CHAPTER 54 Chest wall and breast

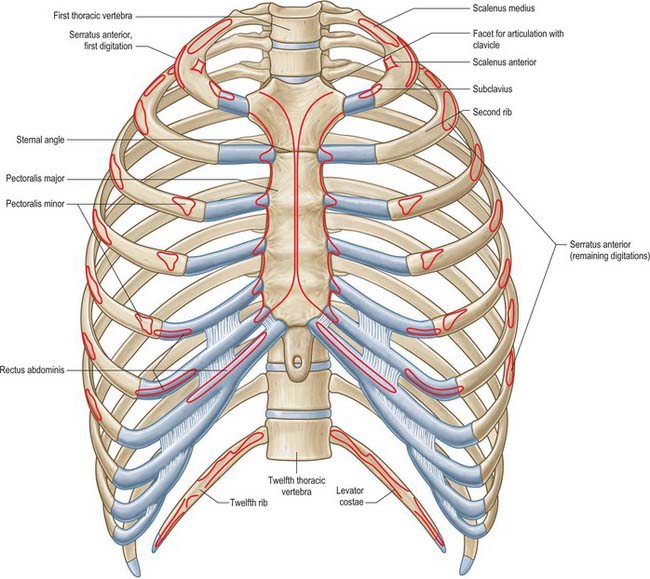

The chest wall surrounds the thoracic cavity. The skin and soft tissue cover a musculoskeletal frame consisting of 12 pairs of ribs which articulate with 12 thoracic vertebrae posteriorly, and (except for the last two pairs of ribs) with the sternum anteriorly, via their costal cartilages; intrinsic muscles and muscles which connect the chest wall with the upper limb and the vertebral column; numerous blood and lymphatic vessels and nerves which supply the components of the musculoskeletal frame and the overlying skin and breast tissue.

SKIN AND SOFT TISSUE

SKIN

Vascular supply

Arteries

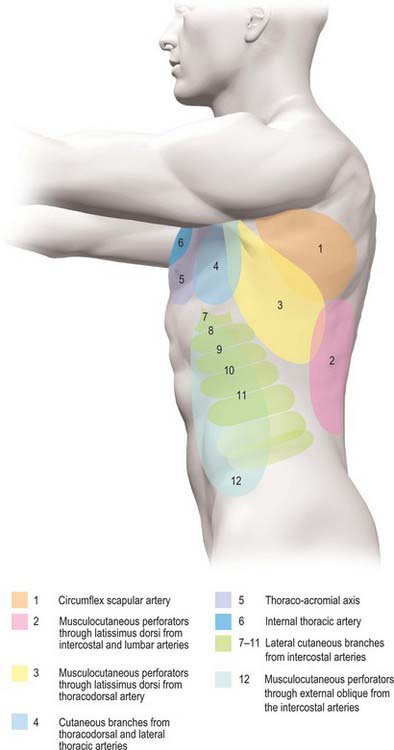

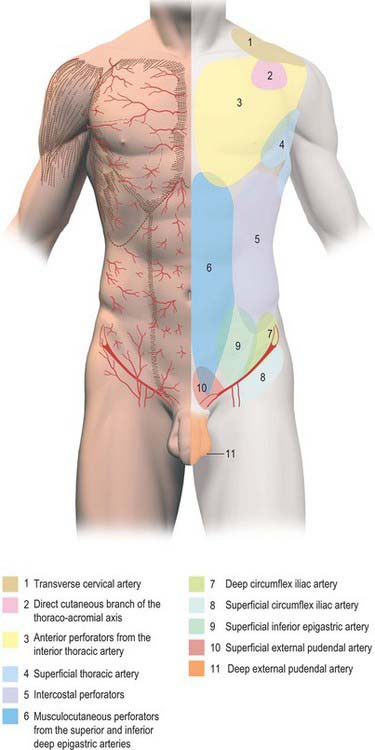

The skin of the thorax is supplied by a combination of direct cutaneous vessels and musculocutaneous perforators which reach the skin primarily via the intercostal muscles, pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi and trapezius. Branches from the thoracoacromial axis, lateral thoracic artery, internal thoracic artery, anterior and posterior intercostal arteries, thoracodorsal, transverse cervical/dorsal scapular and circumflex scapular arteries are the major contributing vessels (Figs 54.1, 54.2; see Fig. 42.4).

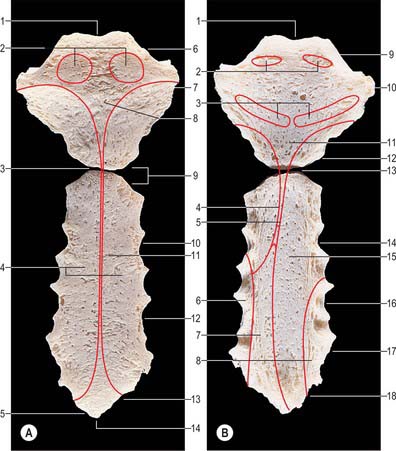

Fig. 54.1 Anatomical territories of cutaneous blood vessels on the anterior trunk.

(By permission from Cormack GC, Lamberty BGH 1994 The Arterial Anatomy of Skin Flaps, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.)

Veins

The intercostal veins accompany the similarly named arteries in the intercostal spaces (see Fig. 53.3). The small anterior intercostal veins are tributaries of the internal thoracic and musculophrenic veins; the internal thoracic veins drain into the appropriate brachiocephalic vein. The posterior intercostal veins drain backwards and most drain directly or indirectly into the azygos vein on the right and the hemiazygos or accessory hemiazygos veins on the left. The azygos veins exhibit great variation in their origin, course, tributaries, anastomoses and termination (see Ch. 55).

Lymphatic drainage

Superficial lymphatic vessels of the thoracic wall ramify subcutaneously and converge on the axillary nodes (see p. 928, Figs 54.19, 54.21). Lymph vessels from the deeper tissues of the thoracic walls drain mainly to the parasternal, intercostal and diaphragmatic lymphatic nodes.

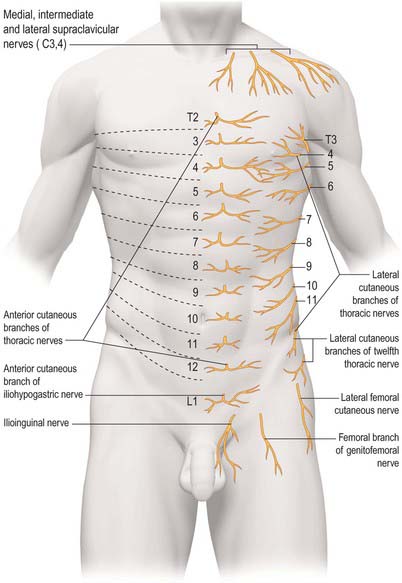

Innervation

The skin of the thorax is supplied by cutaneous branches of cervical and thoracic nerves in consecutive, curved zones, the upper almost horizontal and the lower oblique. On the upper ventral thoracic aspect, the third and fourth cervical areas adjoin the first and second thoracic areas (Fig. 54.3; see Fig. 42.3) because the intervening nerves provide the sensory and motor supply to the upper limb. There is a similar, but less extensive, posterior ‘gap’: most of the skin of the back of the thorax is supplied by the dorsal rami of the thoracic nerves. The subcostal margin is supplied by the seventh thoracic nerve.

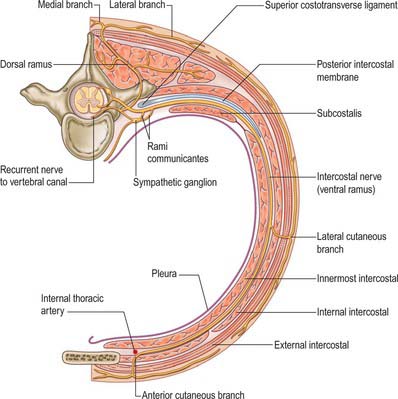

The ventral rami of the first to the eleventh thoracic nerves pass into the intercostal spaces. Each intercostal nerve gives off a lateral cutaneous branch, which arises beyond the angle of the ribs and divides into anterior and posterior branches, and terminates near the sternum in an anterior cutaneous branch (see Fig. 54.18).

Fig. 54.18 The course of a typical intercostal nerve. The muscular and the collateral branches are not shown.

Branches of the supraclavicular nerve, which originates from the third and fourth cervical nerve roots, supply the skin in the upper pectoral region. Most of the first thoracic nerve joins the brachial plexus: it gives off a small inferior branch, which becomes the first intercostal nerve. The lateral cutaneous branch of the second intercostal nerve supplies the skin of the axilla and is known as the intercostobrachial nerve. The costal margin is supplied by a branch from the seventh thoracic nerve, and the tenth thoracic nerve supplies the skin of the abdomen at the level of the umbilicus. The seventh to eleventh thoracic nerves supply the skin of the thoracic wall as they pass anteriorly and inferiorly; they continue beyond the costal cartilages and supply the skin and subcutaneous tissues of the abdominal wall. The subcostal nerve follows the inferior border of the twelfth rib and supplies the skin of the lower abdominal wall (Fig. 54.3).

BONE AND CARTILAGE

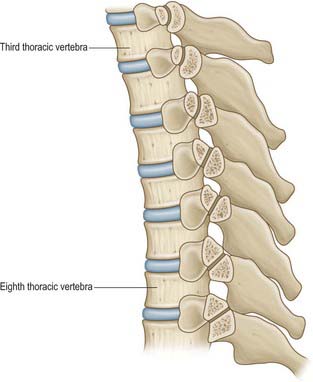

The 12 thoracic vertebrae and their associated intervertebral discs are described in detail in Chapter 42.

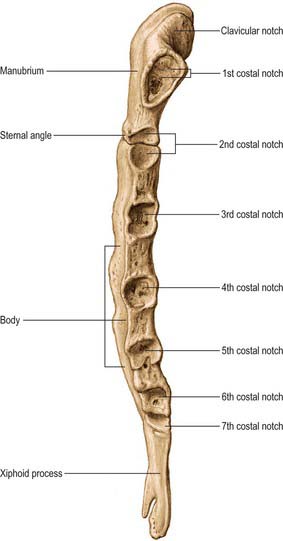

STERNUM

The sternum consists of a cranial manubrium, an intermediate body (mesosternum) and a caudal xiphoid process (Figs 54.4, 54.5). Until puberty, the mesosternum consists of four sternebrae, which, from their costal relations, appear to be intersegmental. The total length of the sternum is approximately 17 cm in males, less in females. The ratio between manubrial and mesosternal lengths differs between the sexes. Growth may continue beyond the third decade and possibly throughout life.

Body

The body is level with the fifth to ninth thoracic vertebrae. It is longer, narrower and thinner than the manubrium, and is broadest near its lower end. The anterior surface is nearly flat and faces slightly upwards. It bears three variable transverse ridges, which mark the levels of fusion of its four sternebrae. A sternal foramen, of varying size and form, may occur between the third and fourth sternebrae. The posterior surface, slightly concave, also displays three less distinct transverse lines. The oval upper end articulates with the manubrium at the level of the sternal angle (manubriosternal joint), which lies opposite the inferior border of the fourth vertebral body. The manubriosternal joint is marked by a posterior transverse groove and is palpable anteriorly as a ridge (Fig. 54.5).

The lower end of the body is narrow and continuous with the xiphoid process. On each lateral border, at its superior angle, a small notch articulates with part of the second costal cartilage (Fig. 54.4). Below this, four costal notches articulate with the third to sixth costal cartilages. The inferior angle bears a small facet which, together with the xiphoid process, articulates with the seventh costal cartilage. Between these articular depressions, a series of curved edges diminish in length downwards and form the anterior limits of the intercostal spaces.

Xiphoid process (xiphisternum)

The xiphoid process is in the epigastrium. It is the smallest and most variable sternal element, and may be broad and thin, pointed, bifid, perforated, curved or deflected. The xiphoid is cartilaginous in youth, but more or less ossified in adults. It is continuous with the lower end of the body at the xiphisternal joint. Anterior to its superolateral angles there are demifacets that articulate with parts of the seventh costal cartilages (Fig. 54.5).

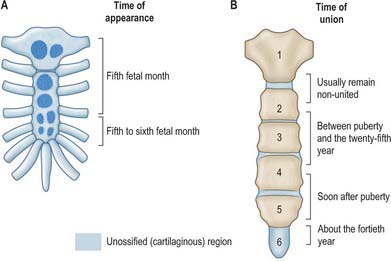

The sternum is formed by fusion of two cartilaginous sternal plates flanking the median plane. The arrangement and number of centres of ossification vary according to the level of completeness and time of fusion of the sternal plates, and to the width of the adult bone. Incomplete fusion leaves a sternal foramen. The manubrium is ossified from one to three centres appearing in the fifth fetal month. The first and second sternebrae usually ossify from single centres that appear at about the same time (Fig. 54.6A). Centres in the third and fourth sternebrae are commonly paired, and appear in the fifth and sixth months, respectively, but one of either pair may be delayed until the seventh or even eighth month, and the fourth sternebral centre may be absent. The xiphoid process begins to ossify in the third year or later. In some sterna, all centres are single and median; in others, the manubrial centre is single and the sternebral centres are all paired, symmetric or asymmetric. Union between mesosternal centres begins at puberty and proceeds from below upwards: by the age of 25 years, they are all united (Fig. 54.6B).

RIBS

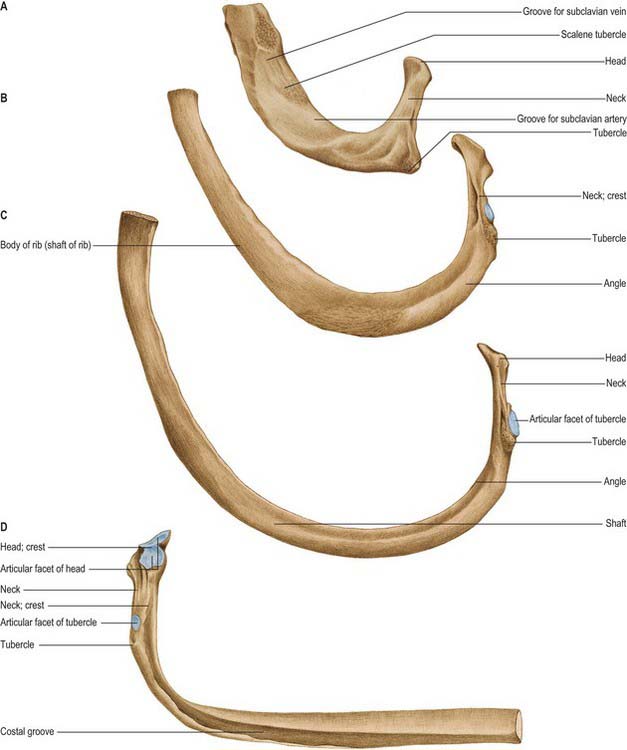

The ribs are 12 pairs of elastic arches (Fig. 54.7). They articulate posteriorly with the vertebral column and form the greater part of the thoracic skeleton. Their number may be increased by cervical or lumbar ribs or reduced by the absence of the twelfth pair. The first seven pairs are connected to the sternum by costal cartilages, and are referred to as the true ribs. The remaining five are the so-called false ribs: the cartilages of the eighth to tenth usually join the superjacent costal cartilage, whereas the eleventh and twelfth ribs, which are free at their anterior ends, are sometimes termed the ‘floating’ ribs. The tenth rib may also be a floating rib; the incidence varies from 35% to 70% in different races.

Typical rib

A typical rib has a shaft with anterior and posterior ends (Fig. 54.8). The anterior, costal, end has a small concave depression for the lateral end of its cartilage. The shaft has an external convexity and is grooved internally near its lower border, which is sharp, whereas its upper border is rounded. The posterior, vertebral, end has a head, neck and tubercle. The head presents two facets, separated by a transverse crest. The lower and larger facet articulates with the body of the corresponding vertebra, its crest attaching to the intervertebral disc above it. The neck is the flat part beyond the head, anterior to the corresponding transverse process. It is oblique, and faces anterosuperiorly. Its posteroinferior surface is rough and pierced by foramina. Its upper border is the sharp crest of the neck, its lower border rounded. The tubercle, which is more prominent in upper ribs, is posteroexternal at the junction of the neck and shaft and is divided into medial articular and lateral non-articular areas. The articular part bears a small, oval facet for the transverse process of the corresponding vertebra. The nonarticular area is roughened by ligaments. The shaft is thin and flat and has external and internal surfaces, and superior and inferior borders. It is curved, bent at the posterior angle (5–6 cm from the tubercle), and twisted about its long axis. The part behind the angle inclines superomedially, and so its external surface is posteroinferior. In front of the angle it faces slightly up. It is convex and smooth, and near the tubercle is crossed by a rough line, directed inferolaterally, towards the posterior angle. The smooth internal surface is marked by a costal groove, bounded below by the inferior border. The superior border of the groove continues behind the lower border of the neck, but terminates anteriorly at the junction of the middle and anterior thirds of the shaft, anterior to which the groove is absent.

The ridge on the external surface of the shaft (near its posterior angle) gives attachment to an upward continuation of the thoracolumbar fascia and lateral fibres of iliocostalis thoracis. From the second to the tenth ribs, the distance between angle and tubercle increases. Medial to the angle, the external surface gives attachment to a levator costae and is covered by erector spinae. Near the sternal end of this surface an indistinct oblique line, the anterior ‘angle’, separates the attachments of external oblique and serratus anterior (or latissimus dorsi, in the case of the ninth and tenth ribs). The internal intercostal muscle is attached to the costal groove on the internal surface, and separates the bone and the intercostal neurovascular bundle. At its vertebral end, the groove faces down, its borders in the same plane. The shaft broadens near the posterior angle, and the groove reaches its internal surface. The innermost intercostal is attached to the superior rim of the groove, and this attachment occasionally extends to the anterior quarter of the rib. Posteriorly, the superior rim meets the lower border of the neck. The external intercostal muscle is attached to the sharp inferior costal border. The superior border has two lips posteriorly: an inner and an outer lip. The internal intercostal muscles and the innermost intercostal muscles are attached to the inner lip. The external intercostal muscle is attached to the outer lip.

First rib

Most acutely curved and usually shortest, the first rib is broad and flat, its surfaces are superior and inferior, and its borders are internal and external (Fig. 54.8). It slopes obliquely down and forwards to its sternal end. The obliquity of the first ribs accounts for the appearance of pulmonary and pleural apices in the neck.

The head of the first rib is small and round. It bears an almost circular facet, and articulates with the body of the first thoracic vertebra. The neck is rounded and ascends posterolaterally. The tubercle, wide and prominent, is directed up and backwards; medially, an oval facet articulates with the transverse process of the first thoracic vertebra. At the tubercle, the rib is bent, its head turned slightly down, and so the angle and tubercle coincide. The superior surface of the flattened shaft is crossed obliquely by two shallow grooves, separated by a slight ridge, which usually ends at the internal border as a small pointed projection, the scalene tubercle, to which scalenus anterior is attached. The groove anterior to the scalene tubercle forms a bed for the subclavian vein, and the rough area between this and the first costal cartilage gives attachment to the costoclavicular ligament and, more anteriorly, to subclavius. The subclavian artery and (usually) the lower trunk of the brachial plexus pass in the groove behind the tubercle. Behind this, scalenus medius is attached as far as the costal tubercle.

Second rib

The lower parts of the first and second digitations of serratus anterior are attached to a rough prominence that extends from just behind the midpoint of the external surface (Fig. 54.8). The distinct lips of the upper border are widely separated behind; scalenus posterior and serratus posterior superior are attached to the outer lip in front of the angle.

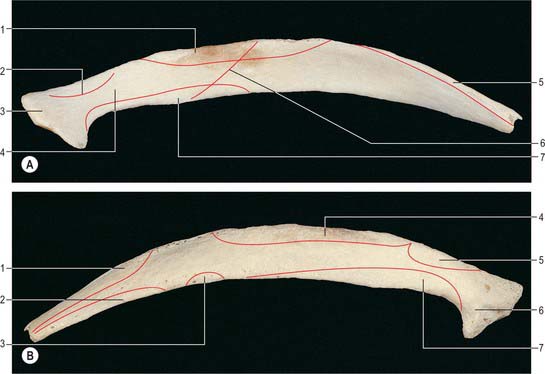

Tenth, eleventh and twelfth ribs

Numerous muscles and ligaments are attached to the twelfth rib (Fig. 54.9). Quadratus lumborum and its anterior covering layer of thoracolumbar fascia are attached to the lower part of its anterior surface in its medial one-half to two-thirds; the upper part is related to the costodiaphragmatic pleural recess. The internal intercostal muscle (medially) and the diaphragm (laterally) are attached at or near the upper border. The lower border gives attachment to the middle lamella of the thoracolumbar fascia and, lateral to quadratus lumborum, to the lateral arcuate ligament and posterior lamella of the thoracolumbar fascia. The lumbocostal ligament is attached posteriorly, close to the head, connecting it to the first lumbar transverse process. The lowest levator costae, longissimus thoracis and iliocostalis are attached to the medial half of the external surface, and serratus posterior inferior, latissimus dorsi and external oblique are attached to its lateral half. The external intercostal muscle is attached along the upper border. These attachments vary: those of the internal intercostal, levator costae and erector spinae merge and those of latissimus dorsi, diaphragm and external oblique may reach the costal cartilage. The lower limit of the pleural sac crosses in front of the rib, approximately at the point where it is crossed by the lateral border of iliocostalis. Its lateral end is usually below the line of costodiaphragmatic pleural reflection and is therefore not covered by pleura.

Costal cartilages

Costal cartilages are the persistent, unossified anterior parts of the cartilaginous models in which the ribs develop. They are flat bars of hyaline cartilage that extend from the anterior ends of the ribs, and contribute greatly to thoracic mobility and elasticity (Fig. 54.7). The upper seven pairs join the sternum; the eighth to tenth articulate with the lower border of the cartilage above; the lowest two have free, pointed ends in the abdominal wall. They increase in length from the first to the seventh, and then decrease to the twelfth. They diminish in breadth from first to last, like the intercostal spaces. The costal cartilages are broad at their costal continuity and taper as they pass forward. The first and second are of even breadth and the sixth to eighth enlarge where their margins are in contact. The first descends a little, the second is horizontal and the third ascends slightly; the others are angulated and incline up towards the sternum or cartilage above, a little anterior to their ribs.

JOINTS

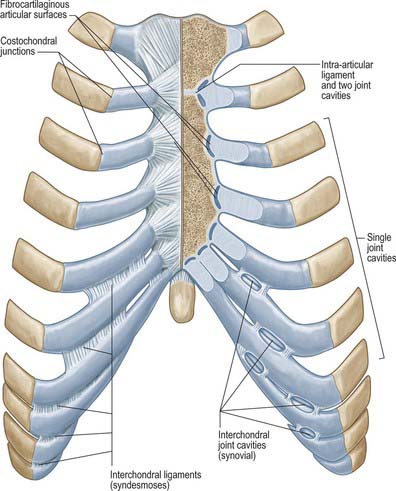

COSTOVERTEBRAL, STERNOCOSTAL AND INTERCHONDRAL JOINTS

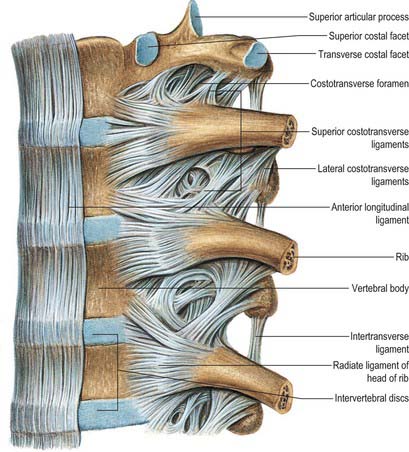

Joints of costal heads

Heads of typical ribs articulate with facets (often termed demifacets) on the margins of adjacent thoracic vertebral bodies and with the intervertebral discs between them (Fig. 54.10). The first and tenth to twelfth ribs articulate with a single vertebra by a simple synovial joint. In the others, an intra-articular ligament bisects the joint, producing a double synovial compartment, so the joint is classified as both compound and complex. Often inaccurately described as plane, their articular surfaces are slightly ovoid and the upper and lower synovial articulations are obtusely angled to each other. The ligaments are capsular, radiate and intra-articular.

The fibrous capsule connects the costal head to the circumference of the articular surface formed by an intervertebral disc and the demifacets of two adjacent vertebrae. Some of the upper fibres traverse their intervertebral foramina to blend with the posterior aspects of the intervertebral discs; the posterior fibres are continuous with the costotransverse ligaments.

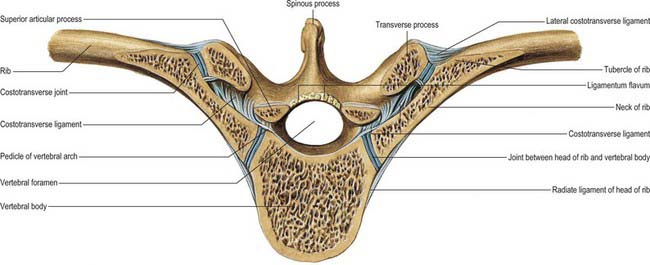

Costotransverse joints

The facet of a costal tubercle articulates reciprocally with the transverse process of its corresponding vertebra (Fig. 54.11). The eleventh and twelfth ribs lack this articulation. In the upper five or six joints, articular surfaces are reciprocally curved, but below this they are flatter (Fig. 54.12). Their ligaments are capsular, costotransverse, superior and lateral costotransverse, and accessory.

Costal heads are so firmly tied to vertebral bodies by radiate and intra-articular ligaments that only slight gliding can occur. Strong ligaments binding costal necks and tubercles to transverse processes also limit movements at costotransverse joints to slight gliding, guided by the shape and direction of the articular surfaces (Fig. 54.12). The facets on the tubercles of the upper six ribs are oval and vertically convex, and fit corresponding concavities on the anterior surfaces of transverse processes; consequently, up and down movements of tubercles involve rotation of costal necks about their long axes. The facets on the seventh to tenth tubercles are almost flat, and face down, medially and backwards; their opposing surfaces are on the upper aspects of transverse processes, and so when these tubercles ascend they also move posteromedially. Both sets of joints move simultaneously and in the same directions: the costal neck therefore moves as if at a single joint in which the two articulations form its ends.

Sternocostal joints

Costal cartilages articulate with small concavities on the lateral sternal borders (chondrosternal articulations) (Fig. 54.13). Perichondrium and periosteum are continuous. The first sternocostal joint is an unusual variety of synarthrosis, and is often inaccurately called a synchondrosis. The second to seventh costal cartilages articulate by synovial joints, although articular cavities are often absent, particularly in the lower joints. Fibrocartilage covers the articular surfaces and also unites the costal cartilages and the sternum in those joints where cavities are absent. The seventh costosternal joint may be synovial or ‘symphysial’. Ligaments involved are capsular, radiate sternocostal, intra-articular and costoxiphoid.

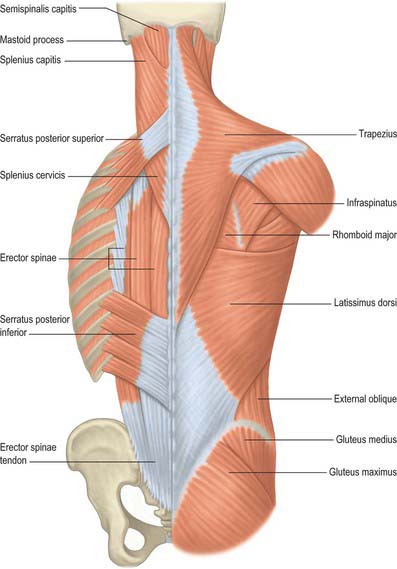

MUSCLES

The intrinsic muscles of the chest wall are the intercostals, subcostales, transversus thoracis, levatores costarum and serratus posterior. Scapular muscles and muscles connecting the upper limb, chest wall and vertebrae, i.e. trapezius, latissimus dorsi, rhomboids major and minor, levator scapulae, pectorales major and minor, subclavius, supra- and infraspinatus, teres major and teres minor, are described in detail in Chapter 46.

INTRINSIC CHEST WALL MUSCLES

Intercostal muscles

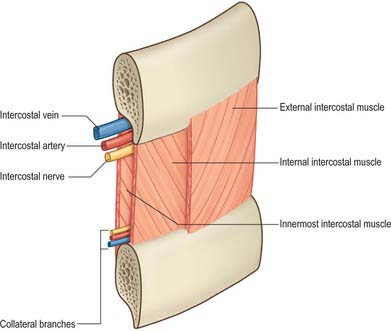

The intercostal muscles are thin multiple layers of muscular and tendinous fibres that occupy the intercostal spaces; their names are derived from their spatial relationship, i.e. the external, internal and innermost intercostals (Fig. 54.14).

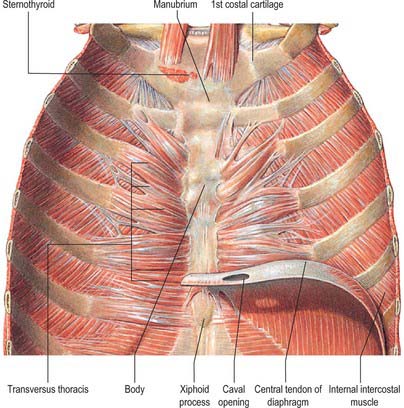

Transversus thoracis

Transversus thoracis (triangularis sternae, sternocostalis) spreads over the internal surface of the anterior thoracic wall (Fig. 54.14). It arises from the lower one-third of the posterior surface of the sternum, the xiphoid process and the costal cartilages of the lower three or four true ribs near their sternal ends. The fibres diverge and ascend laterally as slips that pass into the lower borders and inner surfaces of the costal cartilages of the second, third, fourth, fifth and sixth ribs. The lowest fibres are horizontal, and are contiguous with the highest fibres of transversus abdominis, the intermediate fibres are oblique, and the highest are almost vertical. Transversus thoracis varies in its attachments, not only between individuals but even on opposite sides of the same individual. Like the innermost intercostals and subcostales, transversus thoracis separates the intercostal nerves from the pleura.

Serratus posterior

Serratus posterior superior

Serratus posterior superior (Fig. 54.15) is a thin quadrilateral muscle, external to the upper posterior part of the thorax. It arises by a thin aponeurosis from the lower part of the nuchal ligament, the spines of the seventh cervical and upper two or three thoracic vertebrae and their supraspinous ligaments. It descends laterally, and ends in four digitations attached to the upper borders and external surfaces of the second, third, fourth and fifth ribs, just lateral to their angles. It is superficial to the thoracic part of the thoracolumbar fascia and deep to the rhomboids. The number of digitations can vary from three to six, and the muscle may even be absent.

Mechanism of thoracic cage movement

Breathing involves changing the thoracic volume by altering the vertical, transverse and anteroposterior dimensions of the thorax (see Ch. 58). The diaphragm is the key muscle in this process. Its muscle fibres descend from their relatively ‘high’ anterior sternocostal attachments steeply to the central tendon and obliquely to their complex ‘low’ posterior attachments (see Fig. 58.1). The central tendon is fixed: when the diaphragm contracts, it allows the lower ribcage to move inferiorly and anteriorly without any change to the curvature of the diaphragm. The intercostal muscles maintain the rigidity of the chest wall. The external and internal intercostals, transversus thoracis, subcostales, levatores costarum, serratus posterior superior and serratus posterior inferior can elevate or depress the ribs, and hence can act as accessory muscles of ventilation.

VASCULAR SUPPLY AND LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE OF THE CHEST WALL

ARTERIES

Internal thoracic artery

The internal thoracic artery arises inferiorly from the first part of the subclavian artery, approximately 2 cm above the sternal end of the clavicle, opposite the root of the thyrocervical trunk (see Figs 53.2, 53.3). It descends behind the first six costal cartilages 1 cm from the lateral sternal border and divides at the level of the sixth intercostal space into musculophrenic and superior epigastric branches.

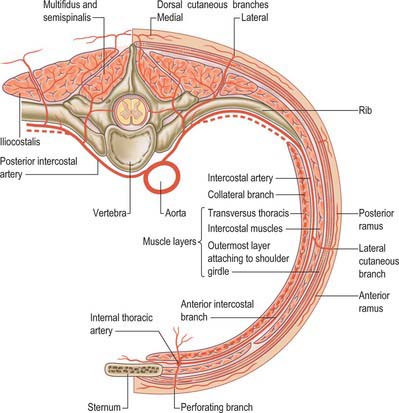

Posterior intercostal arteries

There are usually nine pairs of posterior intercostal arteries (Fig. 54.16). They arise from the posterior aspect of the descending thoracic aorta and are distributed to the lower nine intercostal spaces. Right posterior intercostal arteries are longer, because the aorta deviates to the left: they cross the vertebral bodies behind the oesophagus, thoracic duct and azygos vein, right lung and pleura. Left posterior intercostal arteries turn backwards on the vertebral bodies in contact with the left lung and pleura; the upper two are crossed by the left superior intercostal vein, and the lower by the hemiazygos and accessory hemiazygos veins. The further course of the arteries is the same on both sides. The sympathetic trunk lies anterior to all of the arteries, and the splanchnic nerves descend in front of the lower arteries.

Each artery crosses its intercostal space obliquely towards the angle of the rib above and continues forward in its costal groove. At first between the pleura and internal intercostal membrane as far as the costal angle, it passes between the internal intercostal and innermost intercostal muscles (Fig. 54.17), anastomosing with an anterior intercostal branch from either the internal thoracic or musculophrenic artery. Each artery has a vein above and a nerve below, except in the upper spaces, where the nerve at first lies above the artery. The third posterior intercostal artery anastomoses with the superior intercostal artery and may provide the major supply to the second space. The lower two arteries continue anteriorly into the abdominal wall, where they anastomose with the subcostal, superior epigastric and lumbar arteries. Each posterior intercostal artery has dorsal, collateral, muscular and cutaneous branches.

VEINS

Internal thoracic veins

The internal thoracic veins are venae comitantes of the inferior half of the internal thoracic artery. Near the third costal cartilages, the veins unite and ascend medial to the artery to end in their appropriate brachiocephalic vein (see Fig. 28.14). Tributaries correspond to branches of the artery, and include a pericardiacophrenic vein. The internal thoracic veins have several valves.

Left superior intercostal vein

The left superior intercostal vein drains the second and third (sometimes fourth) left posterior intercostal veins. It ascends obliquely forwards across the left aspect of the aortic arch, lateral to the left vagus and medial to the left phrenic nerve, to open into the left brachiocephalic vein (see Fig. 28.14). It usually receives the left bronchial veins, sometimes the left pericardiacophrenic vein, and connects inferiorly with the accessory hemiazygos vein.

Posterior intercostal veins

The posterior intercostal veins accompany their arteries in 11 pairs. Approaching the vertebral column, each vein receives a posterior tributary that returns blood from the dorsal muscles and skin and the vertebral venous plexuses (see Fig. 55.4A,B). On both sides, the first posterior intercostal vein ascends anterior to the neck of the first rib, arching forward above the pleural dome to end in the ipsilateral brachiocephalic or vertebral vein. On the right side, the second, third and often fourth veins form a right superior intercostal vein that joins the arch of the azygos vein. Veins from the lower spaces drain directly to the azygos. On the left side, the second, third and sometimes fourth veins form a left superior intercostal vein. Veins from the fourth or fifth to eighth intercostal spaces end in the accessory hemiazygos vein, and veins from the ninth to the eleventh intercostal spaces end in the hemiazygos vein.

LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE

Superficial lymphatic vessels of the thoracic wall ramify subcutaneously and converge on the axillary nodes (see Fig. 54.19). Those superficial to trapezius and latissimus dorsi unite to form 10 or 12 trunks which end in the subscapular nodes. Those in the pectoral region, including vessels from the skin covering the periphery of the breast and its subareolar plexus, run back, collecting those superficial to serratus anterior, to reach the pectoral nodes. Vessels near the lateral sternal margin pass between the costal cartilages to the parasternal nodes, but also anastomose across the sternum. A few vessels from the upper pectoral region ascend over the clavicle to the inferior deep cervical nodes. Lymph from the deeper tissues of the thoracic walls drains mainly to the parasternal, intercostal or diaphragmatic nodes.

INNERVATION OF THE CHEST WALL

THORACIC VENTRAL SPINAL RAMI

There are 12 pairs of thoracic ventral rami. The upper 11 lie between the ribs (intercostal nerves), and the twelfth lies below the last rib (subcostal nerve) (Figs 54.3, 54.18). Each is connected with the adjoining ganglion of the sympathetic trunk by grey and white rami communicantes; the grey ramus joins the nerve proximal to the point at which the white ramus leaves it. Intercostal nerves are distributed primarily to the thoracic and abdominal walls. The first two nerves supply fibres to the upper limb in addition to their thoracic branches, the next four supply only the thoracic wall, and the lower five supply both thoracic and abdominal walls. The subcostal nerve is distributed to the abdominal wall and the gluteal skin. Communicating branches link the intercostal nerves posteriorly in the intercostal spaces, and the lower five nerves communicate freely in the abdominal wall.

First to sixth thoracic ventral rami

Each intercostal nerve gives off a collateral and a lateral cutaneous branch before it reaches the angle of the adjoining ribs (Fig. 54.18). The collateral branch follows the inferior border of its space in the same intermuscular place as the main nerve, which it may rejoin before it is distributed as an additional anterior cutaneous nerve. The lateral cutaneous branch accompanies the main nerve a little way and then pierces the intercostal muscles obliquely. With the exception of the lateral cutaneous branches of the first and second intercostal nerves, each divides into anterior and posterior rami that subsequently pierce serratus anterior. Anterior branches run forwards over the border of pectoralis major to supply the overlying skin; those of the fifth and sixth also supply twigs to a variable number of upper digitations of external oblique. Posterior branches run backwards and supply the skin over the scapula and latissimus dorsi.

The lateral cutaneous branch of the second intercostal nerve is the intercostobrachial nerve (see Fig. 46.30). It crosses the axilla to gain the medial side of the arm and joins a branch of the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm. It then pierces the deep fascia of the arm, and supplies the skin of the upper half of the posterior and medial parts of the arm, communicating with the posterior cutaneous branch of the radial nerve. Its size is in inverse proportion to the size of the medial cutaneous nerve. A second intercostobrachial nerve often branches off from the anterior part of the third lateral cutaneous nerve and sends filaments to the axilla and the medial side of the arm.

Seventh to eleventh thoracic ventral rami

The ventral rami of the seventh to eleventh thoracic nerves are continued anteriorly from the intercostal spaces into the abdominal wall; their further course is described in Chapter 62.

Twelfth thoracic ventral ramus (subcostal nerve)

The ventral ramus of the twelfth thoracic nerve (subcostal nerve) is larger than the others and gives a communicating branch to the first lumbar ventral ramus (sometimes termed the dorsolumbar nerve). Like the intercostal nerves, it soon gives off a collateral branch and then accompanies the subcostal vessels along the inferior border of the twelfth rib, passing behind the lateral arcuate ligament and kidney and in front of the upper part of quadratus lumborum. It perforates the aponeurosis of the origin of transversus abdominis and passes forwards between that muscle and internal oblique, to be distributed in the same manner as the lower intercostal nerves. The subcostal nerve connects with the iliohypogastric nerve of the lumbar plexus and sends a branch to pyramidalis. Its lateral cutaneous branch pierces the internal and external oblique muscles and supplies the lowest slip of the latter. It usually descends over the iliac crest 5 cm behind the anterior superior iliac spine (see Fig. 61.4) and is distributed to the anterior gluteal skin; some filaments reach as low as the greater trochanter of the femur.

THORACIC DORSAL SPINAL RAMI

Medial branches of the upper six thoracic dorsal rami pass between and supply semispinalis thoracis and multifidus; they then pierce the rhomboids and trapezius, and reach the skin near the vertebral spines (see Fig. 43.6). Medial branches of the lower six thoracic dorsal rami are distributed mainly to multifidus and longissimus thoracis; occasionally they give filaments to the skin in the median region. Lateral branches increase in size from above downwards. They run through or deep to longissimus thoracis to the interval between it and iliocostalis cervicis, and supply these muscles and levatores costarum; the lower five or six also give off cutaneous branches, which pierce serratus posterior inferior and latissimus dorsi in line with the costal angles (see Fig. 43.6). The lateral branches of a variable number of the upper thoracic rami also supply the skin. The lateral branch of the twelfth sends a filament medially along the iliac crest, then passes down to the skin of the anterior part of the gluteal region.

BREAST

The breasts form a secondary sexual feature of females and are the source of nutrition for the neonate. They are also present in a rudimentary form in males. The breasts are the site of malignant change in as many as one in ten women. For reviews of normal breast structure, consult Ellis et al (1993).

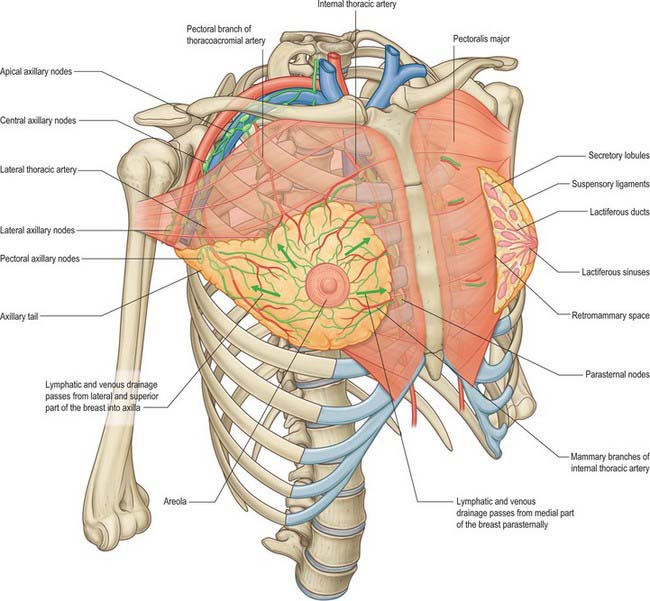

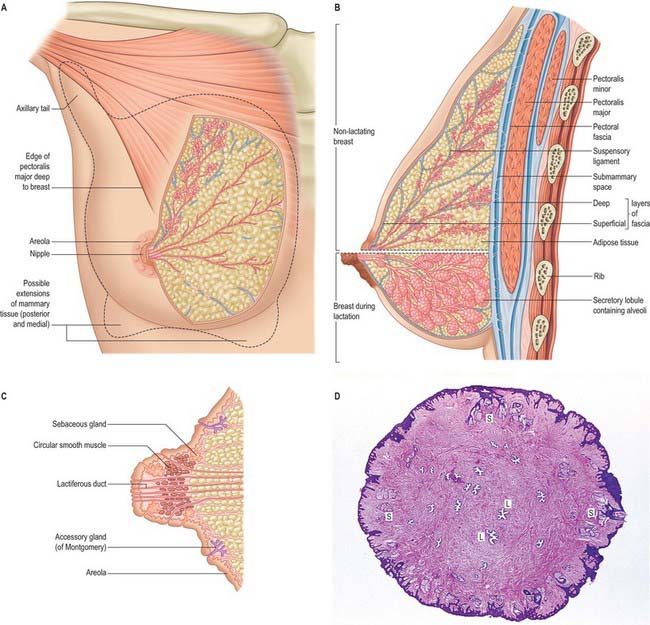

In young adult females, each breast is a rounded eminence lying within the superficial fascia, largely anterior to the upper thorax but spreading laterally to a variable extent (Figs 54.19, 54.20B). Breast shape and size depend upon genetic, racial and dietary factors, and the age, parity and menopausal status of the individual. Breasts may be hemispherical, conical, variably pendulous, piriform or thin and flattened. In the adult female, the base of the breast, i.e. its attached surface, extends vertically from the second or third to the sixth rib, and in the transverse plane from the sternal edge medially almost to the midaxillary line laterally. The superolateral quadrant is prolonged towards the axilla along the inferolateral edge of pectoralis major, from which it projects a little, and may extend through the deep fascia up to the apex of the axilla (the axillary tail of Spence). The trunk superficial fascial system splits to enclose the breast to form the anterior and posterior lamellae. Posterior extensions of the superficial fascial system connect the breast to the pectoralis fascia, part of the deep fascial system. The inframammary crease is a zone of adherence of the superficial fascial system to the underlying chest wall at the inferior crescent of the breast.

The nipple projects from the centre of the breast anteriorly (Fig. 54.20C,D). Its shape and projection varies from cylindrical and rounded at the top, to hemispherical, to flattened, depending on nervous, hormonal, developmental and other factors. The level of the nipple varies widely. In females, its site is dependent on the size and shape of the breasts, but it overlies the fourth intercostal space in most young women. In the male, the nipple is usually sited in the fourth intercostal space in the midclavicular line. In the young adult of either sex, the nipples are usually positioned 20–23 cm from the suprasternal notch in the midclavicular line and 20–23 cm apart in the horizontal plane. With increasing age and parity, female breasts adopt a more ptotic shape and the nipple position drops either to the level of the inframammary crease or lies below this surface landmark. In the nulliparous, it is pink, light brown or darker, depending on the general melanization of the body. Occasionally, the nipple may not evert during prenatal development, in which case it remains permanently retracted and so causes difficulty in suckling.

NIPPLE AND AREOLA

The skin covering the nipple and the surrounding areola (the disc of skin that circles the base of the nipple) has a convoluted surface (Fig. 54.20C). It contains numerous sweat and sebaceous glands which open directly onto the skin surface. The oily secretion of these specialized sebaceous glands acts as a protective lubricant and facilitates latching of the neonate during lactation: the glands are often visible in parous women, arranged circumferentially as small elevations, Montgomery’s tubercles, around the areola close to the margin. Other areolar glands, which are intermediate in structure between mammary and sweat glands, become enlarged in pregnancy and lactation as subcutaneous tubercles. The sebaceous glands of the areola usually lack hair follicles. The skin of the nipple and areola is rich in melanocytes and is therefore typically darker than the skin covering the remainder of the breast: further darkening occurs during the second month of pregnancy, and subsequently persists to a variable degree.

SOFT TISSUE

The breasts are composed of lobes which contain a network of glandular tissue consisting of branching ducts and terminal secretory lobules in a connective tissue stroma (see Fig. 54.26A). The terminal duct lobular unit is the functional milk secretory component of the breast and pathologically gives rise to primary malignant lesions within the breast. Although the lobes are usually described as discrete territories, they intertwine in three dimensions and merge at their edges; they cannot be distinguished during surgery. The connective tissue stroma that surrounds the lobules is dense and fibrocollagenous, whereas intralobular connective tissue has a loose texture that allows the rapid expansion of secretory tissue during pregnancy (see Fig. 54.26B). Fibrous strands or sheets consisting of condensations of connective tissue extend between the layer of deep fascia that covers the muscles of the anterior chest wall and the dermis. These suspensory ligaments (of Astley Cooper) are often well developed in the upper part of the breast and support the breast tissue, helping to maintain its non-ptotic form. Elsewhere in the normal breast, fibrous tissue surrounds the glandular components and extends to the skin and nipple, assisting the mechanical coherence of the gland. The interlobar stroma contains variable amounts of adipose tissue which is responsible for much of the increase in breast size at puberty.

VASCULAR SUPPLY AND LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE

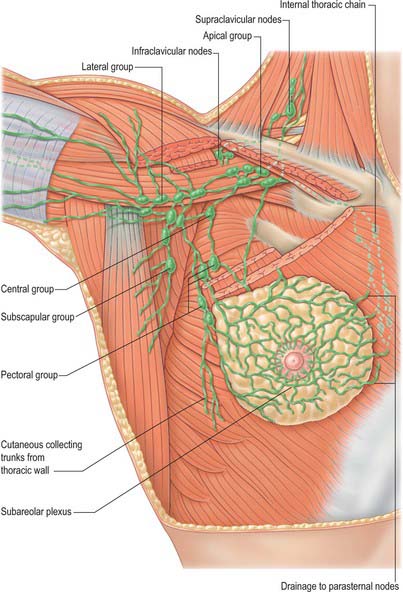

Lymphatic drainage

The lymphatic flow of the breast is of great clinical significance because metastatic dissemination occurs principally by the lymphatic routes. The dominant lymphatic drainage of the breast is derived from the dermal network. The breast lymphatics branch extensively and do not contain valves: lymphatic blockage through tumour occlusion may therefore result in reverse blood flow through the lymphatic channels. The direction of lymphatic flow within the breast parallels the major venous tributaries and enters the regional lymph nodes via the extensive periductal and perilobular network of lymphatic channels. Most of these lymphatics drain into the axillary group of regional lymph nodes either directly or through the retroareolar lymphatic plexus (see Fig. 46.28). Dermal lymphatics also penetrate pectoralis major to join channels that drain the deeper parenchymal tissues, and then follow the vascular channels to terminate in the subclavicular lymph nodes. Lymphatics from the left breast ultimately terminate in the thoracic duct and subsequently the left subclavian vein. On the right, the lymphatics ultimately drain into the right subclavian vein near its junction with the internal jugular vein. Part of the medial side of the right breast drains towards the internal thoracic group of lymph nodes. The internal thoracic chain may drain inferiorly via the superior and inferior epigastric lymphatic routes to the groin. Connecting lymphatics across the midline may provide access of lymphatic flow to the opposite axilla.

Axillary nodes receive more than 75% of the lymph from the breast (Fig. 54.21). There are 20–40 nodes, grouped artificially as pectoral (anterior), subscapular (posterior), central and apical. Surgically, the nodes are described in relation to pectoralis minor. Those lying below pectoralis minor are the low nodes (level 1), those behind the muscle are the middle group (level 2), while the nodes between the upper border of pectoralis minor and the lower border of the clavicle are the upper or apical nodes (level 3). There may be one or two other nodes between pectoralis minor and major; this interpectoral group of nodes are also known as Rotter’s nodes. Efferent vessels directly from the breast pass round the anterior axillary border through the axillary fascia to the pectoral lymph nodes; some may pass directly to the subscapular nodes. A few vessels pass from the superior part of the breast to the apical axillary nodes, sometimes interrupted by the infraclavicular nodes or by small, inconstant, interpectoral nodes. Most of the remainder drains to parasternal nodes from the medial and lateral parts of the breast; they accompany perforating branches of the internal thoracic artery. Lymphatic vessels occasionally follow lateral cutaneous branches of the posterior intercostal arteries to the intercostal nodes.

Lymphatic drainage in breast cancer and role of sentinel lymph node biopsy

Lymphatic mapping with sentinel lymph node biopsy has become an important technique in the staging of patients with early breast cancer. A radiolabelled colloid is injected into either the subareolar tissue of the index quadrant of the breast or the peritumoural tissue and intradermal tissue overlying the primary breast cancer. At the time of surgery, a vital blue dye is injected after general anaesthesia is established. The combination of radioisotope and dye provides the most accurate means of localizing the sentinel node (Rubio & Klimberg 2001, Tanis et al 2001). The sentinel node represents the first draining node of the axilla and is surgically removed for careful histopathological analysis to detect the presence of metastases. The sentinel node procedure seeks to identify this first draining node, and, if negative for cancer metastases, avoids more radical surgery in women who have no cancer spread, thus reducing morbidity associated with axillary dissection. In women who are found to have metastases to the axillary node, selective treatment to the axilla by completion axillary dissection or radiotherapy is offered. The majority of sentinel nodes are found in the low axilla within the level I group of nodes but can sometimes be found in higher echelon axillary nodes. This occurs in 5–10% of cases; the nodes are termed skip-metastases. Occasionally, the sentinel node is identified in an extra-axillary position, either within the breast parenchyma in an intramammary lymph node, the internal thoracic lymph node chain, or in the supraclavicular fossa.

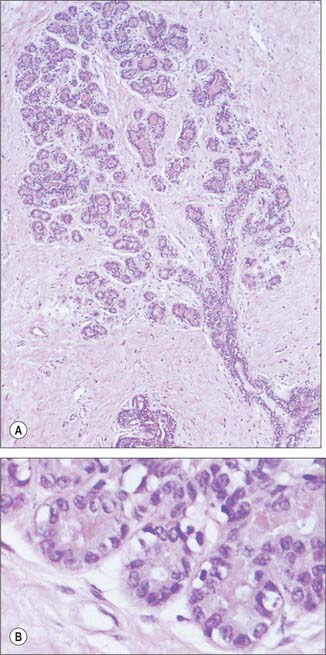

MICROSTRUCTURE

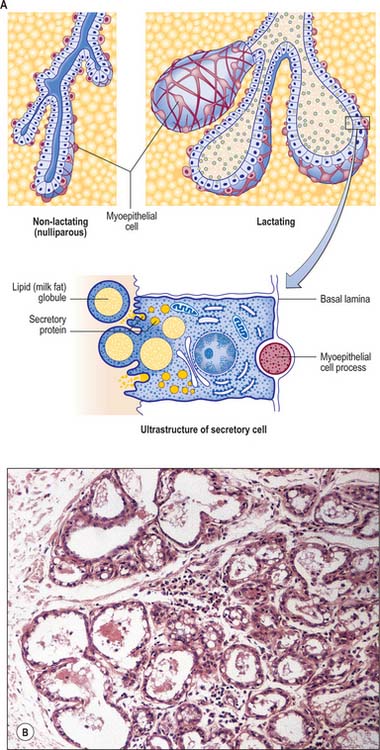

The microstructure of breast tissue varies with age, time in the menstrual cycle, pregnancy and lactation. The following description relates to the mature, resting breast. For most of their lengths, the ducts are lined by columnar epithelium (Fig. 54.22). In the larger ducts, this is two cells thick, but, in the smaller ones, only a single layer of columnar or cuboidal cells is present. The bases of these cells are in close contact with numerous myoepithelial cells of ectodermal origin, similar to those of certain other glandular epithelia (see Figs 2.3, 54.26A). Myoepithelial cells are so numerous that they form a distinct layer surrounding the ducts and presumptive alveoli and give the epithelium a bilayered appearance.

Lactiferous ducts draining each lobe of the breast pass through the nipple and open onto its tip as 15–20 orifices. Near its orifice, each of these ducts is slightly expanded as a lactiferous sinus, which, in the lactating breast, is further dilated by the presence of milk. Each lactiferous duct is therefore connected to a system of ducts and lobules, surrounded by connective tissue stroma, collectively forming a lobe of the breast. Lobules consist of the portions of the glands that have secretory potential. Their structure varies according to hormonal status. In the mature resting breast, each lobule consists of a cluster of blind-ended, branched ductules whose termini lack terminal alveoli (acini), which are the sites of milk secretion in the lactating breast (see Fig. 54.26B). The stratified cuboidal lining is replaced by keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, continuous with the epidermis, close to the openings of the lactiferous ducts on the nipple. Shed squames may sometimes block the duct apertures in the non-pregnant breast.

BREAST CANCER

Breast cancer is a common disease, particularly in postmenopausal women (see Fentiman 1993). Each year in the United Kingdom, there are approximately 40,000 new cases diagnosed and 14,000 deaths. Male breast cancers make up 1% of all mammary malignancies and may include tissue beyond the areolar boundary.

If a breast lump has to be surgically removed, the incision should be based, whenever possible, in the relaxed skin tension lines, for the best cosmetic results. In women with sizeable malignant lesions where breast conservation surgery is to be attempted, the skin incision should be planned with consideration of the possible requirement of the need for a subsequent mastectomy if the margins of excision are incompletely excised by pathological criteria. Most women with single breast cancers up to 4 cm in diameter are treated by breast conservation rather than mastectomy. This is a combination of surgery (tumour excision and axillary lymph node sampling or clearance) together with external beam radiotherapy. Patients with larger tumours are treated by modified radical mastectomy with axillary lymph node clearance. During axillary dissection to clear the axillary lymph nodes, the nerve to serratus anterior, the thoracodorsal vessels, the nerve to latissimus dorsi, and the medial and lateral pectoral nerves are all identified and carefully preserved. The boundaries of the axillary dissection are the nerve to serratus anterior medially, the thoracodorsal pedicle laterally and the axillary vein superiorly (see Fig. 46.30). The posterior limit of the dissection is the ventral surface of subscapularis. The superomedial limit of a level I axillary dissection extends to the lateral border of pectoralis minor at the apex of the axilla, a level II dissection extends to the medial border of pectoralis minor, and a level III dissection extends beyond the medial border until it reaches the point where the axilla is limited by the first rib (the latter is easily distinguished by its flat lateral surface, easily palpable at surgery). Failure to preserve the nerve to serratus anterior will result in winging of the scapula. The intercostobrachial nerve is often sacrificed in an axillary lymph node clearance operation, and this may result in anaesthesia of a narrow strip of sensation in the upper medial border of the arm.

Reconstructive surgery for breast cancer disease

Breast reconstruction may be performed at the time of mastectomy for breast cancer, or at a later stage (Serletti & Moran 2000). During a mastectomy where an immediate breast reconstruction is planned, the glandular breast tissue is removed either through a conventional mastectomy skin incision or in association with preservation of the native breast skin, a form of mastectomy termed a skin-sparing mastectomy. Patient selection is important to minimize risks of breast cancer recurrence in the skin of the reconstructed breast mound or associated lymph nodes. In an implant-based immediate breast reconstruction, a tissue expander is placed beneath the submusculofascial plane consisting of pectoralis major, in continuity laterally under serratus anterior with the intervening fascia, and the abdominal fascia inferiorly. The lower fibres of the attachment of pectoralis major to the sixth rib need to be detached, otherwise the implant will be placed too high on the chest wall. The tissue expander has to stretch the potential space below this musculofascial plane to match the space created by the removed breast beneath the subcutaneous plane and the deep fascia overlying pectoralis major. The tissue expander is subsequently replaced by a silicone or saline breast implant.

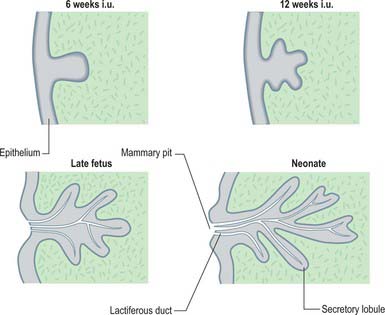

DEVELOPMENT

The thoracic ectodermal ingrowths branch into 15–20 solid buds of ectoderm which will become the lactiferous ducts and their associated lobes of alveoli in the fully formed gland. They are surrounded by somatopleuric mesenchyme which forms the connective tissue, fat and vasculature which is invaded by the mammary nerves. Continued cell proliferation, elongation and further branching produces the alveoli and defines the duct system. Nipple formation begins at day 56, primitive ducts (mammary sprouts) develop at 84 days and canalization occurs at about the 150th day. During the last 2 months of gestation the ducts become canalized; the epidermis at the point of original development of the gland forms a small mammary pit, into which the lactiferous tubules open (Fig. 54.23). Perinatally the nipple is formed by mesenchymal proliferation. Should this process fail, the ducts open into shallow pits. Rarely, the nipple may not develop (athelia), a phenomenon that occurs more commonly in accessory breast tissue.

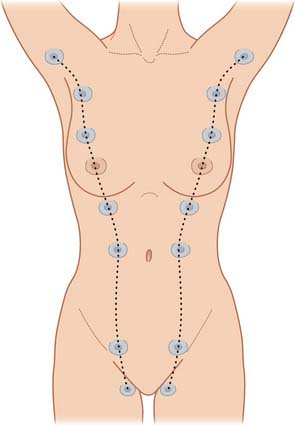

Accessory breast tissue and nipples

Polymastia (supernumerary breasts) and polythelia (supernumerary nipples) may develop in males and females anywhere along the length of the mammary ridges (milk lines; Fig. 54.24). Conversely, breast tissue may not develop at all (amastia) or there may be nipple development but no breast tissue (amazia). Supernumerary breast development occurs in most cases in the thoracic region, just inferior to the normal breast (90%), but may also occur in the axillary (5%) and abdominal regions (5%). Polythelia occurs along the same mammary line but no underlying glandular tissue develops. About 1% of the female population has this condition, but it is more common in males, where the accessory nipple may be mistaken for a mole.

AGE-RELATED CHANGES

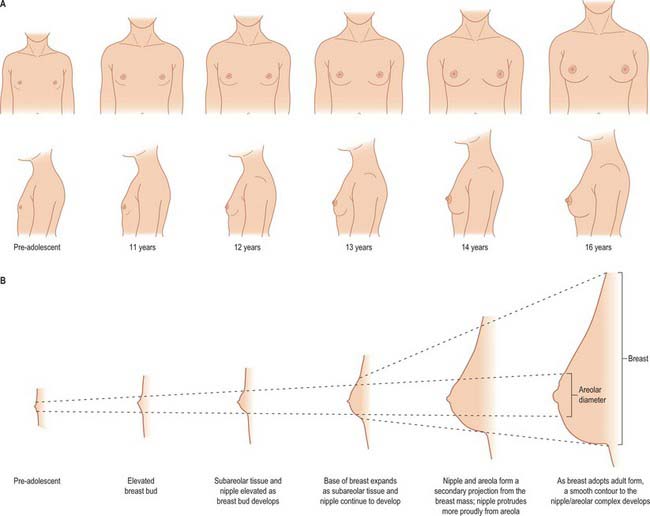

Puberty

From puberty onwards, externally recognizable breast development (thelarche) can be divided into five separate phases (Fig. 54.25): elevation of the breast bud (phase I); glandular subareolar tissue is present and both nipple and breast project from the chest wall as a single mass (phase II); the areola increases in diameter and becomes pigmented, and there is proliferation of palpable breast tissue (phase III); further pigmentation and enlargement occurs in the areola, so that the nipple and areola form a secondary mass anterior to the main part of the breast (phase IV); a smooth contour to the breast develops (phase V).

Changes during the menstrual cycle

Changes occur in the breast tissues in the menstrual cycle. In the follicular phase (days 3–14), the stroma becomes less dense. Various changes including luminal expansion take place in the ducts; there are occasional mitoses but no secretion. In the luteal phase (days 15–28), there is a progressive increase in stromal density and the ducts have an open lumen that contains secretion, associated with flattening of the epithelial cells. Cell proliferation is maximal on day 26 and thereafter the ductal system undergoes reduction; epithelial cell apoptosis is greatest on day 28 of the cycle. There are also changes in blood flow, which are greatest at midcycle, and an increase in the water content of the stroma in the second half of the menstrual cycle.

CHANGES ASSOCIATED WITH PREGNANCY AND LACTATION

Lactation

Milk distends the alveoli so that the cells flatten as secretion increases (Figs 54.20B, 54.26B,C). The alveolar cell cytoplasm accumulates membrane-bound granules of casein and other milk proteins, and these are released from the apical plasma membrane by membrane fusion (merocrine secretion; see Ch. 2). Lipid vacuoles are formed directly in the apical cytoplasm as small lipid droplets which fuse with each other to create large ‘milk vacuoles’ up to 10 μm across, that frequently protrude from the cell surface. These are released as intact lipid droplets with a thin surround of apical plasma membrane and adjacent cytoplasm (apocrine secretion). On hormonal stimulation by oxytocin, myoepithelial cells contract to expel alveolar secretions into the ductal system in readiness for suckling.

Postlactation

When lactation ceases, which may be as long as 3½ years, or even longer if frequent suckling is maintained, the secretory tissue undergoes some involution, but the ducts and alveoli never return completely to the pre-pregnant state. Two major processes are responsible for the regression of the alveolar–ductal system: a reduction in epithelial cell size and a reduction in cell numbers mediated via apoptosis (see Ch. 1). Gradually the breast tissue reverts to its resting state. If another pregnancy occurs, the resting glandular tissue is reactivated, and the process outlined above recurs. Up to the age of 50 years, increasing amounts of elastic tissue tend to be laid down around vessels and ducts (elastosis), and also in the stroma. Elastosis does not normally continue into later life.

MALE BREAST

The male breast remains rudimentary throughout life. It is formed of small ducts (without lobules or alveoli) or solid cellular cords and a little supporting fibroadipose tissue (see Ellis et al 1993). Slight temporary enlargement may occur in the newborn, reflecting the influence of maternal hormones, and again at puberty. The areola is well developed, although limited in area, and the nipple is relatively small. It is usually stated that the ducts do not extend beyond the areola in a male breast, but glandular tissue can be more extensive.

SURGICAL ACCESS TO THORACIC VISCERA

A posterolateral incision is most commonly used in thoracic surgery for unilateral pulmonary resections, bullectomy, unilateral lung volume reduction surgery, chest wall resection and oesophageal surgery (Fry 2000). The patient is placed in a lateral decubitus position with adequate support of the elbow, axilla and knee with padding. The standard approach is via an incision from the anterior axillary line which curves about 4 cm below the tip of the scapula and then vertically between the posterior midline and medial edge of the scapula. The incision is usually extended to the level of the spine of scapula. Overall, the incision forms an S-shape in the fifth intercostal space. The sixth or seventh intercostal space is used in oesophageal surgery.

Ellis H, Colborn GL, Skandalakis JE. Surgical embryology and anatomy of the breast and its related anatomic structures. Surg Clin North Am. 1993;73:611-632.

Fentiman IS. Detection and Treatment of Early Breast Cancer. London: Martin Dunitz, 1993.

Fry WA. Thoracic incisions. Shields TW, LoCicero JIII, Ponn RB. General Thoracic Surgery. 5th edn.. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:367-374.

Kurihara Y, Yakushiji YK, Matsumoto J, Ishikawa T, Hirata K. The ribs: anatomic and radiologic considerations. Radiographics. 1999;19:105-119.

Includes some chest wall and ribcage abnormalities..

Rubio IT, Klimberg S. Techniques of sentinel lymph node biopsy. Semin Surg Oncol. 2001;20:214-223.

Serletti JM, Moran SL. Microvascular reconstruction of the breast. Semin Surg Oncol. 2000;19:264-271.

Tanis PJ, Nieweg OE, Valdes Olmos RA, Kroon BB. Anatomy and physiology of lymphatic drainage of the breast from the perspective of sentinel node biopsy. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:399-409.

Yap LH, Whiten SC, Forster A, Stevenson JH. The anatomical and neurophysiological basis of the sensate free TRAM and DIEP flaps. Br J Plast Surg. 2002;55:35-45.