Chapter 6 Childhood illness – assessment and management of primary survey negative children

Introduction

This chapter describes the assessment and findings associated with illnesses that commonly affect children. It aims to be a guide to common presentations and treatment rather than a comprehensive review of all paediatric conditions. Chapter 5 describes the identification and initial management of potentially life-threatening problems. Box 6.1 describes the objectives for this chapter.

Secondary survey

A secondary survey will be required for all children who have not required transfer to hospital following the primary survey (see Chapter 5). Its aim is to fully assess the child so that decisions about their future management and disposal can be safely made. The SOAPC system (Box 6.2) can be used to undertake this survey but is modified to take account of the particular needs of children (see Chapter 5).

Subjective assessment

The parents of children with chronic illnesses (such as renal disease) or congenital problems are likely to have considerable expertise about assessment and management of the condition – as indeed may the children themselves. Practitioners should not be dismissive of information provided and suggestions made by ‘expert’ parents and children. It is important to remember, however, that although they be very knowledgeable about their field of expertise, they are likely to know no more than other people about other medical problems.

Objective examination

Before approaching a child directly, it is a good idea to observe their general behaviour (Fig. 6.1). Are they passive or active? Are they playing normally? Do they pay attention to their surroundings?

The content of the physical examination should be similar to that for an adult, although the order in which each system is assessed may be modified depending on the age and behaviour of the child (see Chapter 5). A cardiovascular, respiratory and abdominal examination should be undertaken as appropriate and opportunistically. There are some aspects, however, that are particularly important to the examination of the child.

Temperature

Taking the child’s temperature is of limited value in primary care as the presence or absence of a fever does not confirm or rule out serious disease. There are various confounding problems, such as whether or not the child has received an antipyretic and what part of the body is used to assess temperature. Indeed authorities still debate what the upper limit of normal is. It is, however, recognised that very young babies (for example, less than 6 months old) who have a significant fever (>38.5 °C) or who are hypothermic (<35 °C) are more likely to have serious disease. Young children may sometimes tolerate very high temperatures (>40 °C) with little apparent discomfort or serious pathology. Significant fever can usually be detected, if no thermometer is available, by touching the skin of the child’s trunk.

Analysis (differential diagnosis) and treatment and disposal (plan)

Common presentations

The irritable child

A common presentation that can be difficult to address is a baby who is reported to cry excessively. A truly irritable baby dislikes handling and must be assumed to have serious illness and be admitted urgently to hospital. More common is the baby who will not settle or settles only briefly, or the misery of the febrile toddler: these children can cause considerable concern to new parents and healthcare professionals alike but are not necessarily very ill. The cause may be due to a multitude of reasons from significant pathology to poor parenting skills. Even when the practitioner can confidently determine there is no significant clinical problem (difficult at the best of times) admission to hospital or referral for further support should be considered if parents remain anxious.

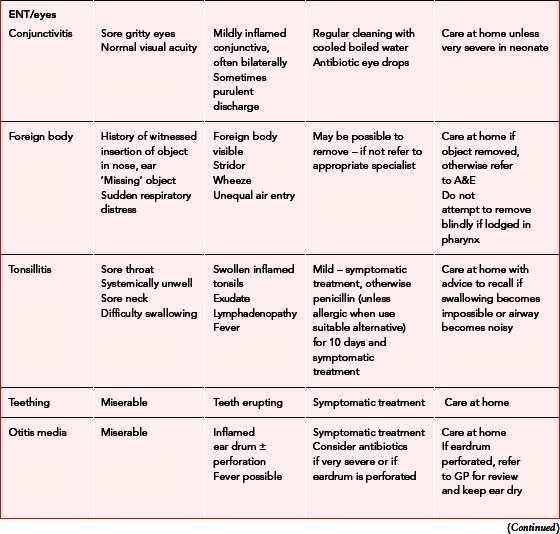

ENT problems

These are common in children. Infants are obligate nasal breathers up to about 6 months of age. Consequently a blocked nose may result in a significant increase in the work of breathing and may produce difficulty feeding. Otitis media, presenting with a red and sometimes bulging or perforated eardrum, is a common finding in a child with earache (see Chapter 11). Antibiotics have not been shown to alter the outcome of the disease in the majority of patients, but are still often given. The SIGN guidelines for management of otitis media recommend that antibiotics should not be immediately prescribed, but suggest a 5-day course of amoxicillin should be made available for collection from the GP if the child’s condition has not improved after 72 hours. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) and ibuprofen (alone or in combination) usually provide effective symptomatic relief.1 Otitis externa is less common and usually also presents as earache (which may be severe), with or without a discharge. Antibiotic/steroid ear drops are appropriate.

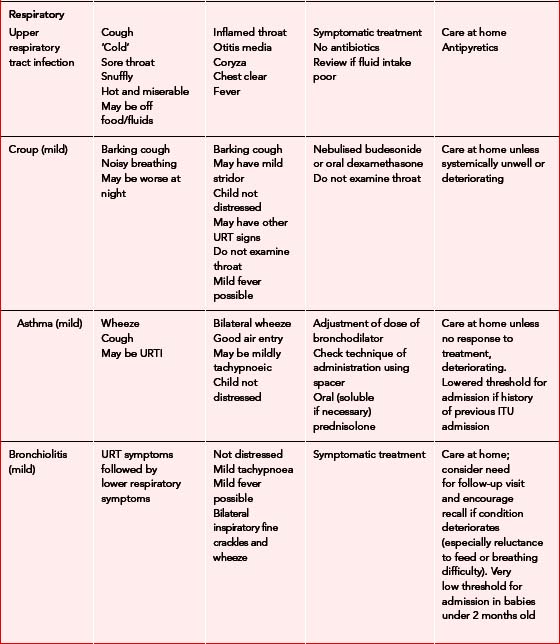

Respiratory problems

Respiratory problems account for approximately 40% of children admitted to hospital, with the majority being for asthma (see Chapter 4). Croup is usually viral and presents with a seal-like bark with or without systemic illness or associated stridor. There may be other symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection including fever but the child is not generally very unwell. Sudden onset, short history, drooling due to pain and a very toxic child support the diagnosis of the now rare epiglottitis, which should be considered to be immediately life threatening.

Illnesses rarely requiring hospital admission

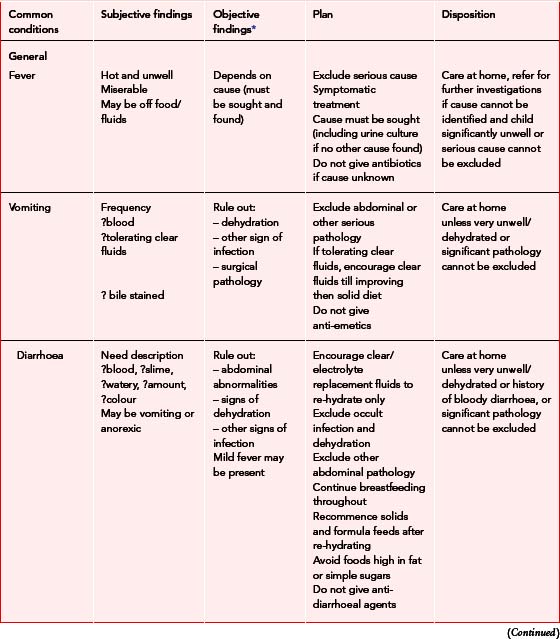

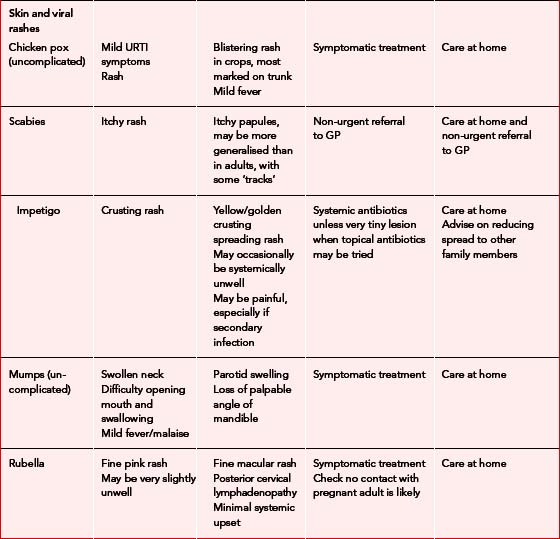

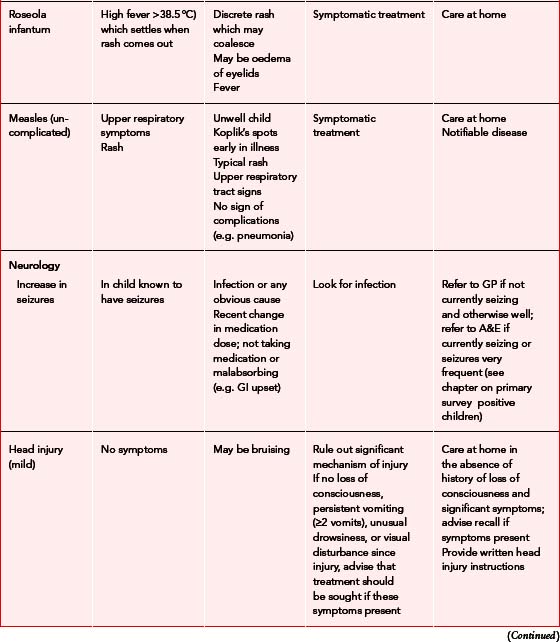

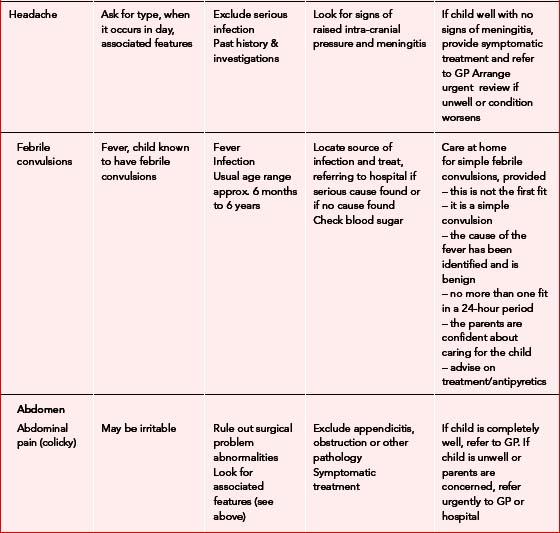

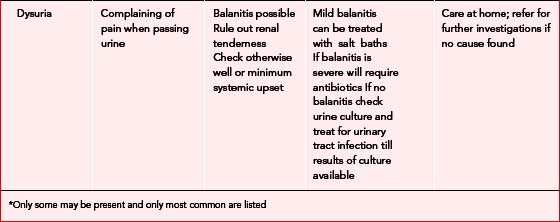

Table 6.1describes common illnesses and presentations in children that rarely require hospital admission. Upper respiratory tract infections are particularly common in children, but foreign bodies in the airway should always be considered as a possible explanation of mild stridor or wheeze in otherwise well children. Children are also susceptible to a wide range of viral infections, many of which present with rashes of various descriptions.

To hospitalise or not?

In many situations it can be difficult to decide whether to send children to hospital because they fall neither into the category of ‘primary survey positive patients’ nor that of the relatively well child described in Table 6.1. The signs of serious illness in children are subtle and it is usually wise to err on the side of safety and ask for a second opinion if in doubt. However, some evidence-based pointers that may be helpful in deciding whether hospital referral is necessary are given below.2

Poor fluid intake or vomiting, particularly if in association with:

Disposition flow chart

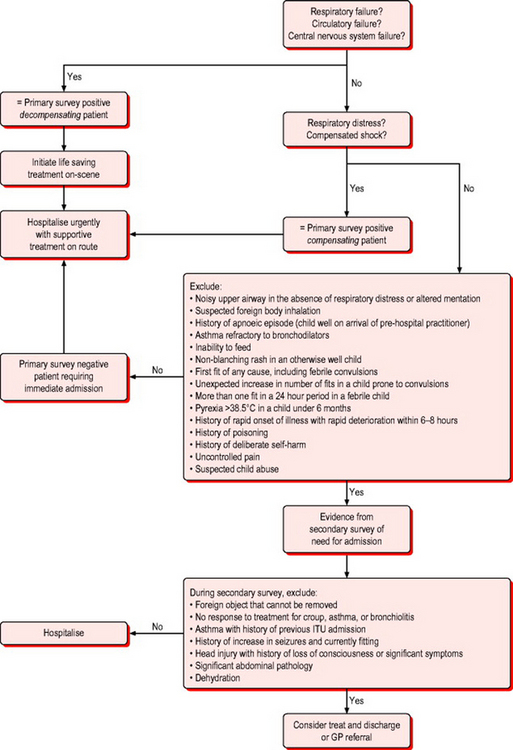

Figure 6.2 shows the decision-making process for determining the urgency of care required and the appropriate disposition for children with a range of presenting problems.

Technologically assisted children

Tracheostomy tubes

In the event that a tracheostomy tube becomes obstructed, the following approach should be adopted:

Ventriculoperitoneal shunts

Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts are surgically implanted in children with hydrocephalus to allow drainage of cerebrospinal fluid. Obstruction of the shunt will result in raised intra-cranial pressure, the signs of which will include altered affect, high pitched cry, fitting, and falling level of consciousness, similar to the presentation of meningitis. Children with evidence of an obstructed shunt require urgent hospital admission. The presence of Cushing’s triad (bradycardia, hypertension and Cheyne–Stokes ventilation) indicates the ICP is so high that brainstem impairment is occurring and is a critical situation. Supportive care should be provided during transfer to the hospital. If the child is very ill this will include airway care and high concentration oxygen therapy. Controlled hyperventilation (at a rate of 5 inflations per minute above the child’s normal respiratory rate) should be used only in children with signs of Cushing’s triad. Most children present sooner than this because parents have been trained to look for warning signs (and sometimes to check the shunt) and less rapid transfer will be more suitable.

Obstruction

Infected site

Appendix: pharmacopoeia

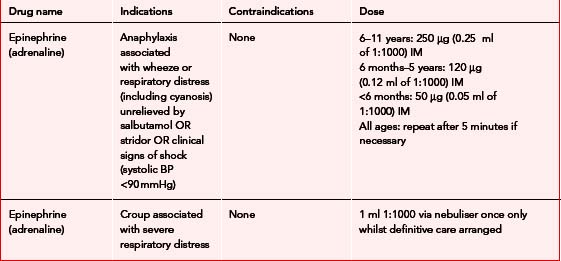

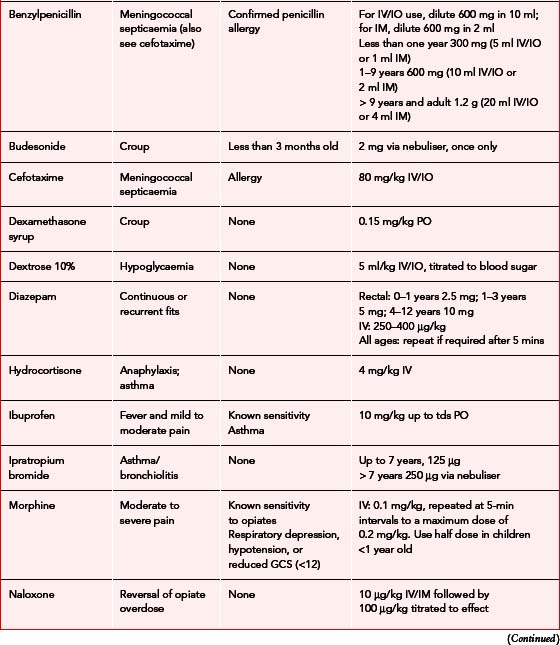

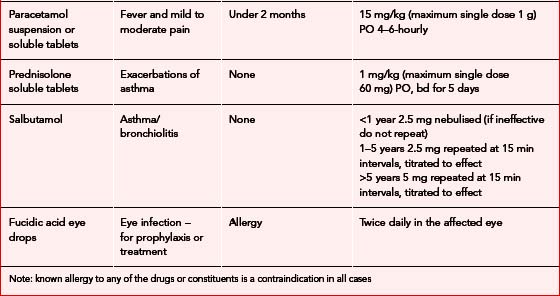

Table 6.3 describes the indications, contraindications and doses of drugs commonly used to treat illness in childhood.

1 Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Diagnosis and management of childhood otitis media in primary care. In Section 3: Medical treatment. Edinburgh: SIGN; 2003. Available online http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/66/section3.html (5 Mar 2007)

2 Paediatric Accident and Emergency Research Group. Evidence based guidelines for acute management with breathing difficulty, diarrhoea & vomiting, post-seizure. Cheltenham: Children Nationwide, 2002.

4th edn. Advanced Life Support Group, editor. Advanced paediatric life support. The practical approach. BMJ Books, London, 2002.

2nd edn. Advanced Life Support Group, editor. Pre-hospital paediatric life support. The practical approach. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 2005.

American Academy of Pediatrics, editor. Pediatric education for prehospital professionals. Jones and Bartlett, Sudbury, MA, 2000.

Behrman RE, Kliegman R, Nelson T. Essentials of paediatrics. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 1990.

Gill D, O’Brien N. Paediatric clinical examination made easy, 4th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2003.

Morley CJ, Thornton AJ, Cole TJ, Hewson PH, Fowler MA. Baby Check, 2000. Available online http://nicutools.org (5 Mar 2007)

Ninnis N, Glennie L. Lessons from research for doctors in training. Bristol: Meningitis Research Foundation, 2004.