5 Checking your performance as a teacher and keeping up-to-date

Teaching is a professional activity that requires:

• mastery of the subject matter that is being taught

• mastery of approaches to teaching that result in students’ effective and efficient learning.

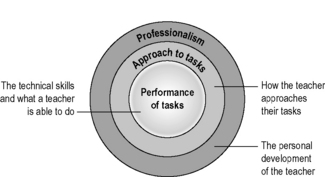

It should be apparent from the earlier chapters that teaching is an immensely complex and multifaceted activity that involves a wide range of competencies and attributes. Teachers, if they are to meet their responsibilities, require a range of technical skills that equip them to impart knowledge, teach practical skills, assess students, conduct small group sessions and facilitate students’ learning in a range of contexts. These technical skills represented by the inner circle in Figure 5.1 are covered more fully in later chapters of the book. The teacher is a professional and not simply a technician. As described in the earlier chapters in this section, teachers have to approach their work with an understanding of the underpinning educational principles, with the necessary passion and appropriate attitudes, and using a combination of evidence-based decision-making and intuition (the middle circle in Figure 5.1).

In this chapter we focus on the personal development and professionalism of a teacher. This is the outer circle in Figure 5.1. Key professional responsibilities include the need for teachers to:

• reflect upon and be aware of their own strengths and weaknesses as a teacher and to be an inquirer into their own competence

• keep up-to-date with new approaches to teaching and learning

• recognise that the teacher is part of a team which involves collaborating with others engaged in the education process.

A general statement of the values and commitments of a teacher that embody the principles of professionalism is given in Appendix 1.

Enquiring into your own competence

• Stop and reflect on your own performance as a teacher. By reading this book you have started this process.

• Study feedback from students about your performance. Students’ views are obtained commonly through a questionnaire or a focused discussion. Feedback should address your coverage of the topic and your method of delivery and presentation skills. The information obtained can be useful, but it has to be treated with an element of caution. In the classic example of what has been termed the ‘Dr Fox Effect’, a professional actor, unbeknown to the students, was briefed to give an entertaining lecture that was educationally poor. It was subsequently rated highly by students!

• Obtain feedback from colleagues. Peer evaluation of teaching is now standard practice in many medical schools. It is important that the feedback provided is constructive rather than destructive. Such feedback is easier to obtain if you are working as part of a team. If you know your peers well, you may be less inhibited to ask for their comments and more likely to receive and accept useful feedback on your performance.

• Record or videotape your teaching. This may be useful, and idiosyncrasies and defects in your teaching may become obvious to you. You can assess your performance on your own or with a colleague.

• Assess whether your students have achieved the expected learning outcomes. One measure is how well your students perform in written or clinical examination questions relating to the part of the training programme for which you are responsible. This information may not be readily available to you.

• Assess whether you have influenced your student’s or trainee’s career choice and subsequent career. This is also a difficult result to measure.

• Study measurements of the educational environment in your institution. Reflect on the possible impact of your teaching on the results.

• Participate in conferences on medical education. Participation in educational activities provides you with the opportunity to compare your teaching practice with that of colleagues. This can help you identify aspects of your own teaching performance which you might wish to improve upon.

Keeping up-to-date

• Textbooks. A growing number of books are available that cover, in more depth than is possible in this book, topics such as curriculum planning, teaching and learning methods, and assessment. A companion volume that discusses some aspects in more detail is A Practical Guide for Medical Teachers.

• Journals. Most teachers keep abreast of the journals relating to their own specialty, but it is unlikely that the discipline-based journals provide adequate coverage of medical education. Key international journals in the field of medical education are Medical Teacher, Medical Education, Teaching and Learning in Medicine and Academic Medicine. You may find more specialised education journals in your own area of teaching such as Education for Primary Care, Anatomical Sciences Education or Medical Science Education.

• Newsletters. Many professional organisations produce newsletters that help to keep their members up-to-date with education developments.

• Guides and reports. The Association for Medical Education in Europe (AMEE) publishes a series of guides designed to keep the practising teacher informed about contemporary medical education practice (www.amee.org). Systematic reviews of evidence relating to topics in medical education are published by the Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) collaboration (www.bemecollaboration.org).

• Online information. Information on a range of education topics can be accessed using a search engine such as Google, by joining a list-serv such as DrEd.com, through an online education community such as MedEdWorld (www.MedEdWorld.org) or by following an education blog.

• Conferences and meetings. Attendance at a local, national or international conference or meeting where the theme is medical education is a popular way of keeping up to date. Some meetings such as the annual meeting of AMEE include in their programme workshops and master class sessions on a range of medical education topics.

• Courses on medical education. An increasing number of courses on medical education are available delivered face to face or at a distance. These may be of short duration or more extended and lead to an award of a certificate, diploma or master’s degree in medical education.

• Membership of professional education associations or communities of practice. One way of keeping up-to-date is to join a professional organisation committed to medical education. This may be a regional educational organisation such as the Association for the Study of Medical Education (ASME) in the UK, the Spanish Society for Medical Education (SEDEM) in Spain, the Netherlands Association for Medical Education (NVMO) in the Netherlands, or the Canadian Association for Medical Education (CAME) in Canada or an international organisation such as AMEE or the International Association of Medical Science Educators (IAMSE). Membership may include a subscription to a medical education journal, registration for conferences, and access to other membership services. It is worthwhile considering joining a network of medical educators such as MedEdWorld.org, which is an online global network of teachers in the healthcare professions who are committed to sharing ideas, resources and expertise in the field of medical education.

Reflect and react

1. Reflect on how you obtain information with regard to your effectiveness as a teacher. Consider the different sources of information listed in this chapter. What are your strengths and weaknesses?

2. Think about how you keep up-to-date in your own discipline or field of interest. Can similar methods be adopted with regard to your responsibilities as a teacher?

3. As a teacher do you work as a member of a team? Do you meet informally with your peers? Are you a member of a curriculum or programme committee? You might consider whether further collaboration with colleagues could be beneficial.

4. Think about your professionalism as a teacher. Could you sign up to the Teacher’s Charter in Appendix 1?

McGaghie W.C. Scholarship, Publication and Career Advancement in Health Professions Education. AMEE Educational Guide No. 43. Dundee: AMEE, 2010.

A description of what scholarship as a teacher in medicine means.

McLean M., Cilliers F., van Wyk J.M. Faculty Development: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. AMEE Educational Guide No. 33. Dundee: AMEE, 2010.