Chapter 33 Childhood emergencies

The child in the emergency department presents a challenge to the busy emergency physician, particularly in a setting where both adults and children are being treated and the general culture is not a paediatric one. Children are different in that they are dependent, developing and growing rapidly (see Table 33.1). They also differ in their spectrum of disease and response to illness.

Table 33.1 Normal respiratory rate and cardiovascular values

| Age | Normal respiratory values (breaths/min)∗ | Normal cardiovascular values (beats/min)∗∗ |

|---|---|---|

| Infants | 40 | 160 |

| Preschool | 30 | 140 |

| School age | 20 | 120 |

∗ Endotracheal tube size = (age in years ÷ 4) + 4

∗∗ Blood volume = 80 mL/kg; systolic blood pressure = 80 mmHg + (age in years x 2)

RESUSCITATION

In the emergency situation, a child’s condition can deteriorate very rapidly. This is due to:

There may also be a greater risk of acute deterioration in the following cases:

Respiratory

Increased breathing effort is a sign of increasing respiratory insufficiency and is characterised by: tachypnoea, use of accessory muscles, expiratory grunting, stridor, wheezing, nasal flare, dyspnoea and cyanosis. Other important but often forgotten signs of impending respiratory embarrassment in children are exhaustion and apnoea.

|

CNS

AIRWAY EMERGENCIES

Croup

Croup is viral laryngotracheobronchitis characterised by a barking cough. Often several days of upper respiratory tract symptoms precede the cough. The associated respiratory distress is worse at night and with anxiety in child or parent. Spasmodic croup occurs without accompanying infective symptoms and is often recurrent. Stridor at rest is an indication of severity, while cyanosis is a pre-arrest state. Lateral airways X-rays are not needed and are dangerous as the child is unstable.

A calming environment with the child on the mother’s lap is therapeutic.

Foreign body inhalation

This causes an acute onset of respiratory distress, often in a child between 6 months and 2 years. If the object is in the upper airway, complete or partial obstruction may be present. If the child is moving air or coughing, removal under inhalational anaesthetic by skilled personnel is advisable. If the airway is completely obstructed, rapid back blows in an infant or the Heimlich manoeuvre in an older child should be performed. Direct visualisation and removal of the object with Magill’s forceps may be possible. If this is not successful, a needle cricothyroidotomy should be performed. Cricothyroidotomy using a scalpel is not recommended for children under 5 years.

RESPIRATORY EMERGENCIES

Pneumonia

THE UNCONSCIOUS CHILD

Always examine the whole child in the light of a thorough history.

Immediately

THE FEBRILE CHILD

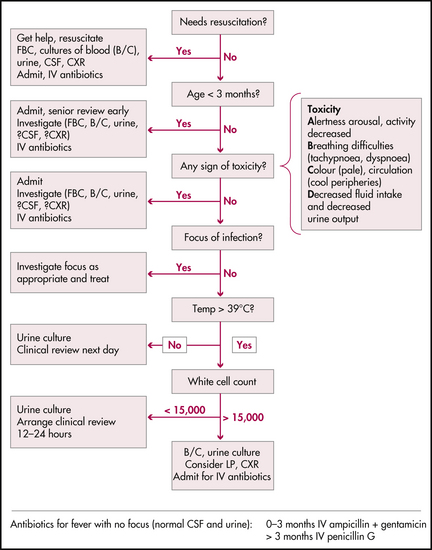

If the cause is still not evident consider intussusception (may have a ‘cerebral’ presentation). Fever is one of the most common causes of presentation to an emergency department. Most fevers are due to viral infections, but care must be taken to exclude a bacterial infection. Diagnosis can often be difficult, particularly in the younger child where caution is advised. The child without a clear focus presents a real challenge, with pneumococcal and meningococcal infections being the most common infective condition encountered. Various approaches are advised in the literature, ranging from cautious assessment and observation through to aggressive management (see Figure 33.1).

Figure 33.1 Flowchart for an infant with fever

NSW Health, Acute management of infants with fever. Assessment and management: flowchart for child < 3 years old with fever (> 38°C) axillary, p 4

Factors to consider when assessing a febrile child:

Is the child toxic?

A is for arousal, alertness and activity.

B is for breathing difficulties.

C is for poor colour (pale) and poor circulation (cold peripheries).

Children with a definite focus of infection should have specific investigations of that focus unless they are very young or toxic. Very young and toxic children require empiric antibiotics and a full septic work-up in that order. Remember, in some conditions such as meningococcaemia, delay in the administration of antibiotics may result in a poor clinical outcome. A full septic work-up consists of blood count, blood cultures, chest X-ray, urine culture and lumbar puncture. Antibiotic choice depends upon your patient population and local resistance rates. The antibiotics listed in Table 33.3 are suggested only as a starting point; we strongly recommend you discuss this with your infectious disease consultant.

Table 33.3 Initial choice of antibiotics in the child with fever

| Condition | Age | Antibiotic |

|---|---|---|

| Fever with no focus |

What else could it be?

Always think of underlying metabolic, cardiac and endocrine problems. The fever may be the simple harbinger of acute deterioration in these patients. One possible approach to management of the febrile child is given in Figure 33.1.

Follow-up

All children who are discharged home from the emergency department with fever should be followed up the next day, either in the emergency department or by the family doctor. This is to detect progression of infection, response to treatment and results of investigations.

COMMON INFECTIONS

Aspirin for the management of fever is contraindicated in childhood.

CONVULSIONS

Is the seizure a simple uncomplicated febrile convulsion? Is there a treatable cause?

Management principles

General management

GASTROENTERITIS

Gastroenteritis is a common childhood complaint, the commonest complication of which is dehydration.

Organisms to consider include:

Most cases will be viral. Bloody diarrhoea often suggests a bacterial cause.

Signs include vomiting, diarrhoea, fever and abdominal pain. The diarrhoea with rotavirus and adenoviruses often lasts for 5–12 days, and that of bacterial diarrhoea (especially Campylobacter) is often bloodstained. Giardia infection commonly causes an epidemic and is complicated by asymptomatic carriers. Beware of attributing vomiting without diarrhoea to gastroenteritis.

FLUID THERAPY

REHYDRATION

Acute resuscitation of the child with cardiovascular compromise should include a bolus of fluid 20 mL/kg of crystalloid such as normal saline or Hartmann’s solution or 5% normal serum albumin (NSA) colloid. Half normal (N/2) and quarter normal (N/4) saline should not be used for resuscitation.

Volume required to replace the fluid deficit can be estimated using:

DIABETIC KETOACIDOSIS AND HYPOGLYCAEMIA

Management

Hypoglycaemia

Management

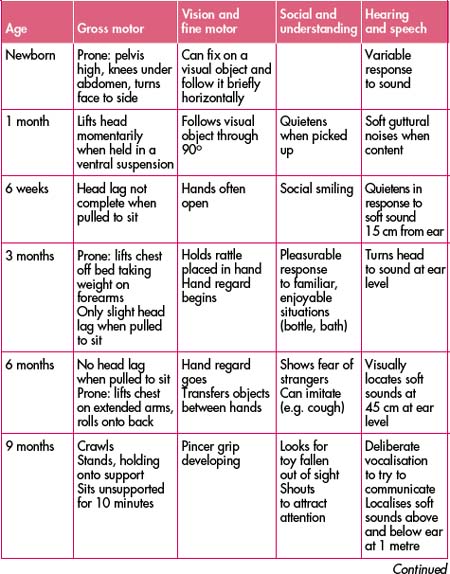

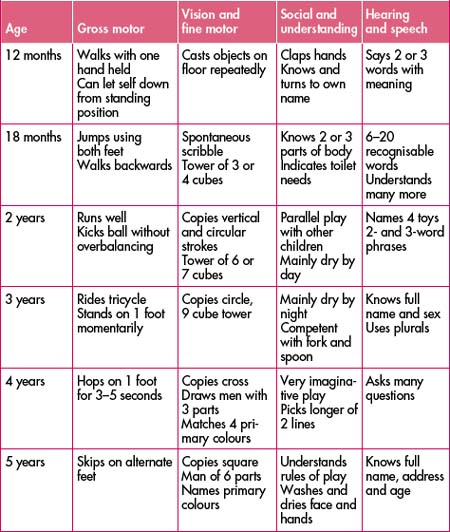

DEVELOPMENT

Assessing normal development is a skill acquired only from constant practice and observation. Always consider seriously parents’ concerns of loss of recently acquired skills or slow development of others. If you are not confident of your own skills in assessing development do not dismiss parents’ concerns but rather refer appropriately. See Table 33.4 for the normal development milestones.

FEEDING

It is important to be familiar with basic feeding practices and to be able to support a breastfeeding mother through a crisis when her child is unwell. Milk allergies and intolerances are not common. Resist changing milk formulas for the lack of better inspiration. Rather than give inappropriate advice, refer the infant and mother to their local doctor, paediatrician, community health centre or, in some instances, an appropriate mothercraft centre.

THE INCONSOLABLE INFANT

Consider physical causes of pain and discomfort, especially treatable conditions such as:

JAUNDICE

CHILD ABUSE

Suspect child abuse if

Management

SUDDEN INFANT DEATH SYNDROME (SIDS)

Resuscitation attempts are dictated by the clinical situation. Be alert for a treatable condition.

Photographs and hand and foot prints are often appreciated at a later date.

Follow-up for the parents is important. This may need to be organised later.

SURGICAL ABDOMINAL EMERGENCIES

Hirschsprung’s disease

Hirschsprung’s disease is absence of intramural ganglion cells, usually in the rectosigmoid region. It is four times more common in males. It presents early in life with increasing constipation and abdominal distension from the newborn period to early childhood. Rectal examination often reveals explosive release of stool under pressure. Abdominal X-ray shows faecal loading. The complications are enterocolitis and perforation. The treatment is surgical.

ORTHOPAEDIC PROBLEMS

Pulled elbow

A pulled elbow occurs when the radial head is pulled out of the annular ligament sling with traction on the arm. It sometimes occurs recurrently in children between 1 and 4 years. Check that the story is consistent with this diagnosis, and exclude bony injury with X-ray. To relocate the annular ligament, feel over the radial head, and firmly supinate and extend the arm. Often a click is felt and the child begins using the arm within 10 minutes. If this does not occur, check that nothing has been missed and arrange review the following day. The natural history is for these to spontaneously relocate over a few days.

PAIN MANAGEMENT

Sedatives

Ketamine, a dissociative anaesthetic given IV or IM, is very effective. Paediatric airway expertise should be present as should venous access. The airway is maintained but there is an increase in salivation. Its side effects include occasional prolonged vomiting and hallucinations. This agent is not commonly used in paediatrics but may be useful in the adolescent.

PROCEDURES

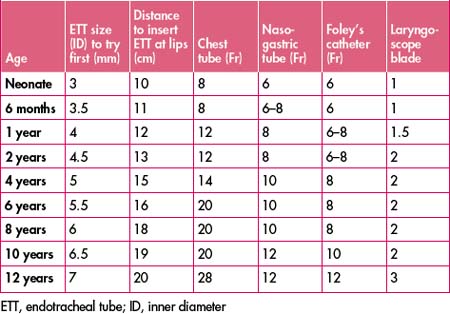

What size tube?

Most items of equipment vary depending upon the age, weight and size of the patient. Table 33.5 provides only a guide to the size of commonly used items of equipment for use in emergency circumstances. In certain circumstances it may be necessary to modify the tube size (e.g. a child with croup may need a smaller tube).

Obtaining blood

It is always possible to get sufficient blood from paediatric patients for all tests—it is a matter of patience, having the right equipment and technique. Depending on the laboratory, you may be able to use smaller samples. A superficial peripheral vein is the preferred location. If inserting an IV line, plan your investigations so that you can take blood for investigations at the same time to avoid unnecessarily hurting the child. Use topical EMLA if time allows.

Urine sampling

To adequately diagnose a urinary tract infection, a sterile sample must be collected. Midstream urines are only of value in the older child. Bag urines are inadequate. Younger children require either a suprapubic aspirate or catheterisation. Over 1 year catheterisation is preferred.

Suprapubic aspiration

Lumbar puncture

Baren J., Rothrock S., Brennan J., et al. Pediatric emergency medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2008.

Browne G., Choong R.K.C., Gaudry P.L., Wilkins B.H. Principles and practice of children’s emergency care. Sydney: Maclennan and Petty; 1997.

Cameron P., Jelinek G., Everitt I., et al. Textbook of paediatric emergency medicine. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2006.

Crain E., Gershel J. Clinical manual of emergency pediatrics, 4th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2003.

Hewson P., Oberklaid F. Recognition of serious illness in infants. Modern Medicine of Australia. 1994;37(7):89-96.

Kilham H., Isaacs D., editors. The Children’s Hospital at Westmead handbook: clinical practice guidelines for paediatrics. Sydney: McGraw-Hill, 2003.

National Health and Medical Research Council. The Australian immunisation handbook. 8th edn. NHMRC; 2003. Online. Available: http://immunise.health.gov.au/handbook.htm.

Strange G., et al. Pediatric emergency medicine, 2nd edn. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2002.