Chapter 217 Chlamydophila pneumoniae

Etiology

Chlamydiae are obligate intracellular pathogens that have established a unique niche in host cells. Chlamydiae cause a variety of diseases in animal species at virtually all phylogenic levels. The most significant human pathogens are C. pneumoniae and C. trachomatis (Chapter 218). C. psittaci is the cause of psittacosis, an important zoonosis (Chapter 219).

Pathogenesis

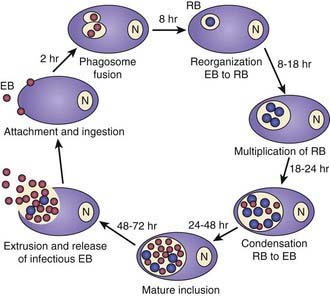

Chlamydiae are characterized by a unique developmental cycle (Fig. 217-1) with morphologically distinct infectious and reproductive forms: the elementary body (EB) and reticulate body (RB). Following infection, the infectious EBs, which are 200-400 µm in diameter, attach to the host cell by a process of electrostatic binding and are taken into the cell by endocytosis that does not depend on the microtubule system. Within the host cell, the EB remains within a membrane-lined phagosome. The phagosome does not fuse with the host cell lysosome. The inclusion membrane is devoid of host cell markers, but lipid markers traffic to the inclusion, which suggests a functional interaction with the Golgi apparatus. The EBs then differentiate into RBs that undergo binary fission. After ~36 hr, the RBs differentiate into EBs. At ~48 hr, release can occur by cytolysis or by a process of exocytosis or extrusion of the whole inclusion, leaving the host cell intact. Chlamydiae can also enter a persistent state after treatment with certain cytokines such as interferon-γ, treatment with antibiotics, or restriction of certain nutrients. While chlamydiae are in the persistent state, metabolic activity is reduced. The ability to cause prolonged, often subclinical, infection is one of the major characteristics of chlamydiae.

Diagnosis

Serologic diagnosis can be accomplished using the microimmunofluorescence (MIF) or the complement fixation (CF) tests. The CF test is genus specific and is also used for diagnosis of lymphogranuloma venereum (Chapter 218.4) and psittacosis (Chapter 219). Its sensitivity in hospitalized patients with C. pneumoniae infection and children is variable. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has proposed modifications in the serologic criteria for diagnosis. Although the MIF test was considered to be the only currently acceptable serologic test, the criteria were made significantly more stringent. Acute infection, using the MIF test, was defined by a 4-fold increase in immunoglobulin G (IgG) titer or an IgM titer of ≥16; use of a single elevated IgG titer was discouraged. An IgG titer of ≥16 was thought to indicate past exposure, but neither elevated IgA titers nor any other serologic marker was thought to be a valid indicator of persistent or chronic infection. Because diagnosis would require paired sera, this would be a retrospective diagnosis. The CDC did not recommend the use of any enzyme-linked immune assay for detection of antibody to C. pneumoniae, because there is concern about the inconsistent correlation of these results with culture results. Studies of C. pneumoniae infection in children with pneumonia and asthma show that >50% of children with culture-documented infection have no detectable MIF antibody.

Block S, Hedrick J, Hammerschlag MR, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae in pediatric community-acquired pneumonia. Comparative efficacy and safety of clarithromycin vs. erythromycin ethylsuccinate. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14:471-477.

Dowell SF, Peeling RW, Boman J, et al. Standardizing Chlamydia pneumoniae assays: recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USA) and the Laboratory Centre for Disease Control (Canada). Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:492-503.

Hammerschlag MR. Intracellular life of chlamydiae. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2002;4:239-248.

Hammerschlag MR. Pneumonia due to Chlamydia pneumoniae in children: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;36:384-390.

Harris J-A, Kolokathis A, Campbell M, et al. Safety and efficacy of azithromycin in the treatment of community acquired pneumonia in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:865-871.

Kumar S, Hammerschlag MR. Acute respiratory infection due to Chlamydia pneumoniae: current status of diagnostic methods. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:568-576.

Rockey DD, Lenart J, Stephens RS. Genome sequencing and our understanding of chlamydiae. Infect Immunol. 2000;68:5473-5479.