Chapter 21 Chest Pain

Chest pain is a very common symptom, and its severity and etiology will depend, to a large extent, on the clinical circumstances in which it occurs. Chest pain is the most frequent new symptom reported by patients seen in outpatient clinics. Although it is an extremely nonspecific symptom (Box 21-1), it may be the presenting manifestation of a number of conditions, most of which will be relatively benign. Also, in many patients with such pain, a firm diagnosis may never be established. When chest pain is a presenting symptom in the emergency department setting, however, more serious, acute, and potentially life-threatening causes need to be considered. Accordingly, a complaint of chest pain requires thorough and careful investigation.

Box 21-1

Causes of Chest Pain

Cardiac System

Musculoskeletal Conditions

Differential Diagnosis

Myocardial Ischemia

A wide range of disorders other than angina may be the cause of chest pain. These potential alternative diagnoses are summarized in Box 21-2.

Musculoskeletal Pain

Costochondral and chondrosternal articulations are common sites of anterior and anterolateral chest pain. The articulations of the second, third, and fourth ribs are most commonly involved. When accompanied by swelling, redness, and heat, the condition is referred to as Tietze syndrome. Coughing or trauma can dislocate the costochondral junctions (most commonly those of ribs 10 to 12). The pain resulting from intercostal neuritis most frequently results from cervical osteoarthritis. Intercostal neuritis also is seen with herpes zoster infection, in which the onset of pain may precede the typical rash by 1 or 2 days (Figure 21-1). Thoracic roots most commonly are involved.

Subacromial bursitis, biceps or deltoid tendinitis, and arthritis of the shoulder can manifest as chest pain with extension to the shoulder and arm. The brachial plexus and subclavian artery can be compressed by a cervical rib, or by spasm of the scalenus anticus muscle. In the Pancoast syndrome (most commonly but not exclusively caused by bronchogenic carcinoma), invasion of the C8, T1, and T2 nerve roots by tumor may be the cause of considerable pain and other symptoms such as muscular weakness (Figure 21-2).

Patient Evaluation

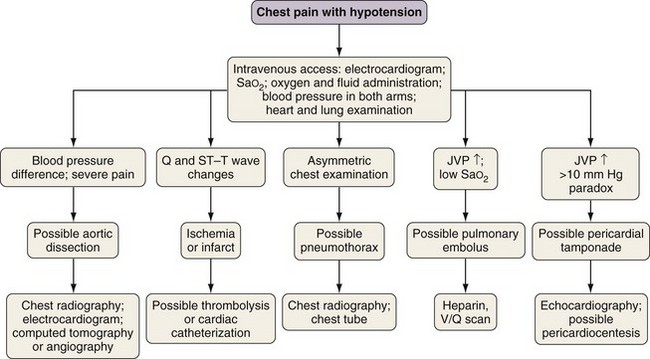

The approach to patients complaining of chest pain should focus initially on the potentially lethal causes of the symptom, especially in the emergency department or similar setting (Figure 21-3). Severe pain is more commonly associated with life-threatening causes, but any of these conditions may occur with minimal symptoms. Accordingly, patients frequently are treated as if the chest pain were life-threatening until these more serious conditions can be excluded by studies that yield more specific information than that obtainable at the time of the initial presentation.

Clinical Presentation

If the pain is acute (and therefore generally of short duration) and the patient is hypotensive, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, pericardial tamponade, dissecting aneurysm, and tension pneumothorax should be considered first (see Figure 21-3). Less commonly, this clinical syndrome can result from a ruptured esophagus, which not infrequently is missed because it is rare and the emergency physician may be reassured by normal findings on cardiac evaluation. In other patients, the approach is governed primarily by the findings on history and physical examination, which are interpreted on the basis of actual or estimated previous probabilities for each of the conditions listed in Box 21-1. For example, a middle-aged man with one or more risk factors for coronary artery disease (e.g., hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, smoking) who experiences exertional chest pain typical for coronary artery disease that abates with rest has a greater than 90% probability of having myocardial ischemia as the cause of his symptoms. By contrast, a 20-year-old pregnant woman with a chest infection, cough, and localized chest pain is far more likely to have a spontaneous rib fracture.

History

Pulmonary Inflammation and Chest Wall Problems

An abrupt onset suggests a rib fracture, pneumothorax, or pneumomediastinum (Figure 21-4). A more gradual onset over a few minutes or hours is seen with bacterial pneumonia and pulmonary emboli, and a gradual onset (e.g., days or weeks) is more compatible with chronic infections (e.g., tuberculosis, fungal infections) or tumor.

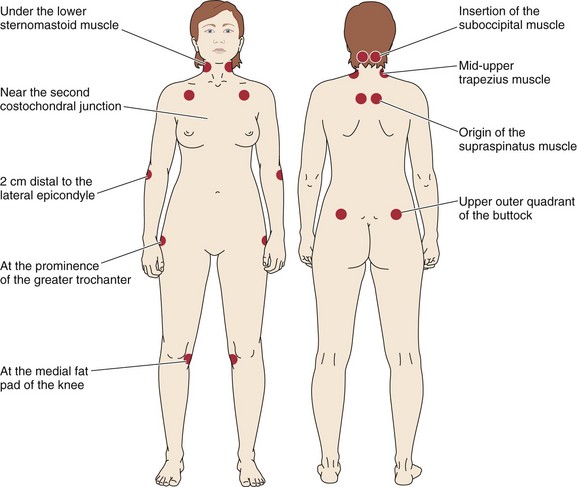

In many instances, patients with costochondral pain or pain that results from muscle strains describe an episode of chest trauma or unusual upper extremity exercise (e.g., gardening, digging, scraping) that can result in an overuse syndrome. More commonly, no specific inciting event can be determined. The costosternal articulations are common “trigger sites” for the pain of fibromyalgia. Patients with this syndrome also have trigger sites in other locations (Figure 21-5). Musculoskeletal conditions generally are exacerbated by deep breathing and frequently are overlooked as causes of pleuritic or exercise-induced chest pain. The patient often can localize the painful area, where tenderness or muscular spasm may be elicited by palpation.

Gastrointestinal Disorders

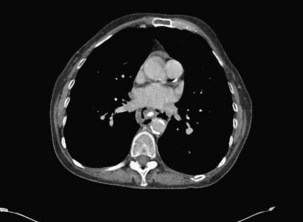

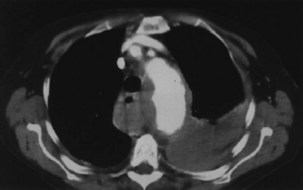

Esophageal rupture is a life-threatening condition if not recognized rapidly and repaired. It can occur in otherwise healthy persons, in whom it may follow an episode of choking while swallowing, or violent or prolonged vomiting. It usually is accompanied by a distinct acute central episode of chest pain, sweating, and then hypotensive symptoms, with onset of pleuritic pain as gastric fluid leaks into the chest cavity. Dysphagia also may be pronounced. A CT scan with a contrast swallow can be diagnostic, showing air to have leaked into the mediastinum (Figure 21-6).

Physical Examination

Intercostal neuritis frequently is associated with hyperalgesia or anesthesia over the distribution of affected intercostal nerves. Biliary colic and pancreatitis frequently are associated with right upper quadrant and midline abdominal tenderness, respectively. Clearly, it is vital not to miss important physical disease in the chest wall. Careful, gentle palpation with both hands over the skin, musculature, ribs, and vertebrae may identify tender areas that signify a serious problem (Figure 21-7, A and B).

Diagnostic Tests

Patients without a previous diagnosis of coronary artery disease are not likely to have an acute myocardial infarction as the explanation for the acute onset of chest pain if the pain does not radiate to the neck, left shoulder, or arm and if the electrocardiogram and serial serum troponin levels are normal. Although the finding of flat or downsloping ST segment depression greater than 0.1 mV increases the likelihood that an episode of chest pain is caused by myocardial ischemia, the tracing may be normal at rest, between attacks, or even in the presence of active ischemia. Up to 80% of patients with coronary disease exhibit these ST segment changes during exercise, but such changes also may be found in up to 15% of patients with no evidence of disease at cardiac catheterization. Nonspecific ST-T wave changes have been documented in the setting of acute cholecystitis and esophageal spasm, as well as in other conditions for which chest pain is a presenting symptom (Table 21-1).

Table 21-1 Electrocardiographic Findings in Conditions Manifesting with Chest Pain

| Condition | Electrocardiographic Finding(s) |

|---|---|

| Acute cholecystitis | Inferior ST segment elevation |

| Pulmonary embolism | Inferior ST segment elevation |

| Dissecting aortic aneurysm | ST segment elevation |

| ST segment depression | |

| Pneumothorax | Poor R wave progression |

| Acute QRS axis shift | |

| Pericarditis | ST segment elevation (generally diffuse) |

| Myocarditis | ST segment elevation |

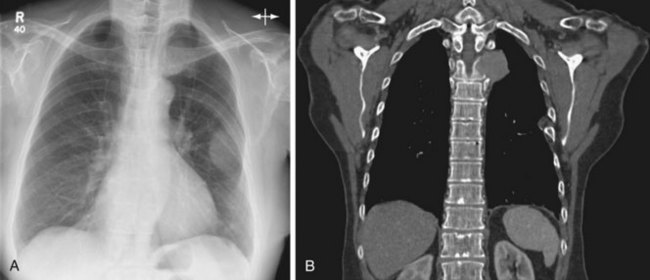

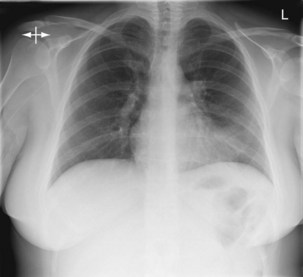

Chest radiographs may be normal-appearing in the setting of acute pulmonary emboli, although minor degrees of atelectasis, small effusions, or distention of the central pulmonary vessels may be seen. A small or an apical pneumothorax can be difficult to see, but if this lesion is suspected, a film exposed with the patient in full expiration will make it much larger and obvious. Careful radiographic review of all ribs should identify a fracture, most commonly located in the lower ribs if due to coughing. Local rib tenderness always warrants a chest radiograph (Figure 21-8). Anatomic anomalies such as a cervical rib, which may be the cause of root pain, should be looked for as appropriate. If pleuritic pain is associated with minor change, such as the obliteration of a costophrenic angle, obtaining a follow-up radiograph 24 hours later may show obvious development of the cause of chest pain. Pericardial causes of pain will become evident only if an effusion is gathering by causing the cardiac outline to enlarge; an effusion also may be a sign of malignant disease elsewhere within the chest, or of joint disease in connective tissue disorders.

A widened mediastinum or an apical effusion on films exposed with the patient in the supine position (Figure 21-9) suggests the possibility of a ruptured aortic aneurysm.

Atar S, Barbagelata A, Birnbaum Y. Electrocardiographic diagnosis of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiol Clin. 2006;24:343–365.

Cayley WEJr. Diagnosing the cause of chest pain. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:2012–2021.

Eiseneman A. Troponin assays for the diagnosis of myocardial infarction and acute coronary syndrome: where do we stand? Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2006;4:509–514.

Fletcher GF, Mills WX, Taylor WC. Update on exercise stress testing. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1749–1754.

Fox M, Forgacs I. Unexplained (non-cardiac) chest pain. Clin Med. 2006;6:445–449.

Haro LH, Decker WW, Boie ET, Wright RS. Initial approach to the patient who has chest pain. Cardiol Clin. 2006;24:1–17.

Jones JH, Weir WB. Cocaine-induced chest pain. Clin Lab Med. 2006;26:127–146.

Schoepf UJ, Savino G, Lake DR, et al. The age of CT pulmonary angiography. J Thorac Imaging. 2005;20:273–279.

Tutuian R. Update in the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastrointest Liver Dis. 2006;15:243–247.

Winters ME, Katzen SM. Identifying chest pain emergencies in the primary care setting. Primary Care. 2006;33:625–642.