CHAPTER 21 Chemical Peeling: Independent or in Conjunction with Facial Plastic Surgery

The most skilled seamstress can change the dimensions and draping of a piece of cloth but cannot turn a cotton shirt into a silk blouse. Similarly, a surgeon can lift, resect or reposition skin but cannot change the quality, texture, or elasticity of the skin with surgery alone. This reality is a major limitation of surgery.

Fortunately, skin rejuvenation procedures do improve the quality, texture, and elasticity of the skin.1 There are many methods and techniques to rejuvenate the skin including topical cosmeceuticals, dermabrasion, chemical peeling and laser resurfacing. All of these methods are effective in rejuvenating the skin. The most superficial layer, the stratum corneum may be removed with exfoliants, mild alpha hydroxy acids or abrasives. This will give the skin a healthy glow by removing the outer, thickened dead keratin layer and may soften very fine rhytids. Removal of deeper skin layers can be accomplished with dermabrasion, chemical peeling or laser resurfacing. Dermabrasion and chemical peeling are operator dependent for precise control of wound depth. Thus, there is an artistic component to achieving consistent results from these methods. Laser resurfacing, on the other hand, is more precise in regards to wound depth. It is less operator-dependent and theoretically more safe than the other methods. It is extremely important to be well versed in all techniques of skin rejuvenation as well as the basics of wound healing. The authors perform all of the above techniques, individualizing the techniques to the patient’s needs and desires (Fig. 21-1). This chapter will concentrate on chemoexfoliation as the time tested mainstay and still popular method of skin rejuvenation.

Introduction

Chemical peeling or chemoexfoliation, is the process in which the skin is wounded or burned with a chemical agent. The zone of cellular destruction and depth of the wound is dependent on several variables including the peeling agent, the concentration of the agent, skin thickness and skin permeability.1 The immediate reaction of the skin is a second-degree, chemically induced burn. Inflammation begins shortly after the peel and extends variably into the epidermis and dermis. The inflam-matory response peaks at 48 hours but skin rejuvenation and collagen remodeling may last for weeks or months. Regeneration of the surface epithelium begins almost immediately and is usually complete by 5–14 days.

No matter which technique is utilized, if the wounding depth is significant there will be some permanent changes to the skin. The papillary dermal collagen changes from a wavy pattern to straight and parallel beneath the epidermal layer. The dermis shows fibroblastic proliferation and replacement of much of the old deformed elastic fibers with new elastic fibers.2 Depending upon the degree of wounding and chemicals used, there may be fewer melanocytes both in the basal layer as well as in the dermis. This accounts for the lightening in color after peeling. This lightening, again, is a spectral change and may be permanent depending again upon the degree and agent of wounding. With fewer melanocytes the ability to tan is diminished accordingly. In terms of texture, the skin itself becomes smoother and more light reflective (shinier) which is generally a healthy replacement for the previously sun-damaged skin (Fig. 21-1). The potential increased sun sensitivity due to decreased melanocytes makes sun protective measures very important.

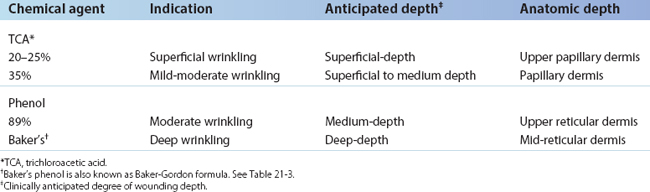

In general, the deeper the wound, the deeper the zone of replacement of old, damaged, and disorganized skin structural elements with new, healthy, and well-organized elements.3 By the same token, the deeper the wound, the greater the potential for scarring and pigment changes. Chemical peels may be divided into three types, graded by the depth of the wound (Table 21-1). Superficial-depth wounding is to the stratum granulosum, papillary dermis. Medium-depth wounding is to the upper reticular dermis. Deep-depth wounding is to the mid-reticular dermis.

Indications and patient selection

Chemical peeling is often performed in conjunction with blepharoplasty, endoscopic brow lifting and facelifting. In general, skin that has been surgically undermined is not peeled at the same time as surgery. If the depth of surgical dissection is subcutaneous, it is possible that superficial damage to the skin from the chemical peel may result in full thickness skin necrosis. However, if the depth of dissection preserves the subdermal vasculature, as in subperiosteal facelifting or transconjunctival blepharoplasty procedures, simultaneous peeling is considered safe.

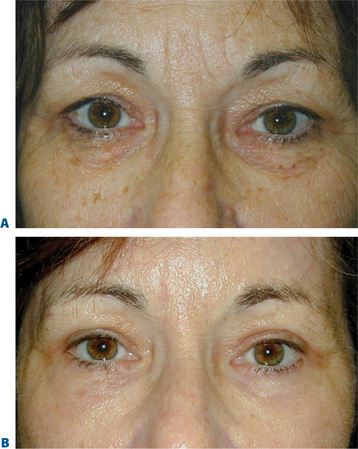

Simultaneous transconjunctival blepharoplasty and chemical peeling has been performed since 1989.4 The primary aim of lower blepharoplasty is either the removal or repositioning of fat in order to address the undesirable convexity (bulging) of the lower eyelid and/or central midface concavity. Approximately 70 percent of patients who want to undergo lower blepharoplasty have such a small component of excess skin that the risk of the transcutaneous approach outweighs the advantage of removing a few millimeters of vertical skin, particularly when the skin problem is mostly due to actinic damage. The authors have been performing only transconjunctival blepharoplasty approaches on these patients for the past 20 years.

One of the authors (DMM) developed and has refined the technique of simultaneous transconjunctival blepharoplasty and chemical skin peeling since 1989.4 We now all routinely use this combination procedure (Fig. 21-2). The 70 percent of patients in whom skin removal has too great a potential risk will all potentially benefit from simultaneous transconjunctival blepharoplasty and chemical peel rejuvenation of the skin of the lower eyelids; in fact, many of the 30 percent in whom the risk of blepharoplasty is acceptable can also significantly benefit from this simultaneous blepharoplasty and chemical peel without the risk of an infralash incision.

Chemical peeling is also performed in conjunction with facelifting procedures. In general, lower facelifting procedures will improve the jowls and tighten the neck. It does little to improve the perioral rhytids, general loss of skin elasticity and dyschromia. Upper facelifting procedures (forehead lifts) will elevate the brows and reduce dynamic wrinkles. It will, however, not delete the permanent creases that are often found in the glabella and forehead regions. Depending on the degree and depth of these wrinkles, a variety of chemical peels can safely be performed simultaneously in areas that have not been surgically undermined. Thus, it is common for us to simultaneously perform an upper and lower facelift, transconjunctival blepharoplasty along with perioral, forehead and lower eyelid chemical peeling.

Evaluating the skin5

Hypopigmentation after chemical peel is a concern. Certainly, the issue of skin color change must be thoroughly discussed with the patient preoperatively. The deeper the wounding the more potential for hypopigmentation. In addition, as a chemical, phenol is melanotoxic. Originally it was thought that permanent hypopigmentation presented little or no problem for light-skinned patients (Fitzpatrick’s classifications I–II6) (Table 21-2). We have come to realize that these very light skinned patients will have significant whitening of their skin, especially after deep peels. If a full-faced peel is performed and the edges of the peeling are feathered onto the neck, the hypopigmentation can be easily camouflaged. If, however, individual regions are only peeled, the color contrast between the peeled and non-peeled zones can be quite noticeable. This will force the patient to require a base or foundation make-up to blend the peeled and non-peeled regions.

| Classification (Fitzpatrick)6 | Pigment type | Reaction to sun |

|---|---|---|

| I | Minimum pigment | Always burns, never tans |

| II | Blue eyes, red hair | Usually burns, rarely tans |

| III | Average pigment | Sometimes burns, average tans |

| IV | More pigment | Rarely burns, usually tans |

| V | Much pigment | Minimum burns, mostly tans |

| VI | Most pigment | Never burns, always tans |

Chemexfoliation and wounding agents

Chemical peeling is a commonly performed procedure. The depth (and, therefore, effectiveness) varies with the chemical agent used, its concentration, and the conditions under which it is applied. The wide spectrum of agents and formulas for peeling includes retinoic acid (Retin-A), solid carbon dioxide, sulfur solutions, resorcinol, salicylic acid, alpha-hydroxy acids, trichloroacetic acid (TCA), and phenol and phenol formulas. Table 21-1 lists the most common peeling agents, concentrations, and formulations and the depth to which they can wound.

The surgeon must determine the depth to which he or she wishes to wound the skin, since it is wound depth that determines the potential for the final result. Unfortunately, depth is not simplistically determined by chemical formulas and concentrations, as implied in Table 21-1. Other major factors that help determine wound depth are skin type (Fitzpatrick’s skin classifications I–VI), skin condition and thickness, pretreatment with retinoic acid (Retin-A), alpha-hydroxy acids, alpha-keto acids, low dose cis-retinoic acid, epidermabrasive exfoliants, and defatting preparations. These agents alter the permeability of the skin to the wounding agent. Furthermore, the larger the amount of agent applied, the longer and harder the agent is rubbed onto the skin, and the longer the duration of contact between agent and skin, the deeper the wounding caused by the same agent. Finally, applying tape over the agent (occlusion) drives the chemical deeper into the skin.

Each of the several chemical wounding agents (see Table 21-1) may be used in various strengths. The most common agents, in increasing order of strength, are TCA (15, 20, 25, 35%) and phenol 89 percent. Most wounding agents can be driven deeper into the skin, and thus cause a deeper burn, by occlusion (taping or ointments), wetter applications, multiple applications, or vigorous scrubbing of the agent into the skin. Due to the increased risk of scarring due to uneven penetration, the authors do not use taping as a method of penetration enhancement. Thus, we will not discuss taping in this chapter.

It is thought, though still not conclusively proven, that phenol’s ability to wound increases with the dilution. (That is to say, the more dilute the phenol preparation, the greater the penetration.) Phenol preparations such as Baker-Gordon formula (Table 21-3) dilute the phenol and use additional ingredients. Studies have shown that the most toxic phenol preparation is a phenol and water combination of 2 : 1. Thus, any dilution of full-strength phenol preparation, as occurs when tears run onto the eyelid, may increase the depth of penetration.

| 3 ml 89% liquid phenol (USP) |

| 2 ml tap water |

| 8 drops liquid soap (Septisol) |

| 3 drops croton oil |

The chemical solutions themselves must be reliably mixed and fresh. TCA solutions are mixed from crystals every 180 days and stored in amber colored bottles. The mixed solution may be purchased from a pharmacy. A 35 percent TCA concentration is obtained by mixing 35 g of TCA (USP) crystals with 100 ml of distilled water. The solution should be stirred before use in case some of the crystals may have come out of solution. Evaporation increases the concentration of TCA, therefore, bottles must be securely closed. Baker-Gordon formulas are mixed fresh daily. Full-strength phenol (89 percent) remains stable on a long-term basis in the manufacturer’s amber glass bottle. Acetone may be purchased from the pharmacy and is used straight out of the bottle on a gauze pad (2 × 2 or 4 × 4 in) to cleanse the skin.

Pretreatment with retinoic acid (retin-A) and bleaching agents

Topical retinoic acid (Retin-A) is the acid form of vitamin A. Studies of daily use of retinoic acid for 6 months have demonstrated it to be an effective treatment for wrinkling, actinic and pigmentary changes.7 Pretreatment with retinoic acid for 2 weeks before chemical peeling usually results in a more even uptake and penetration of the chemicals, and a quicker re-epithelialization. In addition, this pretreatment may allow for deeper wounding with a given chemical concentration and application technique. Retinoic acid is available in varying concentrations. The most potent and irritating forms, in descending order, are: 0.025 and 0.01 percent gel, and 0.1, 0.05, and 0.025 percent cream. We usually have the patients use the 0.1 percent cream, applied nightly to the affected regions. Retinoic acid commonly causes a retinoid dermatitis, which is a pharmacologic irritation and not an allergy. The potency and frequency of application should be adjusted to minimize excessive irritation, but the patient must recognize that some degree of irritation must be manifest to attain benefit.8 Beginning again 2 weeks after peeling (after resolution of significant inflammation), regular use of retinoic acid may be continued indefinitely. The use of retinoic acid (just like the chemical peel itself) causes an acceleration in healing and a reduction of blotches, pigmentary changes, and fine wrinkling, with a smoothing of the surface and an improvement in color from the sallow complexion of actinically damaged and intrinsically aged skin to a healthy, rosy glow. All of these results should enhance all types of cosmetic surgery of the face.

Chemical peeling technique

Application of 35 percent TCA

On the upper eyelid, we prefer to apply the chemical while the patient’s eyelids are closed. We recommend beginning with the crow’s feet superior to the lateral canthal angle and proceeding across the upper eyelid laterally to medially along the inferior border of the eyebrow, then inferiorly down to the eyelash margin, the inner canthus, and the radix of the nose. This is in contrast to the method of McCollough and Hillman,8 who peel no closer than 2–3 mm from the eyelash margin. The chemical is carried into the eyebrow. There is no damage to the eyebrow cilia from chemical peeling in the eyebrow. (By the same token, the chemical peeling on the forehead is carried into the scalp in a full-face peel.)

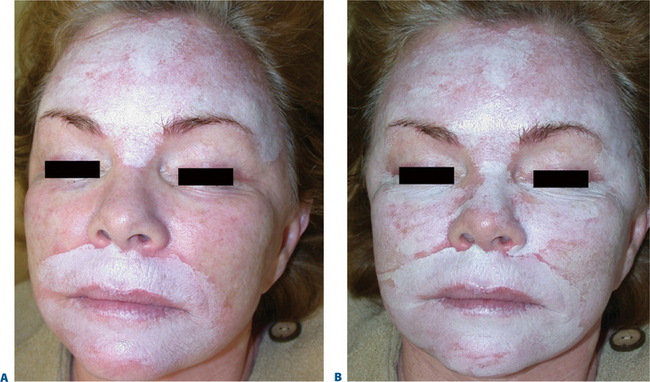

Once applied, the chemical will produce a white blanching or frosting of the skin. This frosting becomes more prominent over 5–10 minutes, signifying a deeper chemical burn. The extent and speed of frosting are determined by the concentration and amount of TCA applied and by how briskly the applicators are rubbed into the skin (Fig. 21-3). In another 5–10 minutes, the frosting begins to fade, and a deep erythema manifests itself. The surgeon must look through the frosting to see the erythema. With experience, the surgeon can judge the depth of wounding by the relative timing of onset and density of the frosting and the erythema. Generally, the ‘whitening’ of the skin signifies epidermal protein coagulation and is the end point of the application. Deep frosting may last 20–30 minutes before beginning to fade.

Modifications

Deeper penetration of TCA 35 percent can also be achieved by first peeling the skin with Jessner’s solution (Table 21-4). The Jessner’s solution destroys the epidermal barrier allowing a more even application and deeper penetration of the TCA 35 percent peel. This peel combination was first described by Gary Monheit,9 and is currently the workhorse of peeling in one of our practices (JH). The procedure is similar to that described above. The skin is cleaned with acetone and the Jessner’s solution is applied with cotton-tipped applicators. The frosting achieved from the Jessner’s solution is quite light and splotchy. It is usually not painful and the patient feels a slight increase in heat. After the Jessner’s solution dries (typically 4–5 minutes) the TCA is applied as described above.

| Resorcinol | 14 g |

| Salicylic acid | 14 g |

| Lactic acid | 14 ml |

| Ethanol (qs) | 100 ml |

Management after chemical peel

Management is similar after all chemical peeling procedures, varying only with regard to the total area peeled and the depth of wounding in that area. A partial thickness of the peeled skin dies on the first postoperative day. This dark or ashen gray skin begins to spontaneously peel off usually on the third day (Fig. 21-4). Beginning on the first day after chemical peel, the patient should institute a regimen of facial cleansing twice a day, followed by application of a thin film of ointment.

Repeated chemical peels

Chemical peeling may be repeated one or more times to achieve the desired result. Whereas some authors encourage deep-depth wounding on the first peel, theorizing that the first peel has the least risk of scarring and complications, other authors advise the use of repeated medium-depth peels, to lessen the shock of pigment changes and reduce the risk of complications. We discuss the options with the patient and decide on the depth of peeling and considerations for subsequent peeling on the basis of all factors, including how soon afterwards the patient must resume appearing in public. We frequently perform a simultaneous upper blepharoplasty, lower transconjunctival blepharoplasty, and chemical peel with 35 percent TCA. This may be followed as early as 14 days later or at any subsequent time by a repeat peel using TCA 35 percent or 89 percent phenol if so deemed appropriate. If further improvement is desired, a third peeling procedure may be performed after completion of healing of the second peel usually at 4 days or longer.

Complications

Splotchy hyperpigmentation

If splotchy hyperpigmentation occurs, it usually can be successfully treated with a combination of 0.05 percent retinoic acid cream (Retin-A) at bedtime and 4 percent hydroquinone cream in the morning for a few weeks. If this regimen is not successful, the skin may be re-peeled to remove the splotchy hyperpigmentation. Strict avoidance of sunlight on the re-peeled skin should prevent recurrence.

Cicatricial ectropion, lid retraction, and lagophthalmos

One of the benefits of chemical eyelid peeling is a vertical shortening of the skin. If more vertical shortening than is desirable occurs, it will manifest as lagophthalmos with corneal exposure, lower eyelid retraction, or early lower eyelid margin ectropion or frank ectropion.10 Exposure symptoms are far more common in patients with an underlying case of dry eyes. Following a dry eye work-up, management with artificial tear supplementation and bland ointment at night, consideration for punctal occlusion or bandage contact lenses is appropriate. The lower eyelid is managed with weekly or bimonthly injections of a total of 0.2 to 0.3 ml of triamcinolone (10 mg/ml) combined with 5-flurouracil (50 mg/ml) injected into the skin in a horizontal line just inferior to the lower eyelash margin. Further help can be achieved by support of the lower eyelid with sterile gauze strips (Steri-strips) or tape, as is standard for management of post-blepharoplasty eyelid retraction or ectropion. These methods, combined with time, can be expected to resolve the majority of such problems related to chemical peeling.

Authors’ collective experience with complications

Two of us (NS and JH) have performed lateral canthal resuspension with a SOOF and cheek lift11–15 with satisfactory final results in seven patients referred with lower eyelid retraction after chemical peel. The use of a hard palate graft, which is successful for lower eyelid retraction following transcutaneous blepharoplasty, is usually not necessary after chemical peel, because the mid-lamella has not been manipulated and therefore is not scarred.

1 Morrow DM. Chemical peeling of the eyelids and periorbital area. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:102-110.

2 Brody HJ. The art of chemical peeling. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:918-921.

3 Stegman SJ, Tromovitch TA. Cosmetic Dermatologic Surgery. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers, 1984;27-46.

4 Morrow DM: Presentation: ‘Simultaneous CO2 Transconjunctival Lower Lid Blepharoplasty and Chemical Skin Peeling,’ Third International Congress of Aesthetic Surgery, Paris, France, May 20, 21, 22, 1989.

5 Hoenig JA, Morrow D. Patient Evaluation. In: Carniol PJ, editor. Laser Skin Rejuvenation. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1997.

6 Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869-871.

7 Kligman AM, Grove GL, Hirose R, Leyden JJ. Topical tretinoin for photoaged skin. Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:836-859.

8 McCollough EG, Hillman RA. Chemical face peel. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1980;13:353-365.

9 Monheit GD. Advances in chemical peeling. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 1994;2:5-9.

10 Wojno T, Tenzel R. Lower eyelid ectropion following chemical face peeling. Ophthalmic Surg. 1984;13:596-597.

11 Shorr N, Fallor MK. Repair of post blepharoplasty ‘round eye’ and lower eyelid retraction, combined cheek lift and lateral canthal resuspension. In: Ward PH, Berman WE, editors. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery of the Head and Neck, Vol 1, Aesthetic Surgery. St Louis: CV Mosby; 1984:279-290.

12 Shorr N, Fallor MK. ‘Madame Butterfly’ procedure: Combined with cheek and lateral canthal suspension procedure for post blepharoplasty ‘round eye’ and lower eyelid retraction. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;1:229-235.

13 Shorr N, Goldberg RA. Lower eyelid reconstruction following blepharoplasty. J Cosmet Surg. 1989;6:77-82.

14 Hoenig JA, Shorr NS. The suborbicularis oculi fat in aesthetic and reconstructive surgery. Inter Ophthal Clin. 1997;37:179-191.

15 Hoenig JA, Shorr NS, Goldberg R. The Verstaile SOOF Lift in oculoplastic surgery. Fac Plast Clin. 1998;6:205-219.