CHAPTER 11 Chronic Abdominal Pain

The evaluation of any patient with a complaint of abdominal pain is challenging. Abdominal pain can be benign and self-limited or a harbinger of a serious life-threatening disease (see Chapter 10). Chronic abdominal pain poses a particularly challenging clinical problem. Not only is the management of chronic abdominal pain a frequently daunting task, but also the possibility of overlooking a structural or organic disorder is always a concern. Many disorders discussed elsewhere in this text can produce chronic abdominal pain (Table 11-1). Many of these diagnoses require careful consideration and clinical interrogation, in addition to appropriate diagnostic testing, to discern whether the entity is indeed the cause of the patient’s pain. Diagnosis of a functional gastrointestinal disorder is generally considered once potential causes of organic chronic abdominal pain have been confidently excluded. Although the causes of chronic abdominal pain are varied, the pathophysiologic pathways that produce chronic pain are common to many of them. This chapter focuses on the neuromuscular causes of chronic abdominal pain and the functional abdominal pain syndrome (FAPS). FAPS serves as a model to illustrate many of the complex issues involved in caring for patients with chronic abdominal pain.

Table 11-1 Differential Diagnosis of Chronic or Recurrent Abdominal Pain

| Structural (or Organic) Disorders |

| Inflammatory |

| Vascular |

| Metabolic |

| Neuromuscular |

| Other |

| Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders |

DEFINITION AND CLINICAL APPROACH

As for acute abdominal pain (see Chapter 10), the initial step in evaluating a patient with chronic abdominal pain is to elicit a detailed history from the patient. The chronology of the pain, including its abruptness of onset and duration, and its location and possible radiation should be determined. Visceral pain emanating from the digestive tract is perceived in the midline, because of the relatively symmetrical bilateral innervation of the organs, but is diffuse and poorly localized.1 Referred pain is ordinarily located in the cutaneous dermatomes that share the same spinal cord level as the affected visceral inputs.2 The patient should be questioned about the intensity and character of the pain, with the understanding that these parameters are subjective. The patient’s perception of precipitating, exacerbating, or mitigating factors may be useful when diagnostic possibilities are considered.

A complete physical examination is indicated to look for evidence of a systemic disease. The abdominal examination should use a combination of inspection, auscultation, percussion, and palpation. The most critical step for a patient with an acute exacerbation of chronic abdominal pain is to ascertain promptly whether a surgical abdomen is present (see Chapter 10). Although most causes of chronic abdominal pain do not require immediate surgical treatment, a complication related to a disease process ordinarily associated with chronic abdominal pain may present acutely (e.g., intestinal perforation in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease). Furthermore, a patient who has experienced chronic abdominal pain may present with acute pain related to another disease process (e.g., acute mesenteric ischemia in a patient with underlying irritable bowel syndrome [IBS]). The abdomen should be auscultated to detect an abdominal bruit, because the presence of a bruit may suggest chronic mesenteric ischemia (intestinal angina). Abdominal palpation for the presence of organomegaly, masses, and ascites and examination for hernias are particularly pertinent. Other physical findings that suggest an underlying organic illness include signs of malnutrition (e.g., muscle wasting or edema), vitamin deficiencies, or extraintestinal processes (e.g., arthropathy or skin changes). Although not entirely specific, the closed eyes sign is often seen in patients with FAPS (see later). Similarly, Carnett’s sign and the hover sign (described later) may be seen in persons with abdominal wall pain.

ABDOMINAL WALL PAIN

ANTERIOR CUTANEOUS NERVE ENTRAPMENT AND MYOFASCIAL PAIN SYNDROMES

Although ACNES was initially described in the 1970s, it remains a frequently overlooked cause of chronic abdominal pain.3,4 In ACNES, the pain is believed to occur when there is entrapment of a cutaneous branch of a sensory nerve that is derived from a neurovascular bundle emanating from spinal levels T7 to T12. The nerve entrapment may be related to pressure from an intra- or extra-abdominal lesion or to another localized process, such as fibrosis or edema. Pain emanating from the abdominal wall is discrete and localized, in contrast to pain originating from an intra-abdominal source, which is diffuse and poorly localized. Patients usually point to the location of their pain with one finger, and the examiner can often localize the area of maximal tenderness to a region less than 2 cm in diameter. During physical examination, the patient often guards the affected area from the examiner’s hands (hover sign).5 Patients often note that activities associated with tightening of the abdominal musculature are associated with an exacerbation of pain and, during physical examination, the clinician will note increased localized tenderness to palpation when the patient tenses the abdominal muscles (Carnett’s sign).6 In contrast, an increase in tenderness during relaxation of the abdominal musculature suggests an intra-abdominal source of pain.

In MFPS, pain emanates from myofascial trigger points in skeletal muscle.7 Causative factors include musculoskeletal trauma, vertebral column disease, intervertebral disc disease, osteoarthritis, overuse, psychological distress, and relative immobility. The exact pathophysiology of pain in MFPS remains unclear. Chronic abdominal wall pain may occur in patients with MFPS. Pain may be referred from another site, and the identification of trigger points (including those remote from the site of pain) is a useful physical finding. When attempting to identify a trigger point, the examiner uses a single finger to palpate a tender area. This is most often located in the central portion of a muscle belly, which may feel indurated or taut to palpation, and elicits a jump sign.8 This finding refers to a patient’s response by wincing, jerking away, or crying out as the myofascial trigger point is detected. Less commonly, trigger points may be located at sites such as the xiphoid process, costochondral junctions, or ligamentous and tendinous insertions.

Treatment of ACNES and MFPS, when successful, not only improves symptoms, but also confirms the diagnosis.9,10 The treatment strategy depends on the severity of the symptoms. With mild and intermittent symptoms that are reproducibly precipitated by certain movements, simple reassurance and a recommendation to avoid such movements may suffice. Non-narcotic analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and application of heat can be used during exacerbations. Physical therapy may be beneficial, although no randomized studies have supported this treatment modality. For severe and persistent symptoms, injection therapy with a local anesthetic, with or without a glucocorticoid, is recommended.9–11 In one study of 136 patients in whom the history and physical examination suggested abdominal wall pain, and in whom benefit was noted with injection therapy, the diagnosis remained unchanged after a mean follow-up of four years in 97% of cases.12 In carefully selected patients with symptoms refractory to injection therapy, a prospective nonrandomized investigation has suggested that diagnostic laparoscopy with open exploration of abdominal trigger points may be beneficial.13 In this study, after intra-abdominal adhesions in close proximity to trigger points were lysed, subcutaneous nerve resection was performed. After a median postoperative follow-up of 37 months, 23 of 24 patients (96%) believed that this approach was beneficial in managing their previously intractable pain.

SLIPPING RIB SYNDROME

The slipping rib syndrome (SRS), which was described initially in the early 20th century,14,15 is an uncommonly recognized cause of chronic lower chest and upper abdominal pain. SRS ordinarily causes unilateral, sharp, often lancinating pain in the subcostal region. The acute pain may be followed by a more protracted aching sensation. The syndrome is associated with hypermobility of the costal cartilage at the anterior end of a false rib (rib 8, 9, or 10), with slipping of the affected rib behind the superior adjacent rib during contraction of the abdominal musculature. This slipping causes pain by a variety of potential mechanisms, including costal nerve impingement and localized tissue inflammation. The key to diagnosis is clinical awareness of the syndrome, in conjunction with use of the hooking maneuver; the clinician hooks his or her examining fingers underneath the patient’s lowest rib and, as the rib is moved anteriorly, the pain is reproduced and an audible pop or click is often heard.16 Conservative therapeutic measures often suffice but, on occasion, costochondral nerve blockade, response to which supports the diagnosis, or even surgical rib resection is required.17

THORACIC NERVE RADICULOPATHY

Disease related to thoracic nerve roots T7 through T12 may be responsible for abdominal pain. The disease processes that may cause this problem include neuropathy related to back and spine disorders, diabetes mellitus, and herpes zoster infection.18,19 Obtaining a complete history and performing a careful physical examination of the patient, with attention to the possibility of a systemic disease and abnormal neurologic and dermatologic findings, should lead to the correct diagnosis in most instances. Treatment depends on the specific underlying disease process.

FUNCTIONAL ABDOMINAL PAIN SYNDROME

FAPS is a distinct medical disorder. Evidence suggests that the syndrome relates to central nervous system (CNS) amplification of normal regulatory visceral signals, rather than functional abnormalities in the gastrointestinal tract.20,21 The disorder is characterized by continuous, almost continuous, or at least frequently recurrent abdominal pain that is poorly related to bowel habits and often not well localized. FAPS is properly understood as abnormal perception of normal (regulatory) bowel function rather than a motility disorder. The syndrome appears to be closely related to alterations in endogenous pain modulation systems, including dysfunction of descending and cortical pain modulation circuits.21 The Rome III diagnostic criteria for FAPS are shown in Table 11-2.20,21 Studies that included patients who meet diagnostic criteria for FAPS have revealed that only rarely is an organic cause of chronic abdominal pain found during long-term follow-up.22,23

Table 11-2 Rome III Criteria for Functional Abdominal Pain Syndrome*

| Must include all the following: |

* Criteria fulfilled for the past three months with symptom onset at least six months prior to diagnosis.

FAPS is commonly associated with other unpleasant somatic symptoms, and, when it persists or dominates the patient’s life, it usually is associated with chronic pain behaviors and comorbid psychological disturbances.24 Patients with FAPS typically define their illness as medical, and their symptoms tend to be more severe and associated with greater functional impairment than those of patients with IBS.24 Psychological disturbances, if present, must be considered as comorbid features of FAPS rather than as part of a primarily psychiatric problem.25 When compared with patients who have chronic back pain, those with chronic abdominal pain report significantly better physical functioning, yet their overall perception of health is significantly worse.26

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Although the epidemiology of FAPS is incompletely known, in the U.S. Householder Survey of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, FAPS was estimated to be present in 2% of the sample and was less frequent than IBS (9%).27 A female predominance was noted (F:M = 1.5). Patients with FAPS missed more work days because of illness and had more physician visits than those without abdominal symptoms. A substantial proportion of patients are referred to gastroenterology practices and medical centers; they have a disproportionate number of health care visits and often undergo numerous diagnostic procedures and treatments.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

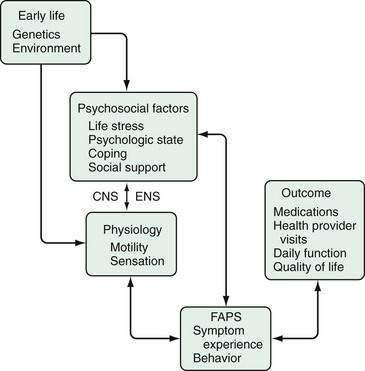

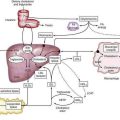

Chronic pain is a multidimensional (sensory, emotional, cognitive) experience explained by abnormalities in neurophysiologic functioning at the afferent, spinal, and CNS levels. Unlike acute pain arising from peripheral or visceral injury or disease, chronic functional pain is not associated with increased afferent visceral stimuli from structural abnormalities and tissue damage. FAPS is considered what is termed a biopsychosocial disorder related to dysfunction of the brain-gut axis (see Chapter 21).25 As shown in Figure 11-1, the clinical expression of FAPS is derived from psychological and intestinal physiologic input that interacts via the CNS-gut neuraxis. This model integrates the clinical, physiologic, and psychosocial features of FAPS into a comprehensible form, providing the basis for understanding psychological influences and application of psychopharmacologic treatments.

Research relating to the pathophysiology of painful functional gastrointestinal disorders has focused on the concepts of visceral hypersensitivity and alterations of brain-gut interactions. Visceral hypersensitivity is facilitated by up-regulation of mucosal nociceptors and sensitization of visceral afferent nerves.28 Dysregulation of the brain-gut axis can be manifested as central enhancement of afferent visceral signals.29 The brain-gut dysregulation can, in turn, be initiated or modified by a variety of events. In a large-scale, prospective, controlled investigation of the development of chronic abdominal pain in women undergoing gynecologic surgery for nonpainful indications, pain developed significantly more frequently in the surgical group (15%) than in a nonsurgical control group (4%). The development of chronic abdominal pain in the postoperative setting was predicted only by psychosocial, and not surgical, variables, implying that the development of pain is associated closely with central registration and amplification of the afferent signal. This study lends strong support to the biopsychosocial model, documenting the importance of cognitive and emotional input during the development of postoperative FAPS.

Ascending Visceral Pain Transmission

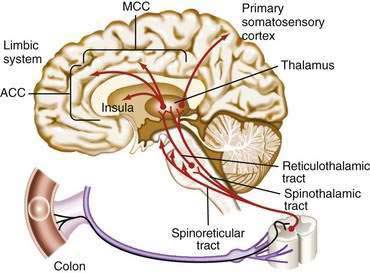

The afferent transmission of visceral abdominal pain involves first-order neurons that innervate the viscera, carry information to the thoracolumbar sympathetic nervous system, and subsequently synapse in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Second-order neurons cross and ascend from the dorsal horn via the spinothalamic and spinoreticular tracts. These second-order neurons synapse in the thalamus with third-order neurons that synapse with the somatosensory cortex (sensory-discriminative component), which is involved in the somatotypic or point-specific localization and intensity of afferent signals, and with the limbic system (motivational-affective component), which contains the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC; Fig. 11-2; see also Chapter 21). The insular cortex receives input from the sensory thalamus and the nucleus tractus solitarius and integrates visceral sensory and emotional information.31 The limbic system serves as a modulator of the pain experience, based on the individual’s emotional state, prior experiences, and cognitive interpretation of the signal. This multicomponent integration of nociceptive information in the CNS explains the variability in the experience and reporting of pain.32 Motivational-affective regions of the CNS are important contributors to the chronic pain experience by modulating afferent sensory information from the intestine.

This conceptual scheme of pain modulation has been demonstrated through PET imaging with the use of radiolabeled oxygen.33 In a group of healthy subjects who immersed their hands in hot water, half were hypnotized to experience the immersion as painful and the other half as not painful or even pleasant. The changes in cortical activation were compared between the two groups, and no difference was found in activity in the somatosensory cortex; however, those who experienced pain had significantly greater activation of the ACC of the limbic system, which is involved in the affective component of the pain experience. Functional brain imaging studies comparing patients with functional gastrointestinal disease and normal controls have shown abnormal brain activation mainly in the motivational-affective pain regions, including the prefrontal cortex, ACC, amygdala, and insula.34 These regions generally show increased activation in patients with chronic pain, thereby suggesting abnormal afferent input as well as central modulation, which could be caused in part by increased attention to visceral stimuli, abnormal cognitive or affective processing of afferent input, or comorbid psychiatric disorders.

Descending Modulation of Pain

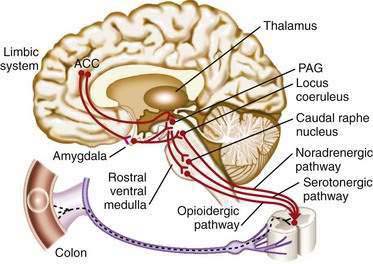

According to the gate control theory, afferent transmission of visceral pain can be modulated by descending impulses from the cortex down to the visceral nerves.32 In this model, the central descending control of the gating system occurs primarily through the descending inhibitory system.35 This system is an endorphin- or enkephalin-based neural network that originates from the cortex and limbic system and descends to the spinal cord, with major links in the midbrain (periaqueductal gray) and medulla (caudal raphe nucleus; Fig. 11-3). This system inhibits nociceptive projection directly on the second-order neurons or indirectly via inhibitory interneurons in the spinal cord. Then, the dorsal horn of the spinal cord acts as a gate to modulate (i.e., increase or decrease) transmission of afferent impulses from peripheral nociceptive sites to the CNS. In effect, this descending pain modulation system determines the amount of peripheral afferent input from the gut that is allowed to ascend to the brain. Descending inhibitory systems can be diffuse and, when activated, inhibit pain sensitivity throughout the body—so-called diffuse noxious inhibitory control (DNIC). Patients with chronic pain syndromes, including FAPS, appear to have an impaired ability to activate DNIC.36

Visceral Sensitization

Recurrent peripheral stimulation is thought to up-regulate afferent signals or inhibit descending pain control mechanisms, thereby sensitizing the bowel and producing a state of visceral hyperalgesia (increased pain response to a noxious signal) and chronic pain. Several clinical studies have supported this concept, and the increase in pain appears to occur to a greater degree in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders than in healthy subjects.37 Furthermore, preoperative treatment with local or regional anesthesia or NSAIDs reduces the severity of postoperative pain,38 suggesting that the CNS response to peripheral injury can be modified by prior reduction of afferent input to the spinal cord and CNS. Conversely, recurrent peripheral injury, such as repeated abdominal operations, may sensitize intestinal receptors, thereby making perception of even baseline afferent activity more painful (allodynia). Visceral sensitization may develop through different mechanisms at one or more levels of the neuraxis, including the mucosal level (via afferent silent nociceptors) and spinal level (spinal hyperexcitability). Patients with IBS may also experience hyperalgesia. Studies of rectal balloon distention in patients with IBS have demonstrated that a greater proportion of patients report discomfort to balloon distention than normal volunteers at a given volume of inflation; in addition, the intensity of the discomfort in patients is higher than in the normal volunteers.39 Rectal hypersensitivity induced by repetitive painful rectal distention is seen in patients with IBS, but not FAPS.40 This observation supports the contention that IBS and FAPS are distinct functional gastrointestinal disorders.

Biochemical Mechanisms of Sensitization

The biochemical basis of visceral sensitization is under active study, and this research may identify future targets for therapy. Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]) has received considerable attention because the gastrointestinal tract is its main source within the body.41 5-HT is found primarily in mucosal enterochromaffin cells, where it appears to serve as a neurotransmitter of the enteric nervous system (ENS) and as a paracrine molecule that signals other (e.g., vagal) neural activity. 5-HT mediates numerous gastrointestinal functions, and modulation of various receptor subtypes, such as 5-HT1, 5-HT3, and 5-HT4, and of 5-HT reuptake affects gastrointestinal sensorimotor function.

Role of the Central Nervous System

Although peripheral sensitization may influence the onset of pain, the CNS is critically involved in the predisposition to and perpetuation of chronic pain. In FAPS, the preeminent role of the CNS is evident by the lack of peripheral motor or sensory abnormalities and the strong association with psychosocial disturbances. In addition, comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, major life stressors, a history of sexual or physical abuse, poor social support, and maladaptive coping all are associated with more severe chronic abdominal pain and poorer health outcomes.31,42,43 These factors in patients with FAPS and other functional gastrointestinal pain conditions may impair or diminish descending inhibitory pain pathways that act on dorsal horn neurons or may amplify visceral afferent signals.25,36,44 Prospective studies of patients with postinfection IBS (see Chapter 118) and postoperative FAPS support the importance of the brain in the experience of gastrointestinal pain.30,45

Functional brain imaging has been useful in clarifying brain-gut interaction and has demonstrated that links between emotional distress and chronic pain may be mediated through impairment in the ability of the limbic system to modulate visceral signals. The motivational-affective component of the central pain system, specifically the ACC (see Figs. 11-2 and 11-3), is dysfunctional in patients with IBS and other chronic painful conditions. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and PET brain imaging in response to rectal distention in patients with IBS have shown differential activation of the ACC in patients compared with normal subjects46 and increased activation of the thalamus.46,47 Similar results have been found in patients with a history of abuse, somatization, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Furthermore, the return of ACC activity to baseline in depressed patients is associated with clinical improvement48 and predicts response to antidepressant treatment.49 As the pain and emotional distress of a patient with IBS improve, the activity within the ACC changes correspondingly.50 A study of patients with IBS and an abuse history used functional brain MRI to show that during aversive visceral stimulation (rectal balloon distention), differential activation of regions of the ACC occurred51; areas involved in pain facilitation (posterior and middle cingulate subregions) were stimulated, whereas activity in a region usually associated with pain inhibition (supragenual anterior cingulate) was reduced. This study confirmed a strong association between visceral pain reporting and brain activation in predetermined brain regions involved in the affective and motivational aspects of the pain experience. The observed synergistic effect of IBS and abuse history on differential ACC activation suggests a mechanism to explain how afferent processing in the CNS can be associated with reporting of greater pain severity and poorer outcomes in this patient population. This and other research29,52–55 has suggested that dysregulation of central pain modulation is critical and may occur in various medical and psychological conditions. The challenge remains to alter this dysregulated afferent processing network reproducibly and to reverse the findings on functional brain imaging studies (by pharmacologic, psychological, or other therapeutic means), with a concomitant improvement in patient outcomes.

CLINICAL FEATURES

History

Typically, patients with FAPS are middle-aged and female. The history is one of chronic abdominal pain, often for more than 10 years, and the patient is often in distress at the time of initial consultation. The pain is frequently described as severe, constant, and diffuse. Pain is often a focal point in the patient’s life, may be described in emotional or bizarre terms (e.g., as nauseating or like a knife stabbing), and is not influenced by eating or defecation. The abdominal pain may be one of several painful symptoms or part of a continuum of painful experiences often beginning in childhood and recurring over time.22 FAPS sometimes coexists with other disorders, and the clinician must determine the degree to which one of these other conditions contributes to the FAPS. Frequently, FAPS will evolve in a patient who has had another well-defined gastrointestinal disorder, but who has been operated on one or more times and, following these operations, has developed chronic abdominal pain. Repetitive surgery in such patients is often performed for alleged intestinal obstruction caused by adhesions.

Patients with FAPS often have a psychiatric diagnosis of anxiety, depression, or somatization.24 They may minimize the role of psychological factors, possibly having learned in childhood that attention is more likely received when reporting illness but not emotional distress. A history of unresolved losses is a common feature.56 Symptoms frequently worsen soon after these events and recur on their anniversaries or during holiday seasons. A history of sexual and physical abuse is frequent and is predictive of poor health, refractoriness to medical care, and a high number of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and health care visits.43 Because patients do not usually volunteer an abuse history, physicians should inquire about this possibility, particularly in those with refractory symptoms.57

Finally, patients with FAPS may report poor social networks and exhibit ineffective coping strategies. They feel unable to decrease their symptoms and may “catastrophize”—that is, view their condition in pessimistic and morbid ways without any sense of control over the consequences. These cognitions are associated with greater pain scores that lead to a cycle of more illness reporting, more psychological distress, and poorer clinical outcomes.58 For many, the illness provides social support via increased attention from friends, family, and physicians.

Physical Examination

Certain physical findings help support a diagnosis of FAPS, yet none is perfectly sensitive or specific. Abdominal palpation should begin at an area remote from the perceived site of maximal intensity. The patient’s behavior during abdominal palpation should be noted, with an emphasis on whether a change is noted during distracting maneuvers. Patients with FAPS usually lack signs of autonomic arousal. The presence of multiple abdominal surgical scars without clearly understood indications may suggest chronic pain behaviors that have led to unnecessary procedures. The closed eyes sign may be noted59; when the abdomen is palpated, the patient with FAPS may wince, with her or his eyes closed, whereas those with acute pain caused by organic pathology tend to keep their eyes open in fearful anticipation of the examination. Often, the stethoscope sign (i.e., gentle, distracting compression on a painful site of the abdomen with the diaphragm of the stethoscope), elicits a diminished behavioral response in a patient with FAPS, thereby affording a more accurate appraisal of the complaint of pain.

DIAGNOSIS AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

After obtaining a complete history, performing a thorough physical examination, and paying appropriate attention to psychosocial factors in the patient’s life, the scenario will often point the physician toward a diagnosis of FAPS. A physical examination that does not suggest evidence of organic intra-abdominal pathology, as well as normal results of a battery of routine laboratory tests, lends support to the contention that the patient’s pain is not the result of an identifiable structural disease. Recognition of the diagnostic criteria for FAPS (see Table 11-2), and failure to find evidence of another cause of chronic abdominal pain (see Table 11–1), should lead the physician to a diagnosis of FAPS. If the features of FAPS are absent or atypical, or if concerning abnormalities are found on physical examination (e.g., abdominal mass, enlarged liver) or on screening laboratory studies (e.g., anemia, hypoalbuminemia), another diagnosis should be considered and pursued accordingly. Not uncommonly, nonspecific abnormalities are found (e.g., a liver cyst) and require determination of their relevance to the patient’s symptoms.

TREATMENT

Establishing a Successful Patient-Physician Relationship

Early in the development of the patient-physician relationship, it is important to determine whether there are abnormal illness behaviors and associated psychiatric diagnoses, which are often present in patients with FAPS. The role of the family in relation to the patient’s illness should also be understood. Normally, family experiences with illness lead to emotional support and a focus on recovery. With dysfunctional family interactions, stresses are not managed in an optimal fashion, and diverting attention toward illness serves to reduce family distress.60 Dysfunction is seen when family members indulge the patient, assume undue responsibility in the patient’s management, or become the spokesperson for the patient. If such family dysfunction is observed, counseling may help the family develop more useful coping strategies. Cultural belief systems must also be understood, because patients may not comply with treatments that are inconsistent with their cultural values. It is important to gain knowledge of the patient’s psychosocial resources (i.e., the availability of social networks) that may assist in buffering the adverse effects of stress and improve the outcome.

It is essential for the physician to convey validation of illness to the patient by acknowledging the patient’s illness and the effect it has had on his or her life in a nonjudgmental fashion. This step is important in ensuring that the patient understands that the physician considers FAPS to be a medical illness. Empathy is primary, because it acknowledges the reality and distress associated with the patient’s pain. Providing an empathetic approach can provide benefit by improving adherence to a treatment plan, patient satisfaction, and clinical outcomes.61 It does not, however, equate with overreacting to the patient’s wish for a rapid diagnosis and overmedication or performing unnecessary diagnostic studies. Education is provided by eliciting the patient’s knowledge of the syndrome, addressing any concerns, explaining the nature of the symptoms, and ensuring understanding in all matters that have been discussed. It is helpful to reiterate that FAPS is a medical disorder and that symptoms can be attenuated by pharmacologic or psychological treatments that modify the regulation of pain control. Reassurance should be provided, because patients may fear serious disease. After the evaluation is complete, the physician should respond to the patient’s concerns in a clear, objective, and nondismissive manner. Both patient and physician must then negotiate the treatment. This approach will enable the patient to contribute to and take some responsibility for the treatment plan. Within the context of the patient’s prior experience, interests, and understanding, the physician should provide choices rather than directives. Adherence to a treatment plan is more likely when the patient has confidence that it will benefit him or her and its rationale is understood. Finally, the physician must set reasonable limits in relation to time and effort expended. The key to success is to maintain a trusting relationship, while setting proper boundaries.

Pharmacotherapy

There is a paucity of evidence from prospective, randomized, controlled trials to support the use of drug therapy in FAPS. Drug development in the area of functional gastrointestinal disorders, particularly FAPS, has been slow. A major reason for this slow progress is the rather empirical process for experimental testing that necessarily occurs in a symptom-based syndrome.62 Pharmacologic brain imaging approaches hold promise as a means to accelerate drug discovery and subsequent development.63 Despite these limitations, some specific medications have been used in the treatment of FAPS (see later). Peripherally acting analgesics (e.g., acetaminophen, aspirin, other NSAIDs) offer little benefit to patients with FAPS, given the pathophysiology of the disorder (i.e., a biopsychosocial disorder related to dysfunction of the brain-gut neuraxis). Moreover, narcotics and benzodiazepines should not be prescribed for treatment of FAPS, because of the potential for increased pain sensitivity and a lowering of the pain threshold, respectively. Furthermore, the omnipresent potential for drug dependency with these types of medications must be borne in mind. Importantly, prescribing such medications subordinates the development of more comprehensive treatment strategies to that of providing medication, can be counterproductive by leading to narcotic-induced potentiation of visceral pain, and can thus result in the narcotic bowel syndrome.63 Narcotic bowel syndrome may occur in patients with other gastrointestinal disorders or in patients with no other structural intestinal disease who have been exposed to high doses of narcotic medication. The clinical scenario is dominated by chronic abdominal pain that continues to worsen, despite the use of escalating doses of narcotics. The keys to successful management of this disorder include the timely recognition of the syndrome followed by the establishment of an effective physician-patient relationship and graded tapering of the narcotic, with simultaneous institution of medical therapy to mitigate the effects of opiate withdrawal.63

As in the treatment of other chronic pain disorders, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) can be helpful in FAPS.64–66 The benefit of these medications is derived from their ability to improve pain directly and treat associated depression. In general, TCAs have been shown to be effective but can cause anticholinergic effects, hypotension, sedation, and cardiac arrhythmias. They can be given in dosages lower than those used to treat major depression (e.g., desipramine, 25 to 100 mg/day at bedtime) to reduce side effects. However, dosage increases may be needed, particularly if the patient has psychiatric comorbidity. There is less evidence for the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in FAPS. These medications may cause agitation, sleep disturbance, vivid dreams, and diarrhea but are much safer than TCAs if taken in an overdose. In most cases, administration of a single daily dose (e.g., 20 mg of fluoxetine, paroxetine, or citalopram) will suffice. Although the efficacy of SSRIs for pain control is not well established, this class of drugs has additional benefits because they are anxiolytic and helpful for patients with social phobia, post-traumatic stress disorder, panic disorder, and obsessional thoughts related to their condition. Drug combinations (e.g., TCAs with SSRIs) have little support for their use in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders.67

Anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine and gabapentin have been evaluated in other chronic pain syndromes but have no proven efficacy in FAPS. These drugs may find a role as adjunctive agents in the future. As is the case for other peripherally acting analgesics, topical capsaicin would not be expected to be helpful in the management of FAPS.68 Leuprolide acetate may be of benefit for premenstrual females with FAPS,69 but the consequent reproductive hormonal effects of this therapy have dampened enthusiasm for this approach.

Mental Health Referral and Psychological Treatments

The mental health consultant may recommend any of several types of psychological treatments for pain management.21,70 Cognitive-behavioral treatment, which identifies maladaptive thoughts, perceptions, and behaviors, may be beneficial.65 Evidence from functional brain imaging suggests that this psychological intervention decreases activation from rectal stimulation in the central emotional regions that are typically hyperactive in chronic pain, such as the amygdala, ACC, and frontal cortex.71 Hypnotherapy has been investigated primarily in IBS, where the focus is on relaxation of the gut. A randomized, controlled trial in children that included 31 patients with FAPS has concluded that hypnotherapy is superior to standard medical therapy in reducing pain at one year of follow-up.72 Dynamic or interpersonal psychotherapy and relaxation training have less evidence to support their use in FAPS.

ROLE OF LAPAROSCOPY WITH LYSIS OF ADHESIONS

The value of laparoscopy with lysis of adhesions (adhesiolysis) in patients with chronic abdominal pain continues to be debated. Relevant studies generally have often been retrospective and nonrandomized, with varying criteria for selecting patients and durations of follow-up. Therefore, the role of adhesiolysis is difficult to assess. Prospective observational investigations have shown improvement in 45% to 90% of patients.73–76 Perhaps most provocative is a prospective, blinded, randomized investigation performed by Swank and colleagues in which patients who were found at laparoscopy to have adhesions were randomized to undergo adhesiolysis or no treatment.77 At 12 months of follow-up, patients in both groups reported substantial pain relief and improved quality of life; however, there were no differences between the groups. The authors concluded that laparoscopic adhesiolysis could not be recommended in this setting. Given these somewhat conflicting data, it seems reasonable to withhold laparoscopy in most patients with chronic abdominal pain, with the understanding that, on occasion, the procedure may be of some benefit. The challenge for the future will be to define which patients will benefit from such intervention.

Bixquert-Jiménez M, Bixquert-Pla L. Antidepressant therapy in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;28:485-92. (Ref 66.)

Clouse RE, Mayer EA, Aziz Q, et al. Functional abdominal pain syndrome. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al, editors. Rome III. The functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, Va: Degnon Associates; 2006:557. (Ref 21.)

Drossman DA, Ringel Y, Vogt B, et al. Alterations in brain activity associated with resolution of emotional distress and pain in a case of severe IBS. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:754-61. (Ref 50.)

Drossman DA. Brain imaging and its implications for studying centrally targeted treatments in irritable bowel syndrome: A primer for gastroenterologists. Gut. 2005;54:569-73. (Ref 29.)

Drossman DA. Functional abdominal pain syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:353-65. (Ref 24.)

Kuan LC, Li YT, Chen FM, et al. Efficacy of treating abdominal wall pain by local injection. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;45:239-43. (Ref 10.)

Lackner JM, Lou Coad M, Mertz HR, et al. Cognitive therapy for irritable bowel syndrome is associated with reduced limbic activity, GI symptoms, and anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:621-38. (Ref 71.)

Mayer EA, Naliboff BD, Craig AD. Neuroimaging of the brain-gut axis: From basic understanding to treatment of functional GI disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1925-42. (Ref 54.)

Peterson LL, Cavanaugh DL. Two years of debilitating pain in a football spearing victim: Slipping rib syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1634-7. (Ref 17.)

Ringel Y, Drossman DA, Leserman JL, et al. Effect of abuse history on pain reports and brain responses to aversive visceral stimulation: An FMRI study. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:396-404. (Ref 51.)

Ringel Y. New directions in brain imaging research in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Dig Dis. 2006;24:278-85. (Ref 52.)

Sperber AD, Morris CB, Greemberg L, et al. Development of abdominal pain and IBS following gynecological surgery: A prospective, controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:75-84. (Ref 30.)

Swank DJ, Swank-Bordewijk SCG, Hop WCJ, et al. Laparoscopic adhesiolysis in patients with chronic abdominal pain: A blinded randomized controlled multi-centre trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1247-51. (Ref 77.)

Vlieger AM, Menko-Frankenhuis C, Wolfkamp SCS, et al. Hypnotherapy for children with functional abdominal pain or irritable bowel syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1430-6. (Ref 72.)

1. Ray BS, Neill CL. Abdominal visceral sensation in man. Ann Surg. 1947;126:709-23.

2. Ryle JA. Visceral pain and referred pain. Lancet. 1926;1:895.

3. Applegate WV. Abdominal cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome. Surgery. 1972;71:118-24.

4. Lindsetmo RO, Stulberg J. Chronic abdominal wall pain—A diagnostic challenge for the surgeon. Am J Surg. 2009;198:129-34.

5. Hershfield NB. The abdominal wall. A frequently overlooked source of abdominal pain. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;14:199-202.

6. Carnett JB. Intercostal neuralgia as a cause of abdominal pain and tenderness. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1926;42:625-32.

7. Borg-Stein J, Simons DG. Myofascial pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:S40-7.

8. Sharp HT. Myofascial pain syndrome of the abdominal wall for the busy clinician. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;46:783-8.

9. Greenbaum DS, Greenbaum RS, Joseph JG, et al. Chronic abdominal wall pain. Diagnostic validity and costs. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:1935-41.

10. Kuan LC, Li YT, Chen FM, et al. Efficacy of treating abdominal wall pain by local injection. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;45:239-43.

11. Nazareno J, Ponich T, Gregor J. Long-term follow-up of trigger point injections for abdominal wall pain. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19:561-5.

12. Costanza CD, Longstreth GF, Liu AL. Chronic abdominal wall pain: Clinical features, health care costs and long-term outcome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:395-9.

13. Paajanen H. Does laparoscopy used in open exploration alleviate pain associated with chronic intractable abdominal wall neuralgia? Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1835-8.

14. Cyriax EF. On various conditions that may simulate the referred pains of visceral disease and a consideration of these from the point of view of cause and effect. Practitioner. 1919;102:314-22.

15. Davies-Colley R. Slipping rib. BMJ. 1922;1:432.

16. Heinz GJIII, Zavala DC. Slipping rib syndrome: Diagnosis using hooking maneuver. JAMA. 1977;237:794-5.

17. Peterson LL, Cavanaugh DL. Two years of debilitating pain in a football spearing victim: Slipping rib syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1634-7.

18. Whitcomb DC, Martin SP, Schoen RE, et al. Chronic abdominal pain caused by thoracic disc herniation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:835-7.

19. Longstreth GF. Diabetic thoracic polyradiculopathy: Ten patients with abdominal pain. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:502-5.

20. Drossman DA. The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al, editors. Rome III. The functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, Va: Degnon Associates; 2006:1.

21. Clouse RE, Mayer EA, Aziz Q, et al. Functional abdominal pain syndrome. editors., (eds) Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al, editors. Rome III. The functional gastrointestinal disorders, 3rd ed. 2006, Degnon:McLean, Va, 557

22. Drossman DA. Patients with psychogenic abdominal pain: Six years’ observation in the medical setting. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1549-57.

23. Sloth H, Jorgensen LS. Chronic nonorganic upper abdominal pain: Diagnostic safety and prognosis of gastrointestinal and nonintestinal symptoms—a 5- to 7-year follow-up study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1988;23:1275-80.

24. Drossman DA. Functional abdominal pain syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:353-65.

25. Drossman DA. Presidential Address: Gastrointestinal illness and biopsychosocial model. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:258-67.

26. Townsend CO, Sletten CD, Bruce BK, et al. Physical and emotional functioning of adult patients with chronic abdominal pain: Comparison with patients with chronic back pain. J Pain. 2005;6:75-83.

27. Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, et al. U.S. Householder Survey of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569-80.

28. Barbara G, Wang B, Stanghellini V, et al. Mast cell-dependent excitation of visceral-nociceptive sensory neurons in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:26-37.

29. Drossman DA. Brain imaging and its implications for studying centrally targeted treatments in irritable bowel syndrome: A primer for gastroenterologists. Gut. 2005;54:569-73.

30. Sperber AD, Morris CB, Greemberg L, et al. Development of abdominal pain and IBS following gynecological surgery: A prospective, controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:75-84.

31. Wood JD, Grundy D, Al-Chaer ED, et al. Fundamentals of neurogastroenterology: Basic science. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al, editors. Rome III. The functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, Va: Degnon Associates; 2006:31.

32. Wall PD, Melzack R, editors. Textbook of pain, 4th ed, Edinburgh: Churchill-Livingstone, 1999.

33. Rainville P, Duncan GH, Price DD, et al. Pain affect encoded in human anterior cingulate but not somatosensory cortex. Science. 1997;277:968-71.

34. Oudenhove LV, Demttenaere K, Tack J, et al. Central nervous system involvement in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:663-80.

35. Fields HL, Basbaum AI. Central nervous system mechanisms of pain modulation. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al, editors. Rome III. The functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, Va: Degnon Associates; 2006:243.

36. Wilder-Smith CH, Schindler D, Lovblad K, et al. Brain functional magnetic resonance imaging of rectal pain and activation of endogenous inhibitory mechanisms in irritable bowel syndrome patient subgroups and healthy controls. Gut. 2004;53:1595-601.

37. Munakata J, Naliboff B, Harraf F, et al. Repetitive sigmoid stimulation induces rectal hyperalgesia in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:55-63.

38. Buéno L, Fioramonti J, Garcia-Villar R. Pathobiology of visceral pain: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. III. Visceral afferent pathways: A source for new therapeutic targets for abdominal pain. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;278:G670-6.

39. Whitehead WE, Engel BT, Schuster MM. Irritable bowel syndrome: Physiological and psychological differences between diarrhea-predominant and constipation-predominant patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1980;25:404-13.

40. Nozu T, Kudaira M, Kitamori S, et al. Repetitive rectal painful distention induces rectal hypersensitivity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:217-22.

41. DePonti F. Pharmacology of serotonin: What a clinician should know. Gut. 2004;53:1520-35.

42. Drossman DA, Whitehead WE, Toner BB, et al. What determines severity among patients with painful functional bowel disorders? Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:974-80.

43. Drossman DA, Li Z, Leserman J, et al. Health status by gastrointestinal diagnosis and abuse history. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:999-1007.

44. Ringel Y, Drossman DA. From gut to brain and back—a new perspective into functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Psychom Res. 1999;47:205-10.

45. Gwee KA, Leong YL, Graham C, et al. The role of psychological and biological factors in postinfective gut dysfunction. Gut. 1999;44:400-6.

46. Mertz H, Morgan V, Tanner G, et al. Regional cerebral activation in irritable bowel syndrome and control subjects with painful and non-painful rectal distention. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:842-8.

47. Silverman DHS, Ennes H, Munakata JA, et al. Differences in thalamic activity associated with anticipation of rectal pain between IBS patients and normal subjects. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:A1006.

48. Mayberg HS, Liotti M, Brannan SK, et al. Reciprocal limbic-cortical function and negative mood: Converging PET findings in depression and normal sadness. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:675-82.

49. Mayberg HS, Brannan SK, Mahurin RK, et al. Cingulate function in depression: A potential predictor of treatment response. Neuroreport. 1997;8:1057-61.

50. Drossman DA, Ringel Y, Vogt B, et al. Alterations in brain activity associated with resolution of emotional distress and pain in a case of severe IBS. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:754-61.

51. Ringel Y, Drossman DA, Leserman JL, et al. Effect of abuse history on pain reports and brain responses to aversive visceral stimulation: An FMRI study. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:396-404.

52. Ringel Y. New directions in brain imaging research in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Dig Dis. 2006;24:278-85.

53. Chang L. Brain responses to visceral and somatic stimuli in irritable bowel syndrome: A central nervous system disorder? Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:271-9.

54. Mayer EA, Naliboff BD, Craig AD. Neuroimaging of the brain-gut axis: From basic understanding to treatment of functional GI disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1925-42.

55. Bremner JD. The relationship between cognitive and brain changes in posttraumatic stress disorder. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1071:80-6.

56. Hislop IG. Childhood deprivation: An antecedent of the irritable bowel syndrome. Med J Aust. 1979;1:372-4.

57. Drossman DA, Leserman J, Nachman G, et al. Sexual and physical abuse in women with functional or organic gastrointestinal disorders. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:828-33.

58. Drossman DA, Li Z, Leserman J, et al. Effects of coping on health outcome among female patients with gastrointestinal disorders. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:309-17.

59. Gray DWR, Dixon JM, Collin J. The closed-eyes sign: An aid to diagnosing nonspecific abdominal pain. BMJ. 1988;297:837.

60. Whitehead WE, Crowell MD, Heller BR, et al. Modeling and reinforcement of the sick role during childhood predicts adult illness behavior. Psychosom Med. 1994;6:541-50.

61. Stewart M, Brown JB, Boon H, et al. Evidence on patient-doctor communication. Cancer Prev Control. 1999;3:25-30.

62. Mayer EA, Bradesi S, Chang L, et al. Functional GI disorders: From animal models to drug development. Gut. 2008;57:384-404.

63. Grunkemeier DMS, Cassara JE, Dalton CB, Drossman DA. The narcotic bowel syndrome: Clinical features, pathophysiology, and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1126-39.

64. Jackson JL, O’Malley PG, Tomkins G, et al. Treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders with antidepressants: A meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2000;108:65-72.

65. Drossman DA, Toner BB, Whitehead WA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus education and desipramine versus placebo for moderate to severe functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:19-31.

66. Bixquert-Jiménez M, Bixquert-Pla L. Antidepressant therapy in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;28:485-92.

67. Nair D, Prakash C, Lustman PJ, et al. Added value of tricyclic antidepressants for functional gastrointestinal symptoms in patients on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(Suppl):S316.

68. Mason L, Moore RA, Derry S, et al. Systematic review of topical capsaicin for the treatment of chronic pain. BMJ. 2004;328:991.

69. Mathias JR, Clench MH, Abell TL, et al. Effect of leuprolide acetate in treatment of abdominal pain and nausea in premenopausal women with functional bowel disease: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1347-55.

70. Lackner JM, Mesmer C, Morley S, et al. Psychological treatments for irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Consulting Clin Psychol. 2004;72:1100-13.

71. Lackner JM, Lou Coad M, Mertz HR, et al. Cognitive therapy for irritable bowel syndrome is associated with reduced limbic activity, GI symptoms, and anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:621-38.

72. Vlieger AM, Menko-Frankenhuis C, Wolfkamp SCS, et al. Hypnotherapy for children with functional abdominal pain or irritable bowel syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1430-6.

73. Dunker MS, Bemelman WA, Vijn A, et al. Long-term outcomes and quality of life after laparoscopic adhesiolysis for chronic abdominal pain. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2004;11:36-41.

74. Swank DJ, van Erp WFM, Repelaer van Driel OJ, et al. A prospective analysis of predictive factors on the results of laparoscopic adhesiolysis in patients with chronic abdominal pain. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13:88-94.

75. Onders RP, Mittendorf EA. Utility of laparoscopy in chronic abdominal pain. Surgery. 2003;134:549-54.

76. Paajanen H, Julkunen K, Waris H. Laparoscopy in chronic abdominal pain. A prospective nonrandomized long-term follow-up study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:110-14.

77. Swank DJ, Swank-Bordewijk SCG, Hop WCJ, et al. Laparoscopic adhesiolysis in patients with chronic abdominal pain: A blinded randomized controlled multi-centre trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1247-51.