Chest Trauma

Disorders

Signs and Symptoms

1. Pain in the chest after blunt chest trauma

2. Pain that worsens with inspiration

3. Point tenderness over the fractured rib(s)

4. Crepitus and deformity, occasionally detected on palpation

5. Fractured ribs usually occur along the side of the chest. Pushing on the sternum while the patient lies supine will produce pain at the fracture site, instead of at the point of contact

Treatment

1. Care for any open chest wounds.

a. Cover the wound quickly, especially if there is air bubbling, to avoid “sucking” chest wound (see Open [“Sucking”] Chest Wound, later).

b. Use a petrolatum-impregnated gauze, heavy cloth, or adhesive tape for the dressing.

2. Treat an isolated rib fracture.

a. Administer an oral analgesic, and instruct the patient to rest.

b. Note that thoracic taping and splinting are contraindicated so that the patient can take full unimpeded inspirations.

c. Encourage the patient to cough or deep-breathe at least 10 times per hour to prevent atelectasis.

3. Treat multiple rib fractures.

a. Be aware that multiple fractures are associated with higher risk for serious underlying injuries.

b. Cushion the patient in a position of comfort, and frequently reevaluate the patient’s ability to breathe.

c. Do not tape or tightly wrap the ribs because this might prevent complete reexpansion of the lung with inspiration, leading the patient to take only shallow, inadequate breaths and possibly leading to atelectasis and pneumonia. Provide analgesics so that the patient may take at least 10 deep breaths or give one good cough every hour.

d. Evacuate the patient as soon as possible. If the chest injury is on one side, transport the patient with the injured side down to facilitate lung expansion and oxygenation of the blood on the uninjured side.

Flail Chest

Treatment

1. Immediately arrange for evacuation of the patient. A small or moderate flail segment can be tolerated for 24 to 48 hours, after which it may need to be managed with mechanical ventilation.

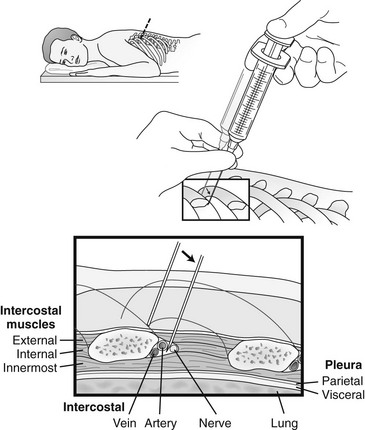

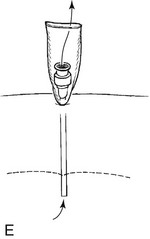

2. Administer intercostal nerve block(s) (Fig. 15-1) to assist in short-term management of pain and pulmonary toilet.

3. Place a bulky pad of dressings, rolled-up extra clothing, or a small pillow gently over the site, or have the patient splint the arm against the injury to stabilize the flail segment and relieve some of the pain.

a. Use soft and lightweight materials.

b. Use large strips of tape to hold the pad in place.

c. Do not tape entirely around the chest because this will restrict breathing efforts.

d. Do not allow the object to restrict breathing in any manner.

4. If the patient is unable to walk, transport him or her lying on the back or injured side.

5. If the patient is severely short of breath, assist with mouth-to-mouth rescue breathing. Time your breaths with those of the patient, and breathe gently to provide added air during the patient’s inspirations.

Pneumothorax/Hemothorax

1. Pain that worsens with inspiration

3. Unilateral decreased or absent breath sounds

4. Resonance on percussion with a pneumothorax; flat or dull on percussion with a hemothorax

5. Subcutaneous emphysema (in the case of pneumothorax)

6. Pneumothorax can be identified by loss of the “comet tails” or loss of pleural sliding on ultrasound examination.

Tension Pneumothorax

Open (“Sucking”) Chest Wound

Treatment

1. Place a petrolatum-impregnated gauze pad on top of the wound, cover it with a 4 × 4 inch gauze pad, and tape it on all four sides (Fig. 15-3).

2. Observe closely for signs of tension pneumothorax, and treat as described earlier, with pleural decompression.

3. If a penetrating object remains impaled in the chest, do not remove it. If necessary, carefully shorten the external portion of the penetrating object (e.g., break off the arrow). Place a petrolatum gauze dressing next to the skin around the object, and stabilize it with layers of bulky dressings or pads.

4. A patient with an open chest wound below the nipple line may also have an injury to an intra-abdominal organ (see Chapter 16).

Pericardial Tamponade

Treatment

1. The only temporizing measure pending evacuation is pericardiocentesis. This procedure should be done in the wilderness only if there is a high index of suspicion, coupled with shock (and impending death) unresponsive to other resuscitative efforts.

2. Advance a long (≈15 cm [5.9 inches]), 16- to 18-gauge needle with an overlying catheter through the skin 1 to 2 cm (0.4 to 0.8 inches) below and to the left of the xiphoid. The needle is advanced at a 45-degree angle with the tip directed at the tip of the left scapula.

3. After the pericardial sac is entered, aspirate blood with a syringe until the patient’s condition improves. Repeat aspiration as the patient’s condition warrants.