3 Children’s Voices

The Experience of Patients and Their Siblings

Life is so strange. Sometimes you feel it’s like a book with chapters to fill, never ending.

Sometimes it’s like a chess game where you have to make each move so carefully.

Other times it’s like a mystery where each hidden chamber reveals its secrets.

It is even a war where to live it is to win it.1 (p. 131)

It’s no privilege having someone with cancer in your family. Of all the things I ever could have chosen, having my brother get cancer is not one of them.2 (p. 38)

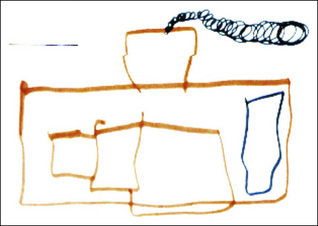

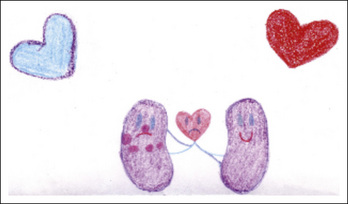

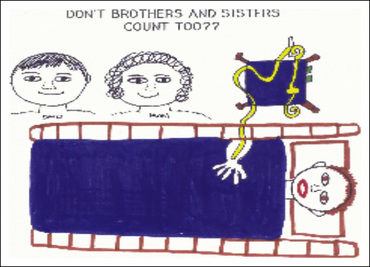

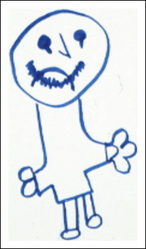

Although the healthy siblings live the illness experience with the same intensity as the patient and parents, historically, they have stood outside the spotlight of attention and care.3–4 Many of these children demonstrate positive growth in their maturity and empathy. Yet their distress can be significant, including elevated rates of anxiety and depression; symptoms of post-traumatic stress; few peer activities; lower cognitive development scores and school difficulties; diminished parental attention and overall ratings of a poor quality of life.5–6 Sibling relationships are a crucial axis within the family system and the children’s mutual caring and devotion can be enhanced rather than overlooked (Figs. 3-1 and 3-2).

Fig. 3-1 Don’t brothers and sisters count too??

(Reprinted from Sourkes B et al. Food, toys, and love: pediatric palliative care, Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 35(9):345–392, 2005.)

Fig. 3-2 I am crying because I want my brother to be with me.

(Reprinted from Sourkes B et al. Food, toys, and love: pediatric palliative care, Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 35(9):345–392, 2005.)

A group of siblings were asked: “Imagine that you are doing a campaign on behalf of siblings of seriously ill children. Draw a poster to illustrate your cause.” The children drew an ill child in a hospital bed, surrounded by medical equipment, the parents at bedside. No siblings are present. They entitled their poster:“Don’t brothers and sisters count too??”7

Developmental Considerations

Infants and toddlers (AGES 0-3)

Preschool children (AGES 3-5)

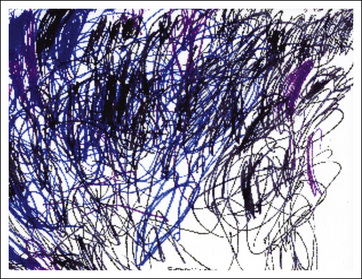

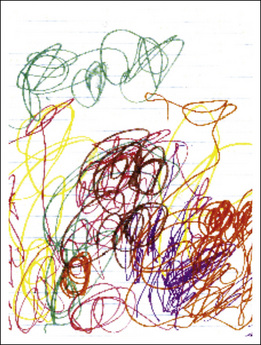

Matthew, 4, who was receiving palliative care for a brain tumor, told the psychologist: “I’m not sick anymore” and adamantly denied any discomfort. His response to most queries by his parents or the medical team was “I’m OK” or “I’m fine” even when it was obvious that he was not. In fact, his non- or underreporting of symptoms made it difficult for his mother to administer pain medication effectively. The psychologist introduced Matthew to a rabbit puppet that he promptly named Donald Bunny. She used the puppet to model the reporting of symptoms (e.g., Donald Bunny has a headache, his eyes hurt when it is too bright, etc.). Matthew watched and listened with some interest. The psychologist left the puppet with him. At the next session, his mother said Matthew had begun reporting symptoms attributed “through the voice” of Donald Bunny. He still would not verbally acknowledge that he had any of these problems; however, his drawing of a dark and threatening “batman tunnel” connoted distress and pain (Fig. 3-3) and contrasted with his earlier bright image (Fig. 3-4). By the next session, while Matthew still would not initially mention any of what had been “bad” during the week, he did allow his mother to list some of his symptoms and would nod affirmatively to them. He then added spontaneously for the first time: “I don’t like when I cough.”8

Fig. 3-3 Batman tunnel.

(Reprinted from Sourkes B: “Psychological impact of life-limiting conditions on the child.” In Goldman, Haines, Liben [eds]. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children (2006). By permission of Oxford University Press.)

Fig. 3-4 Untitled early image.

(Reprinted from Sourkes B: “Psychological impact of life-limiting conditions on the child.” In Goldman, Haines, Liben [eds]. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children (2006). By permission of Oxford University Press.)

A 3-year-old sibling manifested intense anxiety both at home and at preschool during his sister’s long hospitalization. He drew a picture of the hospital with the following commentary: “A building with only three windows because some fell out and broke on the street. People have to be careful or their toes could get cut off. Nobody is in the hospital—they were all in a meeting. But you were there and were happy to see us and then everyone else came back. I was born and I got poison ivy and I died in the car. My sister was scared” (Fig. 3-5).

School-age children (AGES 6-12)

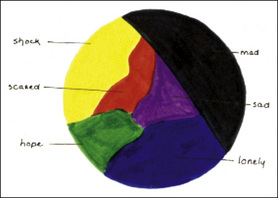

Through a drawing (Fig. 3-6), an 8-year-old boy captured the immediacy of his response to the diagnosis of a life-threatening illness: “When I heard that I had leukemia, I turned pale with shock. That’s why I chose yellow—it’s a pale color. Scared is red—for blood. I was scared of needles, of seeing all the doctors, of what was going to happen to me. I was MAD [black] about a lot of things: staying in the hospital, taking medicines, bone marrows, spinal taps, IVs, being awakened in the middle of the night. I was sad [purple] that I didn’t have my toys and that I was missing out on everything. I chose blue for lonely because I was crying about not being at home and not being able to go outside. Green is for hope: getting better, going home, eating food from home, and seeing my friends.” He has articulated the shock; the fear of everything from the concrete medical procedures to the sudden possibility of an altered future (“what was going to happen to me”); the constellation of sadness, grief, and loneliness of separation; and the absence from his normal life. Accompanying all these feelings is a forthright statement of hope.1(p. 31)

Siblings also experience a sense of “apartness” of being different or stigmatized, by having a seriously ill brother or sister. These children often live in fear of becoming sick themselves, along with suffering a complicated mix of guilt at having escaped the illness and shame at feeling this relief. They are exceedingly conscious of the physical exigencies of the illness, as well as the impact on the child’s functioning. Private theories about what caused the illness are common, and the siblings frequently implicate themselves in the explanation. They often express a fervent wish to understand and be more involved.3–4

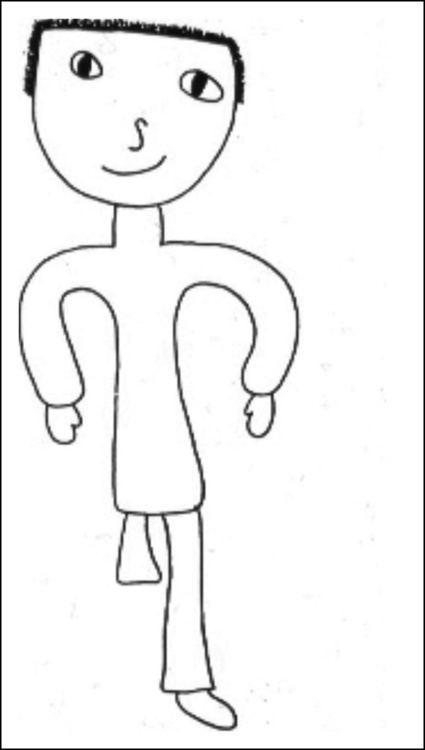

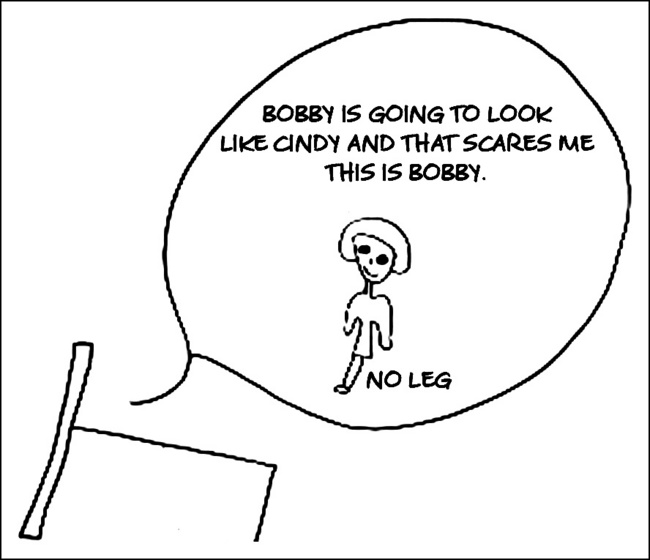

Bobby, 10, reported his version of the sequence of events that led to his sister’s diagnosis of osteosarcoma and amputation: “She hurt her leg on the chain of her bike. She didn’t even notice it until I pointed it out to her. I don’t even ride my bike anymore. One night I went out and broke the chain so I couldn’t ride it. I told my mother it broke by itself, but I broke it.”3 (p. 55) He wrote a story: “This is my sister (drew a one-legged stick figure) and this is me (drew a two-legged stick figure). There is a difference. But I still think that this is the same Cindy and I know that she is not the same to you and I think that she is beautiful.” He then drew a picture of Cindy, stressing her very short hair and her stump. He expressed much concern about how the stump would look.3 (p. 57) (Fig. 3-7) In a subsequent session, Bobby admitted to nightmares of “the same thing” happening to him (Fig. 3-8).

Fig. 3-7 Bobby’s portrait of Cindy.

(Reprinted with permission from Kellerman, J. Psychological Aspects of Childhood Cancer. (1980). Courtesy of Charles C. Thomas, Publisher, Ltd., Springfield, Illinois.)

Fig. 3-8 Bobby’s nightmare.

(Reprinted with permission from Kellerman, J. Psychological Aspects of Childhood Cancer. (1980). Courtesy of Charles C. Thomas, Publisher, Ltd., Springfield, Illinois.)

A ten-year-old sibling spoke about her brother’s diagnosis of a brain tumor: (Fig. 3-9) “I feel scared (green)—I feel as if I don’t really know what is happening. Sad is blue—at first my parents just told me that my brother needed an operation. They didn’t say it was cancer. Confused is yellow—just all mixed feelings—I don’t know what to think. Hopeful is purple—bright—I don’t really have a lot of hope, but maybe just a little. Angry is red because that is a mad color. Why him? What did it have to happen to him? My drawing is called ‘Mixed Messages’ because I have all of these different feelings and everyone is telling me different things. Like they say mostly that he is going to be okay, but they—and I—don’t really believe it….”9

Adolescents (13-18 YEARS)

“You are going to mature very fast right now. You have to make life and death decisions. You have to accept things that children who are young adults between the ages of thirteen and nineteen don’t normally have to face.” It’s like: “Grow up right now and become what you have to become to deal with this.” I never had the chance to be sweet sixteen. I never had the chance to be gay old seventeen. I had to automatically be an adult, and it was very hard.”2

Clinical Themes

The illness experience

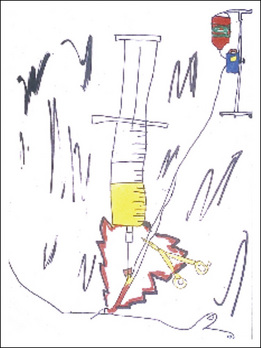

Patient: “PAIN—once I felt as if the IV was exploding in my arm!”

The child went on to describe the excruciating pain he had felt amidst the chaos of his IV pole falling over and crashing7 (p. 365) (Fig. 3-10).

Fig. 3-10 IV exploding in my arm.

(Reprinted from Sourkes B et al. Food, toys, and love: pediatric palliative care, Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 35(9):345–392, 2005.)

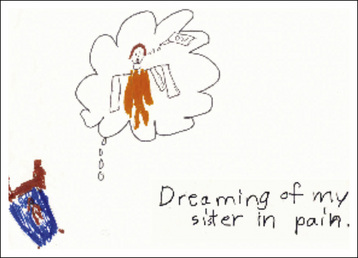

In response to the question: “What is the scariest feeling, thought, or experience you have had since your sister became ill?” a child drew her response: “Dreaming of my sister in pain.” She depicted herself as a diminutive brown figure in a small bed, overwhelmed by the dream image of her sister in bright orange screaming “OW” (Fig. 3-11).

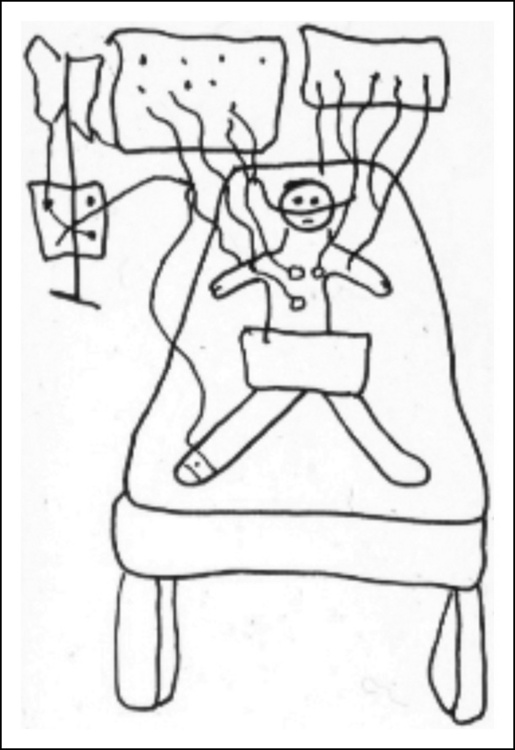

A 12-year-old child with end-stage renal disease depicted his absolute dependence on hemodialysis to live. He entitled his drawing “MY machine.” One hand is literally plugged into the machine while the other is in a “thumbs up” gesture. His facial expression is ambiguous—triumph, horror, or a combination of the two (Fig. 3-12). A sibling’s drawing of his brother hooked up to multiple wires and monitors communicates his fear at what he has witnessed (Fig. 3-13).

Concerns about sexuality can be quite pronounced in children living with serious illness. Sexuality in all its facets represents a life force, which is exactly the struggle in which these children are engaged. Furthermore, the body is the focus of illness and sexuality is an integral part of that same body. Sexual identity, functioning, and fertility—and the potential or actual losses thereof—loom particularly large for adolescents, although younger children may also harbor worries about immediate and long-term effects of illness and treatment.10

An 18-year-old boy who had had his leg amputated expressed fears about his sexual functioning and how his girlfriend would react. On a clinic visit shortly after surgery, he greeted the psychologist: “You’ll be glad to know I still work! I was glad too!”10

A 12-year-old girl insisted on reading the informed consent for her bone marrow transplant. When she asked what “sterility” meant, her physician replied: “It means you can’t have babies.” She retorted quickly and with spirit: “Then I’ll adopt!” However, following this discussion, she spoke frequently about her sadness at the loss of fertility.10

For all the children, their longing to return to their “normal life” or their “life from before” (or, in situations where a child has a congenital condition, “life without sickness”) is counterbalanced by the recognition that the presence of illness in the family cannot be erased, nor its impact reversed.1 Rather, the children are confronted with the extraordinary challenge of pursuing the developmental tasks of childhood and adolescence while negotiating the illness experience.

Awareness of the life-threatening nature of the illness

Children’s awareness is a fluid process not a static state, and depends on factors including: their current medical status and knowledge about the illness (or that of the sibling’s), their “wisdom of the body,” the urgency and intensity of treatment, the emotions of family and caregivers, the family communication style and encounters with other children who are ill.1,11 These issues are particularly poignant when more than one child in the family has the illness. References to death may be somewhat veiled and allusive, or direct and explicit.

During a psychotherapy session in the last few months of her life, 13-year-old Evangeline drew a picture entitled “My Lungs.” She portrayed herself as a heart with a sad face between (and connected to) two lungs: “One of my lungs is sad because it has disease in it; the other lung is smiling because it is still OK” (Fig. 3-14). Her use of the word “still” expressed her qualified confidence in its current state.

A 4-year-old child had always done medical play with a stuffed Curious George monkey, giving him shots and bandages. In a session close to her death, she methodically covered him with tissues and taped them in place. By the end of her play, he appeared to be buried under a shroud. She was very quiet during her activity and made no comment about her play8 (Fig. 3-15).

Fig. 3-15 Curious George under a shroud.

Reprinted from Sourkes B: “Psychological impact of Life-Limiting conditions on the child.” In Goldman, Haines, Liben [eds]. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children (2006). By permission of Oxford University Press.

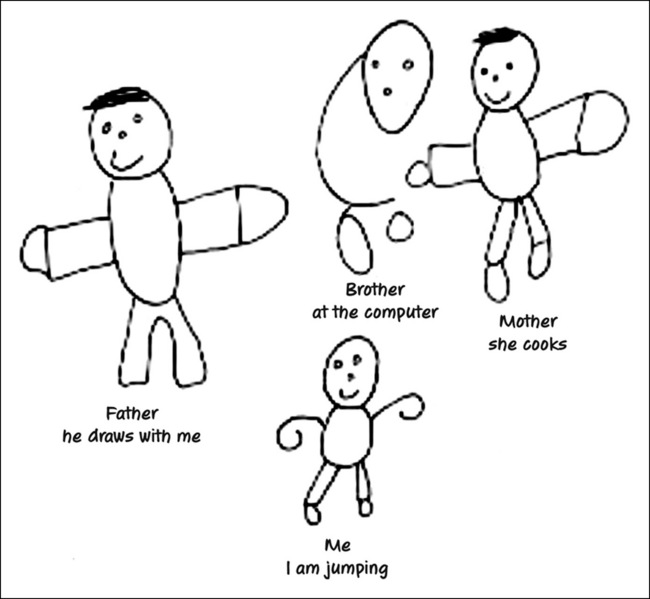

An 8-year-old boy with muscular dystrophy was tripping and falling constantly, but adamantly refused to use a wheelchair, protesting that he did not need it. His older brother with the same disease was already severely compromised. In a family drawing, the child portrayed himself jumping and smiling; he drew his brother as an incomplete almost ghost-like figure at the computer. The extremities of all four family members are distorted or missing. This child’s awareness—and attempted denial—of his own progressive deterioration as well as his brother’s status (and thus his own in the future) are embedded in the drawing (Fig. 3-16).

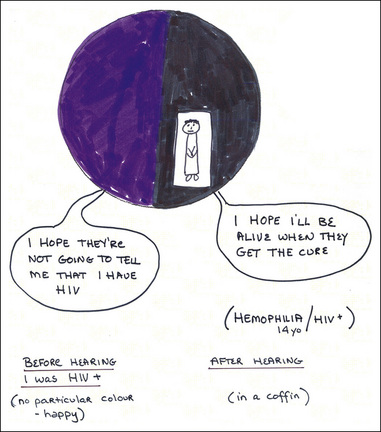

A 14- year-old boy with hemophilia who had just been informed that he was HIV-positive graphically described the experience: “Before hearing the news, I was just thinking: I hope they are not going to tell me I have HIV” (on a “happy” purple background). After hearing the news, he depicted himself in a coffin against a black background saying: “I hope I’ll be alive when they get the cure…” (Fig. 3-17).

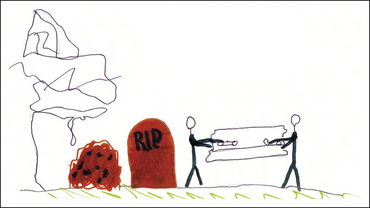

An 8-year-old sibling said his biggest worry was that his brother might die of his illness. He drew a somber picture of two faceless black figures lowering a coffin into the ground, next to a tombstone inscribed “RIP“and a pile of dirt. Anxious scribbling filled part of the page (Fig. 3-18).

Anticipatory grief

Children’s expressions of anticipatory grief—for many cumulative losses—accompany their awareness of the implications of the illness.1–2,12 Patients grieve the loss of control over their body and disease, the loss of identity of what had been their roles and functions in the family and in the outside world, and the foregoing of future goals. The children face the ultimate leave-taking, the departure from all that is familiar and loved. Loss of relationships—expressed through fears of separation, absence, and ultimately death itself—is paramount, and is the dimension shared with the siblings.

An interchange between Mariesa, 16, and Mikaela, her 10-year-old sister with a brain tumor:

Mariesa: “And she knows that I love her no matter what.”13

An adolescent with thalassemia, whose brother had died in infancy of the same disease, drew a cemetery image (Fig. 3-19).

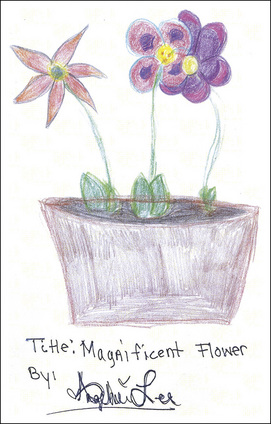

A few weeks before her death, Evangeline, age 13, spontaneously drew a pot of three flowers: two similar blooms nestled into one another, the other flower of a different kind leaning away. She was an only child who worried about how her parents would manage without her after her death (Fig. 3-20). She mused, “What will I call this drawing? ‘Flowers on a Journey’… No… ‘Flowers Forever’… No. I think I will call it ‘Magnificent Flower.’” She moved away from the title that reflected her vulnerability and instead chose the least-threatening option.

A 7-year-old girl had a recurrent dream: “In the dream, I want to be with my mother, and I can never quite get to her.” The girl recounted the dream in a joint psychotherapy session with her mother. Whereas the mother found the dream “excruciating,” her daughter articulated that “even though the dream is very sad, it’s not a nightmare.” The dream eventually provided the focal image for mother and child to work through the anticipatory grief process2 (p. 70).

The distillation of anticipatory grief to its essence marks the imminence of death. At times imperceptibly, at other times dramatically, children often turn inward as they pull back from the external world. Cognitive and emotional horizons narrow because all energy is needed simply for physical survival. A generalized irritability is not uncommon. Children may talk very little, and may even retreat from physical contact. Although such withdrawal is not universal, a certain degree of quietness is almost always in evidence. This behavior is a normal and expected precursor to death.1

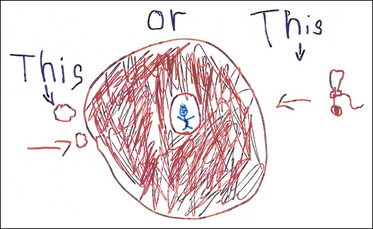

The Voice of the Child in Decision-Making

Mikaela drew a picture entitled “This or This.” (Fig. 3-21) when she found out that her disease had recurred. On one side of a doughnut she depicted tumor cells, on the other side she drew a needle for spinal taps. In the middle of the doughnut is a little stick figure of a person. At the time of drawing the picture, Mikaela said: “I hate needles and spinal taps, but I also don’t want my tumor to come back. If I don’t have all the needles, then more tumor cells will grow. So if I don’t want them to grow, I have to have all those awful needles. That’s why I feel as if I am stuck in the middle of a doughnut.” Reflecting on the drawing months later, Mikaela elaborated more explicitly: “What I mean by ‘I was stuck in a doughnut’ is that I had two choices and I didn’t want to take either of them. One of the choices was to get needles and pokes and all that stuff and make the tumor go away. My other choice was letting my tumor get bigger and bigger and I would just go away up to heaven…. My mom wanted me to get needles and pokes. But I felt like I just had had too much—too much for my body—too much for me…. So I kind of wanted to go up to heaven that time…. But then I thought about how much my whole entire family would miss me and so just then I was kind of like stuck in a doughnut….”7

Fig. 3-21 This or this.

(Reprinted from Sourkes B et al. Food, toys, and love: pediatric palliative care, Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 35(9):345–392, 2005.)

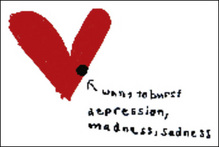

A 10-year-old sibling whose sister was critically ill stated intensely: “I am mad at all the doctors. I think that they are giving up too soon. I KNOW that my sister will not die, I just know it. But I feel like it’s only me who feels that way and no one listens to my opinion.” She then drew a heart called “wants to burst” with a black dot of “depression, madness and sadness” (Fig. 3-22).

Over the last decade, there has been increased recognition of children’s participation in making treatment decisions. Attention to children’s experience of their illness is essential not only to enhance their quality of life, but also as a guide to clinical decisions and goals of care. This may become more challenging as an illness progresses, especially if the family and clinicians are reticent to discuss death with children. A landmark study14 showed that bereaved parents who had talked with their child about death had no regrets about doing so, whereas those who had not engaged in such discussions were often left with regret. While younger children may not be able to take an abstract or time-based perspective, their expressed fears, concerns, and specific preferences can provide the basis for decisions. Older children and adolescents who have more capacity to plan over time can engage in complex end-of-life decisions that may be driven by interpersonal relationships.15–16 However, because actual assessment tools are only in the early stages of development, clinicians are often left to rely on their own judgment to assess children’s understanding of the contingencies they face.

Children are often aware of the diminishing curative or life-prolonging options available. It is at this time that they may ask anxiously: “What if this medicine doesn’t work? What will you give me next?”1 Input from members of the interdisciplinary team can be crucial at this juncture: children often express their understanding, awareness, and thoughts about treatment options and living or dying to individuals other than their parents or primary physician. Frequently, their most candid disclosures evolve within the context of psychotherapy.

The following vignettes illustrate a spectrum of children’s involvement in decision-making.

Child’s voice is instrumental in determining plan:

A 7-year-old girl told her parents that she was too tired to fight anymore, and that she wanted to give up. She added: “If I have to continue suffering, I would rather be in heaven.” She repeated this statement to the medical team. The parents acknowledged that their child’s statements were major determinants in their shifting to a palliative care plan1 (p. 156).

The inadvertent burden of decision-making on a child:

An 11-year-old child had been through many remission-relapse cycles, and had been informed and involved in all aspects of her treatment from the beginning. When she was offered radiation therapy for palliative symptom control, she confided to her psychologist: “I’m scared because I’m not so good at making decisions. My parents want me to have radiation, but a little voice in me tells me not to…. My mother always said that if I die, she wants me to die happy and at home. If I had radiation, I’d have to come into the hospital every day. And I don’t know if radiation will really help, or if I would die anyway.” Despite what had been her clear understanding of the reason for radiation therapy (exclusively for palliative symptom management), her intense emotion and hope overrode her intellectual grasp as she wondered whether the radiation would help her to live longer (“or would I die anyway”)1 (p. 156).

Role of the Mental Health Professions and Child Life

Palliative care clinicians of all disciplines must rely on many sources to understand and relieve children’s distress. The etiology of psychological symptoms in children are multi-factorial, and responsive to a host of physical and situational variables. For younger children, physical complaints and irritable or withdrawn behavior may be the most common expressions of emotional distress. The differential for depression or anxiety syndromes includes delirium and encepha-lopathy, medication side effects, and pain or other physical symptoms such as dyspnea or fatigue. Anxiety may be generalized or specific to separation, procedures, or the anticipation of pain. Medical trauma and terror can also present in a variety of ways in both children and their parents. (See Chapter 26.) Uncertainty around the illness, misconceptions, and lack of communication or secrets surrounding the illness can also fuel distress and changes in behavior. Mental health clinicians, and the entire medical team, need to pay close attention to the history provided by the parents. They also have a specific role, in the course of an evaluation or psychotherapy, to uncover the individual child or adolescent’s perceptions of the illness and its implications.

Because children’s experiences are so intertwined with those of their parents and the professional team, it is essential to clarify whose distress is being reported. There are often discrepancies in parent and child assessment of symptoms of depression, for example, with parents both over- and underreporting as compared with their child’s self-reports.17 Children and adolescents in particular, try to protect their parents from the extent of their distress.18 Clinicians who care for these children must be vigilant about the influence of past personal or professional experiences, especially those involving loss, on their assessment of a particular situation.

Psychological treatment

“I felt much better because I knew that I had somebody to talk to all the time. Every boy needs a psychologist! To see his feelings!”1 (p. 3).

“You don’t look at me like other people do and judge my behavior. Instead you analyze my behavior and try to get to the root of it. Mostly you helped me get to the root of it, and helped me handle it on my own. You can ask for your family’s support, wisdom, experience; but it’s not fair to burden them. I have an older sister whom I talk to, but at the same time, I don’t want to upset her. I don’t want to make her cry for me, I know that when I first met you, I didn’t want to talk about it. I wanted to handle it on my own. But that faded so quickly because you’re so helpless. You really do need somebody that can come in and help you”2 (p. 113).

Ideally, the psychological status of each child receiving palliative care should be evaluated in order to plan for optimal care, in the same way that medical and nursing assessments are carried out. The contribution of child psychology and psychiatry, as well as other mental health disciplines, provides specialized knowledge and skills. The specific and unique interventions include: evaluation of the child’s psychological status, diagnosis of psychological/psychiatric symptoms and disturbance, psychotherapy and psychotropic medication, and consultation to families and the team. The healthy siblings are included within this network of care.8

Reasons for referral for psychological treatment include:

Psychotherapy is the treatment modality unique to the mental health clinician and can add a crucial dimension to a child’s comprehensive care. It facilitates psychological adjustment by providing a protected framework for the expression of profound grief, and for the integration of all that he or she has lived, albeit in an abbreviated lifespan. The child conveys the experience of living with uncertainty and the threat of loss through words, drawings, and play and transforms the essence of his or her reality into expression. Furthermore, even for a young child, considerations about remaining quality of life may be discussed.1,7 Psychotherapy may be the sole intervention, or may be combined with psychotropic medication and behavioral symptom-management techniques.

With the intrusion of the illness, the relationship between children and their parents organizes around the pivot of potential loss. Thus, it is critical that the mental health clinician not intercede as a divisive wedge between them. From the outset, an ongoing alliance diminishes this threat, and optimizes the outcome of the work. Such collaboration is an essential part of the process. Because the parents must sustain the therapeutic work in the child’s day-to-day encounters with both physical and emotional stresses, their role cannot be underestimated.1

The availability of psychological consultation in pediatric palliative care is often limited. While it is true that psychological treatment is not universally necessary, the opportunity to identify “high-risk” children and intervene in a timely fashion is often missed. The challenge, under these circumstances, is to provide thoughtful emotional support for the child in a carefully planned manner. Such support comes in many forms, from a willingness to listen and answer questions, to regular visits at expected times, to creative art and play that allows the child to express feelings and concerns. If a child has demonstrated particular comfort or closeness with one particular individual on the team, that person may be designated as a resource for the child, with efforts to ensure consistent contact between them. On a cautionary note, there are risks when unskilled or inadequately trained personnel attempt to undertake a psychotherapeutic role. These risks include: opening up too much vulnerability in the child and then not knowing how to contain the emotion; interpreting – beyond simply clarifying – the child’s disclosures; promising confidentiality that may set up competition, rather than collaboration, with the parents; and becoming involved with the child beyond appropriate boundaries.8

Child life intervention

Child life specialists play a vital role in reducing the impact of stressful and traumatic events on children in medical settings.20 They work with children and adolescents individually and in groups and develop the programs in the hospital playrooms. They provide both therapeutic intervention and social recreation, framed by their understanding of children’s responses to illness. Their insights are integral to the team’s understanding of a child’s adjustment to the overall experience. They are often a source of emotional support to the siblings and parents as well.

Summary

Portions of (page 23 in this chapter are reprinted with permission from Brandell, J. Countertransference in Psychotherapy with Children and Adolescents. Jason Aronson Publishing Company, 1992. Additional portions of this chapter are reprinted with permission from Sourkes, B. The Deepening Shade: Psychological Aspects of Life-Threatening Illness, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992.

1. Sourkes B. Armfuls of time: the psychological experience of the child with a life-threatening illness. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1995.

2. Sourkes B. The deepening shade: psychological aspects of life-threatening illness. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1982.

3. Sourkes B. Siblings of the pediatric cancer patient. In: Kellerman J., editor. Psychological aspects of childhood cancer. Springfield, Ill: Charles C. Thomas; 1980:47-69.

4. Sourkes B. Siblings of the child with a life-threatening illness. J Child Contemp Soc. 1987;19:159-184.

5. Sharpe D., Rossiter L. Siblings of children with a chronic illness: a meta-analysis, J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27(8):699-710.

6. Alderfer M.A., Long K.A., et al. Psychosocial adjustment of siblings of children with cancer: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 27 Oct 2009. Epub

7. Sourkes B., Frankel L., Brown M., Contro N., et al. Food, toys, and love: pediatric palliative care. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2005;35(9):345-392.

8. Sourkes B. The psychological impact of life-limiting illness. In: Goldman A., Haines R., Liben S., editors. Oxford textbook of pediatric palliative care. London: Oxford University Press, 2006.

9. Wolfe J., Sourkes B. Palliative care for the child with advanced cancer. In: Pizzo P., Poplack D., editors. Principles and practice of pediatric oncology. ed 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2006:1531-1555.

10. Sourkes B. The child with a life-threatening illness. In: Brandell J., editor. Countertransference in child and adolescent psychotherapy. New York: Jason Aronson; 1992:267-284.

11. Bluebond-Langner M., editor. The private worlds of dying children. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978.

12. Sourkes B. The broken heart: anticipatory grief in the child facing death. J Palliat Care. 1996;12(3):56-59.

13. Kuttner L. Making every moment count: pediatric palliative care. Documentary film. National Film Board of Canada, 2003.

14. Kreicbergs U., Valdimarsdóttir U., Onelöv E., Henter J., Steineck G. Talking about death with children who have severe malignant disease. JAMA. 2004;351(12):1175-1186.

15. Hinds P.S., Schum L., Baker J.N., Wolfe J. Key factors affecting dying children and their families. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(Suppl 1):S70-S78.

16. Hinds P.S., Drew D., Oakes L.L., Fouladi M., Spunt S.L., Church C., Furman W.L. End-of-life preferences of pediatric patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9146-9154.

17. DeJong M., Fombonne E. Depression in pediatric cancer: an overview. Psychooncology. 2006;15:553-566.

18. Stuber M.L., Gonzalez S., Benjamin H., et al. Fighting for recovery: group interventions for adolescents with cancer and their parents, J Psychother Pract Res. 1995;4(4):286-296.

19. Sourkes B., Kazak A., Wiener L. Psychotherapeutic interventions. In: Kazak A., Kupst M., Pao M., Patenaude A., Weiner L., editors. Quick reference for pediatric oncology clinicians: the psychiatric and psychological dimensions of pediatric cancer symptom management. Charlottesville, Va: International Psycho-Oncology Society Press, 2009.

20. Munn E., Robison K. Palliative care and the role of child life. Child Life Council. 2004;22(3):4-6.