Choledochal Cyst and Gallbladder Disease

Choledochal Cyst

Choledochal cyst is a congenital dilatation of the biliary tract. The dilatation can be found along any portion of the biliary tract. However, the most common site is the choledochus. The diameter of the bile duct varies according to the child’s age.1–3 Normal diameter of the common bile duct (CBD) is seen in Table 44-1.2 Any diameter of the bile duct greater than the upper limit should be considered abnormal.

TABLE 44-1

The Mean Common Bile Duct Diameter and the Range According to a Patient’s Age

| Age (Years) | Range (mm) | Mean (mm) |

| ≤4 | 2–4 | 2.6 |

| 4–6 | 2–4 | 3.2 |

| 6–8 | 2–6 | 3.8 |

| 8–10 | 2–6 | 3.9 |

| 10–12 | 3–6 | 4.0 |

| 12–14 | 3–7 | 4.9 |

Adapted from Witcombe JB, Cremin BJ. The width of the common bile duct in childhood. Pediatr Radiol 1978;7:147–9.

Classification

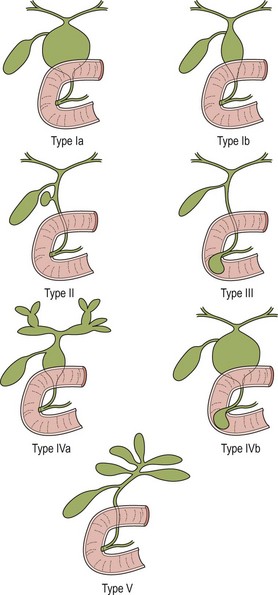

Different classifications have been proposed for choledochal cyst.4–8 However Todani’s classification has been the most widely accepted (Fig. 44-1).5 According to this classification, choledochal cyst (CC) are classified into five types:

FIGURE 44-1 These diagrams depict the five classifications for choledochal cyst according to Todani. (From Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, et al. Congenital bile duct cyst: Classification, operative procedure, and review of 37 cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg 1977;134:263–9.)

• Type II: diverticulum of the CBD

• Type III: choledochocele (dilatation of the terminal CBD within the duodenal wall)

• Type V—intrahepatic duct cyst (single or multiple, as in Caroli disease).

Forme fruste is a special variant of choledochal cyst characterized by pancreaticobiliary malunion, but little or no dilatation of the extrahepatic bile duct.8–12 Children present with symptoms similar to those in patients with a CC. Excision of the extrahepatic bile duct is recommended in children because of the likely eventual development of cancer due to chronic pancreaticobiliary reflux.

Type I CCs predominate. Together with type IVa cysts, they account for more than 90% of cases. Caroli disease is characterized by segmental saccular dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts. It may affect the liver diffusely or be localized to one lobe.13–15

Etiology

There are many theories to explain the development of a CC. However, none of these can explain the formation of the five different types of CC. Choledochal cysts seem to be either congenital or acquired. Congenital cysts develop during fetal life.16 These appear to develop as a result of a prenatal structural defect in the bile duct. Shimotake found that the total number of ganglion cells within the wall of these CCs is significantly lower than in control specimens.17 Also, smooth muscle fibers are more abundant in the cystic type than in the fusiform type.18

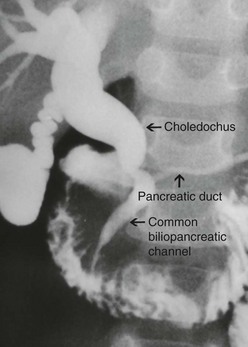

Choledochal cysts which develop later in life are considered ‘acquired’.16 The theory of the long common biliopancreatic channel proposed by Babit has been widely accepted to explain the formation of this type.19 Normally, the terminal CBD and pancreatic duct unite to form a short common channel, which is well surrounded by Oddi’s sphincter. This normal anatomic arrangement prevents the reflux of pancreatic fluid into the bile duct. If this common channel is long and part of it is not surrounded by the normal sphincter, pancreatic secretions can reflux into the biliary tree (Fig. 44-2). Proteolytic enzymes from the pancreatic fluid are activated and can cause epithelial and mural damage that leads to mural weakness and dilatation of the choledochus. This theory is supported by the fact that high concentrations of activated pancreatic amylase and/or lipase have been found in patients with CC and long pancreaticobiliary channels.16,20–22 In an experimental study, CC was produced by creating a choledochopancreatic end-to-side ductal anastomosis.23 Also, a high incidence of a common channel has been detected in CC patients.24

FIGURE 44-2 This contrast study depicts a long common biliopancreatic channel which allows reflux of pancreatic secretions into the biliary tree. A long common biliopancreatic channel is thought to be the etiology of an acquired choledochal cyst.

Obstruction at the level of the pancreaticobiliary junction may be an associated causal factor in choledochal dilatation. An experimental model for the study of cystic dilatation of the extrahepatic biliary system has been produced by ligation of the distal end of the CBD in the newborn lamb.25 High biliary pressure in patients with CC have also been recorded during operative correction.26

In adults, an anomalous union of the pancreaticobiliary duct is defined when the common pancreaticobiliary channel is longer than 15 mm,3,27 or when its extraduodenal portion is more than 6 mm.28 In a study of 264 infants and children undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), the maximal length of the common channel was found to be 2–7 mm among children ≤ 3 years old, 4 mm among children 4 to 9 years old, and 5 mm between 10 and 15 years old.29

Clinical Features

Females are affected more often than males. In our series of 400 cases, the female to male ratio was 3.2 to 1.30 Clinical presentations differ according to the age of onset and the type of cyst. An abdominal mass or jaundice is a common finding in an infant with CC, whereas abdominal pain is more often seen in older children.16,31–33 The cystic form usually presents with an abdominal mass whereas the fusiform type is usually found in patients presenting with abdominal pain. Choledochal cysts diagnosed antenatally are more likely cystic in nature.16

Clinical manifestations among our 400 cases included: abdominal pain (88%), vomiting (46%), fever (28%), icterus (25%), discolored stool (12%), abdominal tumor (7%), and the classic triad (2%).30

Complications such as perforation and hemobilia are rare;34,35 however pancreatitis is common.16,31 Malignant change is a late complication, mostly seen in adults.36–39

Imaging

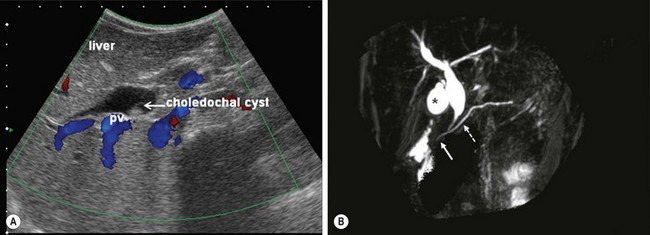

Ultrasonography (US) is the initial imaging method of choice (Fig. 44-3A). Contour and position of the cyst, the status of the proximal ducts, vascular anatomy, and hepatic echotexture can all be evaluated on ultrasound.

FIGURE 44-3 (A) Ultrasound is the initial imaging method of choice for identifying a choledochal cyst. The cyst is identified as well as the portal vein (PV) lying posterior to it. (B) MRCP is highly accurate in the detection and classification of the cyst. On this MRCP image, note the fusiform choledochal cyst as well as the pancreatic duct (dotted arrow) and long common channel (solid arrow). The gallbladder is marked with an asterisk.

ERCP allows excellent definition of the cyst as well as the entire anatomy, including the pancreatobiliary junction. However, this investigation is invasive and has complications such as pancreatitis, perforation of the duodenal or biliary tracts, hemorrhage, and sepsis.40,41

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is highly accurate in the detection and classification of the cysts. (Fig. 44-3B) The overall detection rate of MRCP for a CC is very high (96–100%) and should be considered a first-choice imaging technique for evaluation.42–44

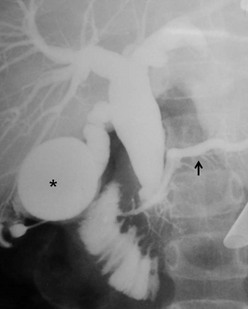

Intraoperative cholangiography is indicated when the anatomic detail of the biliary tract cannot be demonstrated by MRCP or ERCP (Fig. 44-4). Contrast-enhanced CT may be indicated in some patients with pancreatitis or if an associated tumor is suspected.

FIGURE 44-4 In this patient, neither an MRCP nor ERCP were helpful preoperatively. Thus, an intraoperative cholangiogram was performed to identify the anatomic detail within the biliary tract. The distended gallbladder is marked with an asterisk. The enlarged choledochal cyst is seen and the pancreatic duct is identified with a solid arrow.

Surgical Techniques

General Principles

Cystoduodenostomy and cystojejunostomy have been abandoned due to cholangitis, stone formation, and malignant degeneration.6,45–47 External drainage is indicated for a perforated cyst in patients whose condition is too unstable to perform cystectomy and a bilio-enteric anastomosis.34,35

Cyst excision and a bilio-enteric anastomosis is the preferred approach for most patients. The cyst should be excised at the level of the common biliopancreatic channel orifice at its distal end and approximately 5 mm from the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts at the proximal end. Postoperative malignancy in a residual cyst on either hepatic duct side or from the distal part has been reported.48,49 A review from the English language and Japanese literature of 23 patients with carcinomas of the bile duct developing after CC excision found that malignancy developed in the intrapancreatic remnant of the bile duct or CC in six patients, in the remnant of the CC at the hepatic side in three patients, in the hepatic duct at or near the anastomosis in eight patients, and in the intrahepatic duct in six patients.48 Abdominal pain and pancreatitis due to leaving a remnant of the cyst in the pancreatic head has also been described.50

Operative correction can be performed safely in all age groups.30,51–53

Bilio-Enteric Anastomosis after Cystectomy

Many surgeons use hepaticojejunostomy54–59 while others prefer hepaticoduodenostomy.60–64 Fat malabsoption and duodenal ulcer are the main concerns with a hepaticojejunostomy. In addition, the operative time is longer in comparison with hepaticoduodenostomy. Complications after Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy such as a twist of the Roux limb, intestinal obstruction, and duodenal ulcers have been reported.65–68 On the other hand, cholangitis and gastritis due to bilious reflux are the main concerns with hepaticoduodenostomy.69,70 However, the operative time is shorter in comparison with hepaticojejunostomy. A hepaticoduodenostomy is considered more physiologic because the bile drains directly into the duodenum. This anastomosis is performed above the transverse colon mesentery which may help prevent intestinal obstruction from adhesions.

Laparoscopic Approach

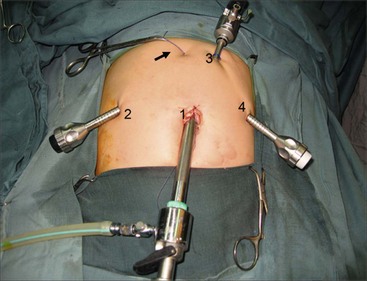

Endotracheal intubation general anesthesia is standard. Epidural analgesia can provide excellent postoperative pain relief. Broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics are best given at induction of anesthesia and continued for five days postoperatively. A nasogastric tube, rectal tube, and urinary catheter are used to decompress the stomach, colon, and bladder. The patient is placed in a 30° lithotomy position (Fig. 44-5). The surgeon stands at the lower end of the operating table between the patient’s legs.

FIGURE 44-5 Older patients are placed in the lithotomy position and smaller patients are moved to the end of the bed. It is helpful for the surgeon to stand either between the patient’s legs (in older patients) or at the end of the operating table (in younger patients) for laparoscopic choledochal cyst repair.

The first laparoscopic operation for CC was reported in 1995.71 This approach quickly became popular and has become a routine procedure in many centers.30,72–84 The laparoscopic approach is preferred for most types of CC: I, II, and IV. Relative contraindications are in patients with perforation, previous biliohepatic surgery, or especially newborns with damaged hepatic functions.

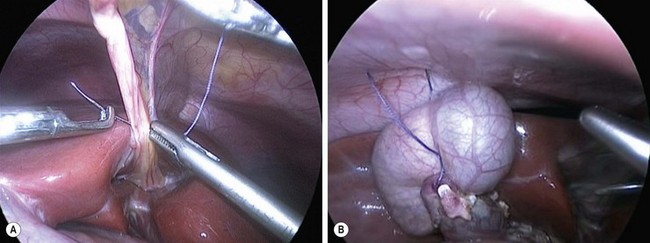

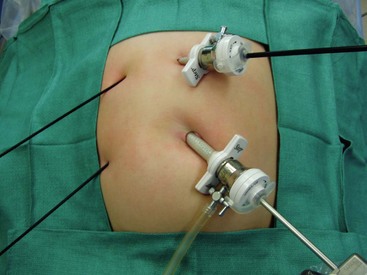

A 10 mm cannula is inserted through the umbilicus for the telescope. Three additional 5 or 3 mm ports are introduced for the working instruments: one in the right flank, another in the left flank, and one in the left hypochondrium (Fig. 44-6). Carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum is maintained at a pressure of 8–12 mmHg. The liver is secured to the abdominal wall with a suture placed around the round ligament (Fig. 44-7A). The cystic artery and the cystic duct are identified, clipped, and divided. A second traction suture is placed at the junction of distal cystic duct and gallbladder fundus to elevate the liver and expose the hepatic hilum (Fig. 44-7B).

FIGURE 44-6 This operative photograph depicts placement of the ports for laparoscopic repair of a choledochal cyst. A 10 mm cannula (1) is introduced through the umbilicus for the telescope. Three additional 5 mm or 3 mm ports are then used for the working instruments (2,3,4). Note the liver has been elevated anteriorly with a suture placed around the round ligament and exteriorized in the epigastric region (arrow).

FIGURE 44-7 (A) Suture has been placed through the round ligament and will be exteriorized in the epigastrium in order to help elevate the liver for exposure of the choledochal cyst. (B) A second traction suture has been positioned at the junction of the distal cystic duct and gallbladder fundus to further elevate the liver anteriorly and expose the hepatic hilum.

The inferior part of the cyst is separated from the pancreatic tissue down to the common biliopancreatic duct using a 3 mm dissector for cautery and dissection. Protein plugs or calculi within the cyst and common channel are washed out and removed. The inferior part of the cyst is opened longitudinally and inspected to identify the orifice of the common biliopancreatic channel. A small catheter is then inserted into the common channel. Irrigation with normal saline via this catheter is performed to eliminate protein plugs until clear fluid returns and the catheter can be passed down into the duodenum (Fig. 44-8A). A cystoscope can be used to remove protein plugs in the common channel if its diameter permits.85,86 The distal CC is then clipped and divided at the level of the orifice of the common channel (Fig. 44-8B).

FIGURE 44-8 (A) After opening the inferior part of the cyst to identify the orifice of the common biliopancreatic channel, a small catheter is inserted into the common channel for irrigation and elimination of protein plugs. (B) After irrigating the common channel, the distal choledochal cyst is being ligated with an endoscopic clip and will subsequently be divided at the level of the orifice of the common channel.

The cephalad portion of the cyst is further dissected to the common hepatic duct. The cyst is initially divided at the level of the cystic duct. After identifying the orifice of the right and left hepatic ducts, the rest of the cyst is removed, leaving a stump approximately 5 mm from the bifurcation of the hepatic ducts. Irrigation with normal saline through a small catheter inserted into the right and then into the left hepatic duct is performed to wash out protein plugs or calculi until the effluent is clear.

Hepaticojejunostomy

The Roux limb is passed through a window in the transverse mesocolon to the porta hepatis. The jejunum is opened longitudinally on its antimesenteric border a few millimeters from the end of the Roux limb to avoid the creation of a significant blind pouch as the child grows. The hepaticojejunostomy is fashioned using two running sutures of 5-0 PDS (interrupted sutures are used when the diameter of the common hepatic duct is less than 1 cm). The anastomosis is performed from left to right using 3 mm instruments. If the diameter of the common hepatic duct is too small, ductoplasty is performed by opening the common hepatic duct and incising the left hepatic duct longitudinally for a variable distance.

Alternative Operative Techniques

An alternative biliary reconstruction technique is an end-to-end hepaticojejunostomy (in contrast to end-to side). This should only be performed if there is no significant size discrepancy between the hepatic duct and Roux limb. A hepaticoduodensotomy with jejunal interposition can be performed if desired. The robotic approach has also been described.87,88 This technique appears safe and effective, but the operative time is quite long.

Postoperative Care

Complications from the laparoscopic approach are similar or lower when compared to the open operation.89,90 Early postoperative complications include bleeding, anastomotic leak, pancreatic fistula, and intestinal obstruction. The anastomotic leak and pancreatic fistula often resolve with drainage, intravenous antibiotics, nasogastric decompression, and parenteral nutrition (TPN).

Significant late complications included cholangitis, anastomotic stricture, intrahepatic calculi, and bowel obstruction.91 Cholangitis without anastomotic stricture or intrahepatic calculi is treated with antibiotics, whereas endoscopic maneuvers or reoperation are used for anastomotic stricture or intrahepatic calculi.

Caroli Disease and Choledochocele

Partial hepatectomy is indicated for the localized type of Caroli disease and liver transplantation is usually needed for diffuse disease.14,15 Endoscopic unroofing of a choledochocele with sphincterotomy of the CBD, or sphincterotomy alone, are considered the preferred treatment for choldedochocele.92,93

Outcomes

From January 2007 to June 2011, we performed laparoscopic correction in 400 patients with CC at the National Hospital of Pediatrics, Hanoi, Vietnam.30 A total of 238 patients underwent laparoscopic cystectomy plus hepaticoduodenostomy, and 162 had cystectomy plus hepaticojejunostomy. The mean operative time for hepaticoduodenostomy was 164.8 ± 51 minutes and 212 ± 61 minutes for hepaticojejunostomy. Conversion to an open operation was required in two patients. Intraoperative complications included bleeding from the right portal vein in one patient and injury to the right hepatic duct in another. Repair was successful in both patients via laparoscopy. Early postoperative complications included biliary fistula in eight patients (2%), with one patient requiring reoperation. Pancreatic fistula developed in four patients (1.1%), but none of these required reoperation.

The mean postoperative hospital stay was 6.4 ± 3 days for hepaticoduodenostomy and 6.7 ± 0.5 days for hepaticojejunostomy. Follow-up from five to 57 months was obtained in 342 patients (85.5%). Five patients had cholangitis (1.5%) in the hepaticoduodenostomy group and one in hepaticojejunostomy group. Gastritis due to bilious reflux was 3.8% in the hepaticoduodenostomy group. Duodenal bleeding from an ulcer occurred in one patient who underwent a hepaticojejunostomy. Two patients required reoperation, one due to an anastomotic stricture and another due to stenosis at the bifurcation of hepatic ducts.

Gallbladder Disease

Over the past 15 years, gallbladder disease has become a very common problem for older children and young adolescents, especially in the U.S. Historically, gallbladder disease has been confined to children with hemolytic cholelithiasis. However, biliary dyskinesia is now the most common reason for laparoscopic cholecystectomy in many centers.94,95

Biliary Dyskinesia

Biliary dyskinesia is now a commonly seen condition in children.94–100 In this disease, there is poor gallbladder contractility and cholesterol crystals are often seen in the bile. This disorder may have a similar pathophysiology to other diseases with increased numbers of mast cells in the gastrointestinal tract, such as eosinophilic gastroenteritis. A significant increase in mucosal mast cells have been noted in the gallbladder mucosa in patients with biliary dyskinesia when compared with patients with stone disease.101,102

These patients often present with a spectrum of symptoms that are found with gallbladder disease (nausea, vomiting, right upper abdominal pain), but they can also have atypical symptoms. In patients with this disorder, an ultrasound is usually normal. Therefore, a radionuclide study with cholecystokinin (CCK) injection or Lipomul is often needed to make this diagnosis.96,103 Patients often complain of pain at the time the CCK is injected. Most surgeons use a gallbladder ejection fraction of less than 35% as an indicator for cholecystectomy in a patient with symptoms.95,98,104,105 However, not all patients with an ejection fraction of less than 35% will have resolution of symptoms. Symptom resolution seems more likely the lower the gallbladder ejection fraction. In one report, unless children had an ejection fraction of less than 15%, there was not predictable relief of symptoms.106 Thus, a careful discussion with the family is needed in these patients to inform them that their symptoms may not completely resolve following cholecystectomy.

Cholelithiasis

Historically, cholelithiasis has been the primary reason for cholecystectomy in children. Also, in the past, most adolescents with cholelithiasis had hemolytic disease, especially sickle cell disease (SCD) or hereditary spherocytosis (HS). Other reasons for the development of cholelithiasis include long-term TPN, dehydration, cystic fibrosis, short bowel syndrome, ileal resection, use of oral contraceptives, and obesity.107–114 Nonhemolytic stones in adults are primarily cholesterol-based. In younger children, many stones have predominantly calcium carbonate.115–117

Classic symptoms for cholelithiasis include right upper abdominal pain following a fatty meal with associated nausea and vomiting. However, many children do not exhibit these classic symptoms and can have atypical symptoms. In younger children especially, the abdominal pain may be vague and poorly localized. Complications of cholelithiasis are increasingly being reported.118–120 For this reason, cholecystectomy is recommended once cholelithiasis is identified. In patients with SCD, sludge has been felt to be an indication for cholecystectomy as well, even if stones are not present.121 In a study of 35 patients with SCD and sludge, 23 (65.7%) proceeded to develop gallstones at some point.122

In evaluating children with gallbladder symptoms from cholelithiasis, rarely is a plain abdominal film helpful. Ultrasound is the usual initial study and has an accuracy approaching 95%.123 In addition, the ultrasound can document involvement of the common and hepatic ducts, gallbladder inflammation, and other abnormalities in the liver and pancreas. Acute cholecystitis is usually diagnosed using a nuclear medicine study. In patients with acute cholecystitis, the radioactive analogs are excreted in the liver, but do not pass into the gallbladder due to obstruction of the cystic duct.

Special Considerations

There are four special considerations when evaluating the child with gallbladder disease. The first is the sickle cell child. Historically, it has been felt that these patients needed preoperative transfusion.124–128 Many centers still require a hemoglobin greater than 10 mg/dl. However, some centers now stress the importance of adequate hydration in these patients rather than transfusion.

The second circumstance arises in the patient with HS who is undergoing splenectomy. In such patients, an ultrasound should be performed as it is relatively straightforward to remove the gallbladder at the same time if gallstones are noted. In a study of 17 patients with spherocytosis, but not cholelithiasis, none of these patients developed cholelithiasis with a mean follow-up of 15 years.129 Thus, it is probably not necessary to prophylactically remove the gallbladder in HS patients undergoing splenectomy.

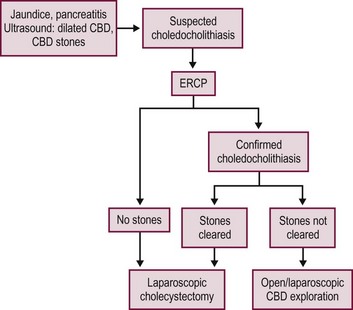

A fourth situation involves the child or adolescent who presents with known or suspected choledocholithiasis. In adults, this situation is usually handled by ERCP with sphincterotomy and stone extraction either before or after the laparoscopic cholecystectomy. ERCP with sphincterotomy has become a routine aspect of adult care and is almost always successful in removing the stone(s). However, in children, many pediatric gastroenterologists are not trained in this technique and many children’s hospitals require the help of an adult endoscopist. Thus, the best approach in children depends on the institutional resources.

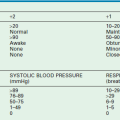

One approach in children with suspected CBD stones is to perform the ERCP and sphincterotomy before performing the laparoscopic cholecystectomy (Fig. 44-9).130–133 If successful, then the surgeon can proceed with the laparoscopic cholecystectomy soon thereafter. However, if the ERCP and sphincterotomy are not successful, the surgeon will know at the time of the laparoscopic cholecystectomy whether or not choledochal exploration is needed. This can be performed laparoscopically for experienced surgeons and with an open approach for those who are not as experienced.

FIGURE 44-9 This algorithm shows one approach for managing children with suspected choledocholithiasis. With this approach, an ERCP is performed prior to the laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a child with suspected choledocholithiasis. If stones are identified and the ERCP and sphinterotomy are successful, then the surgeon can proceed with the laparoscopic cholecystectomy soon thereafter. However, if the ERCP and sphinterotomy are not successful, the surgeon will know at the time of the laparoscopic cholecystectomy whether or not choledochal exploration is needed.

Surgical Techniques

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

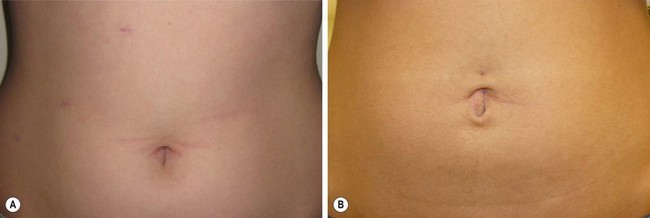

The revolution in minimally invasive surgery began with the laparoscopic approach for cholecystectomy.134–137 Recently, the four-port technique has been modified to a single incision approach through the umbilicus. Currently, there is no objective evidence that the single incision approach has advantages over the four-port technique. The most obvious presumed advantage is cosmesis. However, the small incisions utilized for the four-port technique heal very nicely and the cosmetic benefit appears marginal if there is a benefit at all. Only through prospective randomized trials with patient satisfaction surveys will this cosmetic benefit be determined.

Four-Port Technique

Four small incisions are generally used for the traditional laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A 10 mm port is introduced in the umbilicus and a 10 mm telescope is introduced. (Although the optics are satisfactory with a 5 mm telescope, it is helpful to have a 10 mm port in the umbilicus to extract the gallbladder, especially if it is inflamed, so there is no real benefit to using a 5 mm umbilical port and telescope.) A 5 mm cannula is inserted in the epigastrium to the patient’s right of the midline which becomes the main operating site for the surgeon. Two instruments are then placed on the patient’s right side, one in the right mid-abdomen and one in the right lower abdomen (Fig. 44-10). A stab incision technique is often possible for these two right lateral instruments as they are not exchanged during the operation. Also, 3 mm instruments can be utilized in younger patients at these two sites as well.

FIGURE 44-10 The traditional laparoscopic cholecystectomy technique utilizes four ports. The umbilical cannula is 10 mm (as seen here) or 5 mm depending on the size of the telescope. A 5 mm cannula is inserted in the epigastrium which becomes the main operating site for the surgeon. Two instruments can often be placed through stab incisions on the patient’s right side, one in the mid-abdomen and one in the lower abdomen. These two lateral instruments are not exchanged during the operation so the stab incision technique often works well. Also, in small patients, as depicted in this photograph, 3 mm instruments can be used on the patient’s right side.

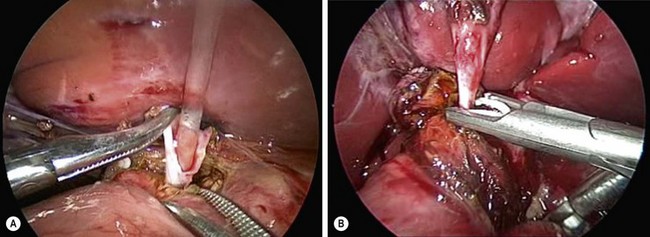

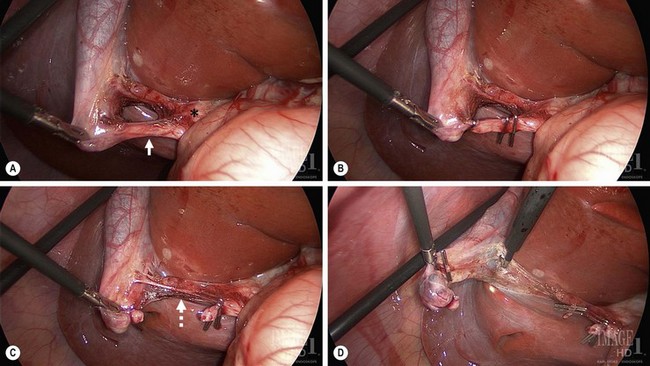

Initial attention is directed towards lysing adhesions to the infundibulum. Dissection follows to identify the cystic duct and cystic artery. At this point, lateral retraction of the infundibulum is essential to orient the cystic duct at 90° to the CBD to help prevent misidentification of these two structures. It is important to visualize the critical view of safety to correctly identify the anatomy. This initial view is bounded by the CBD medially, the cystic duct inferiorly, the gallbladder laterally, and the liver superiorly (Fig. 44-11A).138 After the cystic duct and common duct have been correctly identified, two options exist. A cholangiogram can be performed if the anatomy is unclear or if there is suspicion of common duct stones. If the anatomy is clear and there is no suspicion of choledocholithiasis, then it is appropriate to ligate the cystic duct with endoscopic clips and then divide it (Fig. 44-11B). Similarly, the cystic artery is ligated and divided (Fig. 44-11C). Once these two structures have been ligated and divided, the gallbladder is then detached from the liver using retrograde dissection with cautery (Fig. 44-11D). Either the hook cautery, spatula cautery, or Maryland dissecting instrument connected to cautery can be used for this purpose. Prior to complete detachment of the gallbladder from the liver, the area of dissection should be inspected to ensure hemostasis, and then the gallbladder is completely detached. If there is little to no inflammation, the gallbladder can usually be exteriorized through the umbilical incision without using an endoscopic bag. However, for inflamed gallbladders, it is best to remove the specimen using a bag.

FIGURE 44-11 These four figures depict the salient points for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. (A) The gallbladder infundibulum is retracted laterally to orient the cystic duct (solid arrow) in relationship to the common duct (asterisk). Note the critical view of safety is identified. In this view, the liver is seen through the opened space bounded by the cystic duct inferiorly, gallbladder laterally and the liver superiorly. (B) The cystic duct has been ligated with endoscopic clips. Two clips are placed on the medial aspect of the duct which will remain following duct division. (C) The cystic duct has been divided and the cystic artery (dotted arrow) is visualized. (D) Following ligation and division of the cystic artery, the gallbladder is being dissected away from its liver bed using the hook cautery.

Single-Site Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

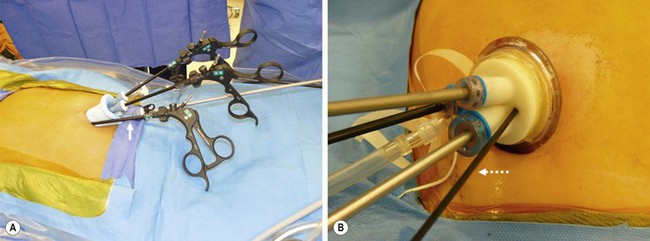

For single site umbilical laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SSULS), it is necessary to use an umbilical incision of approximately 2 cm in length. In the U.S., a pre-manufactured port is often utilized. The two main devices used are the SILS Port (Covidien, Norwalk CT) or the TriPort (Olympus America, Center Valley PA). The SILS Port is a foam port with three working channels. The fourth instrument can usually be placed along the left side of the port (Fig. 44-12A). Although the TriPort is designed for three instruments, a fourth 3 mm instrument can often be inserted through one of the insufflation channels (Fig. 44-12B). It is helpful to have a long telescope so that the telescope holder is standing out of the way of the operating surgeon.

FIGURE 44-12 In the United States, a pre-manufactured port is often utilized for a single site umbilical laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The two main devices used are the SILS Port (Covidien, Norwalk CT) seen on the left and the TriPort (Olympus America, Center Valley PA) on the right. In (A) there are three working channels in this SILS Port. A fourth instrument (solid arrow) can be inserted along the left side of the port. (B) The TriPort is designed for three instruments. However, a fourth 3 mm instrument (dotted arrow) can be inserted through one of the two insufflation channels.

Outside the U.S., many surgeons place a single port in the umbilicus with instruments inserted through the fascia surrounding the umbilicus. Sometimes, low profile, 5 mm individual ports are utilized. Regardless of the technique and orientation of the instruments through the umbilicus, the principles of the procedure are the same as for the traditional four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Lateral retraction of the infundibulum is important for visualization of the triangle of Calot and critical view of safety. The cystic duct and cystic artery are similarly ligated and divided as with the 4-port technique. One difference between the two approaches is that it is best to irrigate and suction all the fluid prior to exteriorizing the gallbladder as gallbladder removal entails removing the pre-manufactured port (if utilized). It can often be difficult to reinsert these ports so it is important to irrigate and suction prior to extracting the gallbladder. After removing the gallbladder and umbilical port, the umbilical fascia is closed with either interrupted or continuous 0-absorbable suture. The skin is approximated with interrupted 5-0 plain sutures.

Children’s Mercy Hospital Experience

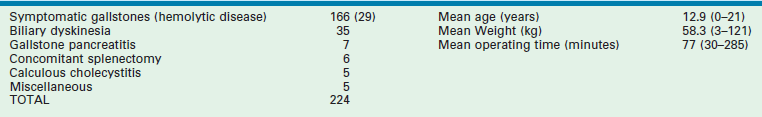

There are surprising few reports in the literature describing laparoscopic cholecystectomy in more than 100 children.94,105,118,120,134 Our group at Children’s Mercy Hospital (CMH) reported a six year experience between September 2000 and June 2006 with 224 patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy (Table 44-2).98 In this study, the mean age was 12.9 years and the mean weight was 58.3 kg. Symptomatic gallstones were found in 166 children and biliary dyskinesia was diagnosed in 35 children. Seven patients presented with gallstone pancreatitis and five had calculous cholecystitis. Six patients required splenectomy and were found to have gallstones. Only 29 patients had hemolytic disease with 18 patients having SCD and 11 having HS. The mean operating time was 77 minutes which excluded patients undergoing a concomitant splenectomy.

TABLE 44-2

Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy at Children’s Mercy Hospital (September 2000–June 2006)

From St. Peter SD, Keckler SJ, Nair A, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the pediatric population. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2008;18:127–30.

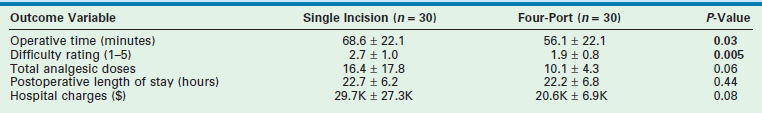

Recently, our group at CMH completed a prospective randomized trial comparing SSULS cholecystectomy and four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy.139 The primary outcome variable was operative time which was based on our own operative times for SSULS cholecystectomy and four-port cholecystectomy. Using an alpha of 0.05 and power of 0.80, 60 patients were enrolled in the study. Patients with signs of inflammation, complicated disease, or weight over 100 kg were excluded. Also, surgeons participating in this study were asked to rate the degree of technical difficult from 1 (easy) to 5 (difficult). There were no differences in patient characteristics preoperatively.

Regarding the outcome data (Table 44-3), the operative time and degree of difficulty as determined by the surgeon were statistically significantly greater for the single incision approach. There were more doses of analgesics and greater hospital charges in the SSULS group which trended toward significance. The postoperative length of hospitalization was not clinically or statistically different between the two approaches. At present, cosmesis appears to be the sole advantage for the SSULS approach compared with the four-port technique (Fig. 44-13). However, the cosmetic advantage appears marginal, at best.

TABLE 44-3

Outcome Data Between Patients Randomized to Single Incision or Four-Port Laparoscopic Cholecystecomy

From Ostlie DJ, Adibe OO, Juang D, et al. Single incision versus 4-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A propsective randomized trial. J Pediatr Surg 2013;48(1):209–14.

FIGURE 44-13 These two patients both underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. (A) The patient underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy using four ports. (B) The patient underwent a single site umbilical laparoscopic cholecystecotmy. To date, the main advantage of the SSULS approach appears to be cosmesis, but this advantage is marginal in most patients.

References

1. Hernanz-Schulman, M, Ambrosino, MM, Freeman, PC, et al. Common bile duct in children: Sonographic dimensions. Radiology. 1995; 195:193–195.

2. Witcombe, JB, Cremin, BJ. The width of the common bile duct in childhood. Pediatr Radiol. 1978; 7:147–149.

3. Kim, HJ, Kim, MH, Lee, SK, et al. Normal structure, variations, and anomalies of the pancreaticobiliary ducts of Koreans: A nationwide cooperative prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002; 55:889–896.

4. Alonso-Lej, F, Rever, WB, Pessagno, DJ. Congenital choledochal cyst, with a report of two cases, and analysis of 94 cases. Surg Gynecol Obstel. 1959; 108:1–30.

5. Todani, T, Watanabe, Y, Narusue, M, et al. Congenital bile duct cyst: Classification, operative procedure, and review of 37 cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1977; 134:263–269.

6. Thu, NX, Cung, HB, Liem, NT, et al. Surgical treatment of congenital cystic dilatation of the biliary tract. Acta Chir Scand. 1986; 152:669–674.

7. Liem, TL, Valayer, J. Dilatation congenitale de la voie biliaire principale chez l’enfant. Etude d’une series de 52 cas. La Presse Med. 1994; 23:1565–1568.

8. Miyano, T, Ando, K, Yamataka, A, et al. Congenital biliary dilatation. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2000; 9:187–195.

9. Lilly, JR, Stellin, GP, Karrer, FM. Forme fruste choledochal cyst. Pediatr Surg. 1985; 20:449–451.

10. Myanio, T, Ando, K, Yamataka, A, et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction associated with nondilatation or minimal dilatation of the common bile duct in children: Diagnosis and treatment. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1996; 6:334–337.

11. Shimotakahara, A, Yamataka, A, Kobayashi, H, et al. Forme fruste choledochal cyst: Long-term follow-up with special reference to surgical technique. J Pediatr Surg. 2003; 38:1833–1836.

12. Thomas, S, Sen, S, Zachariah, N, et al. Choledochal cyst sans cyst-experience with six ‘forme fruste’ cases. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002; 18:247–251.

13. Caroli, J, Soupault, R, Kossakowski, J, et al. La dilatation polykystique congénitale des voies biliaires intrahépatiques: Essai de classification. Sem Hop Paris. 1958; 34:128–135.

14. Madjov, R, Chervenkov, P, Madjova, V, et al. Caroli’s disease. Report of 5 cases and review of literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005; 52:606–609.

15. Kassahun, WT, Kahn, T, Wittekind, C, et al. Caroli’s disease: Liver resection and liver transplantation. Experience in 33 patients. Surgery. 2005; 138:888–889.

16. Davenport, M, Stringer, MD, Howard, ER. Biliary amylase and congenital choledochal dilatation. J Pediatr Surg. 1995; 30:474–477.

17. Shimotake, T, Iwai, N, Yanagihara, J, et al. Innervation patterns in congenital biliary dilatation. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1995; 5:265–270.

18. Imazu, M, Ono, S, Kimura, O, et al. Histological investigations into the difference between cystic and fusiform types of congenital biliary dilatation. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2003; 13:16–20.

19. Babbitt, DP. Congenital choledochal cysts: New etiological concept based on anomalous relationships of the common bile duct and pancreatic bulb. Ann Radiol. 1969; 12:231–240.

20. Jeong, IH, Jung, YS, Kim, H, et al. Amylase level in extrahepatic bile duct in adult patients with choledochal cyst plus anomalous pancreatico-biliary ductal union. World J Gastroenterol. 2005; 11:1965–1970.

21. Ochiai, K, Kaneko, K, Kitagawa, M, et al. Activated pancreatic enzyme and pancreatic stone protein (PSP/reg) in bile of patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction/choledochal cyst. Dig Dis Sci. 2004; 49:1953–1956.

22. Jung, SM, Seo, JM, Lee, SK. The relationship between biliary amylase and the clinical features of choledochal cysts in pediatric patients. World J Surg. 2012; 36:2098–2101.

23. Yamashiro, Y, Miyano, T, Suruga, K, et al. Experimental study of the pathogenesis of choledochal cyst and pancreatitis, with special reference to the role of bile acids and pancreatic enzymes in the anomalous choledocho-pancreatico ductal junction. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1984; 3:721–727.

24. Komi, N, Tamura, T, Miyoshi, Y, et al. Nationwide survey of cases of choledochal cyst. Analysis of coexistent anomalies, complications and surgical treatment in 645 cases. Surg Gastroenterol. 1984; 3:69–73.

25. Spitz, L. Experimental production of cystic dilatation of the common bile duct in neonatal lambs. J Pediatr Surg. 1977; 12:39–42.

26. Davenport, M, Basu, R. Under pressure: Choledochal malformation manometry. J Pediatr Surg. 2005; 40:331–335.

27. Kimura, K, Ohoto, M, Ono, T, et al. Congenital cystic dilatation of the common bile duct : Relationship to anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union. Am J Reoengenol. 1977; 128:571–577.

28. Ono, J, Sakoda, K, Akita, H. Surgical aspect of cystic dilatation of the bile duct. An anomalous junction of the pancreaticobiliary tract in adults. Ann Surg. 1982; 195:203–208.

29. Guelrud, M, Morera, C, Rodriguez, M, et al. Normal and anomalous pancreaticobiliary union in children and adolescents. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999; 50:189–193.

30. Liem, NT, Hien, PD, Son, TN, et al. Early and intermediate outcomes of laparoscopic surgery for choledochal cyst with 400 patients. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012; 22:599–603.

31. Lai, HS, Duh, YC, Chen, WJ, et al. Manifestations and surgical treatment of choledochal cyst in different age group patients. J Formos Med Assoc. 1997; 96:242–246.

32. Shukri, N, Hasegawa, T, Wasa, M, et al. Characteristics of infantile cases of congenital dilatation of the bile duct. J Pediatr Surg. 1998; 33:1794–1797.

33. Okada, A, Nakmura, R, Higaki, J, et al. Congenital dilatation of the bile duct in 100 instances and its relationship with anomalous junction. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1991; 172:291–298.

34. Ando, K, Miyano, T, Kohno, S, et al. Spontaneous perforation of choledochal cyst: A study of 13 cases. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1998; 8:23–25.

35. Ahmed, I, Sharma, A, Gupta, A, et al. Management of rupture of choledochal cyst. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2011; 30:94–96.

36. Voyles, CR, Smadja, C, Shands, WC, et al. Carcinoma in choledochal cysts. Age-related incidence. Arch Surg. 1983; 118:986–988.

37. Imazu, M, Iwai, N, Tokiwa, K, et al. Factors of biliary carcinogenesis in choledochal cysts. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2001; 11:24–27.

38. Kimura, K, Ohto, M, Saisho, H, et al. Association of gallbladder carcinoma and anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union. Gastroenterology. 1985; 89:1258–1265.

39. Todani, T, Watanabe, Y, Toki, A, et al. Carcinoma related to choledochal cysts with internal drainage operation. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1987; 164:61–64.

40. Jang, JY, Yoon, CH, Kim, KM. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in pancreatic and biliary tract disease in Korean children. World J Gastroenterol. 2010; 16:490–495.

41. Otto, AK, Neal, MD, Slivka, AN, et al. An appraisal of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for pancreaticobiliary disease in children: Our institutional experience in 231 cases. Surg Endosc. 2011; 25:2536–2540.

42. Park, DH, Kim, MH, Lee, SK, et al. Can MRCP replace the diagnostic role of ERCP for patients with choledochal cysts? Gastrointest Endosc. 2005; 62:360–366.

43. Huang, CT, Lee, HC, Chen, WT, et al. Usefulness of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in pancreatobiliary abnormalities in pediatric patients. Pediatr Neonatol. 2011; 52:332–336.

44. Irie, H, Honda, H, Jimi, M, et al. Value of MR cholangiopancreatography in evaluating choledochal cysts. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998; 171:1381–1385.

45. Saing, H, Tam, PKH, Lee, JMH, et al. Surgical management of choledochal cysts: A review of 60 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1985; 20:443–448.

46. Shi, LB, Peng, SY, Meng, XK, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of congenital choledochal cyst: 20 years’ experience in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2011; 7:732–747.

47. Fu, M, Wang, YX, Zhang, JZ. Evolution in the treatment of choledochal cyst. J Pediatr Surg. 2000; 335:1344–1347.

48. Watanabe, Y, Toki, A, Todani, T. Bile duct cancer developed after cyst excision for choledochal cyst. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1999; 6:207–212.

49. Kobayashi, S, Asano, T, Yamasaki, M, et al. Risk of bile duct carcinogenesis after excision of extrahepatic bile ducts in pancreaticobiliary maljunction. Surgery. 1999; 126:939–944.

50. Koshinaga, T, Hoshino, M, Inoue, M, et al. Pancreatitis complicated with dilated choledochal remnant after congenital cyst excision. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005; 21:936–938.

51. Lee, SC, Kim, HY, Jung, SE, et al. Is excision of a choledochal cyst in the neonatal period necessary? J Pediatr Surg. 2006; 41:1984–1986.

52. Burnweit, CA, Birken, GA, Heiss, K. The management of choledochal cysts in the newborn. Pediatr Surg Int. 1996; 11:130–133.

53. Howell, CG, Templeton, JM, Weiner, S, et al. Antenatal diagnosis and early surgery for choledochal cysts. J Pediatr Surg. 1983; 18:387–393.

54. Ohi, R, Yaota, S, Kamiyama, T, et al. Surgical treatment of congenital dilatation of the bile duct with special reference to late complications after total cyst excision operation. J Pediatr Surg. 1990; 25:613–617.

55. Miyano, T, Yamataka, A, Kato, Y, et al. Hepaticoenterostomy after excision of choledochal cyst in children: A 30-year experience with 180 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1996; 31:1417–1421.

56. Edil, BH, Cameron, JL, Reddy, S, et al. Choledochal cyst disease in children and adults: A 30-year single-institution experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2008; 206:1000–1005.

57. She, W, Chung, HY, Lan, LCL, et al. Management of choledochal cyst: 30 years of experience and results in a single center. J Pediatr Surg. 2009; 44:2307–2311.

58. Stringer, MD. Wide hilar hepaticojejunostomy: The optimum method of reconstruction after choledochal cyst excision. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007; 23:529–532.

59. Ono, S, Fumino, S, Shimadera, S, et al. Long-term outcomes after hepaticojejunostomy for choledochal cyst: A 10–27 year follow-up. J Pediatr Surg. 2010; 45:376–378.

60. Todani, T, Watanabe, Y, Mizuguchi, T, et al. Hepaticoduodenostomy at the hepatic hilum after excision of choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1981; 142:584–587.

61. Oweida, SW, Ricketts, RR. Hepatico-jejuno-duodenostomy reconstruction following excision of choledochal cysts in children. Am Surg. 1989; 55:2–6.

62. Cosentino, CM, Luck, SR, Raffensperger, JG, et al. Choledochal duct cyst resection with physiologic reconstruction. Surgery. 1992; 112:740–747.

63. Santore, MT, Behar, BJ, Blinman, TA, et al. Hepaticoduodenostomy vs. hepaticojejunostomy for reconstruction after resection of choledochal cyst. J Pediatr Surg. 2011; 46:209–213.

64. Mukhopadhyay, B, Shukla, RM, Mukhopadhyay, M, et al. Choledochal cyst: A review of 79 cases and the role of hepaticodochoduodenostomy. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2011; 16:54–57.

65. Bismuth, H, Franco, D, Corlette, MB, et al. Long term results of Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978; 146:161–167.

66. Martino, A, Noviello, C, Cobellis, G, et al. Delayed upper gastrointestinal bleeding after laparoscopic treatment of form fruste choledochal cyst. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009; 19:457–459.

67. Malhotra, RS, Jain, A, Prabhu, RY, et al. Ischemic stricture of Roux-en-Y intestinal loop and recurrent cholangitis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2005; 24:76–77.

68. Houben, CH, Chan, M, Cheung, G, et al. A hepaticojejunostomy: Technical errors with ‘twists and turns’. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006; 22:841–844.

69. Shimotakahara, A, Yamataka, A, Yanai, T, et al. Roux-en Y hepaticojejunostomy or hepaticoduodenostomy for biliary reconstruction during the surgical treatment of choledochal cyst: Which is better. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005; 21:5–7.

70. Takada, K, Hamada, Y, Watanabe, K, et al. Duodenalgastric reflux following biliary reconstruction after excision of choledochal cyst. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005; 21:1–4.

71. Farello, GA, Cerofolini, A, Rebonato, M, et al. Congenital choledochal cyst: Video-guided laparoscopic treatment. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1995; 5:354–358.

72. Tanaka, M, Shimizu, S, Mizumoto, K, et al. Laparoscopically assisted resection of choledochal cyst and Roux-en-Y reconstruction. Surg Endosc. 2001; 15:545–552.

73. Tan, HL, Shankar, KR, Ford, WD. Laparoscopic resection of type I choledochal cyst. Surg Endosc. 2003; 17:1495.

74. Li, L, Feng, W, Jing-Bo, F, et al. Laparoscopic-assisted total cyst excision of choledochal cyst and Roux-en Y hepatoenterostomy. J Pediatr Surg. 2004; 39:1663–1666.

75. Lee, H, Hirose, S, Bratton, B, et al. Initial experience with complex laparoscopic biliary surgery in children: Biliary atresia and choledochal cyst. J Pediatr Surg. 2004; 39:804–807.

76. Jang, JY, Kim, SW, Han, HS, et al. Totally laparoscopic management of choledochal cyst using a four-hole method. Surg Endosc. 2006; 20:1762–1765.

77. Laje, P, Questa, H, Bailez, M. Laparoscopic leak-free technique for the treatment of choledochal cyst. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007; 17:519–521.

78. Aspelund, G, Ling, SC, Ng, V, et al. A role for laparoscopic approach in the treatment of biliary atresia and choledochal cysts. J Pediatr Surg. 2007; 42:869–873.

79. Hong, L, Wu, Y, Yan, Z, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for choledochal cyst in children: A case review of 31 patients. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2008; 18:67–71.

80. Liem, NT, Dung, LA, Son, TN. Laparoscopic complete cyst excision and hepaticoduodenostomy for choledochal cyst: Early results in 74 cases. J Laparoendos Adv Surg Tech. 2009; 19:s87–s90.

81. Liem, NT, Hien, PD, Dung, LA, et al. Laparoscopic repair for choledochal cyst: Lessons learned from 190 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2010; 45:540–544.

82. Chokshi, NK, Guner, YS, Aranda, A, et al. Laparoscopic choledochal cyst excision: Lessons learned in our experience. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009; 19:87–91.

83. Lee, KH, Tam, YH, Yeung, CK, et al. Laparoscopic excision of choledochal cyst in children: An intermediate-term report. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009; 25:355–360.

84. Kirschner, HJ, Szavay, PO, Schaefer, JF, et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy in children with long common pancreaticobiliary channel: Surgical technique and functional outcome. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010; 20:L485–L488.

85. Diao, M, Li, L, Zhang, JS, et al. Laparoscopic-assisted clearance of protein plugs in the common channel in children with choledochal cysts. J Pediatr Surg. 2010; 45:2099–2102.

86. Miyano, G, Koga, H, Shimotakahara, A, et al. Intralaparoscopic endoscopy: Its value during laparoscopic repair of choledochal cyst. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011; 27:463–466.

87. Woo, R, Le, D, Albanese, CT, Kim, SS. Robot-assisted laparoscopic resection of a type I choledochal cyst in a child. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2006; 16:179–183.

88. Meehan, JJ, Elliots, S, Sandler, A. The robotic approach to complex hepatobiliary anomalies in children: Preliminary report. J Pediatr Surg. 2007; 42:2110–2114.

89. Liem, NT, Pham, HD, Vu, HM. Is the laparoscopic operation as safe as open operation for choledochal cyst in children? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011; 21:367–370.

90. Diao, M, Li, L, Cheng, W. Laparoscopic versus open Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy for children with choledochal cysts: Intermediate-term follow-up results. Surg Endosc. 2011; 25:1567–1573.

91. Yamataka, A, Ohshiro, K, Okada, Y, et al. Complications after cyst excision with hepaticoenterostomy for choledochal cysts and their surgical management in children versus adults. J Pediatr Surg. 1997; 32:1097–1102.

92. Martin, RF, Biber, BP, Bosco, JJ, et al. Symptomatic choledochoceles in adults. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography recognition and management. Arch Surg. 1992; 127:536–538.

93. Dohmoto, M, Kamiya, T, Hünerbein, M, et al. Endoscopic treatment of a choledochocele in a 2-year-old child. Surg Endosc. 1996; 10:1016–1018.

94. Hofeldt, M, Richmond, B, Huffman, K, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for treatment of biliary dyskinesia is safe and effective in the pediatric population. Am Surg. 2008; 74:1069–1072.

95. Siddiqui, S, Newbrough, S, Alterman, D, et al. Efficacy of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the pediatric population. J Pediatr Surg. 2008; 43:109–113.

96. Vegunta, RK, Raso, M, Pollock, J, et al. Biliary dyskinesia: The most common indication for cholecystectomy in children. Surgery. 2005; 138:726–733.

97. Cay, A, Imamoglu, M, Kosucu, P, et al. Gallbladder dyskinesia: A cause of chronic abdominal pain in children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2003; 13:302–306.

98. St. Peter, SD, Keckler, SJ, Nair, A, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the pediatric population. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008; 18:127–130.

99. Halata, MS, Berezin, SH. Biliary dyskinesia in the pediatric patient. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008; 10:332–338.

100. Campbell, BT, Narasimhan, NP, Golladay, ES, et al. Biliary dyskinesia: A potentially unrecognized cause of abdominal pain in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004; 20:579–581.

101. Rau, B, Friesen, CA, Daniel, JF, et al. Gallbladder wall inflammatory cells in pediatric patients with biliary dyskinesia and cholelithiasis: A pilot study. J Pediatr Surg. 2006; 41:1545–1548.

102. Friesen, CA, Neilan, N, Daniel, JF, et al. Mast cell activation and clinical outcomes in pediatric cholelithiasis and biliary dyskinesia. BMC Research Notes. 2011; 4:322.

103. Hadigan, C, Fishman, SJ, Connolly, LP, et al. Stimulation with fatty meal (Lipomul) to assess gallbladder emptying in children with chronic acalculous cholecystitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003; 37:178–182.

104. Brugge, WR, Brand, DL, Atkins, HL, et al. Gallbladder dyskinesia in chronic acalculous cholecystitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1986; 31:461–467.

105. Kaye, AJ, Jatia, M, Mattei, P, et al. Use of laparoscopic cholecystectomy for biliary dyskinesia in the child. J Pediatr Surg. 2008; 43:1057–1059.

106. Carney, DE, Kokoska, ER, Grosfeld, JL, et al. Predictors of successful outcome after cholecystectomy for biliary dyskinesia. J Pediatr Surg. 2004; 39:813–816.

107. Roy, CC, Belli, DC. Hepatobiliary complications associated with TPN: An enigma. J Am Coll Nutr. 1985; 4:651–660.

108. El-Shafie, M, Mah, CL. Transient gallbladder distention in sick premature infants: The value of ultrasonography and radionuclide scintigraphy. Pediatr Radiol. 1986; 16:468–471.

109. Manji, N, Bistrian, BR, Mascioli, EA, et al. Gallstone disease in patients with severe short bowel syndrome dependent on parenteral nutrition. J Parent Enter Nutr. 1989; 13:461–464.

110. Quigley, EM, Marsh, MN, Shaffer, JL, et al. Hepatobiliary complications of total parenteral nutrition. Gastroenterology. 1993; 104:286–301.

111. Lindberg, MC. Hepatobiliary complications of oral contraceptives. J Gen Intern Med. 1992; 7:199–209.

112. Shocket, E. Abdominal abscess from gallstones spilled at laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1995; 9:344–347.

113. Stern, RC, Rothstein, FC, Doershuk, CF. Treatment and prognosis of symptomatic gallbladder disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1986; 5:35–40.

114. Kaechele, V, Wabitsch, M, Thiere, D, et al. Prevalence of gallbladder stone disease in obese children and adolescents: Influence of the degree of obesity, sex, and pubertal development. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006; 42:66–70.

115. Stringer, MD, Taylor, DR, Soloway, RD. Gallstone composition: Are children different? J Pediatr. 2003; 142:435–440.

116. Stringer, MD, Soloway, RD, Taylor, DR, et al. Calcium carbonate gallstones in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2007; 42:1677–1682.

117. Sayers, C, Wyatt, J, Soloway, RD, et al. Gallbladder mucin production and calcium carbonate gallstones in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007; 23:219–223.

118. Holcomb, GW, III., Morgan, WM, III., Neblett, WW, III., et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in children: Lessons learned from the first 100 patients. J Pediatr Surg. 1999; 34:1236–1240.

119. Kumar, R, Nguyen, K, Shun, A. Gallstones and common bile duct calculi in infancy and childhood. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000; 70:188–191.

120. Waldhausen, JHT, Graham, DD, Tapper, D. Routine intraoperative cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy minimizes unnecessary endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2001; 36:881–884.

121. Winter, SS, Kinney, TR, Ware, RE. Gallbladder sludge in children with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr. 1994; 125:747–749.

122. Al-Salem, AH, Qaisruddin, S. The significance of biliary sludge in children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Surg Int. 1998; 13:14–16.

123. Cooperberg, PL, Burhenne, HJ. Real-time ultrasonography: Diagnostic treatment of choice in calculous gallbladder disease. N Engl J Med. 1980; 302:1277–1279.

124. Haberkern, CM, Neumayr, LD, Orringer, EP, et al. Cholecystectomy in sickle cell anemia patients: Perioperative outcome of 364 cases from the National Preoperative Transfusion Study. Preoperative Transfusion in Sickle Cell Disease Study Group. Blood. 1997; 89:1533–1542.

125. Wales, PW, Carver, E, Crawford, MW, et al. Acute chest syndrome after abdominal surgery in children with sickle cell disease: Is a laparoscopic approach better? J Pediatr Surg. 2001; 36:718–721.

126. Bhattacharyya, N, Wayne, AS, Kevy, SV, Shamberger, RC. Perioperative management for cholecystectomy in sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Surg. 1993; 28:72–75.

127. Sandoval, C, Stringel, G, Ozkaynak, MF, et al. Perioperative management of children with sickle cell disease undergoing laparoscopic surgery. JSLS. 2002; 6:29–33.

128. Ware, R, Filston, HC, Schultz, WH, et al. Elective cholecystectomy in children with sickle hemoglobinopathies. Ann Surg. 1988; 208:17–22.

129. Sandler, A, Winkel, G, Kimura, K, et al. The role of prophylactic cholecystectomy during splenectomy in children with hereditary spherocytosis. J Pediatr Surg. 1999; 34:1077–1078.

130. Mah, D, Wales, P, Njere, I, et al. Management of suspected common bile duct stones in children: Role of selective intraoperative cholangiogram and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. J Pediatr Surg. 2004; 39:808–812.

131. Newman, KD, Powell, DM, Holcomb, GW, III. The management of choledocholithiasis in children in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Pediatr Surg. 1997; 32:1116–1119.

132. Shah, RS, Blakely, ML, Lobe, TE. The role of laparoscopy in the management of common bile duct obstruction in children. Surg Endosc. 2001; 15:1353–1355.

133. Zargar, SA, Javod, G, Khan, BA, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy in the management of bile duct stones in children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003; 98:586–589.

134. Muhe, E. Die erste cholecystectomy durch das laparoscope. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1986; 369:804–806.

135. Dubois, F, Berthelot, G, Levard, H. Cholecystectomy by coelioscopy (in French). Presse Med. 1989; 18:980–982.

136. Reddick, EJ, Olsen, DO. Laparoscopic laser cholecystectomy. A comparison with mini-lap cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1989; 3:131–133.

137. McKernan, JB. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am Surg. 1991; 57:309–312.

138. Strasberg, SM, Hertl, M, Soper, NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995; 180:101–125.

139. Ostlie, DJ, Adibe, OO, Juang, D, et al. Single incision versus 4-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A propsective randomized trial. J Pediatr Surg. 2013; 48(1):209–214.