Chapter 44. Chemical incidents

Chemical casualties may be generated from a wide range of incidents including explosions, fires, leaks, spills or through the ingestion of contaminated water. This can result in casualties suffering from a multitude of injuries including:

• Burns (thermal, chemical or both)

• Trauma

• Environmental effects (hypothermia)

• Acute poisoning

• Fire and explosion.

However, the direct effects of exposure to chemicals may result in:

• Acute or chronic poisoning from the absorption of the chemical through the lung, skin or digestive tract

• Direct tissue damage to the skin or lungs.

The severity of these injuries will depend on a number of factors including:

• The strength of the chemical

• The prevailing environmental conditions

• The length of time an individual is exposed to the chemical.

The first priority is to remove the casualty from the main area of chemical exposure (the hot zone) and then second, to decontaminate the casualty as quickly as possible.

Hazard warning symbols

The standard diamond-shaped hazard warning symbols indicate to both the emergency services and the public the primary hazard present. Symbols represent hazards including flammable solids or liquids, flammable or toxic gases, compressed gases, oxidising agents and corrosive substances. On multiloads, the hazard warning diamond simply contains an exclamation mark.

|

| Figure 44.1. |

| Conventional hazard warning signage. |

|

| Figure 44.2. |

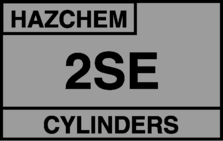

| A HAZCHEM plate. |

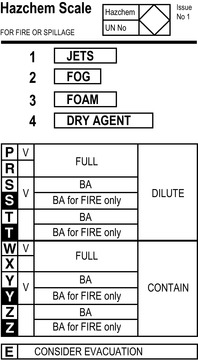

The HAZCHEM action code system

The HAZCHEM code system is a set of code numbers and letters displayed on a vehicle carrying hazardous substances which gives information about the appropriate fire-fighting methods and personal protection needed to deal with a spill.

HAZCHEM also gives guidance as to whether or not the substance can be safely washed into drains and whether evacuation of surrounding areas should be considered.

The HAZCHEM plate displayed on vehicles will also show the diamond warning sign, the United Nations (UN) number for the chemical carried and a contact number for specialist advice from the manufacturer.

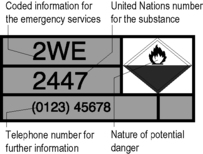

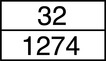

ADR Kemler code

The ADR system is the European road transport system of hazardous load markings. Vehicles must bear a 40 × 30 cm label on both front and rear. The label is in two parts: the upper bears the Kemler code and the lower the UN substance number.

|

| Figure 44.3. |

| HAZCHEM code system aide-memoire card (front). |

|

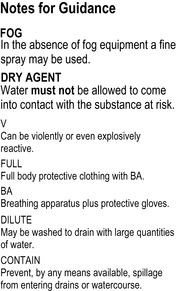

| Figure 44.4. |

| The HAZCHEM code system aide-memoire card (back). |

The Kemler code comprises two or three digits which indicate the properties of the load carried. The first digit describes the primary hazard and the second and third digits the secondary hazards. If the same number is repeated, this indicates an intensified hazard. An ‘X’ in front of the UN substance number indicates that it must not be brought into contact with water. There is no provision in the ADR system for any words to be placed on the warning plate.

|

| Figure 44.5. |

| Kemler plate. |

Transport emergency cards

Transport emergency (TREM) cards exist for road and rail transportation of hazardous loads. For road transport, the TREM card is a standard A4 size; it is kept in the cab of the lorry and should be changed each time the load is changed. This card gives details of the hazard, protective clothing necessary and action to be taken in the case of spillage or fire. The card will also carry first aid information for contaminated casualties and specialist contact details.

The information gathered at the scene from the above hazard warning systems can be supplemented and verified by the use of CHEMDATA. This is a database of many thousands of chemicals and the emergency actions required following exposure provided by the National Chemical Emergency Centre at Harwell.

The role of the Fire service

Most fire brigades now have specialised vehicles and personnel trained in the management of chemical incidents. They will have appropriate gas-tight clothing and breathing apparatus to allow them to work in a toxic and contaminated area. The fire brigade will also provide decontamination facilities for their personnel, usually in the form of portable showers.

The role of the Ambulance service

Ambulance services now have responsibility for the decontamination of chemical casualties. All UK ambulance services therefore must have rapid access to personal protection equipment (PPE) and decontamination equipment suitable for use on contaminated persons who are not wearing personal protective equipment. The Fire service have equipment for the decontamination of large numbers (>50) of uninjured survivors.

Management

The management of hazardous materials (HAZMAT) incidents is generally dealt with under the following headings:

• Prevention

• Preparedness

• Response

• Recovery.

Prevention

The responsibility for prevention of chemical incidents normally lies outside the ambulance service, although senior management will normally have been engaged with the risk assessment process within their own service area.

Preparedness

The paramedic dealing with such incidents must be confident about the use of PPE and undertaking clinical procedures, including decontamination while wearing these systems.

Response

Command and control

The incident area will be divided into a series of zones.

Hot zone

Only those personnel with the right level of PPE and training will be allowed to enter; normally this is the Fire service. Hazardous Area Response Teams (HART) may assist in treating casualties in the hot zone.

Warm zone

The warm zone extends from the hot zone to the inner cordon and is where the triage and decontamination of casualties and decontamination of all emergency service personnel is carried out.

Cold zone

This final zone extends out from the inner cordon to an outer cordon (this will be put in place by the police) and is an area free from contamination. While direct contamination should not be a hazard in this zone, vapour, particularly if the wind direction changes, may cause a problem and therefore respiratory protection (only) may be required by personnel working in this area.

Information gathering

At the scene of any incident involving chemicals, it is important to gather intelligence about the chemicals involved, their quantities, toxicity and the countermeasures that may be necessary. Paramedics should be able to gain enough information to determine whether special chemical precautions are required.

Safety at the scene

In relation to the hazard information, the appropriate level of PPE should be worn. If there is any doubt, it is important to start with the maximum level of protection and work downwards as more information becomes available.

Therefore, rescuer safety consists of ensuring that:

• The appropriate level of PPE is worn (this will be dictated by local policies) and once a task is finished effective personal decontamination takes place

• Casualties are appropriately decontaminated (this stops further injury and prevents contamination of other healthcare personnel)

• If the chemical is unknown a maximum level of PPE is the most appropriate initial response which can be downgraded as more information becomes available.

Triage of chemical casualties

Chemical incidents may produce a large number of casualties with a wide range of problems, but they tend to produce patients in the ratio of:

• Seriously injured (P1) 10%

• Moderately injured (P2) 20%

• Mildly injured/worried well (P3) 70%.

Walking casualties should be moved upwind near the inner cordon emergency service entry/exit gate whereas P1/P2 stretcher casualties should be taken to the casualty decontamination area.

Casualties who are heavily contaminated with chemicals should be triaged for urgent decontamination.

Treatment

Hot zone

Minimal treatment. The Fire service will extract casualties rapidly to the triage area while providing rudimentary airway protection.

Warm zone

Once a casualty has been triaged:

• P3 casualties should be encouraged to self-decontaminate (which is achieved by simply removing their clothes in most cases) before further management in the cold zone

• P1/P2 (stretcher) casualties should be taken to the patient decontamination area and simultaneously the:

• Face should be rapidly decontaminated by washing with water and detergent followed by the appropriate management of the airway using simple airway techniques

• Patient should receive 100% oxygen via a mask with a reservoir

• Rest of the casualty should be decontaminated using the technique described in the section below

• Patient should receive any other basic life support procedure which is necessary, such as the control of external haemorrhage.

Cold zone

The casualty, once decontaminated, should then be handed over the inner cordon onto a patient trolley and any scoop stretchers (or similar devices) should be handed back into the warm zone. Full resuscitation techniques can now be used. The use of antidotes at this level is questionable, the exception being if a specific acute poisoning (or poisonings) is clearly recognised and the antidotes are easily to hand.

Patient decontamination

Avoid taking contaminated casualties to hospital as this may well necessitate the closure of an emergency department to all other casualties. The decontamination team carrying out decontamination must wear appropriate PPE. Avoid hypothermia and protect the patient’s dignity as much as possible.

Equipment required:

• A water source, preferably warm, but with no delay if warm water cannot be found

• A bucket

• Detergent, approximately 10 mL to one 10 L bucket of water

• A soft bristle brush.

Procedure:

1. If the casualty is non-ambulant, he should be placed on either a spinal board or aluminium scoop stretcher

2. Decontaminate the facial area before any ventilation equipment is applied. Once the airway is secured, should this be required, the remainder of the acute care procedures can be carried out

3. Remove all items of clothing unless medically contraindicated. Clothing and valuables should be retained in a sealed plastic bag and the police service consulted regarding their evidential value before disposal

4. Having exposed the patient, rinse the affected areas. This first rinse helps to remove particles and water-based chemicals

5. ‘Vigorously clean’ the affected areas with a soft brush using the detergent solution. This first wipe helps to remove organic chemicals and petrochemicals that adhere to the skin

6. Rinse for a second time. This second rinse removes the detergent and the chemicals. The whole process should not take longer than 5 minutes

7. Repeat steps 5 and 6

8. When decontaminated, the casualty should be passed over the clean/dirty demarcation line onto a clean trolley. Any equipment used during the decontamination process should not pass over the demarcation line.

Evacuation

The casualties in the cold zone should now be a minimal contact hazard. However, chemicals may continue to be ‘off gassed’ from the casualty’s skin or hair or exhaled from the lungs. It would therefore be prudent to ensure that there is effective changeover of air within the back of the ambulance; for some chemicals, respirators may have to be worn.

The emergency department

A decontamination facility and appropriate PPE should also be available at the Emergency Department.

Recovery

If staff are exposed to the chemicals, they should be followed-up in the emergency department and subsequently by the service’s occupational health system. All equipment used in the warm zone will need to be thoroughly decontaminated or destroyed (if decontamination is not an option). Finally, the incident should be internally reviewed and the lessons learned used to change local standard operational procedures and protocols.

For further information, see Ch. 44 in Emergency Care: A Textbook for Paramedics.