Chapter 32 CHOLESTASIS AND JAUNDICE

CAUSES OF CHOLESTASIS

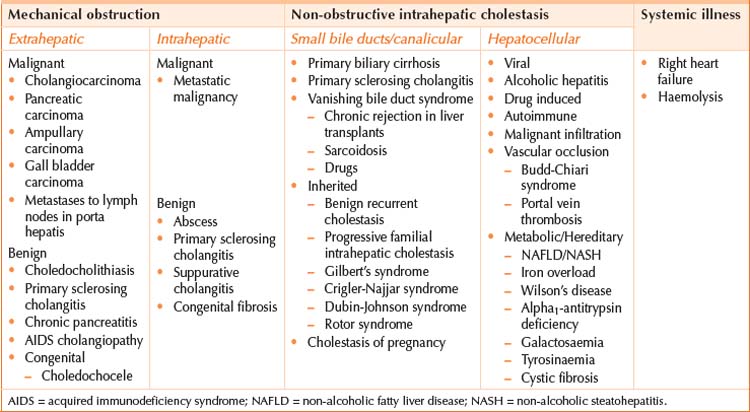

Cholestasis can broadly be divided into that caused by mechanical obstruction, and that caused by non-obstructive or hepatocellular causes. Table 32.1 lists the causes of cholestasis. Mechanical obstruction may develop in either the extrahepatic biliary tree or the smaller intrahepatic bile ducts. Non-obstructive intrahepatic cholestasis may arise from parenchymal disease affecting the small bile ducts and canaliculi or conditions affecting the hepatocytes directly (causing an excess of bile products to be formed). Considering the possible underlying causes of cholestasis will guide the history, examination and investigation of a patient with cholestasis. Important causes to consider include the following.

ASSESSMENT

History

Specific questioning will help determine the underlying aetiology of the cholestasis.

Physical examination

Check for shifting dullness (ascites), which, if present, suggests hepatic decompensation.

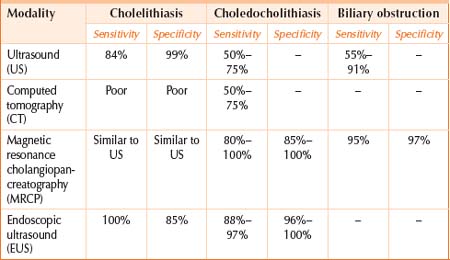

Investigations

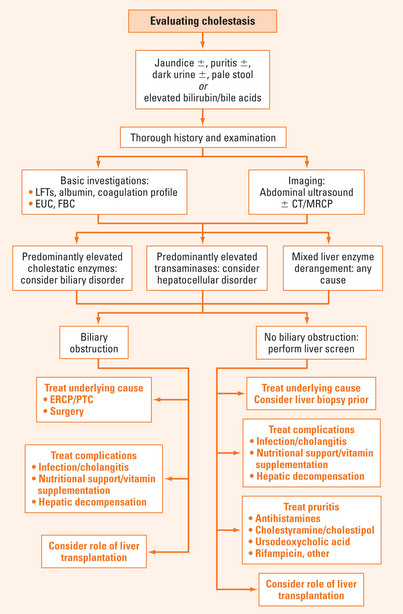

Basic laboratory tests: biochemistry (liver function tests, electrolytes and creatinine), full blood count and coagulation profile. Note the degree of hyperbilirubinaemia and the presence of hypoalbuminaemia and coagulopathy (which together suggest hepatic decompensation). Disorders of the bile ducts predominantly cause elevation in gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT) and alkaline phosphates (ALP). In disorders affecting hepatocytes, the serum transaminases (alanine aminotransferase [ALT] and aspartate aminotransferase [AST]) predominantly may be elevated. There is often mixed liver function test derangement, in which case further investigations may be necessary to narrow the differential diagnosis (see Chapter 30).

Invasive imaging modalities (with therapeutic capability)

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC)

This ultrasound-guided procedure is an alternative or adjunct in patients who will not tolerate ERCP, or in those patients in whom ERCP is technically difficult (e.g. in cases of non-dilated biliary system or abnormal anatomy). Biliary stenting and percutaneous biliary drainage is also possible with this method.

Liver screen

Liver biopsy

Percutaneous liver biopsy is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of liver disease. A liver biopsy may be necessary before committing a patient to specific treatments with significant adverse effects or toxicity. Liver biopsy is also useful to determine disease severity and prognosis by evaluating extent of fibrosis or cirrhosis. Specialty consultation should be considered before a liver biopsy because of the risks associated with the procedure (see Chapter 33).

MANAGEMENT

TABLE 32.3 Mechanism of action of drugs to manage cholestasis

| Cholestyramine | Cholestyramine resin combines with bile acids forming a complex that is excreted in the faeces. This non-systemic action results in a partial removal of the bile acids from the enterohepatic circulation, preventing their reabsorption |

| Colestipol | An oral hypolipidaemic that binds bile acids in the intestine, i.e. works like cholestyramine |

| Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) | A hydrophilic bile acid. The assumption is that replacing the bile acid pool UDCA may reduce hepatocyte damage |

| Rifampicin | May decrease pruritus by competing with bile acids for hepatic uptake, thereby minimising bile acid toxicity to the hepatocyte. May also induce microsomal enzymes that promote 6-alpha-hydroxylation and subsequent glucuronidation of toxic bile salts |

| Phenobarbitone | Sedative properties |

| Opioid antagonists | Opiate receptors may be implicated in pathogenesis of pruritis therefore blocking these receptors theoretically may improve symptoms |

Liver transplantation should also be considered in refractory cholestatic pruritis.

SUMMARY

Both cholestasis and jaundice can arise due to biliary, hepatocellular and systemic conditions. Biochemical clues may suggest the underlying mechanism for the cholestasis: elevated bilirubin and cholestatic enzymes (ALP and GGT) suggest a biliary cause; elevated bilirubin and transaminases (ALT and AST) suggest a hepatocellular cause (Figure 32.1). Imaging with abdominal ultrasound gives useful information about both the underlying cause for cholestasis and any complications of liver disease. A full liver screen will narrow the differential diagnosis for cholestasis. Treatment of cholestasis is primarily aimed at treating the underlying cause, but a range of symptomatic treatments is available. In particular, pruritus is a troublesome symptom of cholestasis, and can occur with elevated bile acids, even when the bilirubin is within normal range.

Balistreri WF, Bezerra JA, Jansen P, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis: summary of an American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases single-topic conference. Hepatology. 2005;42:222-235.

Demery PA, Seidman DS, Stevenson DK. Neonatal hyperbilirubinaemia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:581-590.

Glantz A, Marschall HU, Mattsson LA. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: relationships between bile acid levels and fetal complication rates. Hepatology. 2006;40:467-474.

Glasova H, Beuers U. Extrahepatic manifestations of cholestasis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:938-948.

Kaplan MM, Gershwin ME. Primary biliary cirrhosis. N Eng J Med. 2005;353:1261-1273.

Levy C, Lindor KD. Drug-induced cholestasis. Clin Liver Dis. 2003;7:311-330.