8 Choosing the Biopsy Type

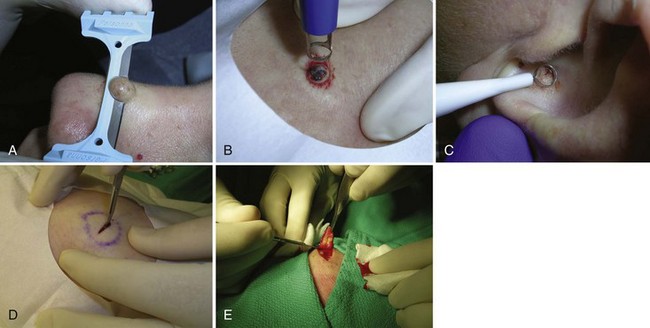

A biopsy of the skin is performed to ascertain or confirm the diagnosis of skin lesions, both benign and malignant, and in many cases, to simultaneously remove them. Skin biopsies can be categorized into five types (Figure 8-1):

FIGURE 8-1 Five biopsy methods: (A) Shave; (B) punch; (C) curettement; (D) incision; (E) excision.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

Choosing which type of biopsy to perform influences the diagnostic yield, the cosmetic result, and the cost and time required for the physician to perform the procedure. The clinician must also understand the parameters for selecting that portion of a lesion that will provide the most information to a pathologist.1–3

General Principles

Shave Biopsy

The choice of biopsy technique has much to do with the physician’s initial assessment of the lesion. It is particularly important to consider the depth of involvement within the skin. The shave method is particularly suited to lesions confined to the epidermis and upper dermis, such as seborrheic or actinic keratoses, basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), and many benign nevi. Chapter 9, The Shave Biopsy, provides detailed information on this topic.

Punch Biopsy

A punch biopsy is the method of choice for most inflammatory or infiltrative diseases and for other lesions in which the predominant pathology lies in the dermis, such as a dermatofibroma. A punch biopsy produces a full-thickness specimen of the skin that, when done properly, extends to the subcutaneous fat. Chapter 10, The Punch Biopsy, provides detailed information on this topic.

Curettement Biopsy

Using a sharp curette is another method of biopsy. A disposable 3-mm curette is a good choice. This size of curette is best suited for difficult areas such as in the canthal folds where the skin is thin and mobile or in areas that are difficult to access such as an ear canal or nostril. Care must be taken not to go too deep and injure vital tissue. A small lesion can be curetted off and sent to pathology (Figure 8-2).

Incisional and Excisional Biopsy

The term incisional biopsy refers to the process of excising a portion of a lesion using full-thickness excision techniques. It is used for obtaining a large sample of a large lesion, but not the entire lesion. The term excisional biopsy refers to full-thickness excision of the entire lesion. Both generally require some type of closure, which is usually done with sutures. See Chapter 11 for more detailed information about elliptical excisions.

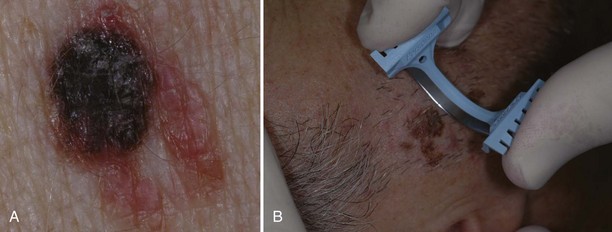

Excision may be the biopsy method of choice for large potentially malignant lesions since a more focal biopsy may miss the malignant portion of the abnormality. Lesions highly suggestive of malignant melanoma (Figure 8-3) are often excised since the resulting specimen will provide a full-depth sample, which is needed for prognosis and treatment. The disadvantages of excising all “suspicious” lesions are that (1) it can lead to overtreatment for benign lesions and more tissue is removed than what is needed, which adds to the cost and increases scarring and other complications (e.g., excising a totally benign nevus or minimally atypical one), and (2) another surgery is often required because the initial ellipse is often performed with margins smaller than recommended for definitive treatment.

The excisional technique is also used to diagnose and remove dermal lesions, subcutaneous cysts and tumors (epidermal cysts and lipomas), and lesions that are too deep or too large to be removed by punch (generally greater than 5 mm in diameter) or shave. Cysts and especially lipomas may be removed with a deep linear incision rather than removing an elliptical portion of the skin (see Chapter 12, Cysts and Lipomas).

Choice of Site to Biopsy

If a “rash” or inflammatory process is present, select a “fresh” lesion that has recently appeared rather than one that has been present longer. Oftentimes, older lesions have been excoriated or secondarily infected, obscuring the primary pathology. Choose a lesion on the upper body rather than the lower body whenever possible (Figure 8-4). The histology may be easier to interpret and the healing should be more rapid. Biopsies of the lower legs are more likely to get infected or have delayed healing. Also avoid the axilla and groin if possible because these areas are more prone to infections.

If a vesicular-bullous reaction is present, it is best to biopsy an intact bulla with some normal tissue (Figure 8-5). It is helpful for the pathologist to examine the edge of the bulla to characterize the exact etiology of the disease process.

FIGURE 8-5 A shave biopsy of an intact blister in a patient with suspected bullous pemphigoid.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

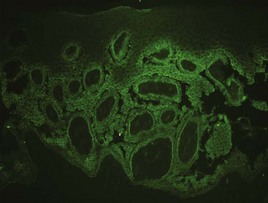

When direct immunofluorescence (DIF) testing is to be done, biopsies are usually taken from perilesional skin (Figure 8-6). That means the biopsy will not include the bulla or erosion at all. The specimen is generally obtained with a shave or punch biopsy next to the visible pathology. DIF studies are especially helpful for autoimmune bullous diseases because antibodies will light up in the skin (Figure 8-7). They do not have to be done on the initial biopsy but may be performed to clarify and add data to a standard biopsy for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. There are only a few autoimmune diseases in which lesional skin is preferred (see Table 8-1). A 4-mm punch is adequate. It must be sent to the lab in special Michel’s media (or on saline-soaked gauze). This media should be kept in the refrigerator and can expire. If the cap is on tight and the media has just expired, it is probably still usable. See Table 8-1 for more information on the DIF biopsy.

|

Disease |

Location of Biopsy |

Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Pemphigus vulgaris | Perilesional | Intercellular deposition of IgG. |

| Pemphigus foliaceus | Perilesional | Intercellular deposition of IgG. |

| IgA pemphigus | Perilesional | Intercellular deposition of IgA. |

| Paraneoplastic pemphigus | Perilesional | Intercellular deposition of IgG. Antibodies also directed to simple or transitional epithelium (rat bladder). |

| Bullous pemphigoid | Perilesional | Linear basement membrane staining with IgG and/or C3. Salt split samples will localize to the epidermal side. |

| Cicatricial pemphigoid (MMP) | Perilesional skin, mucosa, or conjunctiva | Linear basement membrane staining with IgG and/or C3. Salt split samples show variable localization. |

| Herpes gestationis | Perilesional | Linear basement membrane staining with C3, IgG is generally less pronounced. |

| Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita | Perilesional | Heavy IgG and/or C3 along the basement membrane zone. Salt split samples will localize to the dermal side. |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis | Lesional or normal skin from disease-prone area | Granular IgA within dermal papillae. |

| Lichen planus | Inflamed, but nonulcerated mucosa or skin | Clumps of cytoid bodies and fibrinogen in the basement membrane zone. |

| Lupus band test | Normal skin | Granular IgG or IgM along the basement membrane zone. |

| Discoid lupus erythematosus | Lesional skin | Granular deposition of IgG, IgM, and/or IgA along the basement membrane zone in conjunction with cytoid bodies. |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Lesional skin | Same as for discoid lupus. |

| Bullous lupus erythematosus | Perilesional skin | Heavy IgG and/or C3 along the basement membrane zone. |

| Vasculitis | Early lesion | Perivascular IgA: Henoch Schoenlein purpura. Perivascular IgM/IgG/C3: other forms of vasculitis. |

| Linear IgA dermatitis | Perilesional skin | Linear IgA deposition at the basement membrane zone. |

| Porphyria/pseudoporphyria cutanea tarda | Perilesional | Linear IgG, IgM, and C3 around vessels and dermal-epidermal junction. |

Source: Courtesy of Robert Law, MD.

If a basal cell carcinoma is suspected, it is often easy to shave off the whole lesion. If the lesion is large, almost any area can be biopsied but it is better to select a raised-up border rather than an ulcerated portion. Biopsying the latter may inaccurately provide a pathology specimen that shows only inflammation and reparative debris if not sampled deeply enough. Curettement and punch methods can also be used. An advantage with curettement is that if the tissue is necrotic, it feels “soft” with curetting and also has a classic appearance. The appearance and feel can confirm the initial impression, and treatment can be performed immediately (electrodesiccation and curettage ×3) (see Chapter 14, Electrosurgery).

If a melanoma is suspected, it is best to provide a specimen with adequate depth. Unfortunately choosing the darkest and most raised area does not guarantee the correct diagnosis. Although a full elliptical excision has been considered the gold standard, in some circumstances this is not desirable, for instance, in a large pigmented lesion on the face. In cases of suspected lentigo maligna melanoma on the face, a broad shave provides a better sample than a few punch biopsies and is less deforming that a large full-thickness biopsy. It is also just not practical to perform an elliptical excision on every potentially malignant pigmented lesion. It may be better in some instances to sample the whole lesion with a broad deep shave than to do one or more punch biopsies. Of course, sooner or later, an unsuspecting melanoma may be biopsied with a shave that misses the true depth of the lesion. Note, however, that it is far better to biopsy a lesion—regardless of the method—and find a melanoma early than to delay and procrastinate, thus missing an opportunity for early detection and treatment.4 Suspected early thin melanomas can easily be biopsied with a deep shave technique. When sampling a suspected thick nodular melanoma, a deep sample will be needed to find the Breslow level and plan the definitive surgery. Dermoscopy (see Chapter 32) is a tool that can help you choose the most suspicious area to biopsy in a large lesion if it is impractical to biopsy the whole lesion. Fortunately, nonexcisional biopsies do not negatively influence melanoma patient survival and, in general, do closely correlate with the true depth of the lesion.5,6

Is it cancer?

Pigmented Lesions: Melanoma and Its Differential Diagnoses

Early detection and prompt removal of melanoma can be lifesaving. The early signs of melanoma are summarized as ABCDE, where A = asymmetry, B = borders (irregular), C = color (variegated), D = diameter (greater than 6 mm), and E = evolving and elevation (Figure 8-8).7 Some have suggested adding an F for a change in feeling since some melanomas present with onset of pruritus in a nevus. However, not all melanomas show these signs and not all lesions with these signs are melanomas. The dermatoscope can be used to increase your sensitivity and specificity for detecting melanoma (see Chapter 32, Dermoscopy). Whether or not a dermatoscope is used, it is incumbent on the clinician to biopsy any suspicious pigmented lesion. We cannot overemphasize that patient history is of utmost importance in the evaluation of any lesion and should never be taken lightly. If a patient is concerned that a pigmented lesion has changed, most often it deserves a biopsy/removal.

Pigmented lesions highly suggestive of melanoma should be biopsied for depth because treatment is primarily based on that parameter. Other considerations needed to select the proper treatment include whether there is neural or vascular involvement and whether ulceration is present. Some suggest that all suspected melanomas be biopsied using the excisional technique (full-thickness excision with suture closure). This practice presents several problems: (1) How much free margin should be obtained? Most commonly, a simple excision with a margin of 5 mm (melanoma in situ) to 1 cm (up to 1 mm of invasion with no other warning signs on pathology) is needed for treatment. If the invasion is greater than 1.5 mm, a 2-cm margin is recommended.8,9 So, should the excisional biopsy always have a 1-cm margin? Most lesions will not be a melanoma. Should the excision then just remove the lesion with no free margins? Using excision as the primary approach for biopsying a suspicious lesion will not only cost more and, in many cases, remove an excess amount of normal tissue, but will most likely require that the patient have a second surgery if a melanoma is found. (2) Full surgical excision takes significant time and skills. Many primary care clinicians are not prepared to excise all suspicious lesions. Referral for a biopsy takes time, increases the cost, and may not be readily available. Patients also may not comply with seeing another physician. The optimal time to biopsy is when the lesion is first evaluated. A shave or a punch biopsy takes only a few minutes and then therapy can be based on the results. This approach saves time and limits costs, while reducing unnecessary scarring, infected wounds, and return visits to the office. Survival time does not appear to be influenced by the method of biopsy.5

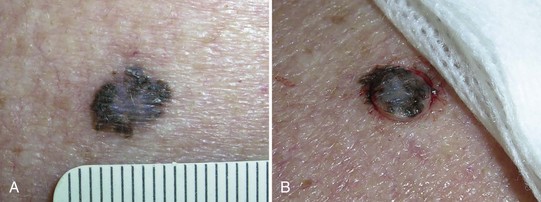

If a melanoma is truly suspected, a deep shave biopsy may indeed be the ideal method of sampling (Figure 8-8B). A punch biopsy can have significant sampling errors and false-negative results unless the whole lesion is removed or multiple biopsies are obtained from larger lesions. The object is to detect melanoma early and save lives. If a larger lesion is atypical in appearance, the entire lesion will need to be removed but the initial biopsy will at least help determine required margins for excision, or if a referral is indicated. A punch biopsy may be used as long as a negative (nonmalignant) biopsy of a suspicious lesion larger than the initial punch is followed up with an excision in which all the remaining tissue is excised and examined (Figure 8-9).

Pigmented lesions that are unusual and are considered to have a low, but definite, possibility of malignancy or dysplasia (atypia) also require prompt biopsy. If these lesions are small (up to 6 to 7 mm), a saucer-type shave excision with narrow margins (1 to 2 mm) is the method of choice. Very small lesions, those less than 3 mm in diameter, can often be adequately excised by using the deep shave technique or a 4-mm punch to remove the entire lesion. Large lesions (those greater than 2 cm in diameter), with a low level of suspicion, may be investigated by doing a 4-mm punch biopsy in the area of highest suspicion (i.e., the blackest area or the area of greatest elevation) or with frank excision (Figure 8-10).

Lentigo Maligna

Lentigo maligna (LM) is one type of melanoma in situ. Flat, macular lesions suspected of being lentigo maligna (Figure 8-11) present a problem because many of these lesions are very large (often over 2 cm in diameter) and frequently are present on the face in 50 to 70 year olds. They are interesting because the radial growth phase may last for years and the vertical (invasive) phase may never develop. Excisional biopsy is preferred for small lesions, but this method may be impractical for large lesions. A broad shave biopsy of suspected LM or lentigo maligna melanoma (LMM) should provide a better tissue sample than one or more punch biopsies and will not cause the cosmetic deformities of a large full-thickness biopsy (Figure 8-11).

Atypical Moles (Dysplastic Nevi)

Terminology can be confusing. Atypical and dysplastic are often used interchangeably in dermatologic communication. The current recommended NIH nomenclature, however, is “nevus with architectural disorder” (Figure 8-12). See Box 8-1 for further clarification.

FIGURE 8-12 Compound dysplastic melanocytic nevus (nevus with architecture disorder).

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

Box 8-1

Nevus with Architectural Disorder (Dysplastic Nevus)

Source: Courtesy of Terry L. Barrett, MD.

Although benign, atypical nevi have clinical, histologic, and biologic behavior distinct from common nevocellular nevi. Two percent to 8% of the population have nevi that fit the definition of atypical moles. Clinically, these nevi are large (5 to 12 mm in diameter), are characteristically multicolored (with shades of brown, tan, or pink), and have irregular borders that tend to be indistinct (Figure 8-12). They usually have a flat macular component, are frequently multiple, and are most common on the trunk. In contrast to common nevi, atypical moles usually begin to appear during adolescence and continue to appear during young adult life.

Patients with a few atypical moles can also be divided into those with a personal history or a first-degree relative with a history of melanoma, and those without such a history (sporadic atypical moles). Patients with sporadic atypical moles are probably not at as great a risk for developing melanoma.10,11

Benign Nevi

Many will request mole removal purely for cosmetic reasons. Alternatively, the lesions may be in areas of repeated trauma (e.g., from shaving, combing, irritation from clothes or jewelry). Shave biopsy is the treatment of choice for most totally benign-appearing nevi, and the lesion should still be sent for histological examination. In Figure 8-13, the raised lesion could be a benign nevus or a BCC. If the history suggests a nevus, a shave biopsy would be the method of choice. Removal of some nevi on the face may yield a better cosmetic result when accomplished by punch or meticulous excision when large. Size, location, age of the patient, history, and type of skin all are factored into the decision. Nevi with a deeper intradermal component tend to recur or become pigmented after shave removal especially in younger patients. A shave can still be performed but the patient should be forewarned as a part of informed consent that regrowth or pigment changes may still require full-depth excision later. For nevi with hair a shave biopsy is often too superficial to remove the deeper root of the hair follicle. In this instance, to reduce potential scarring from an excision, a shave can be performed and if hair does regrow, simple epilation techniques can remove it. It is again important to inform the patient of the potential for hair growth.

Seborrheic Keratoses

Most seborrheic keratoses will not need a biopsy. However, because some of these lesions mimic malignant tumors such as melanomas when they are darkly pigmented, biopsy should be performed if any doubt exists (Figure 8-10). Dermoscopy (see Chapter 32) can help make this distinction and avoid a biopsy in many cases. When performing a biopsy on seborrheic keratoses, care should be taken to avoid unnecessarily deep or destructive techniques. Seborrheic keratoses are epidermal lesions. Shave biopsy is the biopsy technique of choice unless the suspicion of melanoma is high. Treatment with cryotherapy without biopsy is very acceptable for lesions in which the clinical diagnosis is certain. However, lesions that fail to resolve after 6 weeks should be evaluated and a biopsy considered.

Nonpigmented Lesions Suspicious for Cancer

Actinic Keratoses

Actinic keratoses can be very superficial or hypertrophic. They are considered a precancerous lesion and as such, should be treated or biopsied. Thinner obvious lesions can be treated with topical agents, cryotherapy, or electrodesiccation without biopsy initially. If lesions persist after treatment, or if there is concern about a cancer at the base, then a shave biopsy or curettement is indicated. With high-risk lesions such as those with a cutaneous horn, a deeper saucer-type shave is best to provide the pathologist with enough tissue to discern invasion (Figure 8-14).

Keratoacanthomas

The history and clinical appearance of keratoacanthomas (KAs) are quite distinct. They grow rapidly in a matter of months and appear most like a BCC with central keratin plug (Figure 8-15). It is considered a variant of SCC. If suspected, smaller lesions (8 to 10 mm) can be removed with a deep saucer-type shave followed by electrodesiccation and curettage (×3). For larger lesions, full-thickness excision is the best method of biopsy/removal.

Basal Cell Carcinoma

The majority of BCCs are relatively small (less than 1 cm), raised tumors on the face, head, neck, or exposed parts of the trunk and extremities. Nearly any method can be used to biopsy these lesions if their exact nature is uncertain. With curettement, the typical soft necrotic tissue can be identified so treatment with electrodesiccation and curettage (ED&C) can be immediately performed (see Chapter 14, Electrosurgery, and Chapter 34, Diagnosis and Treatment of Malignant and Premalignant Lesions). Shave biopsy can be used for most of these tumors and has the advantage of not producing a deeper or full-thickness wound should the lesion prove not to be a cancer (Figure 8-16). A punch biopsy of the raised “pearly border” can also be performed. Although data on this issue is not available, some clinicians will not use ED&C on a BCC that was diagnosed with a punch biopsy. If an excisional biopsy is planned because the diagnosis of BCC is likely, then 3 to 5 mm of clear margin should be included in the specimen to reduce the likelihood that further excisions will be needed (see Chapter 11, The Elliptical Excision).

FIGURE 8-16 A razor blade being used for a shave biopsy of a nodular BCC.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

Sclerosing (morpheaform, aggressive) BCCs are flat and more difficult to diagnose clinically and histopathologically. Therefore, a punch specimen is usually preferred, although a deeper shave often will be adequate to make the diagnosis. However, as seen in Figure 8-17, these lesions are most often flat and difficult to biopsy with the shave technique. It is difficult to discern margins of the abnormality clinically and for all but the smallest of lesions, excision will be needed for treatment. These lesions are fibrotic and often do not lend themselves to curettement. They also have a higher recurrence rate.

FIGURE 8-17 A morpheaform basal cell carcinoma on the face. The preferred biopsy type is a punch biopsy or a deep shave.

(Courtesy of the Skin Cancer Foundation, New York, NY.)

Pigmented BCCs can appear very much like melanomas (Figure 8-18). In these instances, a biopsy for depth may be indicated.

Squamous Cell Carcinomas

Squamous cell carcinoma can be difficult to diagnose by histopathology. It can easily be mistaken by the pathologist for actinic keratosis, especially if the biopsy was made along the periphery of the lesion. If an SCC is suspected, sample the central portion of the lesion using a deep shave or a punch biopsy. When performing a shave biopsy, care must be taken to get a specimen with adequate depth to enable the pathologist to render an accurate opinion (Figure 8-19). As with BCC, the physician should carefully record the site of biopsy. For large lesions, particularly those in or around the oral cavity and ears, it is important to check for lymphadenopathy. Prompt treatment after diagnosis of SCC is essential because some of these lesions have the potential for metastasis (see Chapter 34).

Inflammatory Disorders

Various inflammatory disorders present as unknown rashes, and a punch biopsy will provide adequate tissue for diagnosis (e.g., lichen planus, psoriasis and cutaneous lupus erythematosus). The typical malar rash of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in a patient with a strongly positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) does not require a biopsy for diagnosis. However, some cases of cutaneous lupus may need a biopsy for diagnosis (Figure 8-21). Lichen planus presents with different morphologies from atrophic to hypertrophic, from solid to bullous. A punch biopsy is needed for definitive diagnosis (Figure 8-22). A 4-mm punch biopsy is usually preferred (see Chapter 10, The Punch Biopsy).

Almost all inflammatory dermatoses have a dermal component. Punch biopsy is necessary to preserve the dermal architecture so the dermatopathologist can evaluate the cellular infiltrate, both as to its nature and its pattern. In most cases in which a punch biopsy is indicated, the biopsy need only go through the dermis, and the specimen is cut off at the top of the subcutaneous fat. However, to diagnose erythema nodosum (Figure 8-23), the punch specimen should include as much of the subcutaneous fat as possible. This is because erythema nodosum is really a panniculitis, with the overlying dermis secondarily involved.

Infiltrative Disorders

Infiltrative disorders, such as granulomas, also require a punch rather than a shave biopsy to deliver a suitable specimen for dermatopathologic examination. Examples of infiltrative disorders include sarcoidosis (Figure 8-24), cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (Figure 8-25), and granuloma annulare (Figure 8-26). Morphea (Figure 8-27) and lichen sclerosis (Figure 8-28) are diagnosed with punch biopsies as well.

FIGURE 8-27 Morphea (localized scleroderma) on the back of a man. A 4-mm punch biopsy was used to make the diagnosis.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

Erythroderma

Erythroderma is a dangerous dermatologic condition in which the skin becomes red and begins to peel off in flakes (Figure 8-29). The impaired skin barrier makes the person vulnerable to dehydration and infection. It is the dermatologic manifestation of a number of underlying disease processes, including various forms of dermatitis, drug reactions, and lymphoproliferative disorders. The key to proper diagnosis and treatment is contingent on a good biopsy.

FIGURE 8-29 Erythroderma in a 19-year-old woman. A stat punch biopsy was done to obtain a diagnosis.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

A short differential diagnosis of erythroderma includes:

Because erythroderma covers most of the body, there are many areas from which to choose for the biopsy. Like most diagnostic challenges, the 4-mm punch biopsy is the standard method for obtaining tissue. Choose an area on the upper body such as the arm or trunk with significant skin involvement. If there are pustules as in possible pustular psoriasis, biopsy a pustule (Figure 8-30). Send this for a stat pathology consult while initiating treatment. Many patients will need hospitalization, but it is usually easiest to do the biopsy in the office before transferring the patient to the hospital.

Bullous Lesions

Many bullous lesions are seen with bullous impetigo to pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid (Figure 8-31). Although bullous impetigo can be diagnosed and treated based on history and physical exam, the autoimmune forms of bullous diseases should be biopsied while initiating treatment. These diseases are often treated with prolonged courses of oral steroids and immunosuppressive medications, so it is essential to have the correct diagnosis from the start. Start with one 4-mm punch biopsy of an established lesion including the edge of the blister. A shave biopsy is an alternative as long as the epidermis of the blister stays attached to the specimen. If possible biopsy a new blister and remove the whole lesion. This is sent in formalin for H&E staining. Further information is obtained with a 4-mm punch biopsy for DIF. Biopsy the perilesional skin and send the specimen in Michel’s media (see earlier discussion under Choice of Site to Biopsy). If this media is not available, send the specimen in a sterile urine cup on top of a sterile gauze soaked with sterile saline and alert the pathologist that the specimen is not in Michel’s media. See Table 8-1 for more detailed information on where and how to biopsy tissue for DIF.

Considerations for Specific Anatomic Areas

Scalp (Alopecia)

Biopsy is almost always needed to diagnose the various forms of scarring alopecia (including lichen planopilaris and folliculitis decalvans) (Figure 8-32). Androgenic alopecia, telogen effluvium, and alopecia areata are not scarring and can often be diagnosed clinically without a biopsy. The type of inflammatory infiltrates seen on histology can vary and are used to classify the scarring alopecias:

Ears, Eyelids, Nose, and Lips

Shave biopsies are often preferred on the ears, eyelids, nose, and lips. If a punch biopsy is indicated, use of a 3-mm punch will avoid most problems with dog ears (see Chapter 10). On the ears it is best to avoid cutting into the cartilage unless it is necessary for the diagnosis. On the eyelids, care must be taken to avoid the conjunctival margin and the lacrimal ducts to avoid scarring that will lead to eye dysfunction. On the nose, a shave biopsy is often preferred if the lesion is not pigmented. A large punch biopsy can distort the anatomy of the nose. On the lips, care must be taken to align the vermilion border if any sutures are used.

How to Submit A Specimen to the Lab

To obtain the most accurate diagnosis from the pathologist, it is important to provide all of the relevant information on the submission form that accompanies the specimen. Drs. Boyd and Neldner12 have developed the “five D’s” mnemonic to remember the essential information to include on the requisition form:

Conclusion

The choice of biopsy technique can substantially affect the cosmetic result, the diagnostic information obtained, the time required to perform the procedure, and the cost. Shave, punch, curettage, incisional, and excisional biopsies each have advantages and disadvantages. (See Chapters 9, 10, and 11 for further information on these procedures.) Choosing among these biopsy techniques requires consideration of the size and morphology of the lesion in question, its anatomic location, the experience and skill of the physician, and the initial assessment of the diagnosis. It is of utmost importance that clinicians feel comfortable performing skin biopsies and, although it may not affect patient survival with a short delay between diagnostic biopsy and definitive treatment for melanoma, delaying the initial biopsy itself may have grave consequences.13

1. Bergfield WF, Pfenninger JL, Weinstock MA. Skin biopsy: selecting an optimal technique. Patient Care. 2001:11. March 30

2. Tran KT, Wright NA, Cockrell CJ. Biopsy of the pigmented lesion—when and how. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:852-871.

3. Achar S. Principles of skin biopsies for the primary care physician. Am Fam Physician. 1996;54:2411.

4. Oppenheim EB. Failure to biopsy skin lesions prompts litigation. Medical Malpractice Prevention. April 1990:5-6.

5. Molenkamp BG, Sluijter BJR, Oosterhof B, et al. Non-radical diagnostic biopsies do no negatively influence melanoma patient survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(4):1424-1430.

6. Ng PCJ, Garzilai DA, Ismail SA, et al. Evaluating invasive cutaneous melanoma: Is the initial biopsy representative of the final depth? Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(3):420-424.

7. McGovern TW, Litaker MS. Clinical predictors of malignant pigmented lesions: a comparison of the Glasgow seven-point checklist and the American Cancer Society’s ABCDs of pigmented lesions. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:22-26.

8. Lens MB, Nathan P, Bataille V. Excision margins for primary cutaneous melanoma. Updated pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Surg. 2007;142(9):885-891.

9. NIH Consensus Conference. Diagnosis and treatment of early melanoma. JAMA. 1992;268:10. 1314–1319

10. Greene MH, Clark WH, Tucker MA, et al. High risk of malignant melanoma in melanoma-prone families with dysplastic nevi. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:458-465.

11. Clark WHJr. The dysplastic nevus syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1207-1210.

12. Boyd A, Neldner K. How to submit a specimen for cutaneous pathology analysis. Arch Fam Med. 1997;6:64-66.

13. McKenna DB, Lee RJ, Prescott RJ, Doherty VR. The time from diagnostic excision biopsy to wide local excision for primary cutaneous malignant melanoma may not affect patient survival. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147(2):48-54.

Garcia C. Skin biopsy techniques (Chap 14). In: Robinson JK, Hanks CW, Sengelmann RD, Siegel DM, editors. Surgery of the Skin. Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2005.

Habif TP. Dermatologic surgical procedures (Chap 27). Clinical Dermatology, A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy, 4th ed. Mosby/Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2004.

Pfenninger JL. Skin biopsy (Chap 32). In: Pfenninger JL, Fowler GC, editors. Pfenninger and Fowler’s Procedures for Primary Care. Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2011.

Pfenninger JL. How to Perform Skin Biopsy: A Guide for Clinicians. Creative Health Communications www.creativehealthcommunications.com, 2005. Also available through the National Procedures Institute, www.npinstitute.com

Pfenninger JL. Common Office Dermatologic Procedures. Creative Health Communications www.creativehealthcommunications.com, 2005. Also available through the National Procedures Institute, www.npinstitute.com