Chapter 14 CHALLENGING CONSTIPATION

INTRODUCTION

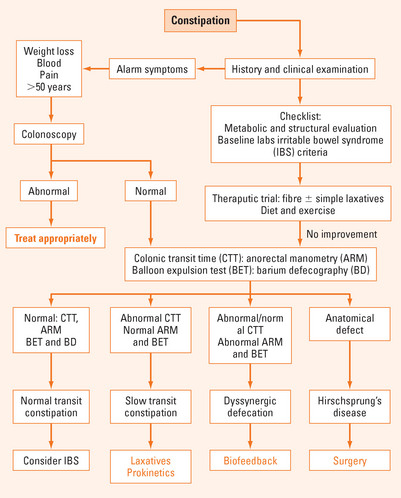

It is important to take a detailed history from a patient presenting with constipation and, in particular, to decide whether it is a new symptom or the first presentation of a long-term complaint. Investigations and treatment will be determined by these factors.

CONSTIPATION IN ADULTS

It is important to differentiate between two important disorders of colonic motility:

ASSESSMENT

History

Simple suggestions on dietary modification can make quite a deal of difference.

Ask the patient to keep a diet diary for a few days. Most people overestimate the amount of fibre and underestimate the amount of fat they consume.

Medications

It is often possible to substitute another medication for a possible culprit and assess the effect.

Physical examination

Some patients, particularly women, are troubled by rectal prolapse associated with long-term straining at stool. This is a symptom that is often not volunteered and direct enquiry and physical examination are required. Many women who have a degree of rectal prolapse will continue to strain at defecation because the sensation caused by the prolapse leads to the belief that there are still faeces in the rectum. A discussion of the mechanics of defecation with the aid of a diagram can be very helpful. Mucosal resection is indicated in some cases. Behaviour therapy, incorporating biofeedback, has a role in some long-term cases.

Investigations

Further investigations

Balloon expulsion test

Provides an assessment of the patient’s ability to expel a water filled balloon. Most patients can expel the device within one minute. If the patient is unable to expel the balloon within 3 minutes, the clinician should suspect dyssynergic defecation.

Anorectal manometry

Can confirm pelvic floor dysfunction, typically with absence or insufficient relaxation of the external sphincter pressure on straining, or poor propulsion, or both. Obstructed defecation may be associated with excessive straining, trouble letting go and a feeling of incomplete emptying. Patients may sit in a very peculiar position to try and empty the rectum. Some patients report splinting the perineum or even performing manual evacuations on themselves.

TREATMENT

It is rare for there to be a ‘quick fix’ in the treatment of chronic constipation. Many people benefit from a bowel program consisting of an improved diet, increased fluid intake and daily exercise. Others may require fibre supplementation or medications (Table 14.1). It is important to emphasise to some patients that they must take responsibility for their improvement by making time to go to the toilet in the morning or answering the call to stool when it comes without straining excessively.

| Type of drug | Example |

|---|---|

| Bulking or hydrophilic laxatives | Psyllium (ispaghula), methylcellulose, bran, plantain derivatives, Aloe vera |

| Surfactant or softening or wetting agents | Docusate, poloxalkol |

| Osmotic laxatives | Sorbital, lactulose, milk of magnesia (magnesium hydroxide), polyethylene glycol (PEG) solutions |

| Peristaltic stimulants | Senna, bisacodyl, cascara |

| Prokinetics | Tegaserod |

| Chloride channel activator | Lubiprostone |

Laxatives

It is useful to give the patient an information sheet about constipation to take home, stressing that it is normal to empty the bowel between three times a day and three times a week, and making clear suggestions about what forms of therapy can be tried for that specific individual and how long they should persevere before asking for further clarification or help. A ‘step-up’ approach works well for many patients. For instance, a simple fibre supplement such as psyllium should be tried for a couple of weeks. If unsuccessful, the dose can be slowly increased or another fibre supplement such as sterculia should be tried for a couple of weeks. If unsuccessful, an osmotic laxative can be suggested. People who have difficulty with evacuation may benefit from glycerine suppositories or a faecal softener. If the constipation has been a very long-term problem, it is worthwhile asking the patient to come back for further evaluation and advice.

SUMMARY

Constipation is a very common problem with a wide spectrum of symptoms including excessive straining, hard stools, feeling of incomplete evacuation, use of digital manoeuvres, or infrequent defecation. An appropriate history and physical examination is required to be sure that the symptom of constipation is not the manifestation of some more serious underlying condition. Functional constipation consists of two major subtypes: slow transit constipation and pelvic floor dysfunction. Patients with irritable bowel syndrome have pain, and may exhibit features of both types of constipation. The condition can be managed in the vast majority of cases with simple advice on diet and lifestyle. Biofeedback therapy is an important advance for patients with dyssynergia.

American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: guidelines on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1761-1778.

Bharucha A, Wald A, Enck P, et al. Functional anorectal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1510-1518.

Brandt L, Prather CM, Quigley EM, et al. Systematic review on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(Suppl 1):S5-S21.

Wald A. Chronic constipation: advances in management. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;9:4-10.