CHEST INJURY

BROKEN RIBS

Direct force applied to the chest wall can break the ribs, causing extreme pain with breathing, collapse of a lung (pneumothorax), or both. If the right lower ribs are broken, be alert to the possibility of a bruised or cracked liver, which lies directly below; if the left lower ribs are broken, the underlying spleen may be injured.

FLAIL CHEST

If a number of ribs are broken or detached in series, so that the affected section of the chest wall cannot expand and contract in synchrony with the rest of the chest, then a flail chest (Figure 26) is present. Depending on the size of the flail segment, this can cause severe respiratory compromise. Occasionally, the flail segment moves with breathing in a direction opposite to the rest of the chest wall.

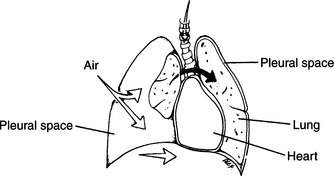

PNEUMOTHORAX

A pneumothorax is a collapsed lung created when there is an air leak (from the lung or from a penetrating wound of the chest wall) into the space between the lung and the inside of the chest wall (pleural space). In the normal situation, the pleural space is undetectable and filled with negative pressure, which allows the lung to expand and contract with chest wall movement (breathing). When air leaks into the pleural space, either from a lung injury or from a hole in the chest wall, the lung collapses. The lung may then be increasingly compressed if air accumulates in the pleural space under pressure (Figure 27). A collapsed lung is recognized by diminished or absent breath sounds (heard through a stethoscope or an ear held against the chest wall) on the affected side, accompanied by chest pain, shortness of breath, and difficult breathing. If air accumulates under pressure in the affected pleural space, this becomes a “tension” pneumothorax. It is characterized by rapidly progressive difficulty in breathing associated with a pneumothorax, cyanosis (blue skin discoloration), distended neck (jugular) veins, and a shift of the windpipe away from the affected side.

Rarely, air that escapes from the lung to create a pneumothorax can become trapped under the skin, creating a “crackling” sensation when the skin is pressed, a sensation of fullness or visible swelling in the neck, a change in voice, and difficulty swallowing. While worrisome in appearance, this subcutaneous (under the skin) air absorbs over time and is not nearly as dangerous as a collapsed lung.

TREATMENT FOR CHEST INJURIES

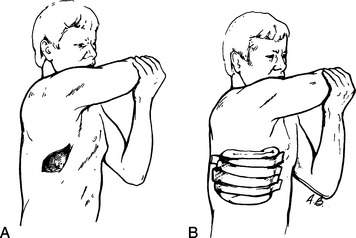

1. Attend to any chest wounds. All open wounds (particularly those in which air is bubbling) should be rapidly covered, to avoid “sucking” chest wounds that could allow more air to enter the pleural space and thus continue to worsen a collapsed lung (see page). For a dressing, a Vaseline-impregnated gauze, heavy cloth, or adhesive tape (Figure 28) can be used. The dressing should be sealed to the chest on at least three sides. If the victim develops a tension pneumothorax following a penetrating wound to the chest and his condition deteriorates rapidly (difficulty breathing, cyanosis, distended neck veins, collapse followed by unconsciousness), force a finger through the wound into the chest to allow the air under pressure to escape. If your diagnosis is correct, you will hear a hissing noise as the air rushes out. This allows the lung to partially expand and may save the victim’s life. After the release of air from a tension pneumothorax, cover the wound with a dressing and seal only three sides to create a flutter-valve effect (air can exit, but not enter) and prevent a recurrence—which might come with a complete seal.

2. Administer oxygen (see page 431). If an oxygen tank is available, oxygen should be administered at a rate of 5 liters per minute by face mask or nasal prongs. Elderly victims who have been heavy cigarette smokers (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]: see page 47) should be watched carefully for signs of decreasing consciousness whenever oxygen is administered. If this occurs (in the absence of head trauma or shock), supplemental oxygen should be discontinued.

3. Assess the rate and adequacy of breathing. Watch for chest rise, feel and listen to the chest, place a hand near the nose and mouth to check for air movement, and observe skin color. If necessary, assist breathing. This may be done with mouth-to-mouth breathing (see page 29) or with a mask device. If the victim is not breathing, check for pulses and assess the need for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) (see page 32).

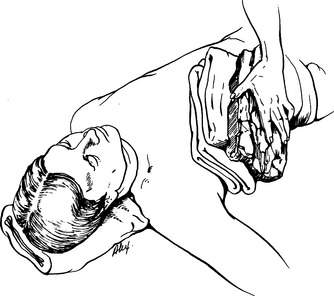

4. Anyone who has a significant flail chest will be unable to coordinate the muscular act of breathing and will need early assistance. The flail segment should be cushioned firmly with pillows, sandbags, or their equivalent (Figure 29). This prevents movement (pain) and eases the act of breathing. If the victim is lying down, turn him onto the side with the flail segment. This stabilizes the injury and allows the good (upside) lung to more fully expand. Use padding underneath the victim to control pain.

5. Broken ribs are best managed with cushioning in a position of comfort and frequent reevaluation of the ability to breathe. Do not tape or tightly wrap the ribs, because this might prevent complete reexpansion of the chest (lung) with inspiration and therefore predispose the victim to shallow, inadequate breathing and subsequent pneumonia. Encourage the victim to take at least one deep breath or give one good cough each hour.

6. Evacuate the victim as soon as possible. If the chest is injured on one side, transport the victim on his side with the injured side down. This facilitates better expansion of the good (upside) lung and more complete oxygenation of the blood.