Chapter 3 Chest pain

Introduction

Chest pain is the commonest reason for 999 calls and accounts for 2.5% of out-of-hours calls. Of patients taken to hospital, about 10% will have an acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Evidence suggests that up to 7.5% of these will be missed on first presentation. There are a number of other life threatening conditions which can present as chest pain and must not be overlooked. The objectives of this article are therefore to provide a safe and comprehensive system of dealing with this presenting complaint (Box 3.1).

Box 3.1 Objectives of assessment of patients with chest pain

To identify any patients who have a normal primary survey but have an obvious need for hospital admission

To identify any patients who have a normal primary survey but have an obvious need for hospital admission To undertake a secondary survey considering other systems of the body where dysfunction could present as chest pain

To undertake a secondary survey considering other systems of the body where dysfunction could present as chest painPrimary survey

Follow the ABC principles (Box 3.2).

Patients with normal primary survey with obvious need for hospital admission

There are three immediately life threatening medical conditions that can present with chest pain:

Fifty percent of sudden cardiac deaths occur within 1 hour of the start of a myocardial infarction and 75% within 3 hours. The benefits of thrombolysis or percutaneous intervention (PCI) are directly related to the length of time between the onset of symptoms and its delivery. Therefore if you diagnose a myocardial infarction, ensure you have immediate access to a defibrillator and consider thrombolysis or arrange rapid transportation to a facility where thrombolysis or PCI can be delivered.

Secondary survey (including history taking)

Take a history of the presenting complaint, gather relevant information, and perform an examination (see Chapter 2).

The OPQRST of chest pain

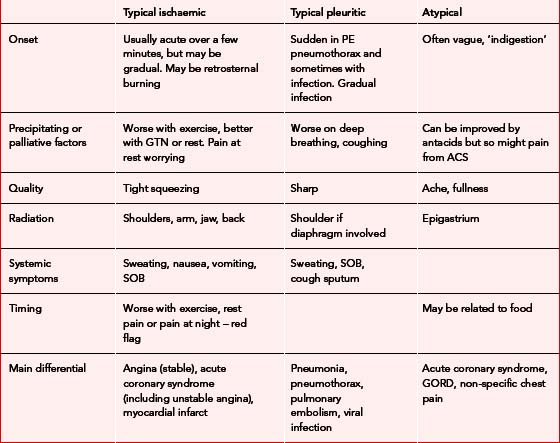

Chest pain is often categorised into three main types (Table 3.1). It can be very difficult to place any particular patient into one of these categories, but there is evidence that the characteristics of pain can help in the diagnosis:

Onset of pain

The pain of a myocardial infarction is classically described as rapidly increasing over a few minutes but it can develop gradually or even be intermittent. In an acute coronary syndrome the pain may well be intermittent. As the platelet thrombus breaks down, blood flow is restored and the pain is relieved. Beware of pain starting at rest, or that which wakes the patient up from sleep.

Precipitating factors/palliative factors

Gain a detailed impression of how the pain started. Establish if there is any relation to exercise, breathing or food. Pain that has been provoked by exercise or wakened the patient should be regarded as significant. GTN will improve angina pain but also will improve pain from oesophageal problems. Equally there is no evidence that improvement of pain after giving an antacid can help distinguish between cardiac and oesophageal pain.

Other factors

Risk factors

The presence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease should increase your suspicion as to a cardiac cause for the pain (Box 3.3).

Medical history/drugs allergies

It is important during the history taking to ask the patient about their medical history as they may already have had an illness that could present as chest pain. A drug history is also important; specifically ask about aspirin (you may need to give this), and if they have taken GTN, warfarin, or other cardiac medications.

TIMI scoring

TIMI risk scoring is one method of assessing the risk of a patient of having a significant cardiac event (MI, death, need for revascularisation) within the next 2 weeks. It assesses seven variables listed in Box 3.4. Cardiac markers are not routinely available at present in the community setting. If a patient has no or only one point the risk of an event is 4.7% (note even this is an appreciable risk). If they have 6 points the risk is 40%. While TIMI scoring can be used to guide therapy in the hospital setting it should not be used to ‘rule out’ ischaemic heart disease in the community setting.

Social history and substances

Some illegal drugs such as cocaine may cause chest pain. Patients with a history of alcohol misuse or illegal drug use are at increased risk of developing chest infections and suffering from thromboembolic disease.

Vital signs

Unless you are transporting the patient immediately, always measure a full set of vital signs.

Differential diagnosis

Table 3.2 shows a list of the differential diagnoses classified by the type of pain they present with.

| Cardiac ischaemic pain | Pleuritic pain | Atypical pain |

|---|---|---|

| Angina | Pneumonia | Non-specific chest pain |

| Acute coronary syndrome | Pulmonary embolism | Oesophageal pain |

| (Dissecting aortic aneurysm) | Pneumothorax | Cardiac pain |

| (Oesophageal pain) | Rib injury | Gastric/biliary pain |

| (Pericarditis) | (Pericarditis) | Chest wall pain |

| Pericarditis | ||

| Dissecting aortic aneurysm |

Cardiac pain

Ischaemic cardiac pain originates from the myocardium when its blood supply is insufficient for its needs. It can be broadly divided into two categories – angina and acute coronary syndrome.

Chest pain

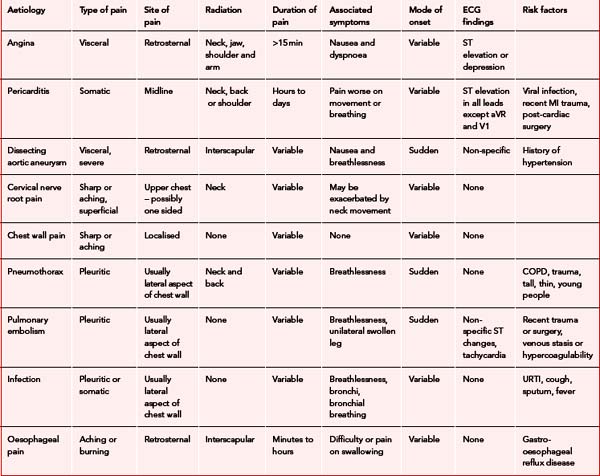

Table 3.3 provides a summary of causes and types of chest pain.

Angina

Consider this diagnosis if the pain lasted less than 15 minutes or settles within 5 minutes of GTN administration and is a single episode. If it occurs at rest or is more severe than the patient’s usual angina, consider it to be acute coronary syndrome and refer. If the patient is young (35–70) and this is the first episode of typical ischaemic pain and has come on at rest, refer even with one episode.

Myocardial infarction

Carry out a full ABC assessment and provide oxygen and analgesia (appropriate to the diagnosis). A defibrillator must be taken to any patient complaining of chest pain. See Box 3.5 for the management of MI.

Pericarditis

The pericardium is a double layer of tissue, which envelops the heart. It has an outer thick, fibrous layer that is attached to the base of the great vessels and the diaphragm. The gap between the heart and this fibrous layer is called the pericardial space. This is covered by a thin, serous layer, which lines the inner surface of the fibrous pericardium as well as the outer surface of the heart. Normally the two serous layers slide over one another during the movement of the heart, an action facilitated by the small amount of fluid in pericardial space. However, in pericarditis the surfaces become swollen, tender and inflamed. This usually results from infection but it can result from autoimmune reactions, after myocardial infarction and cardiac surgery. Pericarditis commonly presents as chest pain described as midline and sharp. The pain is made worse by movement and breathing, whereas sitting up and leaning forward may relieve it. The pain may radiate to the back, neck or left shoulder and is associated with dyspnoea, tiredness and fever.

Chest wall pain

This is pain originating from the ribs or chest wall musculature, or both. It may be related to trauma, in which case the area of tenderness is at the site of injury. In non-trauma cases, the pain and tenderness are usually over the anterior chest wall. Treatment is with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. If associated with major trauma, patients should be admitted.

Pulmonary embolism

Risk factors include intravenous drug abuse, a recent history of trauma or surgery, venous stasis or hypercoagulability. The pre-test probability of a pulmonary embolism can be predicted from Table 3.4.

Table 3.4 Pre-test probability of pulmonary embolism well’s criteria

| Factor | Risk score |

|---|---|

| Clinical signs of DVT | 3.0 |

| Other diagnosis less likely | 3.0 |

| HR >100 | 1.5 |

| Stasis or operation in <4/52 | 1.5 |

| History of DVT or PE | 1.5 |

| Active Ca or treatment in <6/12 | 1.0 |

| Haemoptysis | 1.0 |

Low risk 2 or less; moderate risk 2–6; high risk > 6.

Infection

The patient may have a history of a current or recent upper respiratory tract infection and a productive cough. On examination there may also be fever and breathlessness. To make decisions on treatment and whether the patient can be left at home, the following guidelines from the British Thoracic Society should be used – admit if:

Treatment and disposal

Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernick PJ LM, et al. The TIMI Risk Score for unstable angina/non ST elevation MI. JAMA. 2000;284:835-842.

Klompas M. Does this patient have an acute thoracic aortic dissection? JAMA. 2002;287:2262-2272.

Panju AA, Hemmelgarn BR, Guyatt GH, et al. Is this patient having a myocardial infarction? JAMA. 1998;280:1256-1263.

Swap CJ, Nagurney JT. Value and limitations of chest pain history in the evaluation of patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2005;294:2623-2629.

Channer K, Morris F. ABC of clinical electrocardiography: myocardial ischaemia. BMJ. 2002;324:1023-1036. Available online: http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/content/full/324/7344/1023?eaf (5 Mar 2007)

Foster B. 12-Lead electrocardiography for ACLS providers. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1996.

Meek S, Morris F. ABC of clinical electrocardiography: introduction. I – Leads, rate, rhythm, and cardiac axis. BMJ. 2002;324:415-418. Available online: http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/content/full/324/7334/415 (5 Mar 2007)

Meek S, Morris F. ABC of clinical electrocardiography: introduction. II – Basic terminology. BMJ. 2002;324:470-473. Available online: http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/content/full/324/7335/470?eaf (5 Mar 2007)

Meek S, Morris F. ABC of clinical electrocardiography: acute myocardial infarction – part II. BMJ. 2002;324:963-966. Available online: http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/content/full/324/7343/963?eaf (5 Mar 2007)

Morris F, Brady WJ. ABC of clinical electrocardiography: acute myocardial infarction – Part I. BMJ. 2002;324:831-834. Available online: http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/content/full/324/7341/831?eaf (5 Mar 2007)

Boehringer Ingelheim. Thrombolysis up front version 2.2, May 2003. Bracknell: Boehringer Ingelheim, 2003.

British Thoracic Society. Guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults. Thorax. 2001;56(suppl 4):1-64.

British Thoracic Society. Guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in childhood. Thorax. 2002;57(suppl 1):1-24.

Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee. Guidelines version 2. London: JRCALC Royal College of Physicians, 2002. Available online: http://www.asancep.org.uk/JRCALC/guidelines.htm (5 Mar 2007)