Chapter 25. Chest injuries

Deaths following injuries to the thorax usually result from a lack of oxygen (hypoxia) or lack of circulating blood volume (hypovolaemia). Injuries may be blunt or penetrating. In blunt trauma the force can be spread over a wide area. After low-energy impacts, damage is usually localised to the superficial structures. In contrast, following high-energy impacts considerable tissue disruption can be produced with severe injuries that may be difficult to manage. The significance of the local damage following penetrating trauma is dependent on both the site and the depth of penetration. In gunshot wounds the degree of injury is also determined by the amount of energy transferred to surrounding tissues.

Blast injuries cause particular injury to the lungs. The shockwave transmits through the tissues and causes injury to the alveoli within the lung tissues. This syndrome is known as blast lung and may lead to hypoxia. High blast pressures can also lead to air emboli which may precipitate sudden death if they obstruct the coronary or cerebral arteries.

Primary survey and resuscitation

The aim of the primary survey is to detect and correct any immediately life-threatening condition. In chest trauma there are six immediately life threatening conditions which can be treated.

These may be remembered using the mnemonic ATOMIC:

A – Airway obstruction

T – Tension pneumothorax

O – Open chest wound

M – Massive haemothorax

i – Fla il chest

C – Cardiac tamponade.

All trauma patients require high flow oxygen

Examination

To be confident that these conditions have been found or excluded, it is important that the chest and neck are examined.

Ideally, all the clothing covering the thorax should be removed so that a full inspection can be carried out.

The neck should be examined for the following:

• Swelling

• Surgical emphysema with crepitus

• Tracheal deviation

• Neck vein distension

• Bruising

• Lacerations.

Lacerations should only be inspected and never probed with metal instruments or fingers because catastrophic haemorrhage can be precipitated.

The chest can then be examined. This involves the following stages:

• Inspection of the chest

• Palpation of the trachea and ribs

• Auscultation of both axillae, top and bottom

• Percussion of both axillae, top and bottom

• Examination of the back: inspection, palpation, auscultation and percussion.

Inspection

The respiratory rate, depth and effort of respiration should be checked at frequent intervals. Rapid, shallow breathing and intercostal or supraclavicular indrawing are all sensitive indicators of underlying lung pathology. Both sides of the chest should be inspected and compared for symmetry of movement, bruising, abrasions and penetrating wounds. Paradoxical movement (movement of part of the chest wall in the opposite direction to the rest, inwards on inspiration and outwards on expiration) may be seen and is a sign of a flail segment.

Palpation

Starting at the top, the clavicles should be carefully palpated for deformity (which may be visible) and the chest wall should be gently felt for tenderness. Instability or crepitus may be noted. Feel down the sides of the chest and look on your gloves for any blood.

Auscultation

A stethoscope should be used to listen in both axillae in the upper and lower half of the chest to determine if the air entry is equal. Listening over the anterior chest detects air movement in the large airways which can drown out sounds of pulmonary ventilation, particularly if any secretions are present.

Percussion

If there is a difference in auscultation, the findings on percussion of both sides of the chest should be compared. The most likely findings are either hyperresonance (pneumothorax) or dullness (fluid or contusion) on one side compared with the other.

Check the back

It is important to assess the back quickly to determine if there is any evidence of a penetrating injury. If there is time, the examination should include palpation, auscultation and percussion of the posterior aspect of the chest.

Life-threatening conditions

Airway obstruction (ATOMIC)

Obstruction of a major airway can occur within the thorax. In many cases, there is little that can be done about this although cardiopulmonary resuscitation or the Heimlich manoeuvre may dislodge the obstruction.

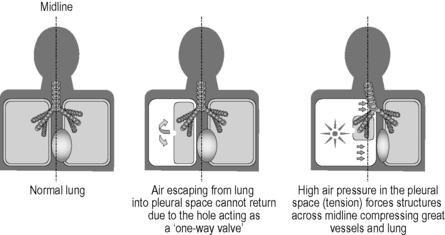

Tension pneumothorax (ATOMIC)

• If there is a breach in either the lung or chest wall, then air can be sucked into the vacuum of the pleural space and a pneumothorax created

• It is important to remember that the pleural cavity and apex of the lung project above the clavicle. Consequently this can occur following penetrating injuries to the lower neck

• Following trauma, a one-way flap valve may be produced on the lung surface. This allows air to be sucked into the pleural cavity during inspiration, but obstructs its escape during expiration

• With subsequent breaths, the volume and pressure of air in the pleural cavity increase. This causes the underlying lung to collapse and profound hypoxia to develop

• In the later stages, the mediastinum is displaced towards the opposite hemithorax, impeding venous return and diminishing cardiac output. This is a tension pneumothorax and is fatal if not rapidly relieved

• It is important to remember that this condition can develop rapidly at any stage of the resuscitation. Consequently a high index of suspicion is always required

• Positive pressure ventilation may convert a simple pneumothorax into a tension pneumothorax

• If the patient deteriorates after artificial ventilation and ventilation becomes progressively more difficult, think: tension pneumothorax.

|

| Figure 25.1. |

| Development of a tension pneumothorax. |

Signs of a tension pneumothorax

• Rapid respiratory rate

• Decreased air entry to the hemithorax

• Hyper-resonant hemithorax

• Rapid, weak pulse

• Decreasing level of consciousness

• Deviated trachea – away from the affected side

• Raised jugular venous pulse (if no accompanying hypovolaemia)

• Cyanosis (very late).

Management

• As an emergency measure, a 14-gauge cannula connected to a 10 ml syringe should be inserted into the second intercostal space in the midclavicular line on the affected side aspirating continuously

• The aim is to decompress the chest by equalising the pressures on either side of the chest wall. A rapid release of air confirms the diagnosis, following which the cannula is slid over the needle into the pleural cavity and the syringe and needle removed

• The cannula usually lasts no more than about 15 minutes before becoming kinked thus requiring a repeat needle decompression

• Insertion of a chest drain will be required when the patient reaches hospital.

Open chest wound (ATOMIC)

• An open chest wound will automatically produce an open pneumothorax on the same side

• If the wound is greater than two-thirds the diameter of the trachea then air preferentially enters the chest through this hole during inspiration (‘sucking’ chest wound)

• This causes failure of ventilation of the lung which eventually collapses

• If the wound or an inadequate dressing acts as a one-way valve then a tension pneumothorax will develop

• The immediate management of an open chest wound is to apply an Asherman® or Bolin® chest seal. Air can then escape during expiration, but cannot enter through the wound during inspiration because the valve is sucked closed

• The primary survey can then be completed and the patient transferred to hospital where a chest drain is inserted via a freshly created incision

• If an Asherman® or Bolin® seal is not available, a dressing sealed on three sides only can be used.

Massive haemothorax (ATOMIC)

• A massive haemothorax is defined as the presence of more than 1.5 litres of blood in the chest cavity; it usually results from laceration of either an intercostal vessel or the internal mammary artery

• Intravascular access must be achieved and fluid resuscitation following standard protocols should be followed

• The remainder of the primary survey should be completed and the patient rapidly transferred to hospital.

Signs of a massive haemothorax

• Decreased air entry on the affected side

• Dull percussion note over the affected side

• Shock, grade II, III or IV

• Jugular venous pressure usually low.

Flail chest (ATOMIC)

• Flail chest occurs when two or more ribs are fractured in two or more places or when the clavicle and first rib are fractured

• Normally the chest moves out during inspiration and in with expiration. When a rib is fractured in two places the middle section can move independently from the relatively fixed ends and tends to be drawn in during inspiration and pushed out in expiration. This is known as paradoxical movement

• Shortly after trauma, this type of movement will only be evident if there is either a large flail chest (over five ribs) or a central flail (multiple bilateral costochondral fractures with a flail sternum)

• More commonly, the spasm of the chest wall musculature is sufficient to splint the flail segment and mask paradoxical movement for a short time

• A flail segment can be a life-threatening condition, mainly because of the underlying pulmonary contusion which adds greatly to the hypoxia already produced as a result of the impaired breathing

• Manual stabilization of the flail segment may be considered.

Management

• Hypoxia must be corrected. Give high-flow, warm, humidified oxygen

• The patient may benefit from lying on the injured side

• Strapping the flail segment with adhesive tape may improve ventilation

• The definitive management is positive pressure ventilation so the patient should be transferred urgently to the Emergency Department

• The patient must be carefully monitored for signs indicating either the development of a tension pneumothorax or that immediate intubation and ventilation are required to prevent further deterioration

• The warning signs include:

• Exhaustion

• Respiratory rate greater than 30/minute

• Significant associated injuries of the abdomen and head

• Pulse oximeter reading of 85% or less on air

• Pulse oximeter reading of 90% or less with supplemental oxygen.

Cardiac tamponade (ATOMIC)

• A small collection of blood within the pericardium will constrict the heart, compromising ventricular filling and hence cardiac output

• This condition is known as cardiac tamponade and usually follows penetrating chest wound within the anatomical area indicated in Figure 22.1

• Cardiac tamponade may be temporarily relieved by pericardiocentesis. Aspiration of even a few millilitres of blood may be life-saving

• In all cases an urgent thoracotomy is necessary if the patient is to survive: rapid transfer to hospital is essential

• Cardiac arrest warrants immediate (‘ crash’) thoracotomy to expose the heart and decompress the pericardium if sufficient medical expertise is available.

Secondary survey

The secondary survey involves a detailed head-to-toe examination but is seldom performed in the prehospital environment. There are eight potentially life-threatening conditions which may be identified during a more detailed assessment of the patient:

1. Pulmonary contusion

2. Cardiac contusion

3. Ruptured diaphragm

4. Dissecting aorta

5. Oesophageal rupture

6. Simple pneumothorax

7. Haemothorax

8. Ruptured bronchi.

Most of these conditions are only ever identified on CT scan.

Monitoring the patient

The patient will require a baseline set of observations including pulse rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, capillary refill time, temperature and if time permits a blood glucose measurement. He/she should be transferred on full monitoring including ECG leads, blood pressure and oxygen saturation probe and should not be left unattended.

Analgesia in chest injuries

Nitrous oxide and oxygen inhalation (Entonox) is contraindicated in chest injuries not only because it will reduce the inspired oxygen to 50% but also, and most importantly, because nitrous oxide will diffuse rapidly into a simple or potential pneumothorax to produce a life-threatening tension pneumothorax. The analgesia of choice is therefore intravenous opiates titrated to effect.

For further information, see Ch. 25 in Emergency Care: A Textbook for Paramedics.