2 Children’s place in society

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child

A good starting point is to think in terms of children’s rights. The 1990 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) is the document on which the basis of children’s rights, and their place in society, are founded (see www.unhchr.ch). It has been ratified by every country in the world with the exceptions of Somalia and the United States of America.

The UNCRC begins by describing underpinning principles:

• The interests of children are paramount

• Children have the right to be supported in their own families and communities, but are not their families’ ‘property’.

Rights of protection

• Not to be separated from their parents against their will except where to remain with them would harm the child (article 9)

• To special protection such as fostering or adoption when children are deprived of their family environment (article 20).

These rights reiterate the importance of families for the welfare of children.

Parents’ and doctors’ responsibilities and the child’s best interests

Physical punishment of children

• It is technically a form of assault which is illegal where adults are concerned

• It leads to a punitive form of child behaviour management, which is ineffective and potentially harmful

• There is no distinction between physical punishment and physical abuse of children

• It models aggressive responses to children that will influence detrimentally their responses to other people and their own children (‘the cycle of abuse’)

• It is a form of domestic violence

• Countries that have made this illegal have far lower rates of physical child abuse.

Consent

Inequalities in child health

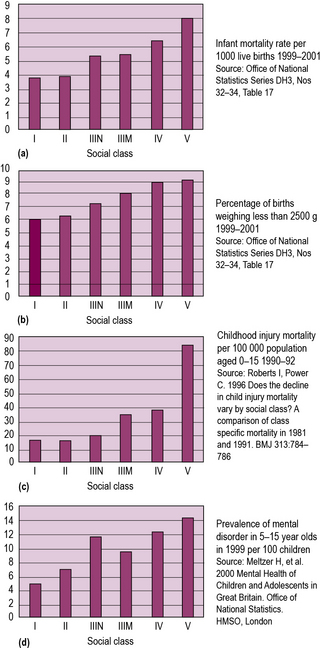

Social inequalities exist in almost all aspects of children’s health. Babies from poorer backgrounds are born smaller, are more likely to die in infancy, and more likely to suffer from infectious diseases. In childhood, accidental injury is strongly associated with social class, as are mental health problems and suboptimal nutrition, with both obesity and poor growth being more prevalent. In young adulthood, teenage pregnancy, mental illness, drug abuse and death from injury and violence all show steep social gradients. Finally, many of the chronic degenerative diseases of old age, such as heart disease, stroke and chronic lung disease, are strongly influenced by adverse social circumstances in childhood (see Figure 2.1).

Marginalized groups of children

Why is this important?

There are several reasons why doctors looking after children need to be aware of these matters.

• Many children seen in clinics or hospital will come from poor, disadvantaged or marginalized families. It is important for doctors to be aware of the social conditions of their patients

• Knowing the effect of social circumstances on children’s health will help us understand the reasons for some of their health problems, and may guide our treatments and advice

• Doctors have a duty to advocate for their patients. Knowledge of the effects of poverty and deprivation will inform the way that we advocate for individual children and their families

• Doctors have a wider duty of public health advocacy. This includes supporting measures to improve equity within society and to draw attention to the health consequences of poverty and discrimination. This is particularly relevant for paediatricians because children are a group who are not in control of their own social circumstances.

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. www.unicef.org/crc/

Child poverty in the UK. Joseph Rowntree Foundation. www.jrf.org.uk

Protecting children and young people: The responsibilities of all doctors. http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/13257.asp.

Millennium Development Goal 4 – Reducing child mortality. www.unicef.org/mdg