chapter 55 Child health and development

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

Infancy and childhood are characterised by a range of issues that broadly fall into three categories (Box 55.1):

SCREENING

Developmental assessments should include hearing, vision (including strabismus), language acquisition, fine motor skills, social skills and family dynamics. Enquiries need to be made about physical activity, nutrition, time spent watching television, accident prevention and sun protection.1 Given their high incidence, screen for iron deficiency and vitamin D deficiency in at-risk groups.

Children have tended to be the objects of healthcare; their opinions have frequently been ‘downgraded’ by healthcare professionals. Yet children also ‘acquire health-related knowledge through informal learning at home … they use their knowledge to promote their own well-being, in the context of and in interaction with social and physical features of their environment’.2 Children actively participate in the maintenance of healthy lifestyles (their own and others’). A child-to-child approach to health education (albeit with reference to older children) is in operation worldwide, and acknowledges children as active participants in health promotion and maintenance of healthy lifestyles.3

GROWTH MONITORING

ATOPY

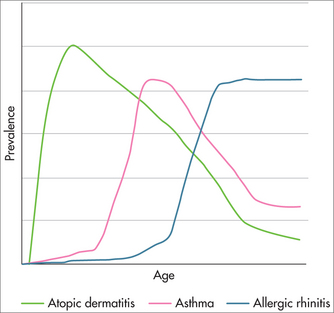

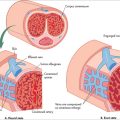

The prevalence of asthma and eczema among children (Fig 55.1) is increasing around the world.4 The notion of an ‘atopic march’ from eczema through to rhinitis has been coined,5 implying that early intervention may reduce the prevalence of disease in later life.

In our striving for cleanliness there is increasing evidence that skin sensitisation to known environmental allergens provokes immune responses that lead to eczema and, later, asthma. Immune provocation in susceptible individuals appears to trigger a cascade of events aggravated by early antibiotic exposure that may lead to medium- and long-term atopy.6

ECZEMA

Forty-six per cent of children with eczema have used complementary medicines by the time of presentation to a dermatologist,7 usually driven by their parents’ sense that standard advice has failed. Adverse effects of eczema include symptoms of itching and soreness, which cause sleeplessness. Sleep deprivation leads to tiredness, mood changes and impaired psychosocial functioning of the child and family, particularly at school and work. At the more severe end of the spectrum, embarrassment, comments, teasing and bullying may cause social isolation and may lead to depression or school avoidance. The child’s lifestyle is often limited, particularly with respect to clothing, holidays, staying with friends, owning pets, dietary exclusions, swimming or the ability to play or do sports. Restriction of normal family life, difficulties with complicated treatment regimens and increased work in caring for a child with eczema lead to parental exhaustion and feelings of hopelessness, guilt, anger and depression.8

ASSESSMENT

TREATMENT

Diet

Chinese herbal medicine

Individualised concoctions of Chinese herbal teas have been shown to be efficacious in a small number of randomised controlled trials from one centre.9 In general there were about 10 plant extracts in each preparation and few side effects were noted. In other trials there was no clear benefit. However, there have been reports of hepatic and nephro-toxicity, and hypersensitivity reactions.

Essential fatty acids

Patients with atopic dermatitis are thought to have a reduced rate of conversion from linoleic acid to gamma-linolenic acid (GLA), dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid, or arachidonic acid, compared with healthy subjects. Replacement of GLA, in the form of primrose oil or borage oil, may therefore benefit some patients. There are many randomised controlled studies assessing the effects of GLA, with most studies indicating an improved epidermal barrier on GLA application and others showing no effect, depending on the vehicle used for application.10,11 Note that, in the latter study, evening primrose oil proved to have a stabilising effect on the stratum corneum barrier, but this was apparent only with the water-in-oil emulsion, not the amphiphilic emulsion for topical use. Oral evening primrose oil capsules do not, however, have a useful effect.

PREVENTION AND EDUCATION

Supplementation with the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus has been found to substantially reduce the cumulative prevalence of eczema, but not atopy, by 2 years in susceptible individuals with a family history of eczema when given to the mother during pregnancy and for 6 months after birth.18 Other probiotics are less effective and the choice of Lactobacillus in this context seems to be important.18

Recent recommendations delay introduction of dairy products, eggs, nuts, fish and shellfish up to 36 months19,20 in high-risk situations but not for infants with no family history. However, there is a contrary view that suggests that early antigen exposure in small amounts, in an immune tolerance exercise, might prevent disease later.21

ALLERGIC RHINITIS

There is often a history of allergy in the child (infantile eczema) or the family.

TREATMENT

ASTHMA

(See also Ch 41, Respiratory medicine.)

Between 100 and 150 million people around the globe suffer from asthma, and this number is rising. Worldwide, deaths from this condition have reached over 180,000 annually.22

DIAGNOSIS

Children aged over 6 years can have spirometry testing.

Allergy testing should be organised.

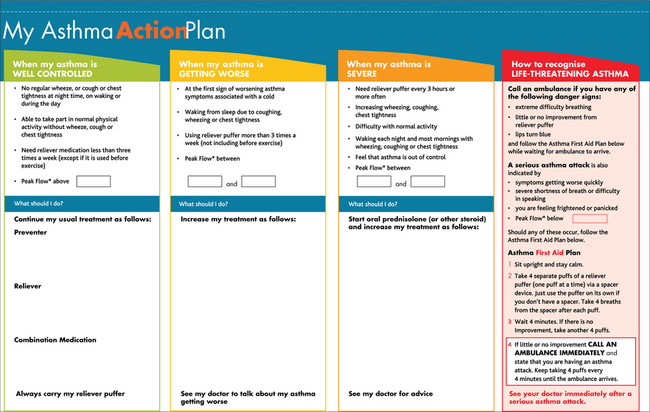

All children diagnosed with asthma will need an asthma management plan carefully developed with the child and their parents or carers, and conveyed to all carers and schools. The asthma action plan (Fig 55.2) chosen should be appropriate for the person’s age, educational status, language and culture.

PROPHYLAXIS

SUPPLEMENTATION

Dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids, zinc and vitamin C has been shown to significantly improve asthma control, pulmonary function tests and pulmonary inflammatory markers in children with moderately persistent bronchial asthma, either singly or in combination.24 Similarly, adequate intake of vitamin D and sun exposure are important in reducing the risk of asthma.

MANAGING ACUTE ASTHMA ATTACKS IN A CHILD

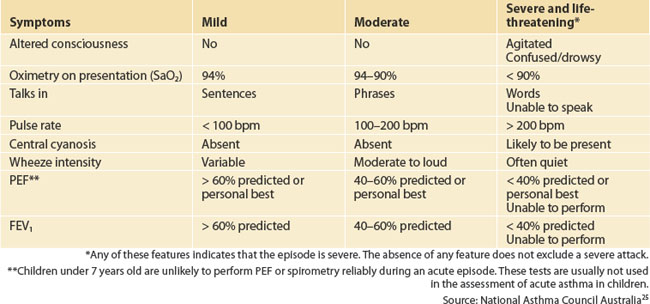

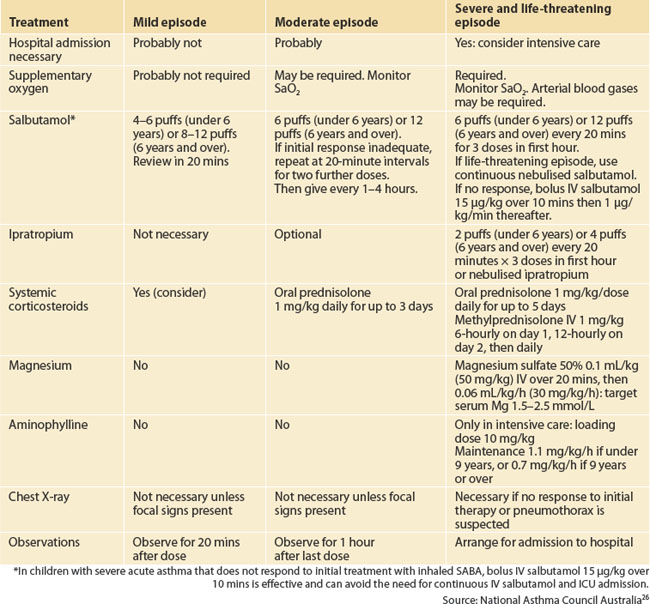

Beta2 agonist inhalers (salbutamol) and a spacer device should be available to the child at all times. Assessment and initial management of a child with acute asthma are summarised in Tables 55.1 and 55.2.

ANAPHYLAXIS IN CHILDREN

Anaphylaxis may occur as an acute allergic response to food allergens, medication, envenomation, vaccines, food additives and others.27 In some cases the causative agent is not identified.

Treatment

Whether in or out of hospital, help is called immediately and treatment initiated while awaiting advanced equipment and expertise. As soon as the clinical signs support the diagnosis of anaphylaxis, intramuscular adrenaline should be administered immediately while awaiting advanced equipment and expertise before an ambulance arrives.28

Bronchospasm should be treated as per the emergency management of severe asthma.

IRON DEFICIENCY

It is recognised that iron deficiency is associated with a range of developmental and behavioural problems in infancy and childhood that are reversible with iron supplementation and correction of the iron deficiency. Intellectual deficits arising from iron deficiency in infancy do persist into later years, if treatment is delayed. A high degree of suspicion is useful in infancy, as anaemia is a late manifestation of iron deficiency. Risk factors include prolonged breastfeeding without supplementation, more than six breastfeeds per day after 6 months, high cow’s milk intake after 12 months and poor solid intake because of high milk intake. Primary prevention of iron deficiency in infants and toddlers can be addressed by a range of measures (Box 55.2), and screening after 12 months is reasonable, particularly in high-risk groups. While prolonged breast feeding is beneficial, without an appropriate solid intake after 6–12 months iron deficiency is much more likely, and so care is required in advising about nutritional supplementation. Some infants become more iron deficient than others, probably because of feeding practices after birth but also because of the degree of intrauterine iron accumulation in the last trimester before birth. Preterm birth and intrauterine growth restriction interrupt normal iron stores and therefore are likely to lead to frank deficiency later if not addressed earlier.

SCREENING FOR HEARING LOSS

Universal Neonatal Hearing Screening (UNHS) is now well established in Australia, the United States and Europe. There are slight variations in protocols between states, but overall most use a system of automated auditory brain stem evoked responses (AABAER) using commercial screening apparatus. UNHS detects congenital sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) and ensures that babies are enrolled in a diagnostic pathway leading to early hearing aids or cochlear implantation in a timeframe that ensures language acquisition. Cochlear implantation produces best results when intervention occurs before 6 months. It is essential that babies identified in this way are fast-tracked into hearing services and ENT consultation, and engaged in early signing to ensure meaningful communication. While babies with obvious congenital abnormalities, preterm babies and babies admitted to a neonatal intensive care units can be readily identified as being at high risk of hearing impairment, between 1 and 3 per 1000 live births of otherwise normal babies are congenitally deaf. The results of early intervention programs and cochlear implantation are gratifying16 and allow these children to move seamlessly into normal schools, achieving normal social and educational skills.

The development of a robust neonatal hearing screening service broadly eliminates the utility of distraction testing during the first year of life.29 The latter is usually poorly performed in less than ideal settings and has poor sensitivity. Allaying parental concerns about hearing should not be attempted by using this as a screening test.

SCREENING FOR EYE AND VISION PROBLEMS

Amblyopia is a form of cerebral visual impairment caused by abnormal vision, commonly uncorrected refractive error, during a sensitive period of development. Treatment is thought to be effective only during this sensitive period, which varies for different types of amblyopia but most commonly lasts until 7 years of age. The most common forms of amblyopia are monocular, due to squint (strabismic amblyopia), or refractive error, with a prevalence of 2–4%. Such impairment is later a bar to certain occupations, affects binocular vision and stereopsis and causes considerable disability if the normal eye suffers trauma or disease.30 While definite disabilities caused by vision defects in childhood are largely unknown, more recent attention has focused on the possibility that vision problems contribute to behavioural problems or dyslexia (see below).

Intervention in children with strabismus is controversial. Treatment in those with considerably reduced acuity (6/18 and worse) can result in a mean acuity equivalent to 6/9 on the Snellen chart, whereas children with 6/9 or 6/12 show little benefit from treatment.30 Children whose treatment is deferred from age 4 until age 5 years have the same acuity after treatment, but fewer need patching treatment at all. More than a third of children thought to require treatment after repeat screening do not have acuity loss.31 Therefore screening is important, and inspection of the eyes in preschool children is useful in detecting squint likely to lead to impairment later. A careful corneal reflection test, cover test and prism test as well as eye movement tests will delineate abnormalities. In children with a family history of squint, children with developmental delays and preterm infants are at particular risk and may need referral to a specialist optometrist or paediatric ophthalmologist.

INFANTILE COLIC

Infantile colic is a condition in which a baby cries constantly at about the same time each day (usually in the evenings) and is very difficult to settle but otherwise healthy. The baby appears to be in pain and may pull their legs up and clench their fists. There may be loud bowel sounds. It usually begins in the first weeks of life, and goes away by 4–5 months of age.32

About one in five babies develops colic; it is more common in boys and in firstborn children. Breastfed infants have similar rates of colic as formula-fed infants. The cause is not known.

ENURESIS

Nocturnal enuresis can be considered normal up to the age of 5 years. It occurs in up to 20% of 5-year-olds and 10% of 10-year-olds, with a spontaneous remission rate of 14% per year. Weekly daytime wetting occurs in 5% of children, most (80%) of whom also wet the bed.33

INVESTIGATION

MANAGEMENT

In secondary enuresis management is to treat the underlying cause, and the enuresis tends to cease.

DYSLEXIA

Children whose reading is behind for their expected IQ, and who have symptoms of incoordination, poor sequencing and left-to-right confusion, are termed dyslexic. The problem affects 5–10% of children (mainly boys), who may present as depressed or develop compensatory behavioural symptoms that cause them to be labelled as lazy, ‘difficult’, defiant, ‘stupid’ or inattentive. Many more children than are diagnosed have dyslexia problems and few receive appropriate interventions in remediation. Inability to recognise the meaning of written words or to interpret unfamiliar words has physiological and anatomical correlates that can readily be identified and mapped to abnormalities in chromosome 6 and others. Recent insights have enabled the development of interventions that will attenuate symptoms and facilitate the child’s progress in a mainstream educational environment. The more recent concept of visual stress (Box 55.3) can explain a number of behaviours that are seen in children with degrees of dyslexia.

Dyslexic children identified as having high visual stress showed significantly higher percentage increases in reading rate with a coloured overlay, and reported significantly higher critical symptoms of visual stress compared to dyslexic children with low visual stress.34 Thus, while phonological deficits underlie most issues for children with dyslexia, aids to visual interpretation such as coloured overlays or tinted lenses may make a significant difference in about 50%.35 The other important development is in the arena of fatty acid supplementation. It is increasingly obvious that the diets of today’s children are markedly different from those of previous generations. The epidemic of obesity (see below) is serious and coincides with more attention deficit disorders and dyslexia than before. There is mounting evidence that essential fatty acid deficiency may contribute to neurodevelopmental and psychiatric problems including dyslexia, and that supplementation may have significant and long-lasting benefit.36,37 However, care needs to be taken in delivering essential fatty acids that are likely to be effective. A combination of 80% fish oil and 20% evening primrose oil has been used in most studies.

DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDERS AND DISABILITIES

In considering child development disorders, Hall and Elliman38 distinguished between low-prevalence high-severity conditions (cerebral palsy, learning disabilities; see Box 55.4) for which a pathological basis can be identified, and high-prevalence low-severity conditions (speech delay, clumsiness; see Box 55.5) for which a pathological basis is rarely found.

BEHAVIOUR AND PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS

The point prevalence for psychological problems in childhood and adolescence is about 20%; it is worse in socially deprived areas. It has been estimated that 68% of preschool children have at least one identifiable problem, and close to one-third have three or more problems. Indeed, such problems characterise 50% of referrals to a paediatrician.39

Point prevalences for a range of conditions are shown in Table 55.3.

TABLE 55.3 Point prevalence of a range of childhood conditions

| Condition | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Preschool children (< 5 years) | |

| Waking and crying | 15 |

| Overactivity | 13 |

| Difficulty settling at night | 12 |

| Refusal of food | 12 |

| Combination behavioural problems | 10 |

| Middle childhood (6–12 years) | |

| Persistent tearful unhappy moods | 12 |

| Bedtime behavioural rituals | 8 |

| Night terrors and sleep disturbance | 6 |

| Bedwetting | 5 |

| Inattentive overactivity | 5 |

| Faecal soiling | 1 |

| Overt psychological disorder | 12–25 |

| Overt handicapping psychiatric disorder | 7–14 |

| Mild emotional behavioural problems* | 5–11 |

| Adolescence (13–18 years) | |

| Appreciable misery | 45 |

| Social sensitivity | 30 |

| Evident anxiety | 25 |

| Suicidal ideation | 7 |

| Complex depressive moods | 10 |

| Confirmed psychiatric disorder | 2–3 |

* Including anxious unhappiness, difficult or antisocial behaviour, poor relationships with other children.

Source: adapted from Hall & Elliman 200638

While some of these might be considered minor or mild, they are the source of considerable misery and reflect a poor quality of existence for many parents and children in our community.39 These problems interact with physical ill health and produce symptoms that span organic and psychological illness. They are characteristically persistent and polymorphous even though they may have started as discrete single problems.

ATTENTION DEFICIT HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER

The diagnosis of ADHD is complex and reflects the difficulty of separating comorbidities that may in fact be the primary problem leading to behavioural and educational issues that need addressing. How, then, can the GP intervene and muster allied healthcare services and family support before referring to a paediatrician for consideration of more aggressive pharmacological intervention? There is no doubt that psychostimulant medication is efficacious in the short term in attenuating the symptoms of ADHD in children with uncontrollable or dangerous behaviour. In the long term, children with diagnosed ADHD, whether treated or not, have worse outcomes than those not diagnosed with ADHD. Treatment effect is short term and may allow children to function at home or at school more effectively, reducing stress on affected children and their families and improving social behaviour. However, the long-term results are not positive. The West Australian Raine study41 found that, by age 14 years, stimulant medication did not significantly improve a child’s level of depression, self-perception or social functioning, and that these children were more likely to be performing below their age level at school by a factor of 10.5 times compared with children who had not taken stimulant medication.

INITIAL ASSESSMENT

AUTISM AND AUTISM-SPECTRUM DISORDERS

Parents often express concern about their child’s development and can identify behaviours that are worrying. These should never be dismissed and careful review may inform appropriate referral. The checklist for autism in toddlers (CHAT) (see Table 55.4) can be used to screen for likely ASD traits.

| A screening test designed to be used in children from 18 months to 36 months. Darker-shaded response boxes indicate critical questions most indicative of autistic characteristics. |

| CHAT Section A: Questions for parents | |

|---|---|

| Yes or No | |

| Does your child enjoy being swung, bounced on your knee, etc.? | |

| Does your child take an interest in other children? | |

| Does your child like climbing on things, such as chairs? | |

| Does your child enjoy playing peek-a-boo/hide & seek? | |

| Does your child ever pretend, for example, to make a cup of tea using a toy cup and teapot, or pretend other things (pouring juice)? [Pretend Play (PP)] | |

| Does your child ever use his or her index finger to point, to ask for something? | |

| Does your child ever use his or her index finger to point, to indicate interest in something? [Protodeclarative Pointing (PDP)] | |

| Can your child play properly with small toys (e.g. cars or blocks) without just mouthing, fiddling or dropping them? | |

| Does your child ever bring objects to you (parent), to show you something? | |

| Shaded boxes indicate critical questions most indicative of autistic characteristics | |

| CHAT Section B: Physician’s questions/observations | |

|---|---|

| Yes or No | |

Overall, the more ‘NOs’ the higher the chance of autism.

In the Baron Cohen studies:

Failing all questions with shaded boxes: risk of autism 80–85%.

Passing all questions with shaded boxes: risk of autism 0%.

Sources: Baron Cohen S et al. 199245, 200046; Baird et al. 200047

OBESITY

The epidemic of childhood obesity in the developed world cannot be ignored. Obesity rates for preschool children have doubled internationally, and rates for children aged 6–11 years have tripled since 1996. Overweight adolescents have a 70% chance of becoming obese adults, increasing to 80% where one or more parent is also obese or overweight. Sixty per cent of obese children have one or more additional cardiovascular risk factors (high cholesterol, triglycerides, insulin or blood pressure) identifiable at screening. Serious complications of obesity (type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, fatty liver, slipped epiphyses, hypertension, polycystic ovarian syndrome etc) can be identified in many (Box 55.6).

Body mass index (BMI) is a robust predictor of continuing risk from overweight and obesity into adolescence. Children noted to be overweight at 24, 36 or 54 months are five times more likely to be obese in adolescence than children with normal BMI during infancy.48 The formula for calculating body mass index (BMI) between 2 and 20 years is shown in Box 55.7. A useful BMI calculator with downloadable BMI curves for children can be found at the Melbourne Royal Children’s Hospital website (see Resources list). BMI categories are listed in Table 55.5.

| Category | BMI |

|---|---|

| Underweight | < 5th percentile for age and gender |

| Normal weight | ≥ 5th percentile to < 85th percentile for age and gender |

| At risk of overweight | 85th percentile to < 95th percentile for age and gender |

| Overweight | 95th percentile for age and gender |

The causes of overweight and obesity are multifactorial (genetic predisposition, overeating, sedentary lifestyle, excessive screen time, fast-food availability, poor overall nutrition, inadequate nutrition knowledge, family role-modelling, school and home environments, food marketing and advertising). The goals of preventing and reversing obesity and overweight appear straightforward—reduce energy intake while maintaining an optimal nutritional intake to support growth and development. Reduce sedentary behaviours, actively engage families, parents, carers and communities in strategies to enhance and apply knowledge and understanding of optimal nutrition during childhood.49

Assessment and intervention begins as follows:

TABLE 55.6 Factors associated with readiness for change and engagement

| Factor | Family response | Physician response |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-contemplation | Not interested | Deliver information about known health risks. Personalise to examination and assessment |

| Contemplation | Interested in the next 6 months or so | Deliver messages of health risk and identify barriers to change and engagement |

| Preparation | Willing to try out and plan over the next month | Assist children and family to set reasonable goals—start with one or two easy targets. |

| Action | Already trying to lose weight | Give positive reinforcement and set new targets |

| Maintenance | Successful weight management needs help in maintenance | Provide support and monitoring |

NUTRITION AND INTEGRATIVE MEDICINE

EXERCISE AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

Physical activity is essential in long-term maintenance of weight control in children, and interventions aimed at either increasing physical activity or decreasing physical inactivity or sedentary behaviours) are useful in treating paediatric obesity.53 There is definitive evidence that obesity is an inflammatory condition characterised by elevated inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein, and that these inflammatory markers diminish with any exercise.54

The structure of an exercise program is also important for developing an active lifestyle in treating obesity. Data from several trials incorporating moderate to intense aerobic exercise suggest that school-based exercise interventions may be a promising approach to treating childhood obesity.55,56 In addition, the family is important to structure and support activity, as parental activity level is a strong predictor of child activity.57,58 In the healthcare setting, interventions focused on increasing physical activity should be delivered in a nurturing, non-intimidating environment. Obese children respond differently physiologically and emotionally to exercise than do normal-weight children, and experience negative consequences to participation in activities considered appropriate for normal-weight children. In clinical settings, specialised exercise programs that include specific recommendations for obese children have been shown to enhance safety, efficacy and compliance during treatment. Optimal results may be achieved by combining programs to reduce sedentary behaviours with those that increase physical activity,59 such as walking or cycling to school instead of travelling by car.

A healthcare plan for the treatment of childhood obesity should examine and modify, as necessary, the home environment as it pertains to physical activity. Some children spend more time in front of the television and playing video games than doing any other activity other than sleeping. Watching television often decreases the amount of time spent performing physical activities, and is also associated with increased food consumption either during viewing or as a result of food advertisements.60 Children who watched 4 or more hours of television per day had significantly greater BMI than those watching less than 2 hours per day.61 Furthermore, having a television in the bedroom has been reported to be a strong predictor of being overweight, even in preschool-aged children.62 Note that fatness leads to inactivity, rather than inactivity leading to fatness,63 but inactivity reduces fitness and increases cardiovascular inflammatory risk, whether fat or thin.

A practical approach to encouraging exercise in children has been outlined by Philpott and colleagues.64 The easiest way to promote physical activity is to increase movement in daily life. If possible, children should walk or cycle to school, and use stairs instead of lifts. Children allowed to play outdoors usually increase their level of activity spontaneously. Increase participation in household chores from an early age. Involve children in meal preparation and clearing up, thereby reducing potential screen time while increasing responsibility and accountability. Moderate to vigorous activity for 60 minutes each day is the goal that produces the best effect, even if broken down into four 15-minute periods. Plan family activities and use the outdoors. Make practical recommendations for exercise. A written prescription will help to focus goals and stimulate discussion at subsequent visits.

Understand motivational interviewing and use tools for ensuring engagement by children and their families. Individualise the activities to suit the personality of each child—consider their like and dislikes. Consider age-appropriate interventions and recognise particular goals of older children, whether muscle building, endurance or fast exercise. Encourage dance in all its current forms and, if necessary, use interactive video games that encourage movement. There is no single ‘one-fits-all’ solution. Being aware of family dynamics and personal relationships is also important. Engage all the family together, rather than targeting individuals alone.

IMMUNISATION

Specific details of national immunisation programs differ between countries. An indicative schedule for children aged 0–4 years in Australia54 is given in Table 55.7.

TABLE 55.7 Immunisation schedule for children up to 4 years old (Australia)

| Age | Disease immunised against |

|---|---|

| Birth | Hepatitis B |

| 2 months |

Source: Australian Government65

Infant hearing program Utah, USA. http://www.infanthearing.org/.

NHS UK. http://hearing.screening.nhs.uk/.

Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne. http://www.rch.org.au/ccch/research/infanthearing/index.cfm?doc_id=713.

1 Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Red book. Melbourne: RACGP. Online. Available: http://www.racgp.org.au/redbook/download/2009Redbook_7th_ed_chart_children.pdf.

2 Mayall B. Children, health and the social order. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press, 1996.

3 Pridmore P, Stephens D. Children as partners for health: a critical review of the child-to-child approach. London: Zed Books, 2000.

4 Innes Asher M, Montefort S, Björkstén B, et althe ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006;368:733-743.

5 Spergel JM, Paller AS. Atopic dermatitis and the atopic march. J Allergy Clin Immun. 2003;112(6 Suppl 1):S118-S127.

6 Kummeling I, Stelma FF, Dagnelie PC, et al. Early life exposure to antibiotics and the subsequent development of eczema, wheeze, and allergic sensitization in the first 2 years of life: the KOALA Birth Cohort Study. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):e225-e231.

7 Johnston GA, Bilbao RM, Graham-Brown RAC. The use of complementary medicine in children with atopic dermatitis in secondary care in Leicester. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(3):566-571.

8 Lewis-Jones S. Quality of life and childhood atopic dermatitis: the misery of living with childhood eczema. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(8):984-992.

9 Sheehan M, Atherton D. A control trial of traditional Chinese herbal medicinal plants in widespread non-exudative eczema. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:179-184.

10 Levin C, Maibach H. Exploration of ‘alternative’ and ‘natural’ drugs in dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(2):207-211.

11 Gehring W, Bopp R, Rippke F, et al. Effect of topically applied evening primrose oil on epidermal barrier function in atopic dermatitis as a function of vehicle. Arzneimittelforschung. 1999;49(7):635-642.

12 Furuhjelm C, Warstedt K, Larsson J, et al. Fish oil supplementation in pregnancy and lactation may decrease the risk of infant allergy. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98(9):1461-1467.

13 Rautava S, Kalliomäki M, Isolauri E. Probiotics during pregnancy and breast-feeding might confer immunomodulatory protection against atopic disease in the infant. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:119-121.

14 Kalliomäki M, Salminen S, Poussa T, et al. Probiotics and prevention of atopic disease: 4-year follow-up of a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9372):1869-1871.

15 Miyake Y, Sasaki S, Tanaka K, et al. Consumption of vegetables, fruit, and antioxidants during pregnancy and wheeze and eczema in infants. Allergy. 2010; 22 Jan. [Epub ahead of print]

16 Snijders BEP, Thijs C, Kummeling I, et al. Breastfeeding and infant eczema in the first year of life in the KOALA birth cohort study: a risk period-specific analysis. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):e137-e141.

17 Ludvigsson JF, Mostrom M, Ludvigsson J, et al. Exclusive breastfeeding and risk of atopic dermatitis in some 8300 infants. Pediatr Allery Immunol. 2005;16(3):201-208.

18 Probiotic Study Group. Wickens K, Black PN, Stanley TV et al. A differential effect of two probiotics in the prevention of eczema and atopy: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(4):788-794.

19 Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2):346-349.

20 Fiocchi A, Assa’ad A, Bahna S. Food allergy and the introduction of solid foods to infants: a consensus document. Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee, American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(1):10-20.

21 Niggemann B, Staden U, Rolinck-Werninghaus C, et al. Specific oral tolerance induction in food allergy. Allergy. 2006;61(7):808-811.

22 World Health Organization. Bronchial asthma. Fact Sheet 206. Online. Available: https://apps.who.int/inf-fs/en/fact206.html, January 2000.

23 Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing. My asthma management plan; 2006. Online. Available: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/957D057CE967D0FECA256F1900136C63/$File/Action%20plan%20form%20page%2020%20Feb%202009.pdf.

24 Biltagi MA, Baset AA, Bassiouny M. Omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin C and zinc supplementation in asthmatic children: a randomized self-controlled study. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98(4):737-742.

25 National Asthma Council Australia. Acute asthma. Managing children. Initial assessment. Online. Available: http://www.nationalasthma.org.au/cms/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=203&Itemid=151.

26 National Asthma Council Australia. Acute asthma. Managing children. Management. Online. Available: http://www.nationalasthma.org.au/cms/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=94&Itemid=103. last updated 31 May 2007.

27 Novembre E, Cianferroni A, Bernardini R, et al. Anaphylaxis in Children: Clinical and Allergologic Features. Pediatrics. 101, 1998. 8-DOI : 10.1542/peds.101.4.e8

28 Tse Y, Rylance G. Emergency management of anaphylaxis in children and young people: new guidance from the Resuscitation Council (UK). Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2009;94:97-101.

29 Russ SA, Poulakis Z, Wake M, et al. The distraction test: the last word? J Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41(4):197-200.

30 Clarke MP, Wright CM, Hrisos S, et al. Randomised controlled trial of treatment of unilateral visual impairment detected at preschool vision screening. BMJ. 2003;327(7426):1251-1254.

31 Williams C, Northstone K, Harrad RA, et al. Amblyopia treatment outcomes after screening before or at age 3 years: follow up from randomised trial. BMJ. 2002;324(7353):1549-1551.

32 Lucassen PL. Effectiveness of treatments for infantile colic: systematic review. BMJ. 1998;316(7144):1563-1569.

33 Caldwell PH, Edgar D. Bedwetting and toileting problems in children. Med J Aust. 2005;182(4):190-195.

34 Singleton, Henderson L-M. Computerized screening for visual stress in children with dyslexia. Dyslexia. 2007;13(2):130-151.

35 Whiteley H, Smith C. The use of tinted lenses to alleviate reading difficulties. J Res Reading. 2001;24(1):30-40.

36 Joshi K, Lad S, Kale M, et al. Supplementation with flax oil and vitamin C improves the outcome of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Prostaglandins, Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2006;74(1):17-21.

37 Richardson AJ, Montgomery P. The Oxford-Durham Study: a randomised, controlled trial of dietary supplementation with fatty acids in children with developmental coordination disorder. Pediatrics. 2005;115(5):1360-1366.

38 Hall D, Elliman D. Health for all children. Rev. edn. Oxford: OUP, 2006.

39 Hewson PH, Anderson PK, Dinning AH, et al. A 12-month profile of community paediatric consultations in the Barwon region. J Paediatr Child Health. 1999;35(1):16-22.

40 Greenhill LL, Pliszka S, Dulcan MK, et al. Practice parameter for the use of stimulant medications in the treatment of children, adolescents, and adults. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(2 Suppl):26S-49S.

41 Government of Western Australia, Department of Health. Raine ADHD Study: long-term outcomes associated with stimulant medication in the treatment of ADHD in children. Online. Available: http://www.health.wa.gov.au/publications/documents/MICADHD_Raine_ADHD_Study_report_022010.pdf.

42 Kozielec T, Starobrat-Hermelin B. Assessment of magnesium levels in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Magnes Res. 1997;10(2):143-148.

43 Starobrat-Hermelin B, Kozielec T. The effects of magnesium physiological supplementation on hyperactivity in children with attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD): positive response to magnesium oral loading test. Magnes Res. 1997;10(2):149-156.

44 Johnson M, Ostlund S, Fransson G, et al. Omega-3/omega-6 fatty acids for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial in children and adolescents. J Atten Disord. 2009;12(5):394-401.

45 Baron-Cohen S, Allen J, Gillberg C. Can autism be detected at 18 months? The needle, the haystack and the CHAT. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;161:839-843.

46 Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Cox A, et al. Early identification of autism by the CHecklist for Autism in Toddlers (CHAT). J R Soc Med. 2000;93:521-525.

47 Baird G, Charman T, Baron-Cohen S, et al. A screening instrument for autism at 18 months of age: a 6-year follow-up study. Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:694-702.

48 Nader PR, O’Brien M, Houts R, et al. Identifying risk for obesity in early childhood. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):e594-e601.

49 Kirk S, Scott BJ, Daniels SR. Pediatric obesity epidemic: treatment options. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(5 Suppl 1):44-51.

50 Rakel D. Integrative medicine. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2007.

51 Resnicow K, Davis R, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing for pediatric obesity: conceptual issues and evidence review. J Amer Diet Assoc. 2006;106(12):2024-2033.

52 Schwartz RP. Motivational interviewing (patient-centred counseling) to address childhood obesity. Pediatr Ann. 2007;39:3. 154–158.

53 Krebs NF, Jacobson MS. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. Prevention of pediatric overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2003;112(2):424-430.

54 Farpour-Lambert NJ, Aggoun Y, Marchand LM, et al. Physical activity reduces systemic blood pressure and improves early markers of atherosclerosis in pre-pubertal obese children. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2396-2406.

55 Carrel AL, Clark RR, Peterson SE, et al. Improvement of fitness, body composition and insulin sensitivity in overweight children in a school-based exercise program. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(10):963-968.

56 Evans RK, Franco RL, Stern M, et al. Evaluation of a 6-month multi-disciplinary healthy weight management program targeting urban, overweight adolescents: Effects on physical fitness, physical activity, and blood lipid profiles. Int J Pediatr Obesity. 2009;4(3):130-133.

57 Cleland V, Venn A, Fryer J, et al. Parental esercise is associated with Australian children’s extracurricular sports participation and cardiorespiratory fitness. A cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2005;2(1):3.

58 Dowda M, Ainsworth BE, Addy CL, et al. Environmental influences, physical activity and weight status in 8–16 year olds. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:711-717.

59 Nemet D, Barkan S, Epstein Y, et al. Short- and long-term beneficial effects of a combined dietary-behavioural physical activity intenvention for the treatment of childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2005;115:443-449.

60 Giammattei J, Blix G, Marshak HH, et al. Television watching and soft drink consumption. Associations with obesity in 11–13 year old schoolchildren. Arch Pediatr Adol Med. 2003;157:882-886.

61 van Zutphen M, Bell AC, Kremer PJ, et al. Association between the family environment and television viewing in Australian children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007;43:458-463.

62 Dennison BA, Erb TA, Jenkins PL. Television viewing and television in bedroom associated with overweight risk among low income preschool children. Pediatrics. 2002;109:1028-1034.

63 Metcalf BS, Hosking J, Jeffery AN, et al. Fatness leads to inactivity, but inactivity does not lead to fatness: a longitudinal study in children (earlybird 45). Arch Dis Child. 2010. [epub before print doi.1136/adc2009.175927]

64 Philpott J, Wilson E, Luke A. The importance of exercise: know how to say ‘Go’. Pediatr Ann. 2010;39(3):162-171.

65 Australian Government, Medicare Australia. Current immunisation schedule. National Immunisation Program (NIP) Schedule (0–4 years) (from July 2007). Online. Available: http://www.medicareaustralia.gov.au/provider/patients/acir/schedule.jsp.