Chest Pain

Perspective

Approximately 6 million patients visit the emergency department (ED) each year with complaints of chest pain, constituting 9% of all patients seen in EDs in the United States.1 Over the last 10 years, the total number of ED patients with noninjury complaints increased by 22%, whereas the percentage of patients with chest pain decreased slightly.2 Chest pain is a symptom caused by several life-threatening diseases and has a broad differential diagnosis. It is complicated by a frequent disassociation between intensity of symptoms and signs and seriousness of underlying pathology.

Diagnostic Approach

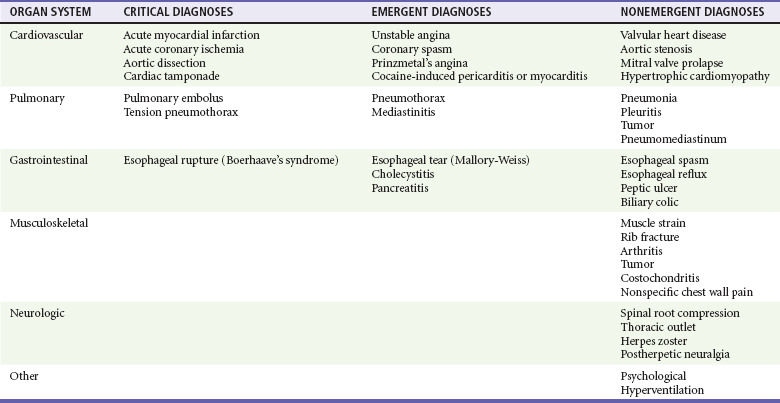

Because of the indistinct nature of visceral pain, the differential diagnosis of chest pain is broad and includes many of the most critical diagnoses in medicine and many nonemergent conditions (Table 26-1).

Rapid Stabilization and Assessment

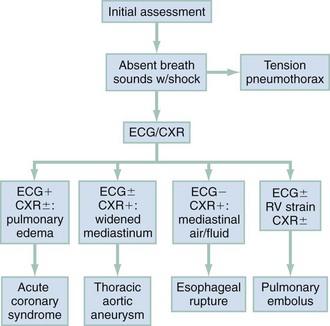

In clinical evaluation of the patient, the initial questions are “Should I intervene immediately?” and “What are the life-threatening possibilities in this patient?” The answers are usually apparent within the first few minutes after assessment of the patient’s appearance, ECG, and vital signs. If a patient has unilateral chest pain, respiratory distress, shock, and unilateral reduction or absence of breath sounds, immediate intervention with needle or tube thoracostomy is required. In addition, patients with severe derangements in vital signs require stabilizing treatment during a search for the precipitating cause. Patients with respiratory distress require immediate intervention and lead the emergency physician to consider a more serious cause of the pain (Fig. 26-1; also see Chapter 25).

Symptomatic derangements in vital signs are addressed. If vital signs are stable, a focused history and physical examination are performed. Most patients also require a chest radiograph to evaluate the chest pain. If myocardial ischemia is suspected, aspirin and nitroglycerin may be appropriate. Patients with pain and findings suggestive of aortic dissection and with significant hypertension are candidates for immediate reduction of blood pressure (see Chapter 85). Patients with low voltage on the ECG, diffuse ST segment elevation, elevated jugular venous pressure on examination,3 and signs of shock should undergo prompt bedside cardiac ultrasound.

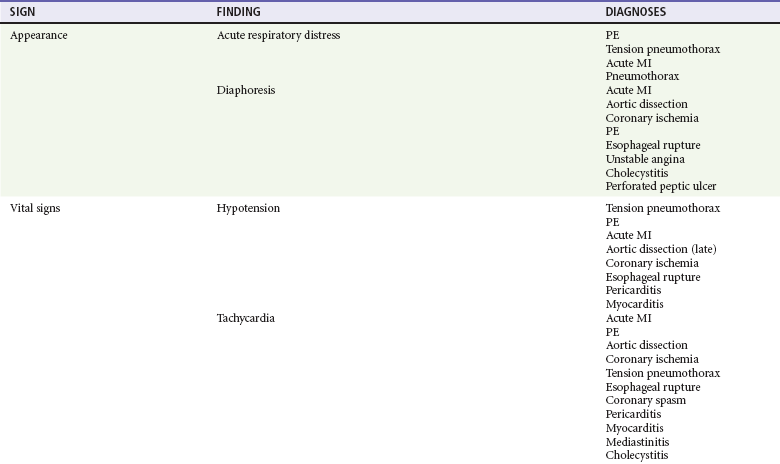

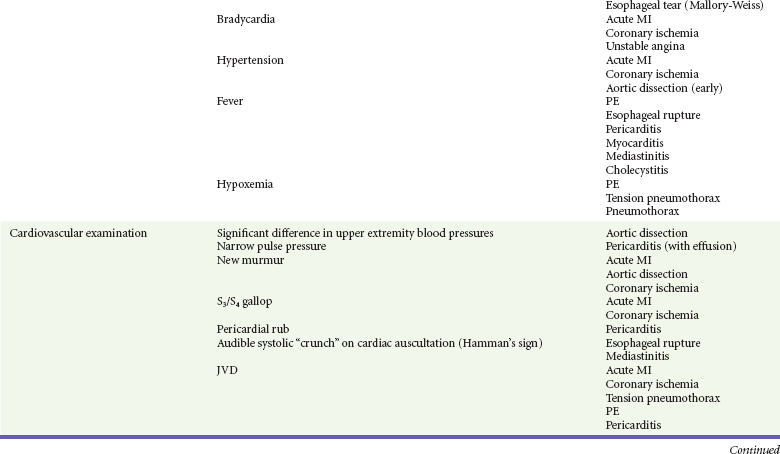

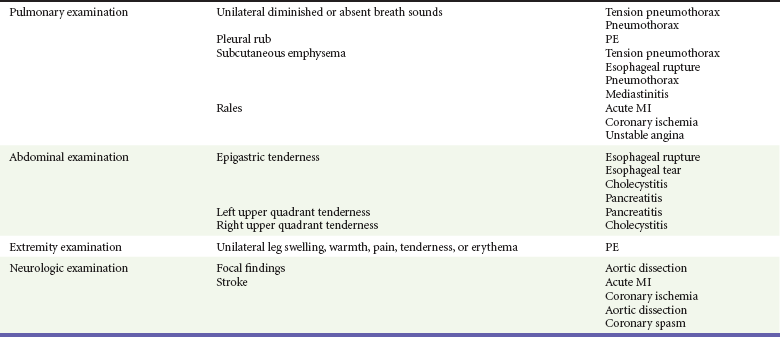

Pivotal Findings

History

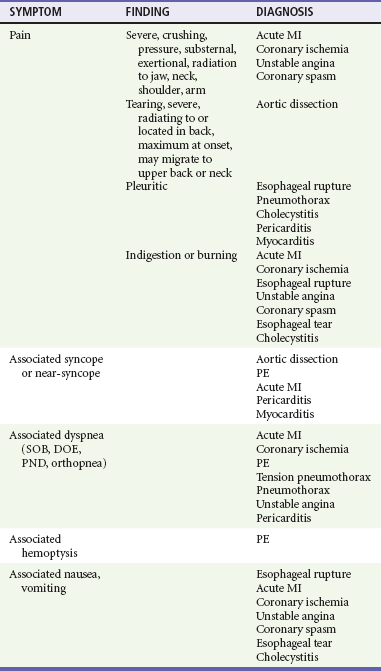

1. The patient is asked to describe the character of the pain or discomfort. Descriptions such as “squeezing,” “crushing,” or “pressure” lead the emergency physician to suspect a cardiac ischemic syndrome, although cardiac ischemia can also be characterized by nonspecific discomfort, such as “bloating” or “indigestion.” “Tearing” pain that may migrate from the front to back or back to front is the classic description in aortic dissection. “Sharp” or “stabbing” pain is seen more in pulmonary and musculoskeletal diagnoses. Patients reporting a “burning” or “indigestion” type of pain may initially be thought to have a gastrointestinal condition, but owing to the visceral nature of chest pain, patients with all causes of pain may use any of the preceding descriptions. Of note, descriptors may vary among ethnic groups, and, for example, “sharp” may mean “severe.”

2. Additional history about the patient’s activity at the onset of pain may be helpful. Pain occurring during exertion suggests an ischemic coronary syndrome, whereas progressive onset of pain at rest suggests acute MI. Pain of sudden onset is more typical with aortic dissection, PE, or pneumothorax. Pain after meals is more indicative of a gastrointestinal cause.

3. The severity of pain is commonly quantified with a 1-to-10 pain scale. Alterations in pain severity are documented at times of onset, peak, present, and after intervention.

4. The location of the discomfort is described. Pain that is localized to a small area is more likely to be somatic versus visceral in origin. Pain localized at the periphery of the chest is more likely to have a pulmonary rather than a cardiac cause. Lower chest or upper abdominal pain may be of cardiac or gastrointestinal origin.

5. Any description of radiation of pain should be noted. Transthoracic pain through to the back should suggest aortic dissection or gastrointestinal causes, especially pancreatitis or posterior ulcer. Inferoposterior myocardial ischemia may also manifest primarily as thoracic back pain. Radiation to the arms, neck, or jaw increases the likelihood of cardiac ischemia.4,5 Pain located primarily in the back, especially interscapular back pain that migrates to the base of the neck, suggests aortic dissection.6

6. Duration of pain is another important historical factor. Pain that lasts a few seconds or minutes is rarely of cardiac origin.7 Pain that is exertional but abates with a few minutes of rest may be a manifestation of cardiac ischemia.4 Pain that is maximal at onset may be caused by aortic dissection.6 Pain that is not severe and persists over the course of days is less likely to be of serious origin than pain that is severe or has a stuttering or fluctuating course.

7. The clinician should consider aggravating or alleviating factors. Pain that worsens with exertion and improves with rest is more likely related to coronary ischemia.4 Pain related to meals is more suggestive of a gastrointestinal cause. Pain that worsens with respiration is seen more often with pulmonary, pericardial, and musculoskeletal causes.

8. Other associated symptoms may suggest the visceral nature of the pain (Table 26-2). Diaphoresis should lead to an increased clinical suspicion for a serious or visceral cause. Hemoptysis, a classic PE sign, is rarely seen.8 Near-syncope and syncope lead to higher likelihood of a cardiovascular cause or PE. Dyspnea is seen in cardiovascular and pulmonary disease. Nausea and vomiting may be seen in cardiovascular and gastrointestinal complaints.

9. A history of prior pain and the diagnosis of that episode can facilitate the diagnostic process, but the physician should be wary of prior presumptive diagnoses that may be misleading. A prior history of cardiac testing, such as stress testing, echocardiography, or angiography, may be useful in determining if the current episode is suggestive of cardiac disease. Similarly, patients with previous spontaneous pneumothorax or PE9 are at increased risk of recurrence.

10. The presence of risk factors for a particular disease is primarily of value as an epidemiologic marker for large population studies (Box 26-1). In the ED, presence of risk factors in an individual patient without established disease has minimal or no effect on the clinical likelihood (pretest probability) of a specific disease process.

Ancillary Studies

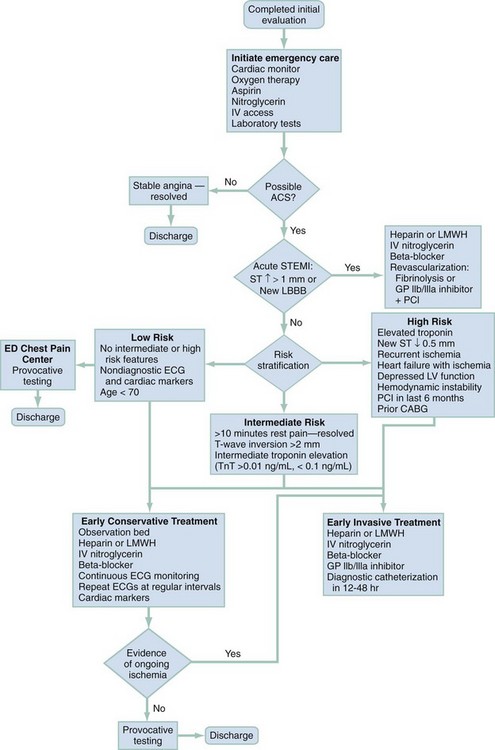

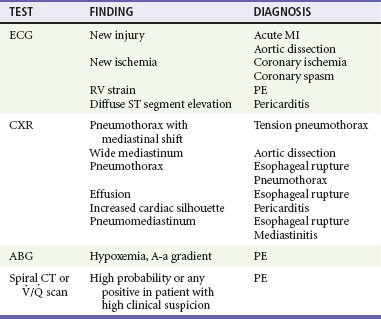

The two most commonly performed studies in patients with chest pain are the chest radiograph and 12-lead ECG (Table 26-4). An ECG should be performed within 10 minutes of arrival in all patients with chest pain in whom myocardial ischemia is a possibility.10,11 This generally includes all male patients 33 years old and older and female patients older than 39 who report pain from the umbilicus to the mandible unless a noncardiac cause is readily apparent. Rapid acquisition of the ECG facilitates the diagnosis of acute MI and expedites the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s recommended “door to treatment” times from arrival to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or thrombolytic therapy in acute MI. Patients with a new injury pattern on ECG (Table 26-5) or new ischemic ECG changes should have appropriate therapy instituted at this point (Fig. 26-2; see also Chapter 78). An ECG showing right ventricular strain pattern, in the appropriate setting, should raise the clinical suspicion for PE. Diffuse ST segment elevation helps make the diagnosis of pericarditis.

Table 26-5

Electrocardiogram Findings in Ischemic Chest Pain

| Classic myocardial infarction | ST segment elevation (>1 mm) in contiguous leads; new LBBB |

| Q waves >0.04 sec duration | |

| Subendocardial infarction | T wave inversion or ST segment depression in concordant leads |

| Unstable angina | Most often normal or nonspecific changes; may see T wave inversion |

| Pericarditis | Diffuse ST segment elevation; PR segment depression |

Pneumomediastinum is seen with esophageal rupture and mediastinitis. A serum D-dimer assay may help discriminate patients with PE from those with a possible gastrointestinal cause. A low serum D-dimer in a patient without a high pretest probability of PE effectively excludes the diagnosis.8,12,13 Patients with low pretest probability who meet certain defined criteria do not require further testing (see Chapter 88).14

Patients at high pretest probability for PE should undergo diagnostic imaging (multidetector computed tomography [CT] or, far less commonly, pulmonary angiography or a ventilation-perfusion lung scan).15 High pretest probability warrants initiation of anticoagulation (heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin) therapy in the ED before the imaging study, in the absence of a contraindication.

Patients with suspected thoracic aortic dissection may be evaluated by CT angiography, transesophageal echocardiography, or magnetic resonance imaging. Selection of imaging modality depends on patient status and availability of the testing.16

CT with a 64 or higher detector scanner has the potential to rule out all of the life-threatening causes of chest pain. Although ACS, PE, and thoracic dissection (the “triple rule out”) are the causes most commonly discussed, pneumothorax, mediastinitis, and pericardial effusions are also diagnosed with CT.17,18

Laboratory testing is useful in the evaluation of ACS. Creatine kinase (CK) is associated with multiple false-positive results and has no use in the evaluation of unstable angina. CK-MB, an isoform of CK, is more specific for cardiac ischemia but largely has been supplanted by troponin testing. CK-MB produces fewer false-positive results than CK, and peak sensitivity approaches 98%. Sensitivity at 4 hours is, however, only about 60%. CK-MB isoforms improve sensitivity at 4 hours to 80%, approaching 93% at 6 hours. The current universal definition of MI places CK and CK-MB in a secondary role to troponins.19

Troponins (I and T), when elevated, identify patients with ACS who have the highest risk for an adverse outcome.19,20 Sensitivity for acute MI at 4 hours is 60%, rising to nearly 100% by 12 hours.21,22 Elevated troponin in the correct clinical setting is synonymous with acute MI and is embedded in the universal definition of MI.19

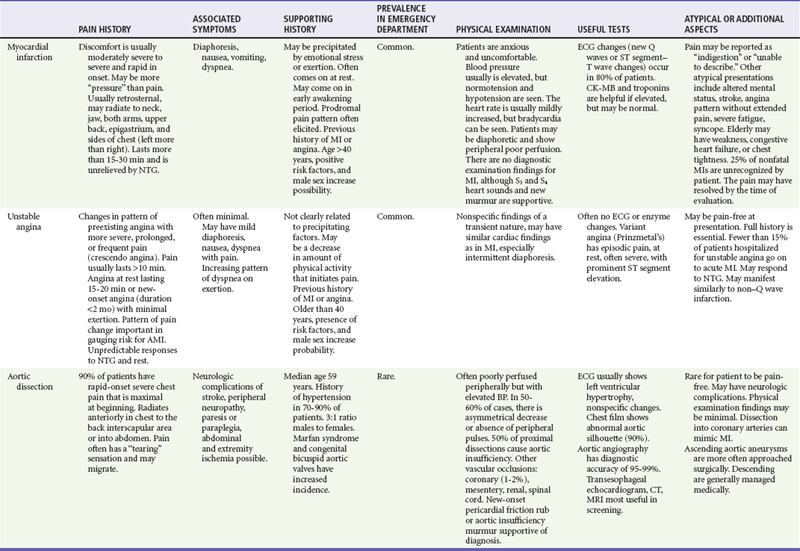

Diagnostic Table

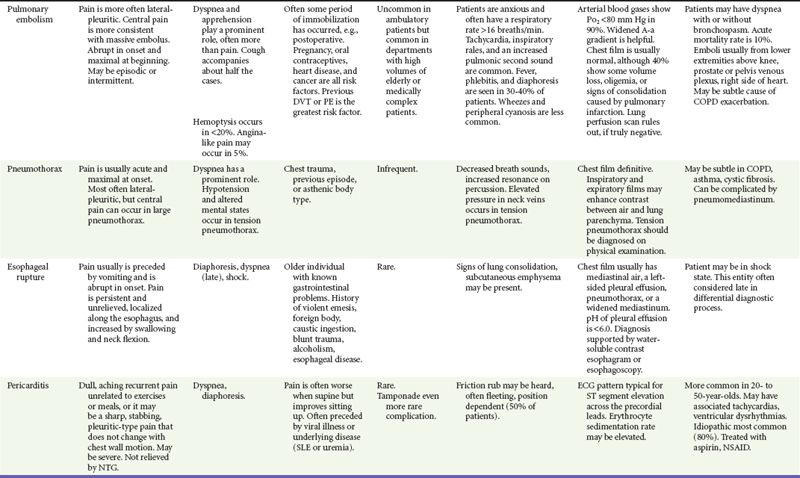

After the patient is stabilized and assessment is completed, the findings are matched to the classic and atypical patterns of the seven potentially critical diseases causing chest pain. This matching process is continual while the patient is evaluated and the response to therapy is monitored. Any inconsistency in findings with the primary working diagnoses requires a rapid review of the pivotal findings and the potential diagnoses (Table 26-6).

Table 26-6

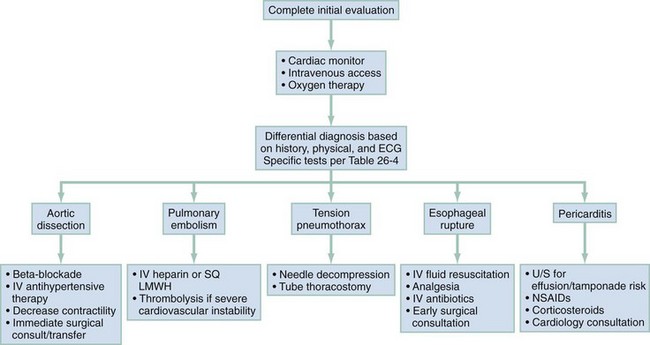

Management and Disposition

The management of ACS is discussed in Chapter 78. Figure 26-3 outlines the approach to treatment of critical noncardiac diagnoses. Patients with critical diagnoses generally are admitted to the intensive care unit. Patients with emergent diagnoses typically are admitted to the hospital, most often on telemetry units. Patients with nonemergent diagnoses are most frequently treated as outpatients. Hospitalization is required in certain circumstances, particularly when patients have other comorbid conditions.

References

1. Niska, R, Bhuiya, F, Xu, J, 2007 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Report. 2010;(26):1.

2. Bhuiya, F, Pitts, S, McCaig, L, Emergency department visits for chest pain and abdominal pain: United States, 1999-2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2010;(43):1.

3. McGee, SR. Evidence-Based Physical Diagnosis. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2001.

4. Goodacre, S, Locker, T, Morris, F, Campbell, S. How useful are clinical features in the diagnosis of acute, undifferentiated chest pain? Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:203.

5. Panju, AA, Hemmelgarn, BR, Guyatt, GH, Simel, DL. The rational clinical examination. Is this patient having a myocardial infarction? JAMA. 1998;280:1256.

6. Klompas, M. Does this patient have an acute thoracic aortic dissection? JAMA. 2002;287:2262.

7. Lee, TH, et al. Acute chest pain in the emergency room. Identification and examination of low-risk patients. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:65.

8. Kline, JA, Wells, PS. Methodology for a rapid protocol to rule out pulmonary embolism in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:266.

9. Eichinger, S, et al. Symptomatic pulmonary embolism and the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:92.

10. Antman, EM, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction—executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction). Circulation. 2004;110:588.

11. Diercks, DB, et al. Door-to-ECG time in patients with chest pain presenting to the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:1.

12. American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Committee; Clinical Policies Committee Subcommittee on Suspected Pulmonary Embolism. Clinical policy: Critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting with suspected pulmonary embolism. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:257.

13. Wells, PS, et al. Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: Management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and d-dimer. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:98.

14. Kline, JA, et al. Prospective multicenter evaluation of the pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:772.

15. Stein, PD, et al. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2317.

16. Shiga, T, Wajima, Z, Apfel, CC, Inoue, T, Ohe, Y. Diagnostic accuracy of transesophageal echocardiography, helical computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging for suspected thoracic aortic dissection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1350.

17. Limkakeng, AT, Halpern, E, Takakuwa, KM. Sixty-four slice multidetector computed tomography: The future of ED cardiac care. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:450.

18. Rubinshtein, R, et al. Usefulness of 64-slice cardiac computed tomographic angiography for diagnosing acute coronary syndromes and predicting clinical outcome in emergency department patients with chest pain of uncertain origin. Circulation. 2007;115:1762.

19. Thygesen, K, Alpert, JS, White, HD, Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Universal definition of the myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116:2634.

20. Ohman, EM, et al. Cardiac troponin T levels for risk stratification in acute myocardial ischemia. GUSTO IIA Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1333.

21. Fesmire, FM, et al. Clinical policy: Critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients with non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:270.

22. Morrow, DA, et al. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory Medicine practice guidelines: Clinical characteristics and utilization of biochemical markers in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2007;115:e356.

, ventilation-perfusion.

, ventilation-perfusion.