapnia or oedema (New Engl J Med 1995;333:710–14); carboxyhaemoglobin of <3% (i.e. patients who have stopped smoking)

• Terminally ill patients of whatever cause with severe hypoxia (Pao <7.3 kPa).

What do you know about the BODE index?

What do you know about molecular genetics of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?

Deficiency of α1-antitrypsin

• It was first described in Sweden. The patient is deficient in α1-antitrypsin, with activity approximately 15% of normal values; concentrations of 40% or more are required for health. The patient is homozygous for the gene (Z) encoding a protease inhibitor (Pi). Other genetic combinations and their percentage normal activity are MS (80%), MZ (60%), SS (60%), SZ (40%). Six per cent of the population is heterozygous for S(PiMS) and 4% for Z(PiMZ), making an overall frequency of 1 in 10 for the carriage of the defective gene. Liver transplantation results in conversion to the genotype of the donor.

• In the lung α1-antitrypsin inhibits the excessive actions of neutrophil and macrophage elastase, which cigarette smoke promotes. When the lung is heavily exposed to cigarette smoke, the protective effect of α1-antitrypsin may be overwhelmed by the amount of elastase released or by a direct oxidative action of cigarette smoke on the α1-antitrypsin molecule. The emphysema is panacinar and is seen in the lower lobes of the lungs. Smoking increases the severity of, and decreases the age of onset of, emphysema. Liver disease is a much less common complication. Human α1-antitrypsin prepared from pooled plasma from normal donors is recommended for patients over 18 years with serum levels below 11 µmol/l and abnormal lung function.

• The siblings of an index case should be screened for this disorder. Their identification should be followed by counselling to avoid smoking and occupations with atmospheric pollution. Children of homozygotes will inherit at least one Z gene and hence will be heterozygotes. They should avoid pairing with another heterozygote if they wish to avoid the risk of producing an affected homozygote.

What is the role of surgery in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?

• Bullectomy may improve gas exchange and airflow, and reduce dyspnoea in selected patients with bullae larger than one-third of the hemithorax and accompanying lung compression.

• Lung-volume reduction surgery (N Engl J Med 2000;343:239–45) results in functional improvements including increased FEV1, reduced total lung capacity, improved function of respiratory muscles, improved exercise capacity and improved quality of life (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1999;112:1319–29, Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160:2018–27). The National Emphysema Treatment Trial Group found that lung-volume reduction surgery increased the chance of improved exercise capacity but did not confer a survival advantage over medical therapy. It did yield a survival advantage for patients with both predominantly upper-lobe emphysema and low baseline exercise capacity. Patients previously reported to be at high risk and those with non-upper-lobe emphysema and high baseline exercise capacity are poor candidates for lung-volume reduction surgery because of increased mortality and negligible functional gain (N Engl J Med 2003;348:2059–73).

• Single lung transplantation has been successful for at least 3–4 years in patients with COPD. The criteria for selecting patients for transplantation have not been established. It does not improve survival but improved quality of life (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1991;101:623–32, J Heart Lung Transplantation 2006;25:75–84).

Mention some newer treatments for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

• Antagonists of inflammatory mediators: 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors, leukotriene B4 antagonists, interleukin-8 antagonists, tumour necrosis factor inhibitors and antioxidants

• Protease inhibitors: neutrophil elastase inhibitors, cathepsin inhibitors, non-selective matrix metalloprotease inhibitors, elafin, secretory leukoprotease inhibitor, α1-antitrypsin

• New anti-inflammatory agents: phosphodieasterase-4 inhibitors, nuclear factor-κB inhibitors, adhesion molecule inhibitors and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitors (N Engl J Med 2000;343:1960–1).

American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS). Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of COPD. www.ersnet.org.

Cochrane Airways Group (up-to-date, accurate systematic reviews and meta-analyses). www.cochrane-airways.ac.uk.

United Kingdom National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). COPD guidelines. www.nice.org.uk.

World Health Organization Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) resources. www.goldcopd.com.

Peter Barnes, contemporary physician and professor, National Heart and Lung Institute London.

Sir Michael Rawlins is the founding chairman of National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). From 1973 to 2006, Rawlins was the Ruth and Lionel Jacobson Professor of Clinical Pharmacology University of Newcastle. Rawlins obtained his medical degree at St Thomas’ Hospital. His post-graduate training in clinical pharmacology and general medicine was completed at St Thomas’ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hammersmith_Hospital” \o “Hammersmith Hospital” Hammersmith hospitals, with a year at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.