CHASTE TREE

Botanical name: Vitex agnus-castus

Synonyms: Vitex, Chasteberry, Monk’s pepper

CLINICAL INDICATIONS

with amenorrhea and other menstrual irregularities, and cyclic mastalgia. Chaste tree has been shown to increase progesterone levels and lengthen the hyperthermic phase of the basal metabolic temperature curve when taken daily for a minimum of three consecutive months.

IN VITRO, ANIMAL, AND CLINICAL DATA

In vitro and animal studies have demonstrated binding of chaste tree extract and isolated constituents to dopamine (D2) receptors in a dose dependent manner, with a number of studies demonstrating subsequent reductions in prolactin release or levels. In vitro studies have suggested that chaste tree may exert benefits in PMS via a direct endorphin-like effect on opioid receptors as well as indirectly via estrogenic effects, which may lead to an increase in endogenous opioid levels. A weak binding of chaste tree extract components to serotonin receptors has been seen in animal models, hinting at another possible mediating effect of this herb on PMS. Elevations in progesterone levels have been seen with the herb. Ligand binding assays demonstrate competitive binding to estrogen receptors of both the α and β subtypes, although estrogenic effects have not been seen consistently in in vitro assays using methanol extracts of the herb.

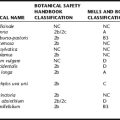

RATINGS

USE IN PREGNANCY AND LACTATION

It has been postulated that increased progesterone levels as a result of improved luteal function associated with the use of chaste tree may partially explain positive results seen by herbal practitioners and midwives when using this herb for the prevention of subsequent miscarriage in women with a history of prior repeated miscarriages. No trials have been conducted to evaluate these claims, and specific data on the use and safety of chaste tree during pregnancy are lacking. Improvements in fertility were discussed earlier in this section. In studies in which pregnancy has been achieved while taking chaste tree, no follow-up studies have been conducted on the pregnancy outcomes or newborn health in those who did not discontinue the herb upon becoming pregnant. Reproductive toxicity studies in female rats at up to 80 times the concentration used clinically in humans showed no difference in offspring compared with controls, and no teratogenicity was seen in the offspring of rabbit dams given up to 74 times the recommended daily dose for humans. A nonsignificant increase in the number of resorptions and placental weight was seen in groups receiving the highest dose, and it is not known whether this was attributable to the alcohol, the herb, or spontaneous events. As stated, the Botanical Safety Handbook gives chaste tree a Class 1: rating, suggesting an ease on prior restrictions during pregnancy.

* This is based on the revised edition, in publication. The prior 2b rating was based on theoretical emmenagogic effect because of the herb’s historical use for menstrual regulation and the treatment of amenorrhea. The 2d rating was reported by Upton in the American Herbal Pharmacopoeia and Therapeutic Monographs: Chaste Tree Fruit to be an unsubstantiated rating, with no reports of inference with oral contraceptives (or any other) in the pharmacologic literature, clinical reviews, or herbal literature.