Child Maltreatment

Perspective

Child maltreatment is an all-encompassing term that includes all forms of child abuse: physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, child neglect (physical, emotional, educational), and factitious disease by proxy (also known as Munchausen syndrome by proxy and most recently termed medical child abuse).1,2 Although the recognition of these conditions by the medical community has occurred at different times, the pivotal report describing child physical abuse, published in 1962, was the article “The Battered Child Syndrome” by Kempe and colleagues.3 The article noted the presence of a complex of physical findings, including fractures, cutaneous bruises, and internal injuries. Since that time, multiple articles and books have described the spectrum of the disorders. During the 1980s, much of the literature focused on child sexual abuse, including the refinement of understanding of normal anogenital anatomy of prepubescent children.4 Child sexual abuse is defined as the involvement of children and adolescents in sexual activity to which they cannot give consent based on their developmental level, involving an age disparity between the victim and the perpetrator, and for the sexual gratification of the older individual. Child sexual abuse may involve physical contact between the child and the adult or the involvement of the child in other activities, such as photography or the production of pornographic material.

Epidemiology

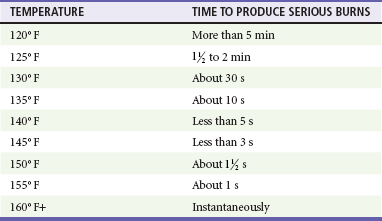

Just under 1 million cases of suspected child abuse and neglect are reported annually in the United States. Table 66-1 summarizes the data by category of abuse or neglect as noted by the 2009 Child Maltreatment report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.5 Although child abuse occurs across the spectrum of race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic class, certain factors are associated with an increased prevalence of abuse, including poverty, social isolation, parental alcohol and substance abuse, parental mental illness, and domestic violence.6,7

Table 66-1

Overview of Incidence of Child Abuse

Data from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children, Youth and Families: Child Maltreatment 2009. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. Available at http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/stats_research/index.htm#can. Accessed January 11, 2013.

Principles of Disease

Bruises may appear as petechiae or ecchymoses. They occur at the point of impact between the striking object, such as the hand, and the child’s body. Often they mirror the form of the inflicting object and may appear as a hand print, a belt outline, or a mark resembling another object (Fig. 66-1). These bruises are referred to as patterned injuries. When the blow occurs at high velocity, the bruising may resemble the outline of the object as the soft tissue in the center of the impacted field moves laterally (negative image). When the thrust of the strike is slower, the central portion of the skin also may be discolored (positive image). The extent of an injury is influenced by many factors, including the force of blow and the area struck. Frequently, the struck area initially is only erythematous, swollen, or tender, and 24 hours may elapse before bleeding into the skin and subsequent discoloration are noted. The degree of discoloration and the rapidity of resolution of the discoloration are influenced by the location of the injury; large fat pads or muscle masses, such as the buttocks, can hold larger volumes of blood, and resolution takes longer. In general, extravasated blood goes through a predictable color change pattern as it resolves, progressing from purple to green to yellow and eventually to brown. However, the color of a bruise should not be used as a tool to estimate the age of a bruise.8,9 Accidentally incurred bruises tend to occur over bony prominences, such as the shin and forehead. In addition, nonambulatory children (<1 year old) do not readily sustain accidental cutaneous injuries (“those who don’t cruise, don’t bruise”).8 Bites also produce a patterned injury. The distance between the maxillary canine teeth helps establish whether the perpetrator was a child (<2.5 cm), which is often alleged, or an adult (>3 cm) (Fig. 66-2).10

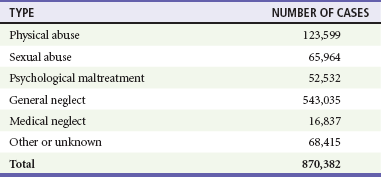

Burns may be inflicted through contact with a dry hot object or through immersion in hot water. One common type of inflicted burn occurs secondary to contact with a cigarette. Inadvertent contact with a lit cigarette tends to create less severe or linear burns; however, inflicted cigarette burns are usually circular, measuring 8 to 10 mm (Fig. 66-3). Initially they have a blistered appearance but then become ulcerated and crust over. Burn injuries also may assume a patterned appearance resembling the configuration of the hot object, such as a heating grid or an iron. Immersion burns occur when a child or infant is placed in hot water. Such burns often involve the anogenital area and may represent punishment for toilet training accidents, or they involve hands or feet (glove-stocking distribution) that have been dunked in hot water. Immersion burns are usually second-degree burns (Fig. 66-4). The extent of the burn is influenced by the temperature of the water, the body site exposed (the skin is thinner in certain areas, such as the anogenital region), the age of the individual (younger children and elderly adults have thinner skin), and the duration of the contact between the hot object and the skin (Table 66-2).11 Burns caused by contact with viscous liquids, such as grease, oils, or syrups, may be more severe because such liquids are more adherent to the skin surface. Chemical burns may occur through contact with corrosive products, including industrial-strength cleaning agents.

Accidental burns can occur in children and usually involve scald injuries, which happen when children spill hot liquids, such as coffee, on their clothes and skin. Spill burns have a characteristic drip appearance, with more extensive and severe injury proximal to the point of contact and less extensive and milder injury more distally (Fig. 66-5). Disposable diapers are very absorbent of heat as well as of liquids. Scald burns in the anogenital area that are attributed to hot beverages falling into a child’s diaper should be scrutinized carefully, and if there is any concern of abuse, a report should be made by anyone who is considered a mandated reporter such as a paramedic, nurse, physician, or social worker.12,13 The report is made to child protective services or law enforcement. Many jurisdictions have a “child abuse hotline” to facilitate such reporting.

Skeletal injuries may involve any of the bones in the body. Although approximately 42% of boys and 27% of girls have sustained a fracture before the age of 16 years, certain fractures are highly suspicious of an inflicted injury (Table 66-3).14,15 In particular, metaphyseal fractures, rib fractures, and certain types of skull fractures should raise concern about inflicted trauma (Fig. 66-6). Metaphyseal fractures (i.e., classic metaphyseal lesions) occur because of yanking or pulling on an extremity. On radiographs they may appear as metaphyseal chips or what is referred to as a bucket-handle injury of the metaphysis of the long bone. They are characterized by the absence of callus as they heal (Fig. 66-7). They usually are noted in children younger than 2 years. Long bone fractures involving the lower extremities are equally concerning in preambulatory children. Once children are ambulatory, accidental injuries such as toddler factures (nondisplaced spiral fractures of the distal tibia) are not uncommon. Rib fractures, particularly posterior rib fractures in an otherwise healthy infant, are virtually pathognomonic for inflicted injury16 (Fig. 66-8). The rib cage, because of its archlike structure, must be subjected to a good deal of force for disruption to be caused. Rib fractures are extremely uncommon as a consequence of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and are not reported across the age spectrum. In addition, there is no evidence that chest encirclement for CPR is more likely than two-finger sternal compression to cause rib fractures.17 The presence of multiple skull fractures or skull fractures in the occipital region is unusual in cases of accidental trauma and should raise concern for inflicted trauma. Fractures that are diastatic (>3 mm in width) or grow in size are less specific as markers for nonaccidental trauma; however, they are usually associated with mechanisms of injury that involve greater traumatic forces.

Table 66-3

Figure 66-6 Complex skull fracture associated with child maltreatment. (Courtesy Sara T. Stewart, MD, MPH.)

Head injuries, including those associated with the classically described “shaken baby syndrome,” account for most child abuse–related fatalities. The syndrome includes evidence of head trauma in association with retinal hemorrhages and skeletal injuries and occurs generally in infants younger than 1 year but may be seen in children up to 3 years old. Often, there is no evidence of an impact injury to the head, such as a scalp hematoma or skull fracture.18,19 If impact occurs, it may be against a soft or compressible surface, such as the mattress of the crib. Such an impact results in a rapid deceleration of the head, and the brain experiences a coup-contrecoup injury by moving back and forth within the confines of the skull. Some infants have been subjected to multiple episodes of shaking.20 Shaking of an infant or young child subjects the brain to rotational acceleration, which is capable of generating greater force and speed than linear acceleration, which is the type of acceleration that occurs with a fall. It has been postulated that severe repeated shaking of an infant or young child can lead to disruption of the neuronal cells, with or without the presence of either subarachnoid or subdural hemorrhage. Hemorrhage is a marker for the event but may be of limited clinical significance, and death, when it occurs, may not be related to bleeding, brain compression, or brain displacement. Injury to the brain cells is referred to as traumatic axonal injury. This injury results in disruption of the cell membrane and subsequent cerebral edema. Cerebral edema impedes the cerebral circulation, which results in further hypoxic damage to the brain. At autopsy, special staining techniques allow for the recognition of axonal injury, which may be diffuse (diffuse axonal injury).21,22

Retinal hemorrhages are another common associated finding and are reported to be present in about 85% of cases of shaken baby syndrome. Approximately two thirds of these children have retinal hemorrhages that are multilayered, are too numerous to count, and extend to the periphery of the retina (Fig. 66-9). The pathophysiology of retinal hemorrhages is uncertain. Current evidence points to vitreoretinal traction as a significant factor in causing retinal hemorrhage as an infant’s head undergoes forceful rotational movement in which centrifugal forces are generated. It is unclear what role other factors, such as increased intracranial pressure and hypoxia, may have on the development of these hemorrhages as well. Hemorrhages may involve the vitreous in front of the retina, and retinal hemorrhages are categorized as preretinal, intraretinal, or subretinal. More superficial intraretinal hemorrhages that spread between nerve fibers may be described as flame or splinter hemorrhages, and deeper intraretinal hemorrhages may be described as “dot” or “blot” hemorrhages. Clinically, the hemorrhages may be localized or may extend to the ora serrata (the retinal edge). Extensive retinal hemorrhages have been shown to not result from typical resuscitation efforts but can occur from severe accidental mechanisms associated with rotational head movement, such as rollover motor vehicle collision or crush injuries to the chest with massive increase in intrathoracic venous pressure (Purtscher’s syndrome).23

Figure 66-9 Retinal hemorrhages in an infant with shaken infant syndrome. (Courtesy Carol Berkowitz, MD.)

Abdominal trauma accounts for about 10% of injuries in abused children and carries a sixfold higher mortality rate than abdominal trauma caused by accidental means.24 Trauma is often blunt and includes blows and kicks to the abdomen. Frequently, there is no external evidence of the injury because the force has been transmitted to the intra-abdominal structures. Injuries that include hematomas or lacerations can occur to the liver or less commonly to the spleen. In addition, children may develop duodenal hematomas, an injury that leads to symptoms of upper intestinal obstruction. Perforations of the intestine or other hollow viscera can follow a blow to the abdomen, with subsequent progression to secondary peritonitis. Pancreatitis is also a sequela of inflicted abdominal trauma, which is said to be the most common mechanism of non–medication-associated pancreatitis in children. Pancreatic pseudocyst may develop as a complication of such trauma.25

Child Sexual Abuse

Physical findings present when a child or adolescent has been sexually abused depend on the nature of the abuse, the time since the abuse, and whether the abuse was repetitive or isolated. Acute injuries include disruptions (tears) of the hymen, petechiae, hematomas, or tears of other genital structures. The prepubescent hymen is significantly more fragile and more easily traumatized than the postpubertal hymen, which thickens and becomes redundant under the influence of estrogen. Physical changes in the anogenital area also may be noted when there has been prior or recurrent sexual abuse. Changes include loss of hymenal tissue and the appearance of U-shaped disruptions in the hymenal contour. Anal findings include the presence of scars and changes in anal tone and the anal contour.26 Evidence of recent trauma also may be visible in the anal area. Acutely, there may be lacerations that appear as perianal fissures, which are characteristically wider distal to the anus. There may be post-traumatic dilation, or alternatively, anal spasm may occur in response to submucosal injury. In abused boys the penis rarely has a noticeable injury.

Clinical Features

Child Physical Abuse

Children who have been physically abused may have complaints related to the abuse, or injuries may be noted during the course of an evaluation for an unrelated medical condition. Infants with head injuries may have nonspecific signs that go unrecognized as being related to inflicted head trauma. These signs may include apnea, altered mental status, an apparent life-threatening event, vomiting, or a seizure. Clinicians should remain alert that these signs may be related to intracranial bleeding or elevated intracranial pressure.27 A careful physical examination should include an attempt to visualize the eyegrounds to determine if there is any evidence of retinal hemorrhages. Bruises on a young infant’s face are suspicious for head injury (Fig. 66-10).

Children with abdominal injuries may have abdominal pain, vomiting, abdominal distention, or shock. In cases of inflicted trauma, the history may be unrevealing or may be inconsistent with the medical findings. It is common for a parent to state that he or she is uncertain how a child sustained the injury or that the child was well at bedtime and awoke in the morning refusing to walk or had severe abdominal pain. Caregivers should be queried about how they think the injury was sustained. In cases of inflicted head trauma, the scenario often includes a young infant left in the care of a male friend or partner of the mother who has gone to work or to run errands. The male companion asserts that the infant was fine, sleeping in the crib when he went to take a shower or make some coffee, and when he returned to check on the infant, the infant was not breathing or was seizing. Often the mother is called before the individual calls 911, or the infant is scooped up by the individual and carried to a hospital. The part of the history that is omitted is that the infant was crying and the companion shook the infant and thrust him or her back into the crib. The infant sustained acute traumatic axonal injury and stopped crying. The infant was then left unattended, seemingly asleep. As bleeding and cerebral edema develop, other symptoms intervene. Sometimes a family member fallaciously relates a history of a fall, usually from a height (<25 inches from the ground) to a floor that is often carpeted. Or the family member may relate that a young sibling hit or jumped on the infant. Such events are not consistent with severe intracranial injuries.28 Histories of falls also are related in children with severe inflicted abdominal trauma. Although falls may lead to bruises of the abdominal wall and rarely damage to solid organs, they are unlikely to cause intestinal injury, such as duodenal hematomas or intestinal perforations.29 Other mechanisms of abdominal injury include those related to seat belt restraints or an impact with handlebars. The latter is associated with pancreatic trauma. In addition to the history of the current event, past medical, developmental, and social histories are important. In children with acute injuries consistent with physical abuse, there is the possibility that the findings or their severity may be related to an underlying medical condition. A careful medical history may help exclude such conditions or bring these disorders into consideration. A history of epistaxis and bleeding gums in a child with bruises suggests an underlying coagulopathy. A family history of fractures raises the possibility of a bone disorder, such as osteogenesis imperfecta. Documenting a developmental history is important in attempting to assess the likelihood that children’s injuries were related to their own activity. It is crucial to be suspicious of injuries in young infants who have limited motor skills. A caregiver may allege that a 3-week-old infant sustained a head injury when he or she fell after having been placed in the center of the bed, but a 3-week-old infant is developmentally unable to scoot or roll from the center to the edge of the bed. The developmental history should document major motor milestones, such as age of rolling over, sitting unsupported, crawling, and walking.

Child Sexual Abuse

The physical examination should include a full head-to-toe assessment to determine if there are acute nongenital injuries (e.g., grip marks or oral injuries) or dermatologic conditions, such as lichen planus, which may explain changes in the anogenital area. The anogenital examination should note the level of pubertal development; whether the child is prepubertal or at a more advanced stage of sexual maturity should be recorded. Prepubertal children should be examined with use of a multimethod approach.30 Initially, children should be evaluated in the supine position. The labia majora and surrounding tissues should be assessed for evidence of injuries or other abnormalities. Separation or traction should be applied to the labia to visualize the structures covered by the labia majora. In prepubertal children the labia majora are large and full and cover the underlying area. The labia minora are small and delicate and do not fully encircle the vaginal orifice. The clitoris and urethra should be examined. The hymen should be inspected visually for evidence of disruptions and irregularities. The hymen should be precisely described—the phrase “hymen intact” is not sufficiently descriptive for the purposes of a forensic medical assessment. An appropriate description would be “hymen pink, annular, with smooth thin edge and no disruptions.” The hymenal diameter is difficult to measure reliably, and an enlarged hymenal orifice without other changes in the hymen is not thought to have forensic significance. Girls also should be examined in the prone knee-chest position; however, young prepubertal girls may have difficulty holding this position. The hymen often relaxes more fully in the knee-chest position, allowing for a more thorough assessment. Speculum examinations are neither indicated nor appropriate for a prepubertal child. If intravaginal trauma is suspected on the basis of vaginal hemorrhage, examination of the child in the operating room with anesthesia is mandatory. Postpubertal adolescents should be examined on a traditional pelvic examination table with stirrups. In cases of acute sexual assault, a full evidentiary assessment, including the collection of forensic material, is indicated.

Diagnostic Strategies

Urinalysis, liver function studies, and serum amylase and lipase levels should be considered in children with symptoms of abdominal injury, such as vomiting, abdominal pain, or guarding, though the sensitivity of such studies is limited.31 Plain x-ray films are rarely helpful but should be considered if clinical findings suggest perforation or obstruction. Computed tomography scan of the abdomen is a more precise way of delineating any abdominal injury. Computed tomography scan of the head is indicated when symptoms are consistent with head trauma or in an infant with facial bruising. Computed tomography scans may reveal extra-axial hemorrhage or findings consistent with cerebral edema. If the child is sufficiently stable, magnetic resonance imaging is helpful in determining the age of the hemorrhages and in assessing whether there has been prior intracranial hemorrhage. Magnetic resonance imaging also eliminates ionizing radiation exposure related to computed tomography scans of the head.

In recent years, certain metabolic disorders have been described that also may be associated with intracranial hemorrhage. In particular, glutaric aciduria type I may be mistaken for inflicted head trauma.32 Urinalysis for organic and amino acids would detect this condition.

Child Sexual Abuse

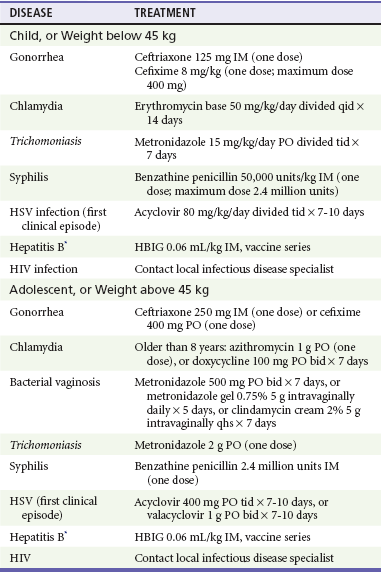

Evaluating a child or adolescent for the presence of a sexually transmitted infection (STI) depends on many factors, including disease prevalence in the community, patient symptoms, and the nature of the abuse. In cases of acute assault, the recommendation is often to treat the adolescent patient prophylactically against gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomoniasis. The prepubertal child, however, is at lower risk of acquiring an STI from abuse or assault, and prepubertal girls are at lower risk of developing ascending pelvic infection from an STI. As a result, if the prepubertal child is available for follow-up visits, prophylaxis for gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomoniasis may be deferred. The decision to offer prophylaxis against human immunodeficiency virus is often based on disease prevalence and other risk factors and should be made in conjunction with an infectious disease consultant (Table 66-4).33

Table 66-4

Sexually Transmitted Infection Prophylaxis or Treatment after Sexual Abuse/Assault

*Unimmunized child and perpetrator with acute hepatitis B infection.

Adapted from Workowski KA, Berman SM: Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR 59:1, 2010; and 2009 Red Book: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 28th ed. Elk Grove, Ill, American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009.

Differential Considerations

Areas of congenital dermal melanocytosis (formerly called mongolian spots) are bluish discolorations that are seen normally over the buttocks and lower spine in children with darker complexions (Fig. 66-11). These spots can appear on other parts of the body, such as the face and upper arm. They are usually present from birth but may not appear until the infant is several weeks old. When seen in a typical location, they are readily recognized, but when located elsewhere on the body, they may be mistaken for bruises. Bruises resolve over time; however, these spots remain unchanged (do not go through purple-green-yellow-brown transformation) because they are undistributed melanocytes.

Figure 66-11 Dermal melanocytosis in an infant. (Courtesy EMSC Slide Set, National EMSC Resource Alliance.)

Phytophotodermatitis also may be mistaken for bruises or burns. This condition is the result of a phototoxic reaction that develops on sun-exposed areas of the body that have been in contact with certain fruits or juices such as lime or lemon juice. The lesion initially appears as erythema and blistering and evolves to a brown discoloration, which may take the shape of the dripped juice or the object with which the juice came in contact (Fig. 66-12). For instance, if a mother is making lemonade, has the lemon juice on her hand, and holds her child, a brown discoloration in the form of a handprint may appear if the child is in the sun. These lesions fade over time, and with a careful history and physician familiarity with the condition, the correct diagnosis can be made.

Fractures may occur unintentionally. In young infants, fractures may be a result of birth-related injuries. The most common fractures sustained during birth are clavicular and humeral fractures. These fractures may not be appreciated immediately after birth but become apparent when callus formation is noted. Ambulatory children may sustain fractures related to falls. A toddler’s fracture, also referred to as a CAST fracture (childhood accidental spiral tibial fracture), occurs when there is a twisting injury to the tibia as the child falls on it.34 Often, this fall was not witnessed or was not noted by the caretaker as being significant trauma, so the child may have no reported history of trauma. Typically, the fracture is a nondisplaced distal fracture of the tibia that is detected when a child demonstrates a limp. Sometimes the fracture may not be apparent on the initial radiograph, but delayed radiographs (1-2 weeks after injury) may show callous formation or a bone scan may show the presence of increased bony uptake in the area of the fracture.

Fractures occur with increased frequency and with lower amounts of force in certain conditions. Premature infants may experience osteopenia of prematurity (sometimes referred to as rickets of prematurity), the radiographic appearance of which can be mistaken for a metaphyseal fracture.35 In addition, osteopenic bones may fracture more easily. More advanced cases of osteopenia can be noted on a plain film of the bones. Osteogenesis imperfecta is a condition in which the bone is more brittle and easily disrupted.36 There are multiple types of osteogenesis imperfecta, each with a different gene frequency. The overall incidence of osteogenesis imperfecta is 1 in 20,000. In general, osteogenesis imperfecta is associated with other clinical findings, such as blue sclerae and brown discoloration of the teeth (dentinogenesis imperfecta). Rarely, bone fragility may be present in isolation. Scurvy, congenital syphilis, and congenital rubella are associated with bony changes that may be misinterpreted as evidence of prior bony injury.

Child Sexual Abuse

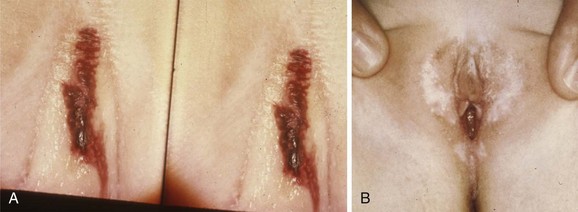

Numerous medical conditions may be misdiagnosed as child sexual abuse. Accidental trauma, most commonly straddle injuries, may occur after a fall onto the perineum. Such falls occur with climbing on monkey bars, riding on boys’ bicycles, or exiting from a swimming pool. Straddle injuries usually involve the more external structures, including the labia minora, labia majora, and periurethral area. The hymen remains uninjured. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is a dermatologic condition of unclear cause that affects prepubertal girls and boys and postmenopausal women. The hymen is unaffected, but the adjacent skin becomes atrophic and may sustain blood blisters or petechiae (Fig. 66-13A). Characteristically, the skin in the perianal and perihymenal areas becomes hypopigmented and surrounds these orifices with a pale figure-of-eight configuration (Fig. 66-13B).

Urethral prolapse characteristically affects African American girls aged 5 and 8 years. The mucosal lining of the urethra slides forward and protrudes from the urethral orifice, appearing as an erythematous, edematous mass (Fig. 66-14). Symptoms include pain and bleeding. Management may involve sitz baths, antibiotic ointment, or referral to a urologist for ligation. Vaginal discharge may occur secondary to conditions other than STIs. Shigella, group A beta-hemolytic streptococci, Candida, pinworm infestation, and vaginal foreign bodies can cause a vaginal discharge.

Figure 66-14 Urethral prolapse. (Courtesy Carol Berkowitz, MD.)

Penile swelling may occur with balanoposthitis, priapism (often secondary to sickle cell disease), paraphimosis, or an infestation with chiggers. Fissures and tags in the perianal area may result from trauma but also may be associated with constipation and inflammatory bowel disease. Group A beta-hemolytic streptococci can cause painful inflammation with erythema in the perianal area (Fig. 66-15). Affected children may be febrile and experience pain with defecation. Hemorrhoids are rare in children and are associated with conditions that lead to an elevation of intra-abdominal venous pressure, as occurs with cirrhosis of the liver.

References

1. Goldman, J, Salus, MK, Wolcott, D, Kennedy, KY, A Coordinated Response to Child Abuse and Neglect: The Foundation for Practice. Child Abuse and Neglect User Manual Series. Washington, DC:U.S. Government Printing Office; 2003. www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/usermanuals/foundation/foundationc.cfm.

2. Roesler, TA, Jenny, C. Medical Child Abuse: Beyond Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008.

3. Kempe, CH, Silverman, FN, Steele, BF, Droegemueller, W, Silver, HK. The battered child syndrome. JAMA. 1962;181:17.

4. Woodling, BA, Kossoris, PD. Sexual misuse: Rape, molestation and incest. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1981;28:481.

5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Child Maltreatment 2009. Washington, DC:U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/stats_research/index.htm#can.

6. Wulczyn, F. Epidemiological perspectives on maltreatment prevention. Future Child. 2009;19:39.

7. Dubowitz, H, Bennett, S. Physical abuse and neglect of children. Lancet. 2007;369:1891.

8. Maguire, S, Mann, MK, Sibert, J, Kemp, A. Can you age bruises accurately in children? A systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:187.

9. Jenny, C, Reece, RM. Cutaneous manifestations of child abuse. In: Reece RM, Christian CW, eds. Child Abuse: Medical Diagnosis and Management. 3rd ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:19–51.

10. Kellogg, N. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect: Oral and dental aspects of child abuse and neglect. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1565.

11. Swerdlin, A, Berkowitz, C, Craft, N. Cutaneous signs of child abuse. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:371.

12. Kos, L, Shwayder, T. Cutaneous manifestations of child abuse. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:311.

13. Maguire, S, Moynihan, S, Mann, M, Potokar, T, Kemp, AM. A systematic review of the features that indicate intentional scalds in children. Burns. 2008;34:1072.

14. Thompson, S. Fractures, sprains, and dislocations. In: Osborn LM, DeWitt TG, First LR, Zenel JA, eds. Pediatrics. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby, 2005.

15. Kemp, AM, et al. Patterns of skeletal fractures in child abuse: Systematic review. BMJ. 2008;337:a1518.

16. Bulloch, B, et al. Cause and clinical characteristics of rib fractures in infants. Pediatrics. 2000;105:e48.

17. Maguire, S, et al. Does cardiopulmonary resuscitation cause rib fractures in children? A systematic review. Child Abuse Negl. 2006;30:739.

18. Hymel, KP, Makoroff, KL, Laskey, AL, Conaway, MR, Blackman, JA. Mechanisms, clinical presentations, injuries, and outcomes from inflicted versus noninflicted head trauma during infancy: Results of a prospective, multicentered, comparative study. Pediatrics. 2007;119:922.

19. Chiesa, A, Duhaime, AC. Abusive head trauma. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:317.

20. Adamsbaum, C, Grabar, S, Mejean, N, Rey-Salmon, C. Abusive head trauma: Judicial admissions highlight violent and repetitive shaking. Pediatrics. 2010;126:546–555.

21. Gerber, P, Coffman, K. Nonaccidental head trauma in infants. Childs Nerv Syst. 2007;23:499.

22. Case, ME. Inflicted traumatic brain injury in infants and young children. Brain Pathol. 2008;18:571.

23. Levin, A. Retinal hemorrhage in abuse head trauma. Pediatrics. 2010;126:961.

24. Pariset, JM, Feldman, KW, Paris, C. The pace and symptoms of blunt abdominal trauma to children. Clin Pediatr. 2010;49:24.

25. Trokel, M, DiScala, C, Terrin, NC, Sege, RD. Patient and injury characteristics in abusive abdominal injuries. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:700.

26. Finkel, MA. Sexual abuse: The medical examination. In: Giardino AP, Alexander R, eds. Child Maltreatment. 3rd ed. St Louis: GW Medical Publishing; 2005:253–288.

27. Jenny, C, Hymel, KP, Ritzen, A, Reinert, SE, Hay, TC. Analysis of missed cases of abusive head trauma. JAMA. 1999;281:621.

28. Chadwick, DL, et al. Annual risk of death resulting from short falls among young children: Less than 1 in 1 million. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1213–1224.

29. Barnes, PM, et al. Abdominal injury due to child abuse. Lancet. 2005;366:234.

30. Adams, JA, et al. Guidelines for medical care of children who may have been sexually abused. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2007;20:163.

31. Eppich, WJ, Zonfrillo, MR. Emergency department evaluation and management of blunt abdominal trauma. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19:265.

32. Hartley, LM, Khwaja, OS, Verity, CM. Glutaric aciduria type 1 and nonaccidental head injury. Pediatrics. 2001;107:174.

33. Workowski, KA, Berman, S, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1.

34. Halsey, MF, et al. Toddler’s fracture: Presumptive diagnosis and treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:152.

35. Mitchell, SM, et al. High frequencies of elevated alkaline phosphatase activity and rickets exist in extremely low birth weight infants despite current nutritional support. BMC Pediatr. 2009;29:9.

36. Byers, PH, Krakow, D, Nunes, ME, Pepin, M. Genetic evaluation of suspected osteogenesis imperfecta. Genet Med. 2006;8:383.