Chapter 15

Chest Pains and Angina

1. Are most emergency room (ER) visits for chest pain caused by acute coronary syndromes (ACS)?

2. What are the other important causes of chest pains besides chronic stable angina and ACS?

The differential diagnosis for chest pains include the following:

Coronary artery spasm (Prinzmetal angina, cocaine abuse)

Coronary artery spasm (Prinzmetal angina, cocaine abuse)

Musculoskeletal pain and cervical radiculopathies (costochondritis)

Musculoskeletal pain and cervical radiculopathies (costochondritis)

Gastrointestinal (GI) causes (reflux, esophagitis, esophageal spasm, peptic ulcer disease, gallbladder disease, and esophageal rupture [Boerhaave syndrome])

Gastrointestinal (GI) causes (reflux, esophagitis, esophageal spasm, peptic ulcer disease, gallbladder disease, and esophageal rupture [Boerhaave syndrome])

3. Does an elevated troponin level make the diagnosis ACS?

Not necessarily. Although troponin elevations are fairly sensitive and specific for myocardial necrosis, it is well known that other conditions can also be associated with elevations in cardiac troponins. Importantly, troponin elevation can occur with pulmonary embolus and is in fact associated with a worse prognosis in cases of pulmonary embolus in which the troponin levels are elevated. Myopericarditis (inflammation of the myocardium and pericardium) may also cause elevated troponin levels. In addition, aortic dissection that involves the right coronary artery may lead to secondary MI. Further, troponins may be modestly chronically elevated in patients with severe chronic kidney disease. Troponin elevation has also been noted in patients with acute stroke. Studies to delineate the etiology of this are ongoing.

5. What are the associated symptoms that persons with angina may experience in addition to chest discomfort?

Radiating pains. Patients may describe pains or discomfort that radiate to the back (typically midscapula), the neck, the jaw, or down one or both arms. They may also describe a numbness-type sensation in the arm.

Radiating pains. Patients may describe pains or discomfort that radiate to the back (typically midscapula), the neck, the jaw, or down one or both arms. They may also describe a numbness-type sensation in the arm.

6. What are the major risk factors for CAD?

Sex. Males are at higher risk of developing CAD, particularly earlier in life.

Sex. Males are at higher risk of developing CAD, particularly earlier in life.

Family history of premature CAD. This is traditionally defined as a father, mother, brother, or sister who first developed clinical CAD at age younger than 45 to 55 years for men and at age younger than 55 to 60 years for women.

Family history of premature CAD. This is traditionally defined as a father, mother, brother, or sister who first developed clinical CAD at age younger than 45 to 55 years for men and at age younger than 55 to 60 years for women.

7. What symptoms and findings make it more (or less) likely that the patient’s chest pains are due to angina (or that the patient has ACS)?

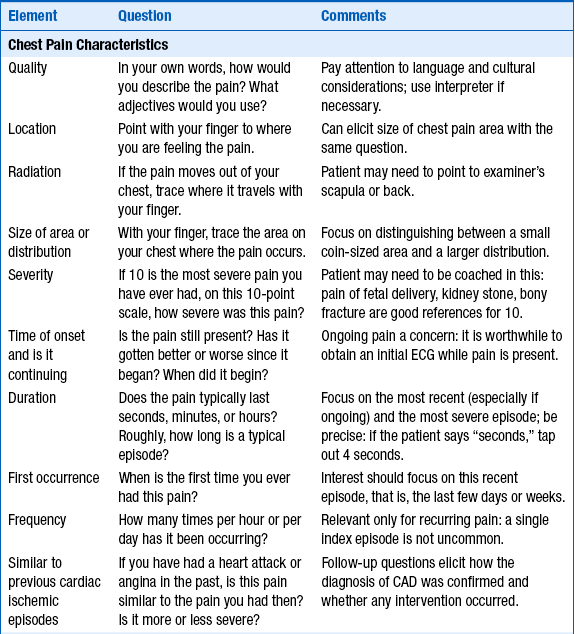

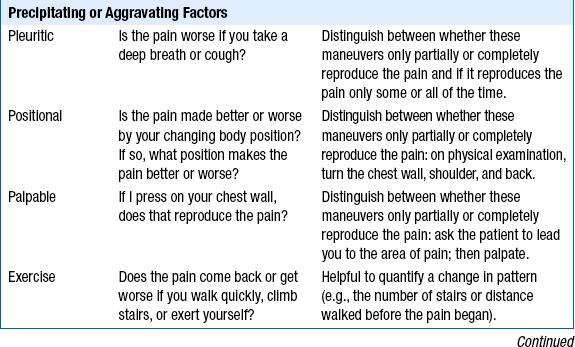

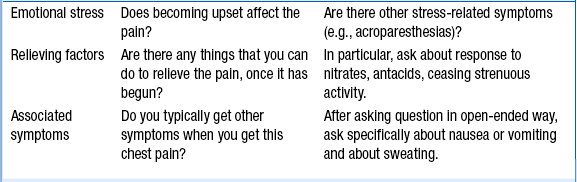

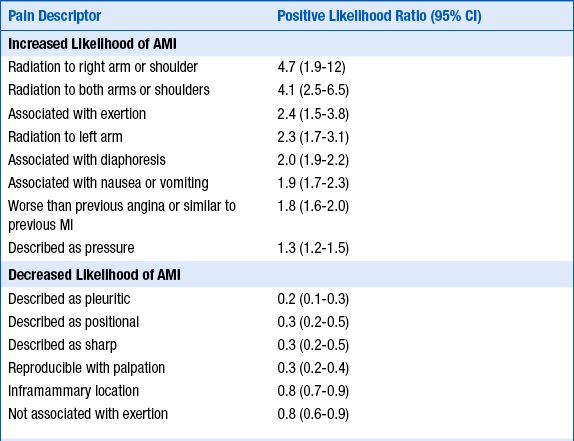

The answer to this question is given in Tables 15-1 and 15-2, which are taken from an excellent review article on this subject in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). The tables summarize many of the relevant questions and the value of the chest pain characteristics in distinguishing angina and ACS-MI pain from other causes. It is important to remember, no single element of chest pain history is a powerful enough predictor to use alone to rule out ACS.

TABLE 15-1

SPECIFIC DETAILS OF THE CHEST PAIN HISTORY HELPFUL IN DISTINGUISHING ANGINAL CHEST PAIN IN PATIENTS WITH MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION FROM NONCARDIAC CAUSES

CAD, Coronary artery disease; ECG, electrocardiogram.

Modified from Swap CJ, Nagurney JT: Value and limitations of chest pain history in the evaluation of patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes, JAMA 294:2623-2629, 2005.

TABLE 15-2

VALUE OF SPECIFIC COMPONENTS OF THE CHEST PAIN HISTORY FOR THE DIAGNOSIS OF ACUTE MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION (AMI)

AMI, Acute myocardial infarction; CI, confidence interval.

Modified from Swap CJ, Nagurney JT: Value and limitations of chest pain history in the evaluation of patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes, JAMA 294:2623-2629, 2005.

Quality and characteristics of chest discomfort: Patients who describe a chest tightness or pressure are more likely to have angina. Pain that is stabbing, pleuritic, positional, or reproducible is less likely to be angina and is often categorized as atypical chest pain, although the presence of such symptoms does not 100% rule out that the pain may be due to CAD. Although it is generally accepted that a more diffuse area of discomfort is suggestive of angina, whereas a coin-sized, very focal area of discomfort is more likely to be noncardiac, this distinction in itself is not enough to confidently dismiss very focal pain as noncardiac. The severity of the pain or discomfort is not helpful in distinguishing angina from other causes of chest pain. Chest pain that is sudden in onset and maximal intensity at onset is suggestive of aortic dissection. Patients with aortic dissection may describe the pain as tearing or ripping and may describe pain radiating to the back. The Levine sign (pronounced “la vine,” and no relationship to this book’s editor) is when the patient spontaneously clenches his or her fist and puts it over the chest while describing the chest discomfort.

Quality and characteristics of chest discomfort: Patients who describe a chest tightness or pressure are more likely to have angina. Pain that is stabbing, pleuritic, positional, or reproducible is less likely to be angina and is often categorized as atypical chest pain, although the presence of such symptoms does not 100% rule out that the pain may be due to CAD. Although it is generally accepted that a more diffuse area of discomfort is suggestive of angina, whereas a coin-sized, very focal area of discomfort is more likely to be noncardiac, this distinction in itself is not enough to confidently dismiss very focal pain as noncardiac. The severity of the pain or discomfort is not helpful in distinguishing angina from other causes of chest pain. Chest pain that is sudden in onset and maximal intensity at onset is suggestive of aortic dissection. Patients with aortic dissection may describe the pain as tearing or ripping and may describe pain radiating to the back. The Levine sign (pronounced “la vine,” and no relationship to this book’s editor) is when the patient spontaneously clenches his or her fist and puts it over the chest while describing the chest discomfort.

Duration of the discomfort: Angina usually lasts on the order of minutes, not seconds or hours (unless the patient is suffering an MI) or days. Typically, patients will describe stable anginal pain as lasting approximately 2 to 10 minutes. Unstable angina pain may last 10 to 30 minutes. Pain that truly lasts just several seconds or greater than 30 minutes is usually not angina, unless the patient is having an acute MI. One has to be careful because some patients will initially describe the pain as lasting seconds when on further questioning it becomes clear it has really lasted minutes. Pain that lasts continuously (not off and on) for a day or days is usually not angina.

Duration of the discomfort: Angina usually lasts on the order of minutes, not seconds or hours (unless the patient is suffering an MI) or days. Typically, patients will describe stable anginal pain as lasting approximately 2 to 10 minutes. Unstable angina pain may last 10 to 30 minutes. Pain that truly lasts just several seconds or greater than 30 minutes is usually not angina, unless the patient is having an acute MI. One has to be careful because some patients will initially describe the pain as lasting seconds when on further questioning it becomes clear it has really lasted minutes. Pain that lasts continuously (not off and on) for a day or days is usually not angina.

Precipitating factors: Because angina results from a mismatch between myocardial oxygen demand and supply, activities that increase myocardial oxygen demand or decrease supply may cause angina. Discomfort that is brought on by exercise or exertion is highly suggestive of angina. Mental stress or anger may not only increase heart rate and blood pressure, but may also lead to coronary artery vasoconstriction, precipitating angina. One has to be careful in not ruling out angina as the cause of the chest discomfort in patients who experience chest discomfort at rest, without precipitation, however, as this may be due to ACS, where the problem is primarily thrombus formation in the coronary artery, leading to decreased myocardial oxygen supply.

Precipitating factors: Because angina results from a mismatch between myocardial oxygen demand and supply, activities that increase myocardial oxygen demand or decrease supply may cause angina. Discomfort that is brought on by exercise or exertion is highly suggestive of angina. Mental stress or anger may not only increase heart rate and blood pressure, but may also lead to coronary artery vasoconstriction, precipitating angina. One has to be careful in not ruling out angina as the cause of the chest discomfort in patients who experience chest discomfort at rest, without precipitation, however, as this may be due to ACS, where the problem is primarily thrombus formation in the coronary artery, leading to decreased myocardial oxygen supply.

Relief with sublingual nitroglycerin (SL NTG) or rest: NTG is a coronary artery vasodilator. While there are some recent studies to the contrary, typically patients who report partial or complete relief of their chest discomfort within 2 to 5 minutes of taking SL NTG are more likely to be experiencing angina as the cause of their chest discomfort. One has to question patients carefully because some will report that the SL NTG decreased their discomfort, but on further questioning one learns that the discomfort only decreased 30 to 60 minutes after taking the SL NTG. Because SL NTG exerts its effect within minutes, this does not necessarily imply that the chest discomfort was relieved by the SL NTG. However, in patients experiencing MI caused by an occluded coronary artery, the fact that the chest discomfort is not relieved with SL NTG does not necessarily make it less likely that the pain is due to CAD. Patients who experience the chest discomfort, but then sit or rest for minutes and the chest discomfort gradually resolves, are more likely to have angina.

Relief with sublingual nitroglycerin (SL NTG) or rest: NTG is a coronary artery vasodilator. While there are some recent studies to the contrary, typically patients who report partial or complete relief of their chest discomfort within 2 to 5 minutes of taking SL NTG are more likely to be experiencing angina as the cause of their chest discomfort. One has to question patients carefully because some will report that the SL NTG decreased their discomfort, but on further questioning one learns that the discomfort only decreased 30 to 60 minutes after taking the SL NTG. Because SL NTG exerts its effect within minutes, this does not necessarily imply that the chest discomfort was relieved by the SL NTG. However, in patients experiencing MI caused by an occluded coronary artery, the fact that the chest discomfort is not relieved with SL NTG does not necessarily make it less likely that the pain is due to CAD. Patients who experience the chest discomfort, but then sit or rest for minutes and the chest discomfort gradually resolves, are more likely to have angina.

Probability of having CAD: In patients with multiple risk factors for CAD or with known CAD, the occurrence of chest pains is more likely to be due to angina.

Probability of having CAD: In patients with multiple risk factors for CAD or with known CAD, the occurrence of chest pains is more likely to be due to angina.

Associated symptoms: The presence of one or more associated symptoms, such as shortness of breathe, diaphoresis, nausea, or radiating pain, increase the likelihood that the discomfort is due to angina.

Associated symptoms: The presence of one or more associated symptoms, such as shortness of breathe, diaphoresis, nausea, or radiating pain, increase the likelihood that the discomfort is due to angina.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities: ST-segment depressions or elevations, or T-wave inversions, increase the likelihood that the discomfort is due to angina. However, the lack of these findings should not rule out angina as a cause of the chest discomfort. The initial ECG has a sensitivity of only 20% to 60% for MI, let alone merely the presence of CAD.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities: ST-segment depressions or elevations, or T-wave inversions, increase the likelihood that the discomfort is due to angina. However, the lack of these findings should not rule out angina as a cause of the chest discomfort. The initial ECG has a sensitivity of only 20% to 60% for MI, let alone merely the presence of CAD.

Troponin elevation: The finding of an elevated troponin level significantly increases the likelihood that the discomfort is due to angina and CAD. However, the lack of an elevated troponin does not rule out angina and CAD as a cause of the discomfort. Further, as discussed earlier, other conditions besides angina can cause an elevated troponin.

Troponin elevation: The finding of an elevated troponin level significantly increases the likelihood that the discomfort is due to angina and CAD. However, the lack of an elevated troponin does not rule out angina and CAD as a cause of the discomfort. Further, as discussed earlier, other conditions besides angina can cause an elevated troponin.

8. If one is still in doubt as to the diagnosis of CAD, should a stress test be obtained?

Yes. Stress testing for diagnostic purposes is best in patients who, after initial evaluation, have an intermediate probability of having CAD. For example, in a patient with a pretest probability of having CAD of 50%, a positive exercise stress test makes the posttest probability of CAD 85%, whereas a negative exercise stress test makes the posttest probability of CAD just 15%. Stress testing may also be used for prognostic purposes. Stress testing is discussed in greater detail in the chapters on exercise stress testing (Chapter 6), nuclear cardiology (Chapter 7), echocardiography (Chapter 5), and magnetic resonance imaging (Chapter 10). Coronary computed tomography (CT) angiography is an emerging alternate form of diagnosis and is discussed in Chapter 9.

9. Are there exceptions to the classic presentations of anginal pain?

10. Who first described angina, and when?

11. What is Prinzmetal angina?

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Alaeddini, J. Angina Pectoris. Available at http://www.emedicine.com.

2. Cohn, J.K., Cohn, P.F. Chest pain. Circulation. 2002;106:530–531.

3. Delehanty, J.M. Cardiac syndrome X: angina pectoris with normal coronary arteries. Available at http://www.utdol.com.

4. Delehanty, J.M. Variant Angina. Available at http://www.utdol.com.

5. Haro, L.H., Decker, W.W., Boie, E.T., et al. Initial approach to the patient who has chest pain. Cardiol Clin. 2006;24:1–17.

6. Higginson, L.A.J., Chest pain. Porter R.S., Kaplan J.L., eds. The Merck Manual Online. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.: Whitehouse Station, N.J., 2012 Available at http://www.merck.com/mmpe Accessed March 27, 2013

7. Lanza, G.A. Cardiac syndrome X: a critical overview and future perspectives. Heart. 2007;93:159–166.

8. Mayer, S., Hillis, L.D. Prinzmetal variant angina. Clin Cardiol. 1998;21:243–246.

9. Meisel, J.L. Diagnostic Approach to Chest Pains in Adults. Available at http://www.utdol.com.

10. Ringstrom, E., Freedman, J. Approach to undifferentiated chest pain in the emergency department: a review of recent medical literature and published practice guidelines. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73:499–505.

11. Swap, C.J., Nagurney, J.T. Value and limitations of chest pain history in the evaluation of patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2005;294:2623–2629.

12. Tanser, P.H., Approach to the cardiac patient. Porter R.S., Kaplan J.L., eds. The Merck Manual Online. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.: Whitehouse Station, NJ, 2012 Available at http://www.merck.com/mmpe Accessed March 27, 2013

13. Warnica, J.W., Angina Pectoris. Porter R.S., Kaplan J.L., eds. The Merck Manual Online. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.: Whitehouse Station, NJ, 2012 Available at http://www.merck.com/mmpe Accessed March 27, 2013