Choose well, cut well, get well

This three-point dictum, probably coined in the early 20th century, was never intended as a simple three-step sequence. ‘Choose well’ extends throughout, leading the celebrated American surgical teacher Frank C. Spencer, to claim that good surgery is 20–25% manual dexterity and 70–75% decision-making.1

CHOOSE WELL

‘Not everything that counts can be counted and not everything that can be counted, counts.’

Notice on the Princeton University office wall of Albert Einstein

‘Choose well’, was originally directed only at the surgeon. The 1948 United Nations Declaration of Human Rights and subsequent legislation have emphasized the paramount rights of the fully informed patient2 to control what is done. Complex decisions, in particular those involving alternative or adjuvant (Latin: ad = to + juvare = to assist) therapies, intended to supplement effectiveness, are increasingly made at multidisciplinary meetings seeking a formalized consensus.

BACKGROUND KNOWLEDGE

1. Make decisions on the basis of critical reading of up-to-date reports, observation, copying successful colleagues, and following your patients in order to learn as you acquire experience. Test your decisions by presenting them to respected colleagues. As you organize the information you often recognize strengths and weaknesses.

2. Statistical analysis of the gathered experience from a large number of patients has profoundly influenced practice. Prospective, double-blind, controlled clinical trials, meta–analysis of the results of different studies,3 and application of Bayesian logic (a means of quantifying uncertainty as fresh information accumulates4), may offer guidance for treatment.

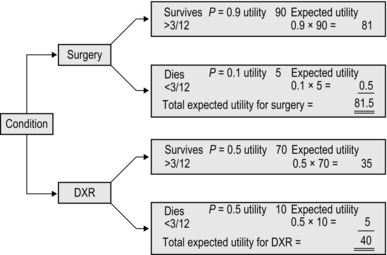

3. Decision analysis offers a means of weighing all the factors and possible outcomes5 (Fig. 1.1). The subjective assessments of satisfaction values are termed utilities, an unexpected term for anticipated benefit. Decision analyses are published for a number of common conditions. Computerized decision-support systems exist, offering advice and information which can be incorporated into subsequent judgements.6

4. The patient’s valuation must prevail, and patients may measure their satisfaction with treatment using criteria that differ from those of you, the surgeon. Dignity and quality of life weigh heavily with patients alongside life expectancy. A number of terms are used in assessing this: one measure is the quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).7 One year of life in perfect health is 1 QALY; a lower figure is allocated for a portion of a year in perfect health or a full year spent with a disability.

5. There are many general reviews such as evidence-based Cochrane Collaboration reports,8 and Clinical Knowledge Summaries commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence,9 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention10 and Health and Safety Executive.11

6. Economic cost–benefit analysis must be added, usually as a rule by economists and health management organizations.

7. In balancing variable evidence, numerical indicators are preferred over analogue terms because numbers can be manipulated and compared. Ensure that what is chosen to be measured is valid, and not selected merely because it can be assigned a number.

8. As new methods become available, conflicting evidence emerges about effectiveness and safety compared with existing practice. Enthusiasm of originators and early promoters of treatments may lead them to confuse placebo effect with successful treatment. In case of doubt, wait for confirmation from a source unconnected with inaugurating the procedure. The eminent London physician Sir William Whithey Gull (1816–1890) humorously and cynically stated, ‘Make haste and use all the new remedies before they lose their effectiveness.’

9. It is claimed that the tradition of doctors to customize treatments on an individual patient basis is detrimental to establishing the best method of management. Evidence-based medicine requires that fragmentation should be selectively replaced by standardization based on scientifically valid knowledge: an example cited is the success of well-vetted guidelines. Current methods of ranking outcome results for reporting to the public are imperfect, but transparency based on improved analyses should be the aim.12

10. ‘Choose well’ thus incorporates a complex challenge even before you face your patient.

INDIVIDUAL PATIENTS

1. In spite of increasing standardization and however much evidence is available, there are many factors that must be understood and negotiated with the patient (and often with multidisciplinary teams). Much of this information is subjective and may be difficult to identify, quantify or weigh. Each decision is a best guess, so it is valid only for the time it is made and must be flexible. Your initial plan is comparable to the strategy (Greek: stratos = army + agein = to lead; the overall plan) of a general before battle. Once battle is enjoined, he needs to monitor progress and alter his tactics (Greek: tassein = to arrange), responding to opportunities and threats.

2. We cannot always concentrate on a single patient when many people are ill. This is particularly true in wartime or following a civilian disaster. You must make urgent, sometimes agonizing, decisions. This process of triage (Old French = to pick, select) involves choosing to treat first those whose lives can be saved by quick action, whilst deferring treatment of those with peripheral, less lethal injuries: ‘Life comes before limb.’

3. Particularly in acute conditions, the features may change rapidly. Take your own history and only then read the existing notes and letters. They often differ. In case of doubt, when possible defer a decision. After an interval take a fresh history and thoroughly re-examine the patient. It is remarkable how often discrepancies are then revealed.

4. Do not be too proud to take advice. The very action of arranging and presenting the problem to another person often clarifies it.

5. Choose investigations carefully from those available after asking yourself ‘What do I expect to be revealed by the result?’ Prefer investigations that confirm or exclude a diagnosis, or clarify the extent of disease. Avoid ‘trawling’ – performing a battery of tests in the hope that something emerges: as the French chemist Louis Pasteur (1822–1895), stated, ‘Chance favours the prepared mind.’ If the results of investigations conflict with carefully and confidently obtained clinical findings, trust your clinical judgement. Many investigations are operator dependent: be prepared to confer with the person who has performed them.

LEARNING

1. Even if you are a trainee, not permitted to make and act on your decision, do not ignore the opportunity to increase your experience. Commit yourself: mentally consider the possible options as though you do have the responsibility and are defending your proposed course of action. Follow the patient to determine the outcome. Do not be an onlooker – learn from the encounter.

2. Try to consider the possibilities – the ‘what ifs… .’ and how you would modify your management in each circumstance. Take up every opportunity to present your decision and be willing to offer the evidence to justify it.

CUT WELL

It is estimated that approximately 230 million surgical procedures are performed each year worldwide.13 Operative techniques are undergoing remarkable changes as the result of technological improvements, particularly in three-dimensional imaging and minimally invasive surgery, which permits improved access to the target structures requiring surgical intervention while causing minimal damage to the interposed tissues. Many previously sacrosanct ‘rules’ of procedure no longer apply, but one tradition remains inviolate. Following the successful demonstration of general anaesthesia with inhaled ether in 1846 and the development of antiseptic, then aseptic, surgery from 1867, three visionary surgeons and friends, Theodore Kocher of Berne (1841–1917), William Halsted of Baltimore (1852–1922) and Harvey Cushing of Yale (1869–1939), pioneered the era of gentle, deliberate, aseptic, painstakingly haemostatic technique, completed with accurate apposition of viable, tension-free tissues. All subsequent technological refinements are merely instruments designed to reduce to a minimum the threat to living tissues. You cannot make the tissues heal but your disregard for them can prevent them from doing so.

Your commitment to performing operations carefully and skilfully does not appear automatically as you enter the operating theatre. You bring it with you, by acquiring the habit in everyday life of striving to perform every activity carefully, faultlessly and to completion, so that it becomes second nature.14

PREPARE

1. Make sure that the patient is correctly identified, labelled and listed.

2. Re-assess the condition requiring surgery and check for any previous operations – and any untoward reactions. Identify and personally mark unilateral conditions.

3. Obtain a list of routine drugs being taken.

4. Identify any co-morbidity such as infection, diabetes, allergies or drug reactions.

5. In appropriate circumstances screen the cardiorespiratory, peripheral vascular, haematological, urogenital, endocrine, digestive and neurological systems. Check the nutritional state and fluid and acid-balance.

6. If the patient will require special treatment postoperatively, for example care of a stoma or a limb prosthesis, they should receive preoperative specialist instruction and reassurance.

7. Check the psychological state.

8. Make sure that the patient gives informed consent.

9. Arrange for appropriate corrections to be made to make the patient fully fit for surgery, including prophylactic antibiotics, prevention of thrombo-embolic complications, necessary modifications in the presence of prostheses and dealing with conditions normally treated with regular drugs.

10. Arrange for preparations appropriate to the procedure, such as bowel preparation. Shaving is employed much less frequently than formerly and is usually carried out immediately preoperatively or replaced by the use of depilatory preparations.

PRACTISE

1. It is now widely accepted that as far as possible you should find alternative methods of learning skills before performing them on patients. Attend courses, operate on simulations, virtual reality trainers, and the tissues of cadavers or dead animals to gain familiarity with the necessary sequence of activities. Use every opportunity to develop your skills to the point where you automatically perform each action gently and accurately. In many countries, including the United Kingdom, you are permitted to operate on living animals to practise technique only in exceptional circumstances, but even in countries where practice on anaesthetized living animals is permitted you cannot replicate the textural changes produced by disease and injury. These artificial representations are imperfect but they offer practice in familiarizing yourself with the instruments and equipment. When you operate on patients, your attention can be focused on the target structures, since you can relegate the manipulation of instruments to a subsidiary focus.15

2. Assiduously watch experts and copy them. Concentrate not only on the limited area of the procedure but also observe the peripheral details. Practise the manoeuvres. Practice is different from exercise, which is repeating the same manoeuvre over and over until it becomes automatic: this precludes improvement. In contrast, during practice each attempt differs from the last, to determine if it can be improved, made smoother, feel more natural or more perfect. Only then is it converted into an exercise. Musicians and instrumentalists, even at the peak of their careers, continuously practise to improve their technique and to identify and correct acquired bad habits.16

3. Even if you are already highly skilled, do not despise creating a simple simulation in order to perfect an otherwise difficult manoeuvre. Again, note that professional musicians are willing to practise challenging sections right up to the moment of performance. Lord Moynihan (1865–1936), much admired for his gentle technique, always carried a length of thread with which he practised tying knots with consummate perfection.

4. Know the anatomy. Learn it thoroughly, not just from books but by every available means. Know it extensively and in three dimensions, not just locally.

5. Exploit your acquired knowledge of inter-related structures and the (usually potential) spaces between them. Avoid wandering inadvertently away from the target structures but, in contrast, gain in confidence when you need to explore away from them.

6. Be aware that the planes of contact change between structures as a result of postural changes.

7. Handle living tissues with meticulous gentleness. Every thoughtless grasp, even with fine dissecting forceps, exerts a powerful crushing force per unit area.

8. Scrupulously observe the best aseptic techniques.

9. Achieve and maintain absolute haemostasis while avoiding excess burning, strangulation of tissue and insertion of foreign materials.

10. Appose the tissues perfectly with the minimum distortion and constriction.

11. Be aware that visual assessment of tissue vitality is notoriously unreliable. When wounds are closed, within the now closed compartment the interstitial oxygen concentration falls initially.17,18

SET UP

1. Inexperienced and overconfident surgeons, anxious to demonstrate that they are expeditious, rush to start the operation. Do not. Carefully check that you have all the components required for smooth, calm, progression. Ask yourself again:

2. As soon as you expose the operation site, stop and gently assess the situation. In the presence of susceptible infection or neoplasia, start at a distance and work towards the diseased centre in order to avoid spreading micro-organisms or malignant cells.

3. Do not proceed until you are confident in your decision and your ability to achieve your intention.

IMPROVE PATIENT SAFETY

Healthcare has traditionally been proudly delivered on an individual basis. The variations of treatment make it difficult to compare outcome results. Powerful arguments are now advanced for acceptance of standardized methods of delivering healthcare to facilitate measurement, with general adherence to the proven most successful methods. When scientifically validated standardized treatments are available, rigid adherence to treating each patient on an individual basis is compared with cottage industry practice.12

It is estimated that the perioperative death rate is 0.4–0.8% and that at least half of these deaths are avoidable.20 Adverse events must be reported, often with the hope of modifying the system rather than merely blaming the operator.21 With the intention of reducing errors, checking of action sequences is being widely and rapidly introduced (WHO Guidelines for Safe Surgery):22

1. When preparing to perform an emergency procedure, do not rush to get started before you have calmly and fully considered what you should do, how you intend to achieve your objective, what essential equipment you will require and whether it is in proven working order. Have you considered the possibilities of unexpected findings and difficulties, and how will you deal with them?

2. Consider if your decision can be modified with the help of carefully selected available investigations.

3. Should you make written and photographic records of the preoperative situation?

4. Do not hurry for any reason that you cannot fully justify. When you hurry, the skilful actions that you have learned to perform perfectly and automatically are transferred to your conscious focus, distracting your prime concentration from awareness of the whole situation. You can demonstrate this to yourself: type information hurriedly into your computer and note the rise in the error rate – you become clumsy.

5. As you perform an emergency operation, never lose sight of your intentions. Carry out the procedure that will, as simply and safely as possible, correct the problem for which you embarked on the operation. Do no more unless you encounter a new threat. Subsidiary and unnecessary ‘just in case’ actions are potent causes of complications.

6. As you proceed through the operation, performing the required actions partly in series, partly in parallel, remember that within the sequence of complex decisions and actions, it needs but one imperfect component to threaten the success of the procedure. For example, once you think you have identified a structure it is tempting not to challenge the assumption. During laparoscopic surgery in particular, misperception has been identified as a potent contributor to errors.23

7. Never relax your vigilance over the wound, instruments, swabs and other materials placed into the wound. Use as few swabs as possible and always use the largest ones compatible with the task. Avoid burying all of a swab or pack in the wound; leave a portion, or attached tape, protruding to be clipped to the wound towels. There is no single, once-and-for-all action that will prevent articles from being left inside: check everything, every time. Involve as many others as possible in the check: they may save you from a momentary lapse.

8. If you repeatedly encounter difficulty and have to rectify it, what steps have you taken to ensure that you confidently perform smoothly and faultlessly at the next initial attempt?

PREVENT OR COMBAT INFECTION

1. Surgical infection is not static and changes continuously as a result of multiple factors. Ensure you are aware of current practice by frequently consulting the bacteriologists and regularly searching the published literature including bulletins from the Health Protection Agency and the Surgical Site Infection Surveillance Service.24,25

2. Standard practices to combat infection are complimented by the skill with which you operate, reducing trauma, tissue de-vitalization and contamination to a minimum.

3. Wounded tissues resist infection with non-specific immunity provided by neutrophils. These cells depend on a high partial pressure of oxygen, from which superoxides are catalysed in their cellular membranes, and these are bactericidal. Wound oxygen tension depends on full blood perfusion and high arterial oxygen partial pressure. It is reduced by vasoconstriction, as from exposure to cold, sympathomimetic effects, including failed pain relief and by hypovolaemia. The use of peri-operative high fractional inspired oxygen has been reported to be beneficial.26

4. Administer prophylactic antibiotics 30 minutes before the operation in order to gain the highest level of protection.

GET WELL

1. You have not yet fulfilled your commitment to the patient when you have completed the correct operation skilfully. In former circumstances a familiar team would take over the care of the patient. Teams now work in timed shifts and those who replace the ones you have advised need to receive written instructions that they can consult and pass on. Clearly and fully record what should be monitored, what to expect and how to react. Organize aftercare meticulously or risk undoing the benefits of all your preceding planning and efforts.

2. Always make a full record as soon as possible of the operative findings, giving details of the procedure carried out and any special points such as the insertion of drains. Be prepared to provide a sketch of the incisions and of attached drains, cannulae or other apparatus, with instructions about the management of each one: in complicated cases ensure that drains are labelled.

3. Especially following a major operation, or one carried out on a poor-risk patient, inform the relatives and the general practitioner as soon as it is convenient, personally or by telephone. It is usually best to defer passing on the full impact of distressing news to relatives until you can speak under less stressful circumstances.

RECOVERY PHASE

Monitor

1. Airway, Breathing, Circulation (ABC) are vital functions to observe during the recovery from anaesthesia.

2. Regularly review the pulse, blood pressure chart, respiration rate and temperature chart to pick up the trend.

3. Order frequent checks of the consciousness level by noting the response to stimuli, such as calling the patient’s name. In case of doubt ask for pupillary and other reflexes and peripheral muscular tone to be tested.

4. Do not take a fixed attitude to the amount of pain the patient is likely to suffer. Order small, repeated doses of analgesics if the recovering patient suffers pain.27

5. Give appropriate orders for checks of the wound and drains, especially if blood emerges from an abdominal or chest drain.

6. Restlessness of the patient may have other causes than wound pain, such as an overfilled bladder, uncomfortable position or pressure from sharp or hard apparatus.

7. Ensure that as soon as the patient is responsive they are given information, which is as reassuring as possible, about the operation and the present situation.

8. The wakened patient needs to breathe deeply, cough and exercise the legs within the limits posed by the procedure.

INTERMEDIATE PHASE

1. Regularly check not only the patient but also the pulse, temperature and respiration rate.

2. Mobilize the patient as quickly as possible. Order breathing and coughing exercises, leg and foot movement to reduce venous stasis, frequent changes of posture and walking as soon as possible.

3. Achieve and maintain fluid, electrolyte and acid–base balance and nutritional requirements.

4. Frequently check the wound, infusion sites, drains and the function of the system subjected to operation.

5. Bear in mind co-morbidities including insulin-dependent diabetes, depression, drug abuse and long-term therapeutic drugs. Patients with prosthetic heart valves who are temporarily on heparin usually require warfarin therapy to be reinstated postoperatively.

6. If the patient’s condition deteriorates, first carry out a thorough systematic examination and carefully selected investigations. Do not restrict your survey to the operative condition and thereby miss an overlooked co-morbidity.

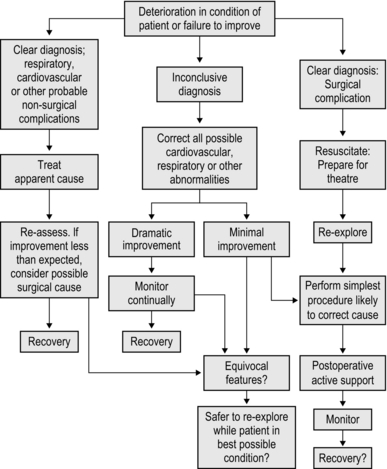

7. If you initiate non-specific supportive treatment and the patient improves do not assume that the problem is solved. Placebo effects may mislead you. Remain vigilant and anticipate possible deterioration (see Fig 1.2).

DAY CASE SURGERY

1. Monitor the recovery from a general anaesthetic as thoroughly as for an inpatient. Sedation with benzodiazepines and administration of analgesics may depress respiration: monitor breathing rate and depth for 2 hours.

2. Even though you are compressing the assessment of recovery into a shorter period, ensure that the cardiovascular and respiratory functions are normal before discharging the patient.

4. Fully inform the patient of the procedure, the likely sequelae, danger signs and what to do about them. If possible, give written instructions for later reference.

5. If a follow-up appointment is to be given, arrange it now.

6. Ensure that those who have had a general anaesthetic or sedation are accompanied home.

7. Record the findings and procedure immediately. Day case patients are often admitted, treated, monitored and discharged in sequence. It is easy to confuse their details if these are not recorded individually between procedures.

AUDIT

1. Well organized audit (Latin: audire = to hear; a hearing, a trial) is a powerful driver for improvement. Identifying problems is only the beginning of the process: it is vital that this is followed by solutions. ‘Closing the circle’ describes the need to identify why outcomes are poor, what practical solutions can be implemented, implementing them – and demonstrating that the introduction has corrected the results.28

2. The improvement achieved by the Great Britain and Ireland Society of Cardiac Surgeons is remarkable.29 They have compiled a database of 400 000 patients over a 15-year period, demonstrating a 21% reduction in mortality when compared to previous outcomes. In particular, they have devised methods of incorporating and accounting for many of the variations from standard scenarios, and have thrown down a challenge to the remainder of surgical specialties to achieve comparable success in surveillance and transparency.

REFERENCES

1. Spencer, F.C. Teaching and measuring surgical techniques – the technical evaluation of competence. Bull Am Coll Surg. 1978; 63:9–12.

2. Doyal, L. Consent for surgical treatment. In: Kirk R.M., Ribbans W.J., eds. Clinical Surgery in General. 4th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2004:155–164.

3. Ng, T.T., McGory, M.L., Ko, C.Y., et al. Meta–analysis in surgery: methods and limitations. Arch Surg. 2006; 141:1125–1130.

4. Freedman, L. Bayesian statistical methods. BMJ. 1996; 313:569–570.

5. Kirk, R.M., Cox, K. Decision making. In: Kirk R.M., Ribbans W.J., eds. Clinical Surgery in General. 4th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2004:144–151.

6. Wyatt, J.C. Decision support systems. J R Soc Med. 2000; 93:629–633.

7. Langenhoff, B.S., Crabbe, P.F.M., Wobbes, T., Ruers, T.J.M. Quality of life as an outcome measure in surgical oncology. Br J Surg. 2001; 88:643–652.

9. www.nice.org/search/guidance.

12. Swenson, S.J., Mayer, G.S., Nelson, E.C., et al. Cottage industry to post-industrial care – the revolution in health care delivery. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362:e12.

13. Weiser, T.G., Regenbogen, S.E., Thompson, K.D., et al. An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modelling strategy based on available data. Lancet. 2008; 372:139–144.

14. Kirk, R.M. Basic Surgical Techniques, 6th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

15. Polanyi, M. Two Kinds of Awareness. In: Personal Knowledge. London: Routledge and Keegan Paul; 1958:55–57.

16. Kirk, R.M. Surgical skills and lessons from other vocations. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006; 88:95–98.

17. Chang, N., Goodson, W.H., III., Gottrup, E., Hunt, T.K. Direct measurement of wound and tissue oxygen tension in postoperative patients. Annals Surgery. 1983; 197:470–478.

18. Ueno, C., Hunt, T.K., Hopf, H.W. Using physiology to improve surgical wound outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006; 117(7S):595–715. [Supplement].

19. O’Neil, O., A question of trustThe Reith Lectures 2002. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

20. Gawane, A.A., Thomas, E.J., Zinner, M.J., et al. The incidence and nature of surgical adverse events in Colorado and Utah in 1992. Surgery. 1999; 126:66–75.

21. Reason, J. Human error; models and management. BMJ. 2000; 320:768–770.

22. WHOGuidelines for Safe Surgery 2009: safe surgery saves lives. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009.

23. Way, L., Stewart, L., Gantert, W., et al. Causes and prevention of laparoscopic bile duct injuries: analysis of 252 cases from a human factors and cognitive psychology perspective. Annals Surgery. 2003; 237:460–469.

25. Reilly, J., Kilpatrick, C. Preventing surgical wound infection: evidence based practice for surgical wound care. Nurse 2 Nurse. 2002; 2:47–50.

26. Greif, R., Akca, O., Horn, E.-P., et al. Supplemental peri-operative oxygen to reduce the incidence of surgical wound infection. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:161–167.

27. Sodhi, V., Fernando, R. Management of postoperative pain. In: Kirk R.M., Ribbans W.J., eds. Clinical Surgery in General. 4th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2004:357–369.

28. Davidson, B., Schneider, H.J. Audit. In: Kirk R.M., Ribbans W.J., eds. Clinical Surgery in General. 4th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2004:428–436.

29. Bridgewater B, Kinsman R, Walton P, Keogh B. UK ‘Blue Book’@ 2009. The 6th National Adult Cardiac Surgical Database Report. Oxon: Dendrite Clinical Systems; 2010. ISBN:1-903968-23-2.