“I need help on the night shift!”

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

• Differentiate between management and leadership.

• Describe theories of management and leadership.

• List characteristics of an effective manager and an influential leader.

• Discuss the elements of transformational leadership.

• Identify distinguishing generational characteristics of today’s workforce.

• Differentiate between leadership and followership.

• Differentiate the concepts of power and authority.

• Apply problem-solving strategies to clinical management situations.

• Identify the characteristics of effective work groups.

• Discuss the change process.

• Discuss the value of using evidence-based management actions.

As you move closer to meeting your goal of becoming a graduate nurse, give consideration to understanding the role of the nurse as a manager and as a leader. You might be thinking:

I do not want to be a manager; I am just a recent graduate!

OR

I want to take care of patients, not be a paper pusher!

OR

Am I ready to be followed by others?

Nursing, in any role, is a people business. Management is the process of effectively working with people. When you accept your first position as a graduate nurse, it is important to realize that you are becoming a part of a work group where members spend at least a third of their day interacting with each other. Therefore, registered nurses must be prepared to use varying levels of management skills, enhanced by interpersonal, followership, and leadership skills, to be effective in their role as a provider of patient care and as member of the care team.

There are multiple levels of management that a registered nurse can practice. The specific level depends on the experience, competency, and defined role of the individual nurse. For example, as a recent graduate, you will have primary management responsibility for the patients for whom you will be providing care. This will include planning and coordinating the care with other nursing personnel, with health care staff, and with the patient and family members. Provision of this level of management is expected from all registered nurses who practice in the acute-care environment.

Management Versus Leadership

What Is the Difference Between Management and Leadership?

Although the terms management and leadership are frequently interchanged, they do not have the same meaning. A leader selects and assumes the role; a manager is assigned or appointed to the role. Leaders are effective at influencing others; managers, as providers of care, supervise a team of people who are working to help patients achieve their defined outcomes. Managers also have responsibility for organizational goals and the performance of organizational tasks such as budget preparation and scheduling. Although it is desirable for managers to be good leaders, there are leaders who are not managers and, more frequently, managers who are not leaders! So, let us discuss the actual differences in more detail.

The Functions of Management

Management is a problem-oriented process with similarities to the nursing process. Management is needed whenever two or more individuals work together toward a common goal. The manager coordinates the activities of the group to maintain balance and direction. There are generally four functions the manager performs: planning (what is to be done), organizing (how it is to be done), directing (who is to do it), and controlling (when and how it is done). All of these activities occur continuously and simultaneously, with the percentage of time spent on each activity varying with the level of the manager, the characteristics of the group being managed, and the nature of the problem and goal.

According to Rothbauer-Wanish (2009), planning is generally considered a basic management function and one on which managers should spend a significant part of their time. The foundation for all planning begins with the development of goals that reflect the mission and vision of the organization and defining strategies that will be implemented to meet and maintain that mission and vision. The next level of planning is used daily as a part of determining the requirements for accomplishing the work to be done and ensuring that what is needed is available. This planning must be congruent with the strategies for meeting the mission and vision of the organization. Along with this approach, a manager must also be able to plan for contingencies, which, if not addressed, will interfere with accomplishing what needs to be done. When managing a patient-care unit, which needs specific resources 24 hours a day, one can be certain that the unexpected will happen. Being prepared for the unexpected is a key function of a nurse manager.

Staff nurses practice the elements of planning as the plans of care for each patient are developed. For this process, the patient’s current status and goals are assessed to determine what needs to occur during the time one is assigned to provide that care. The interventions needed are selected to advance the patient to the point of meeting his or her defined goals. This process of management of patient care uses the same planning skills as those used by someone who has the responsibility of managing staff.

Organizing occurs as the manager aligns the work to be done with the resources available to do that work (Rothbauer-Wanish, 2009). This requires knowledge of all parts of the work, as well as a clear understanding of the competencies required of those who will be performing the assigned work. The manager must consider not only the licensing regulations but also the facility’s policies when organizing the assignment of work. For example, licensing regulations may allow a licensed practical nurse to administer defined intravenous medications, but the facility policy may not allow that level of employee to perform that procedure. Another example would be that the licensing regulations for registered nurses do not specify that a newly licensed nurse cannot be assigned to work in a critical care unit. However, facility policy may state that registered nurses who wish to work in a critical care unit must gain 1 year of other experience before being assigned to critical care service. Knowing this information prevents the manager from making decisions that may be unacceptable.

The next phase of management is providing direction or supervision. The manager retains accountability for ensuring the work is completed in a timely and competent manner. Additionally, staff members need to complete assigned work according to standards, policies, and procedures with the understanding that the manager will provide sufficient observation and assessment of care being delivered to ensure that the care provided is safe and complete. When patient care falls below minimum standards, the manager has two actions to take. The first is to make certain the care and safety of the patient are addressed by ensuring the proper care is provided, and the second is to address the performance of the staff who did not provide the care as assigned. Managers need to be able to make decisions regarding the level of supervision needed by each staff member. Managers must also be able to motivate staff toward reaching their full competence to perform the assigned work with minimal observation and direction.

Staff nurses who are managing the care of patients need to have a clear understanding of the relevant policies and procedures related to the care provided and must be confident that he or she is competent to provide that care. The staff nurse must be cognizant of the expected outcomes of the care to be provided and how to determine if progress toward those outcomes is occurring. Actions to take when outcomes are not being met must be understood by the staff nurse who is managing the care.

Controlling is the last aspect of the planning function of the nurse manager. Most of the controls in health care facilities exist because health care is a highly regulated system, and much of what must be done is dictated by governments, insurers, evaluating agencies, health policy, and institutional policy. The effective manager needs to be cognizant of the regulations that affect his or her area of practice and must be able to clearly communicate the essence of these regulations to the staff. Staff members need to have a thorough understanding of regulations and implications of noncompliance with these regulations. An example of external controls imposed because of regulations is the elimination of the use of certain dangerous abbreviations when a physician writes a medication order (see Chapter 11 for a list of abbreviations). This regulation is a part of The Joint Commission (TJC) Standards, as well as Standards from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Although the initial focus of this regulation is on the physician, registered nurses may not implement an order that includes these eliminated abbreviations.

Control by the manager may also be demonstrated through data collected when reviewing quality of care to determine the level of compliance with standards and other quality monitors. These data give the manager the ability to validate observations, because these observations can represent the outcomes of care that has been provided. For instance, if the rate of hospital-acquired infections continues to be above the expected level, the manager has the information needed to implement and mandate interventions to reduce the number of infections.

What Are the Characteristics and Theories of Management?

Active interest in management as a separate entity was first noted as part of the industrial revolution. The traditional theory developed at that time was based on the premise that there was a need to have the highest productivity level possible from each worker (Wertheim, n.d.). This theory is the basis for the hierarchy that has dominated much of management theory for almost two centuries. This type of management is also known as the bureaucratic theory of management, defined as “dividing organizations into hierarchies, establishing strong lines of authority and control. He [Weber, the author of this theory] suggested organizations develop comprehensive and detailed standard operating procedures for all routinized tasks” (McNamara, n.d.). The manager who functions under the traditional theory follows rules closely and understands the concept of the division of labor and the chain-of-command structure. Historically, this kind of functioning was thought to be efficient and clear and was considered necessary to attain the most work from each employee. Throughout nursing history, this has been the theory on which the work of nurse managers was based. Since the mid-1990s, movement from this traditional theory has occurred, and more appropriate theories have been put into practice in multiple health care settings across the country.

Following the development of traditional theory of management was behavioral theory (also called human-interaction theory). This evolved as it became more evident that the humanistic side of management needed to be addressed (Hellriegel et al., 1999). Employees seeking recourse from some of the rules of hierarchy looked for assistance outside of their place of work, for instance, in the growing labor unions. Employers recognized the need to consider the human side of productivity so as to maintain a stable, satisfied work force.

This was followed by the introduction of systems theory, which considers inputs, transformation of the material, outputs, and feedback (Hellriegel et al., 1999). Systems theory is implemented when consideration is given to the impact of decisions made by one manager on other managers or on parts of the system as a whole. This is important in health care, because it helped management move from making decisions in the traditional manner, in which departments functioned as though they were independent, to recognizing the interdependence of departments on each other. Recognizing that patients cannot be treated as though they are a number of separate and distinct parts has promoted the understanding and importance of systems theory. Whereas behavioral theory as it relates to management considers the attitudes and needs of the employee, systems theory examines the possible outcomes of all individuals affected by a decision.

The last theory of management to be considered is the contingency theory, which is also referred to as the motivational theory (Hellriegel et al., 1999). This theory focuses on the manager being able to blend the elements of the earlier theories, using those elements to determine what motivates people to make choices and leading to the most effective methods to complete the work that needs to be done. All of these theories are directed toward ways to ensure that employees are as productive and timely as possible when working to meet the organizational goals or targets.

What Is Meant by Management Style?

You will experience a variety of management styles in your nursing practice. These styles follow a continuum from autocratic to laissez-faire (Fig. 10.1).

The autocratic manager uses an authoritarian approach to direct the activities of others. This individual makes most of the decisions alone without input from other staff members. Under this style of management, the emphasis is on the tasks to be done, with less focus on the individual staff members who perform the tasks. The autocratic manager may be most effective in crisis situations when structure and control are critical to success, such as during a cardiac arrest or code situation. In general, however, the autocratic manager will have a difficult time in motivating staff to become part of a satisfactory work environment, because there is minimal recognition of the contributions of staff to the work that needs to be done and minimal focus on the necessary relationships that make up the successful health care team. Many individuals, particularly those from generations after the Baby Boomers, will not stay in a position in which autocracy is the major style of management.

On the other end of the continuum is the laissez-faire manager, who maintains a permissive climate with little direction or control exerted. This manager allows staff members to make and implement decisions independently and relinquishes most of his or her power and responsibility to them. Although this style of management may be effective in highly motivated groups, it may not be effective in a bureaucratic health care setting that requires many different individuals and groups to interact.

In the middle of the continuum is the democratic manager. This manager is people-oriented and emphasizes effective group functioning. The goals of the group are identified, and the manager is perceived as a group member who is also its organizer who keeps the group moving in the defined direction. The environment is open, and communication flows both ways. The democratic manager encourages participation in decision making; he or she recognizes, however, that there are situations in which such participation may not be appropriate, and the manager is willing to assume responsibility for a decision when necessary. The democratic style is the blend of autocracy and laissez-faire with assurances that the extreme ends of the continuum are rarely, if ever, necessary.

One example of a democratic manager following either the behavioral or contingency theory would be a manager who creates a Nurse Practice Committee on his or her unit. This committee would have some defined authority and responsibility to address specific items in the practice environment, such as schedules and practices on the unit. This type of committee supports the idea that staff and management are interdependent in governing the successful practice environment (Tonges et al., 2004).

To be a successful manager in today’s hierarchical organizations, the nurse manager will need to adopt a democratic style of management, one that is flexible enough to adapt to the changing roles of nursing staff. The nurse manager should be willing and able to share power with the same people whom he or she will supervise. The successful manager will also need to acquire an element of laissez-faire style for those components of governance that will be under the auspices of the staff. It will be important for staff nurses to develop a balanced combination of autocracy and laissez-faire as they implement shared governance (stakeholder participation in decision making) that will include quality of care and peer review (Institute of Medicine, 2004).

As is evident, the continuum of management styles ranges from what might be considered total control to complete freedom for subordinates. In choosing a management style, the manager must decide on levels of control and freedom and then determine which trade-offs are acceptable in each situation. Behaviors vary from telling others what to do, to relinquishing to another group within the organization the authority for portions of the work to be done. As a new staff nurse, your initial involvement in management occurs when you manage the care of a group of patients. The next involvement may be as a part of the shared governance model that may be developing in your facility. As you gain experience and knowledge, it is important for you to develop an understanding of which style you should use, depending on what you hope to be able to achieve.

Leadership, in contrast, is a way of behaving; it is the ability to cause others to respond, not because they have to but because they want to. Leadership is needed as much as management for effective group functioning, but each role has its place. The manager determines the agenda, sets time limits, and facilitates group functioning. The leader “models change, establishes trust, sets the pace, creates the vision, [provides] focus, and builds commitment” (Manion, 1996, p.148).

What Are the Characteristics and Theories of Leadership?

The many attempts to define what makes a good leader have resulted in a variety of studies and proposals. Researchers have tried to identify the characteristics or traits necessary to be a good leader. Several of these studies have defined the concept of a born leader, implying that the desired traits are inherited. This is often referred to as the “Great Man” theory, because it was first identified when leadership was generally thought to be a male quality, particularly as it related to military leadership (Van Wagner, 2007). With later research, it became clear that desired leadership traits could be learned through education and experience. It also became clear that the most effective leadership style for one situation was not necessarily the most effective for another and that the effectiveness of the leader is influenced by the situation itself. As leadership theories continue to develop, emphasis is more on what the leader does rather than on the traits the leader possesses.

Several other theories of leadership are worth discussing. The first is contingency leadership, which says that leadership should be flexible enough to address varying situations. Although this may sound complicated, it can be compared with your approach to patient care. As a nurse, you individualize a patient care plan based on the needs of the individual. Then the plan is implemented using available resources. The effective leader, using contingency leadership, brings the same flexible approach to each individual situation where leadership is required.

Situational leadership theory resulted from the study of the contingency theory. Under situational leadership theory, the leader attempts to function more closely in the situation being addressed. Blanchard and Hersey (1964) define the situational leader as one who analyzes the needs of the current situation and then selects the most appropriate leadership style to address that particular situation. The selected style depends on the competencies of each employee who will be helping address the current situation. The authors state that a good situational leader may use different styles of leadership for different employees, all of whom are involved in addressing the same situation. This is not unlike what you, as a team leader, will be doing when assigning work to members of your work team. The assignments will need to be individualized based on the competencies of each member of the team to help ensure the patient-care goals can be met.

Interactional leadership is the next theory to consider. With this theory, the focus is on the development of trust in the relationship (Marquis & Huston, 2003). Interactional leadership includes concepts of behavioral theories, which begin to address the theory that leaders are made and not born, because the needed behaviors can be taught and learned. Individuals who function based on the theory of interactional leadership use democratic concepts of management and view the tasks to be accomplished from the standpoint of a team member.

Leadership theory can also be described as transactional, noting that the transactional leader is one who has a greater focus on vision, defined as the ability to envision some future state and describe it to others so they can begin to share that vision. The transactional leader holds power and control over followers by providing incentives when the followers respond in a positive way to the leader’s vision and the actions needed to reach that vision. The basis for the relationship between leader and follower is that punishment and reward motivate people. Transactional leaders seek equilibrium so the vision can be reached and he or she only intervenes when it appears that goals will not be attained (Sullivan & Decker, 2012).

This leadership theory does not sound like one that many would be encouraged to embrace or follow, as the rewards are ultimately one-sided. However, the transactional approach to leadership still exists in most organizations, generally at the management level as incentives are provided to gain a defined level of productivity. One may believe that this approach is closer to management than leadership, which may explain why it might not be effective at other levels in the organization.

Transformational leadership occurs when the leader has a strong, clear vision that has developed through listening, observing, analyzing, and finally by truly buying into the vision to change dramatically the way things are currently done (Bass, 1990). This theory was introduced as early as the 1970s and is still in its infancy of use by particular industries such as health care. However, this theory of leadership is a “major component of the Magnet model developed by the American Nurses Credentialing Center” (Sherman, 2012, p.62).

According to Sherman (2012), there are four key elements that characterize the transformational leadership style. The first element is idealized influence, meaning that the transformational leader is a “role model for outstanding practices which in turn inspires followers to practice at this same level.” Inspirational motivation, the second element, is demonstrated by the leader being able to “communicate a vision” in a manner that others understand. Intellectual stimulation and individual consideration are the last two elements and address the fact that the leader values staff input and creativity while continuing to coach and mentor staff, recognizing there are both group and individual needs and issues to consider (Sherman, 2012, p.64).

Characteristics of transformational leaders, according to Tichy and Devanna (1986), are that these leaders are courageous change agents who believe people will do what is right when provided direction, information, and support. They are also value-driven visionaries, lifelong learners, and individuals who can successfully handle the complexities of leadership. To accomplish their goals, they effectively change the traditional way of leading, which is often from the office, to leading from the place where the action is occurring.

Transformational leadership will be implemented when it is clear to the strong, visionary leaders that the current situation(s) cannot be “fixed” using the traditional methods that have worked in the past. In the early 1990s, Leland Kaiser, a renowned health care futurist, discussed transformational leadership, identifying the transformational leader as the primary architect of life in the 21st century. Many of the predictions made by Kaiser are now being recognized as part of transformational leadership. An example of this is what has occurred at Virginia Mason Medical Center, as the leadership of that organization took on the task of transforming health care at that facility (Kenney, 2011). The entire leadership team has worked together to ensure that this transformation occurred as envisioned.

If transactional leadership involves the use of leadership power over rewards and punishments, transformational leadership can be characterized as a process whereby leader and followers work together in a way that changes or transforms the organization, the employees/followers, and the leader. It recognizes that real leadership involves transformation and learning on the part of follower and leader. As such, it is more like a partnership, even though there are power imbalances involved.

Whereas transactional leadership involves telling, commanding, or ordering (and using contingent rewards), transformational leadership is based on inspiring, getting followers to buy in voluntarily, and creating common vision. Transformational leadership is what most of us refer to when we talk about great leaders in our lives and in society.

The nurse shortage is a good example of a problem in which the solution will most likely be found by transformational leaders. It is evident that the old ways of fixing the nurse shortage have not been effective. Managers, lawmakers, and organizations have tried increasing wages, paying bonuses, recruiting foreign nurses, mandating staff-to-patient ratios, adding nurse-extenders, and implementing flexible shifts. None of these methods has had any long-lasting effects, because they do not address the conflicts that have occurred as newer generations of nurses have reached the level where they want control of their practice as granted by education and licensure. A transformational leader understands the basis for these conflicts and develops a vision, which will address the needs of the people involved in the conflict.

One might anticipate that the Chief Executive Officer and the Chief Nursing Officer of a hospital would both be transformational leaders. These leaders have a responsibility to see the bigger picture and to be able to describe that vision or picture to others. Porter-O’Grady (2003a) describes this type of leader as one who can “stand on the balcony” (p.175). From this position, the leader can monitor the ebb and flow of the organization and determine in which direction the organization is moving. To be effective, the transformational leader must have a vision that can be put into words for others to understand. Check out the relevant websites and online resources at the end of the chapter for additional information on transformational leadership.

Although most leaders tend to lean toward one of the theories discussed here, fluctuations from one to another can occur, depending on the particular situation. In the health care setting, good leaders carefully balance job-centered and employee-centered behaviors to meet both staff and patient needs effectively (Critical Thinking Box 10.1).

An effective leader works toward established goals and has a sense of purpose and direction. She or he must also be aware of how her or his behavior impacts the workplace. Emotions, moods, and patterns of behavior displayed by the leader will create a lasting impression on the behavior of the team involved. It is critical for the leader to be aware of this impact if she or he is going to be effective in managing and leading a team (Porter-O’Grady, 2003b). Rather than push staff members in many directions, the effective leader uses personal attributes to organize the activities and pull the staff toward a common direction.

The most current theory addressing the changing environment in which we work is the complexity theory of leadership. The complexity theory addresses the “unpredictable, disorderly, nonlinear, and uncontrollable ways that living systems behave” (Burns, 2001, p.474). This theory indicates that we need to look at systems, such as those in health care organizations, as patterns of relationships and the interactions that occur among those in the system.

Complexity theory is complex! However, the basis of the thinking can most easily be understood by comparing traditional ways of analyzing an organization to the ways in which this analysis would be accomplished using the complexity theory. The traditional method used to understand an organization is to “break a system into smaller bits and when we believe we understand the bits we put them all back together again and draw some conclusions about the whole” (IOM, 2004). Complexity theory examines the whole rather than the sum of its parts, because breaking a system apart removes all the impact of the human relationships that affect the whole.

Smyth (2015) asked, “Why do we struggle to achieve our goals in clinical outcomes, safety and financial performance in [health care facilities] when these facilities are chockfull of brilliant, well-intentioned people?” It is because those people bring factors such as varying levels of competence and performance and differing emotional states—all of which can have an unpredictable impact on the outcome. In general, most health care organizations work solely through hierarchies, which does not allow for the openness needed to achieve the best solutions to problems being addressed.

Following complexity theory, one understands that organizations are “organic, living systems” (Anderson et al., 2005) in which people act quickly and use knowledge sharing and patterns of relationships rather than the rules of a hierarchy. When leading according to the principles of complexity, change is understood as successful when accomplished by individuals as they adapt to variations in the environment and not as the linear managers dictate. “However, we are still mired in the hierarchical structures we have lived with for more than fifty years—going up and down the chain of command to make decisions…” (Smyth, 2015).

As we complete the discussion on the theories and characteristics of leaders and managers, it becomes evident that there are more differences between these two groups than those briefly identified in the opening paragraph of this discussion. According to Manion (1998), the major differences are

• Leaders focus on effectiveness, and Managers focus on efficiency.

• Leaders ask what and why, and Managers ask how.

• Leaders initiate innovation, and Managers maintain the status quo.

• Leaders look to the horizon, and Managers look to the bottom line (pp.3–7).

Management Requires “Followership”

Individuals can manage things, processes, and people. When thinking of nurse managers, it is generally assumed they are managing people, who are managing the care of patients. When being managed, one is in the role of a follower—an essential role in the safe and effective delivery of patient care. The role of the follower is not always considered when discussing management functioning, but it is obvious that those who are expected to follow the direction of the manager are essential to the success of the manager.

Followership is “the ability to take direction well, to get in line behind a program, to be a part of a team and to deliver what is expected of you” (McCallum, 2013). There cannot be a truly effective leader without competent followers since if the followers fail in the work they are doing, the manager will not be able to successfully complete the assigned work.

From the above information, it appears there are significant differences between leadership and followership. While this is true, the interconnections between these two functions make the differences almost irrelevant. “You can’t have one without the other!” truly applies. They need each other to exist and to have a purpose.

While many believe followers are subservient to leaders, leaders are beholden to followers for both leaders and followers to be successful. Followers must have the ability to think critically and actively participate in the successful completion of the leadership directions/goals (Miller, 2007).

When assessing the success of a team or group of staff, it is important to remember that, at times, individuals assume either leadership or followership roles or assume both leadership and followership roles during the completion of required tasks. A successful leader understands the role of followers and recognizes that followers should receive credit for the success of the team/group just as the leader receives this credit (Miller, 2007).

The Twenty-First Century: A Different Age for Management and for Leadership

The face of leadership is changing, and this is very evident in nursing and health care. Changes in health care are altering some of the foundations of nursing practice. Shorter hospital stays and emerging therapeutics require less, but perhaps more intense, clinical time and challenge the need for certain nursing interventions that have become routine over time. Nurses are becoming increasingly frustrated with the reality that the nursing care they were taught to provide—and they feel they need to provide—is not possible given the decreased time spent with their patients (Porter-O’Grady, 2003c). This dissatisfaction may be compounded by the conflict between established nurses and upcoming generations of nurses. In general, younger generations of nurses have accepted the newer foundations of practice, whereas these changes are often resisted by tenured staff. Thus the task of learning how to bridge the gaps in a multigenerational staff must be added to the nurse manager’s other responsibilities.

The generations that have retired or will soon retire in the nursing profession include those born during the 1920s, 1930s, and early 1940s, sometimes referred to as the Silent Generation or the Veteran Generation. The generations currently active in the nursing profession include the Baby Boomer Generation, born more or less between 1945 and 1960; Generation X, born between 1960 and 1980; and the Millennial Generation, born between 1980 and 2000 (Carlson, 2014).

The leadership of health care in the 21st century has been and will continue to be significantly affected by the diverse generations in today’s workplace. These generational groups have major differences in communication styles, in what motivates them, in what turns them off, and in their workplace ideals (Boychuk-Duchscher & Cowin, 2004; Martin, 2004). Great diversity also exists in the beliefs, attitudes, and life experiences of these various generations (Scott, 2007). As such, generational diversity has been recognized as one of the major factors precipitating conflict in the workplace. Box 10.1 lists time frames of each generation as well as the percentage of each generation in the workforce.

The Silent or Veteran Generation

This oldest generation of nurses, which is also the group that is retiring or retired, was taught to rely on tried, true, and tested ways of doing things. Because of early experiences with economic hardship and living through the Great Depression of the 1920s and 1930s with their families, these nurses place high value on loyalty, discipline, teamwork, and respect for authority (Boychuk-Duchscher & Cowin, 2004). Nurses from this generation have always worked within the hierarchy of management and diversity of leadership and are accustomed to the autocratic style of leaders and managers.

The Baby Boomers

The Baby Boomers make up the largest group of nurses working today, and the majority of nurse management positions are filled by Baby Boomers. Members of this group have a multitude of family responsibilities, frequently spanning three generations. In fact, this group is frequently referred to as the “sandwich generation,” because these people are caught between caring for their children while also caring for their own aging parents. Nurses in this group are very ambitious. They put in long hours and have a strong sense of idealism, both at home and at work. Baby Boomers value what others think, and it is important that their achievements be recognized. They have set and maintained a grueling pace between their family and employment responsibilities. This group has embraced technology as a method to increase productivity and to have more free time (Cordeniz, 2003).

The individuals of the Baby Boomer generation are also most accustomed to working with autocratic leaders so they remain products of the hierarchical theory of leadership and management but are beginning to recognize and ask for some of the elements of the behavioral theory. They are also frequently challenged by nurses of younger generations, who see little value in hierarchical leadership in a system such as health care, which includes multiple groups and professions, some of whom have autonomy by licensure that is not recognized in a leadership hierarchy. By contrast, Baby Boomers are focused on building careers and are invested in organizational loyalty (Scott, 2007).

Generation X

Members of Generation X grew up in the information age; they are energetic and innovative. They are also hard workers, but unlike Baby Boomers, Gen X employees have little loyalty to, or confidence in, leaders and institutions. They value portability of their career and tend to change jobs frequently; they will stay in a position as long as it is good for them. This generation saw the downsizing of the 1990s, when organizational loyalty did not protect workers from loss of jobs or retirement. Thus they tend to have little aspiration for retirement. The use of technology has initiated an expectation of instant response and satisfaction. Technology has shaped their learning style; they want immediate answers from a variety of sources (Scott, 2007). They want different employment standards, such as opportunities for self-building and responsibility for work outcomes. They want extensive learning and precepting, and they want their questions answered immediately.

Gen X nurses value their free time; therefore, flexible scheduling and benefits (daycare centers, liberal vacations, working from home) are important. They claim to be motivated by work that agrees with their values and demands (Cordeniz, 2003). This group wants to work under motivational leadership with a democratic manager. If they do not find that kind of environment, they will have little reason to maintain employment in that institution.

Because most of the leaders and managers in health care are from the Baby Boomer generation, the conflict between these generations is certainly a significant contributor to the high turnover rate among younger nurses and the high rate of nurses finding employment outside of the hospital setting.

Generation Y

Members of Generation Y (also known as Generation Net, Nexters, or the Millennium Generation) were born between 1980 and 2000. This is the largest group, perhaps three times the size of Generation X; as such, this generation is having a formidable impact on the employment market. Those in their 20s and 30s are beginning to have an influence on how organizations are managed. This generation represents a large number of the children of the Baby Boomers. While the Baby Boomers were trying to master Windows and now the iPhone, these kids were playing with computers in kindergarten!

The impact of this generation is still being defined, but with the speed of generational changes, the impact of Generation Y may soon be integrated with the newest generation, currently labeled Generation Now. The Y Generation is smart and believes education is the key to success. For this group, diversity is a given, technology is as transparent as air, and social responsibility is a business imperative (Martin, 2004). Members of Gen Y are optimistic and interactive; yet they value individuality and uniqueness. They can multitask, think fast, and are extremely creative.

Managing this group will require a vastly different set of skills than what exists in the market today. Generation Y nurses are not team players. They are in the driver’s seat—they know that work is there for them if they want it. Focusing on understanding their capabilities, treating them as colleagues, and putting them in roles that push their limits will help managers recognize the potential of this group to become the highest producing workforce in history (Martin, 2004). This is the most educated generation ever. Gen Y employees believe that they can either “start at the top or be climbing the corporate ladder by their sixth month on the job” (NAS, 2006, p.6). They learn quickly and adapt quickly. Research by a leadership development company found that “while just 48% of millennials hold a leadership title, 72% of them consider themselves a leader in the workplace” (Fallon, 2014). The hierarchy of health care leadership and management is generally not what they are seeking as a part of their employment, because they will develop their own leadership position in whatever they are doing. How they function in the role of follower is still being determined, and the role of follower will likely be redefined by this fast-moving generation.

Generation Now or Gen Z

The newest generation is being called Generation Now, the I Generation, or Gen Z. They have never lived without the Internet and other forms of rapid communication. This means they have never known a world without immediacy (IMedia Connection, 2006). The impact of this generation is already being felt in all aspects of our society and world. The way those in Gen Now/Gen Z think, act, find information, negotiate, and make decisions may make our present theories of leadership and management obsolete and just a part of our long history. Is this part of what Leland Kaiser envisioned when he talked about transformational leadership occurring when we were ready, or does Gen Now/Gen Z represent the emergence of a new leadership theory?

The challenge to nursing will be to develop a workplace, as well as a profession, that will be attractive to all these generations, particularly those who represent the mainstream of the workforce. Equally important is consideration by nurse leaders and managers of the unique differences that exist between each generation (Critical Thinking Box 10.2). According to Lynn Wieck, who has been studying the different generations and the impact they have on nursing, “The younger nurses also want to know who, what, and why a policy was decided, and they want input into the process” (cited in Trossman, 2007, p.8). Wieck’s research has validated the generational differences and the impact these differences are having on nursing (Trossman, 2007). The key is to learn the art of compromise as these generations continue to learn to work together, calling on the wisdom of the more experienced generation and the enthusiasm of the youngest of us to demonstrate that excellent care can be provided while making the work “more ergonomic, economical and eco-friendly” (Malleo, 2010, para 9). Gen Now/Gen Z staff can show a new way to accomplish the work that is different from the task orientation of the older generations—both of which were, and are, appropriate for the system at the time. They perceive themselves to be leaders versus followers, which means management will need to do what can be done to “equalize” the perception of leaders and followers.

Initially, there must be a focus on recruiting the younger generations into the health care fields, specifically into nursing. Emphasis must also be placed on retention of experienced nurses. These nurses are necessary to mentor the younger generations, and their experience is invaluable. Eric Chester works with young people and has outlined strategies for managing and motivating the younger generations (Boxes 10.2 and 10.3). Review these strategies—they are not new, nor are they exclusive to young employees. These strategies make sense for every generation and every organization at any time (Verret, 2000) (Critical Thinking Box 10.3).

The changes in the way the younger generations relate to leadership and management may well be part of the reason more hospitals are becoming Magnet certified. Magnet is a comprehensive program relating to many aspects of nursing and nursing practice, but the basis for most of the success of the program is the acceptance of a change in the way practice is governed and controlled. Magnet facilities demonstrate a true implementation of shared governance in which the nursing staff has control of the clinical practice of nursing and practice aspects of the work environment (HCPro, 2006).

Up to this point, leadership has been considered primarily as a part of management. In 2004, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) brought a group together to develop a position of clinical nurse leader (CNL) (Stanley et al., 2008). The rationale for this position was that, with the changing health care needs of this society, the system does not seem to be “making the best use of its resources leading to a need to educate future practitioners differently” (Stanley et al., 2008, p.615). It was thought that this was critical to addressing successfully the many significant clinical issues facing the system during a time when resources are becoming limited. Having a highly prepared individual in the clinical setting is meant to impact positively the current patient safety issues by identifying and managing risk while meeting standards of quality clinical care.

As stated by Tornabeni and Miller (2008), “Improved patient care requires more nurses, better educated nurses and revised systems and environments for delivering patient care” (pp.608–609). Many factors support this need; it is known that with shorter lengths of stay and increasing complexity of care and treatment, stability in the delivery of nursing care is essential for reaching the defined outcomes of that care. This also has to be accomplished in a manner that maximizes the use of available resources while minimizing patient hand-offs and risks as these outcomes are reached. The clinical nurse leader is a master’s degree–prepared registered nurse who is expected to

▪ Improve the quality of patient care through evidence-based practices

▪ Improve communication among all team members

▪ Provide guidance for less experienced nurses

▪ Assure that the patient has a smooth flow through the health system (Stanley et al., 2008, p.618).

This role is a combination of a bedside nurse, case manager, clinical educator, and team leader. The introduction of the clinical nurse leader role also addresses a long-standing complaint about acute-care nursing practice. Within the clinical setting, the two major opportunities for advancement were to assume a management position or to become a clinical educator. Both essentially remove individuals from the bedside, which is the heart of our practice. With this new clinical role, nurses who wish to advance to a different role while providing direct patient care now have the opportunity to do so.

An example of the success of the CNL role follows. Measurable performance measures for the staff practicing on the surgical unit were identified as a part of the quality review program. These performance measures were antibiotic use and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. To effectively transform the nurses’ thought processes and gain buy-in to this performance improvement, the need for a cultural change was identified. A clinical nurse leader was made available to assist the staff in understanding the need for this change and the benefits that would come about after this change was implemented. The CNL is a transformational leader who uses more than one style of leadership to motivate his or her employees to perform at a level of excellence. The styles of leadership used to adequately improve the performance on the surgery unit were affiliative and democratic (Landry, 2000–2016).

Power and Authority in Nursing Management

Do You Know the Difference Between Power and Authority?

To have power means having the ability to effect change and to influence others to meet identified goals. Having authority relates to a specific position and the responsibility associated with that position. The individual with authority has the right to act in situations for which one is held responsible within the institutional hierarchy. This is a role most often assumed as a part of management.

What Are the Different Types of Power?

There are many different types of power, so let us discuss those that are most common. Legitimate power is power connected to a position of authority. The individual has power as a result of the position. The head nurse has legitimate power and authority as a result of the position held.

Reward power is closely linked with legitimate power in that it comes about because the individual has the power to provide or withhold rewards. If supervisors have the power to authorize salary increases or scheduling changes, then they have reward power. Coercive power is power derived from fear of consequences. It is easy to see how parents would have coercive power over children based on the threat of punishment. This type of power can also be used toward staff members when, for example, there is the threat of receiving unfavorable assignments. However, in considering the characteristics of the upcoming generations, this sort of power may not be effective with them.

Expert power is based on specialized knowledge, skills, or abilities that are recognized and respected by others. The individual is perceived as an expert in an area and has power in that area because of this expertise. For instance, the enterostomal therapist has expertise in the care of individuals who have had ostomies. Therefore, staff nurses seek out the therapist as a resource and use the expert’s knowledge to guide the care of these patients. The clinical nurse leader is another example of a nurse-expert who has responsibility to act as a resource for others.

Referent power is power that a person has because others closely identify with that person’s personal characteristics; they are liked and admired by others. Individuals who have knowledge that is needed by others to function effectively in their roles possess information power. This type of power is perhaps the most abused! An individual may, for example, withhold information from subordinates to maintain control. The leader who gives directions without providing needed information on rationale or constraints is abusing information power.

Leadership power is the “capacity to create order from conflict, contradictions, and chaos” (Sullivan & Decker, 2012). This is possible when the staff or people involved in the conflicts have a trust in that leader who is able to influence people to respond because they want to respond!

Leaders and managers need to understand the concept of power and how it can be used and abused in working with others. Nurses, on the whole, need to identify ways to increase their power within the health team. Graduate nurses need to be aware of and willing to implement methods and resources to increase their personal power. As they gain experience in the staff nurse role, they can develop expert power by increasing competency in their roles and clinical skills.

Refining interpersonal skills that enhance the ability to work with others can expand many types of power, such as information, referent, and leadership power. These skills include clearly and completely communicating information that people need to know while gaining support for work to be done either through delegating or by encouraging staff to step forward to do what’s necessary to accomplish the stated goals. Demonstrating a willingness to give and receive feedback while providing positive communication is also important when working to develop and enhance power in working with others.

It is also important to recognize what detracts from power. Impressing others as disorganized, either in personal appearance or in work habits, engaging in petty criticism or gossip, and being unable to say no without qualification are some of the behaviors that can detract from power.

Today there is much discussion in nursing about the importance of power and the concept of empowerment. To empower nurses is to provide them with greater influence and decision-making opportunities in their roles. The realization of greater power in the profession depends on the willingness of administrators to allocate this power and of nurses to accept it, along with the accompanying responsibility.

There are some people in the health care system who believe nurses are powerless—among these people are many nurses who “ feel powerless in their jobs, unable to act autonomously or even speak up about concerns or suggestions” (Garner, 2011). Part of this perception of powerlessness is related to the fact that minimal time is spent learning leadership skills and more than 50% of nurses are not educated at the baccalaureate level where most of the leadership skills are discussed and practiced.

It is essential that nurses, who spend more time than others at a patient’s bedside, feel confident in identifying “activities that can improve patient care or help the unit run more smoothly” (Garner, 2011). The growth in the number of Magnet hospitals is making a significant difference and decreasing the number of nurses who are hesitant to let their power show!

The basis for practice in Magnet-credentialed facilities is the empowerment of staff to make decisions that directly affect the practice of registered nurses who are providing direct care. This is accomplished through the development of a culture supporting the decentralization of management, power, and authority in all places in which registered nurses are providing care. A clearly delineated structure for accomplishing the appropriate decision making and clearly communicating these decisions must be in place and accessible to all registered nurses in the organization. Additionally, the responsibility for monitoring compliance and outcomes is also shared by the registered nurse staff rather than leaving this important function solely to management.

Management Problem Solving

How Are Problem-Solving Strategies Used in Management?

Management is a problem-oriented process. The effective manager analyzes problems and makes decisions throughout all the planning, organizing, directing, and controlling functions of management. Problem solving can be readily compared with the nursing process (Table 10.1). This is because the nursing process is based on the scientific method of problem solving. The two are essentially the same, as can be seen by comparing the steps of one with the other.

As with the nursing process, problem solving does not always flow in an orderly manner from one step to the next. Throughout the process, feedback is sought, which may indicate a need for altering the plan to reach the desired objective. The most critical step in either process is identifying the problem (identified as the nursing diagnosis in the nursing process). Frequently what was originally identified as the problem may be too broad or unclear. Only the symptoms of the problem may be seen initially, or there may be several problems overlapping. If an approach is used to relieve only the symptoms, the problem will still exist. The good manager will guide the process of identifying the problem by asking questions such as “What is happening?” “What is being done about it?” “Who is doing what?” and “Why?” It is important to differentiate among facts and opinions and to attempt to break down the information to its simplest terms. Think of it as being a detective looking for every clue!

TABLE 10.1

Nursing Process Versus Problem Solving

| Nursing Process | Problem Solving |

| Assessment | Data gathering |

| Analysis/nursing diagnosis | Definition of the problem |

| Development of plan | Identification of alternative solutions |

| Implementation of plan | Implementation of plan |

| Evaluation/assessment | Evaluation of solution |

After the problem is clearly identified, the group should brainstorm all possible solutions. Often the first few alternatives are not the best or most practical. Identifying a number of viable alternatives usually provides more flexibility and creativity. All possible solutions must fall within existing constraints, such as staff abilities, available resources, and institutional policies. The more complex the problem, the more judgment is required. In some cases the problem may extend beyond the manager’s scope of responsibility and authority; therefore, it may be necessary to seek outside help.

After identifying all the alternatives, each must be evaluated in relation to changes that would be required in existing policies, procedures, staffing, and so forth, as well as what effect these changes would have. Ask “What would happen if …” questions to clarify the short- and long-term implications of each alternative. Keep in mind that the perfect solution is not possible in most situations.

Problem solving represents a choice made between possible alternatives that are thought to be the best solutions for a particular situation. At its best, problem solving should involve ample discussion of the possible solutions by those who are affected by the situation and who possess the knowledge and power to support the possible solution. After an alternative has been selected, it should be implemented unless new data or perspectives warrant a change. Feedback should be sought continuously to provide ongoing evaluation of the effectiveness of the solution. Remember that simply choosing the best alternative does not automatically ensure its acceptance by those who work with it!

Evidence-Based Management Protocols and Interventions

Just as nurses are expected to practice using evidence-based protocols and interventions for clinical decision making, managers are expected to use those management practices that are based on demonstrated outcomes. This may be difficult to accomplish, because management practices are often deeply imbedded in the culture of an organization. Changing these practices to what is known to work from those that may have worked in the past may be considered as a challenge to the core philosophy of that organization.

Pfeffer and Sutton (2006) state:

If a manager is guided by the best logic and evidence and if they relentlessly seek new knowledge and insight, from both inside and outside their organizations, to keep updating their assumptions, knowledge and skills, they can be more effective.

To accomplish this, the manager needs to be able to develop a commitment to searching for, and using, processes and solutions that are factually based, leading to the ability to make decisions that lead to intended outcomes (Pfeffer & Sutton, 2006). It is believed that there is much peer-reviewed information regarding managing organizations that is not used because of the desire to do things as they have always been done—knowing that they do work some of the time.

The example provided in an article in the Harvard Business Review relates to the use of stand-up meetings versus the traditional sit-down meetings. Evidence indicates that during stand-up meetings it took 34% less time to make decisions (Pfeffer & Sutton, 2006). Using this model could save an organization many hours a year that could be put to another productive use or could be eliminated from the payroll. However, very few organizations use this model for meetings, even in the face of the clear evidence regarding the impact it would have on the organization.

Appropriate hand washing between patient encounters is a problem that has affected health care since the 1850s. The solution sounds simple—wash your hands between patient encounters—but history has demonstrated that having leaders/managers who require this solution has not been effective. Random surveys of staff in health care facilities demonstrate that rates of hand washing average “about 37.5%” (WHO in Armellino et al., 2011).

A study conducted in 2009 to 2010 by Armellino et al. used “remote video auditing with and without feedback” to determine the rate of hand hygiene among the staff in an intensive care unit (2011). The prefeedback period demonstrated a hand-hygiene rate of 10%. The visualization of performance with feedback resulted in a hand-hygiene rate of 81.6%. The evidence from this study demonstrates that staff are more compliant when they are aware they are being observed and also when they receive feedback regarding these observations.

Although this study pertained to hand hygiene, the elements of observation and feedback can be assumed to increase compliance with other aspects of practice that require minimal variation in the practice. Secondarily, one can take this evidence a bit further and correlate the infection rate in this intensive care unit during the period in which the 81.6% hand-hygiene compliance occurred. Consider what changes in patient status and hospital costs would be noted if an 81.6% hand-washing compliance resulted in a major reduction in hospital-acquired infections.

What other aspects of practice can you think of that can be measured using direct observation? Using regular feedback?

Nurses who have been prepared to practice using evidence-based clinical information may find that using these same skills and approaches to management is the norm. This will require a collaborative working relationship with the tenured management staff who may see this result in a shift of power to the staff who do use evidence-based management practices as a regular part of decision making.

Frequently, implementing the solution to a problem causes several other problems to arise. This can be avoided if the selected solutions are evidence-based and if they are tested before implementation to identify any areas that may be negatively affected by the new solution. This testing should be a formal process following the steps of a Failure-Mode-Effects-Analysis, which is meant to identify and address those risk points that may not have been evident when the solution was selected. Many of you will be given the opportunity to work with others to complete an analysis of new procedures, for example, before that new procedure is fully implemented. If problems arise after the analysis, testing, and implementation, the new problems should not be allowed to impede the implementation process. Instead, pause and consider each problem individually, solve it, and then return to the plan that was tested. The old adage “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again” is most appropriate when applying the problem-solving process, but using evidence-based solutions should keep repeat trials to a minimum. Remain positive, confident, and flexible! Let us apply the process to an actual problem.

John is the head nurse on a busy medical-surgical unit with 32 patients. Staff members have complained to him that too much time is being spent during the morning change-of-shift report. After asking questions and seeking additional information, John determines that a clearer definition of the problem is that the night charge nurse does not give a clear, concise report. Researching the peer-reviewed literature for solutions addressing end-of-shift communication and involving the night charge nurse in the problem-solving process help to define the problem. Is it because the nurse does not have adequate knowledge of how to give a change-of-shift report? Or is it a flaw in the report system that does not allow for adequate communication to occur?

Can you see how, after the problem has been clarified, it becomes more amenable to an acceptable, and perhaps even easy, solution?

How Are Problem Solving and Decision Making Related?

By definition, problem solving and decision making are almost the same process, with one very notable difference. Decision making requires the definition of a clear objective to guide the process. A comparison of the steps of each illustrates this difference (Table 10.2). Although both problem solving and decision making are usually initiated in the presence of a problem, the objective in decision making may not be to solve the problem but only to deal with its results. It is also important to distinguish between a good decision and a good outcome. A good outcome is the objective that is desired, and a good decision is one made systematically to reach this objective. A good decision may or may not result in a good outcome. Although it is desirable to have both good decisions and good outcomes, the good decision maker is willing to act, even at the risk of a negative outcome.

TABLE 10.2

Problem Solving Versus Decision Making

| Problem Solving | Decision Making |

| Define problem | Set objective |

| Identify alternative solutions | Identify and evaluate alternative decisions |

| Select solution and implement | Make decision and implement |

| Evaluate outcome | Evaluate outcome |

Susan is the evening charge nurse on a medical unit that has a total of 24 patients. One of the patients is terminally ill and seems to be having a particularly difficult evening. The patient requires basic comfort measures but little complex care. Susan has a choice of assigning the patient to another RN or delegating care to a nursing assistant. If she assigns the RN, the workload for the other staff will be heavier, and she herself will be assigned to the terminally ill patient, to provide the care that cannot be delegated to the nursing assistant. Susan decides to assign the RN, because this patient requires the emotional and physical support best provided by an RN. During the shift, the RN spends time sitting with the patient. Close to the end of the shift, the patient dies. Was this a good decision with a bad outcome or a good decision with a good outcome?

Decision making is values-based, whereas problem solving is traditionally a more scientific process. Efforts to acquire evidence-based information as one is identifying alternative solutions to problems move the decision making process into the scientific arena. Nurses will continue to make decisions based on personal values, life experiences, perceptions of the situation, knowledge of risks associated with possible decisions, and their individual ways of thinking, but these factors will be influenced by the availability of information and solutions that have been scientifically tested. Because of these variables, two individuals given the same information and using the same decision-making process may arrive at different decisions, but the probability should be lower after evidence-based information is available.

In today’s ever-changing health care environment, it is important for nurses and nurse managers to be effective in both problem solving and decision making. The good manager will evaluate the problem-solving or decision-making process based on criteria that provide a view of the big picture. These criteria include the likely effects on the objective to be met, on the policies and resources of the organization, on the individuals involved, and on the product or service delivered.

The quality of patient care is dependent on the ability of the nurse to effectively combine problem solving with decision making. To do so, nurses must be attuned to their individual value systems and understand the effect of these systems on thinking and perceiving. The values associated with a particular situation will limit the alternatives generated and the final decision. For this reason, the fact that nurses typically work in groups is beneficial to the decision-making process. Although the process is the same, groups generally offer the benefits of a broader knowledge base for defining objectives and more creativity in identifying alternatives. It is important for nurses to understand the roles of individuals within the group and the dynamics involved in working in groups to take full advantage of the group process. Chapter 11 focuses on communication, group process, and working with teams.

What Effect Does the Leader Have on the Group?

The leader’s philosophy, personality, self-concept, and interpersonal skills all influence the functioning of the group. A leader is most effective if members are respected as individuals who have unique contributions to make to the group process. Can you remember our earlier discussion of the characteristics of a good leader? The ability to influence and motivate others is particularly important in the group process.

Whenever the combination of people in a group is altered, the dynamics are changed. If the group is in the working phase, it will revert to the initiating phase when a new person or persons are added and will remain there until they have been assimilated into the group and a new dynamic has been formulated. The most effective groups are those that have had consistent membership and are highly developed. These groups demonstrate friendly and trusting relationships; the ability to work toward goals of varying difficulty; flexible, stable, and reliable participation of members; and productivity with high-quality output. Leadership within these groups is democratic, and the members feel positive about their participation and the outcomes of the group process. Now let us apply these principles to a real situation!

When you graduate and accept a nursing position, you will become a new nurse in the work group, causing it to regress to the initiating phase. This is your opportunity to demonstrate to the members of the group that you are worthy of being included in the group. If this is your first nursing position, you will also demonstrate to the group that you are worthy of entering the nursing profession. During this time, you may experience feelings of loneliness, isolation, and distance that accompany the initiating phase. However, your feelings of pride, excitement, eagerness, and accomplishment should quickly eradicate those feelings of distance, because there is much to gain and much to offer when entering a new group with common goals.

Put your energy into forming supportive professional relationships, including the social aspects of these relationships. Seek and use feedback, and ask for help in areas that are not as familiar to you, such as priority setting. As you contribute your individual talents to the group, you will move from being a dependent new person to full group membership. It is important that you do not underestimate the length of time that may be needed to accomplish this task! Group processes proceed very slowly in some cases, and it may be 6 months or more before you are accepted as a full member of the work group. Do not be discouraged! Instead, use this opportunity to gain information regarding what you can offer to the next new member of the group and what you can do to make transitioning from school to practice a positive experience.

Management skills come with experience in nursing, so do not be too hard on yourself during the transition phase. Identify experienced staff nurses who are effective at managing the care of their assigned patients, and identify nurse managers who have the skills you would like to incorporate into your management style. Look at the positive side of working with staff nurses and various nursing managers as a means to assist you in the development of your personal management style. Develop the ability to think like a manager as you perform your assignments—always look at the big picture.

The Challenge Of Change

How many times have you heard staff nurses complain about how powerless they feel about the lack of control they have over their work environment? They say they are frustrated with the amount and quality of patient care they are able to deliver and that staffing patterns are placing undue stress on them. Some will talk about leaving the acute-care environment to try some other aspect of nursing (perhaps home health) as a less stressful option. Why do they run from finding a situation, rather than thinking about how they can act to change it? Do they feel powerless to do so? Is it easier to withdraw and escape?

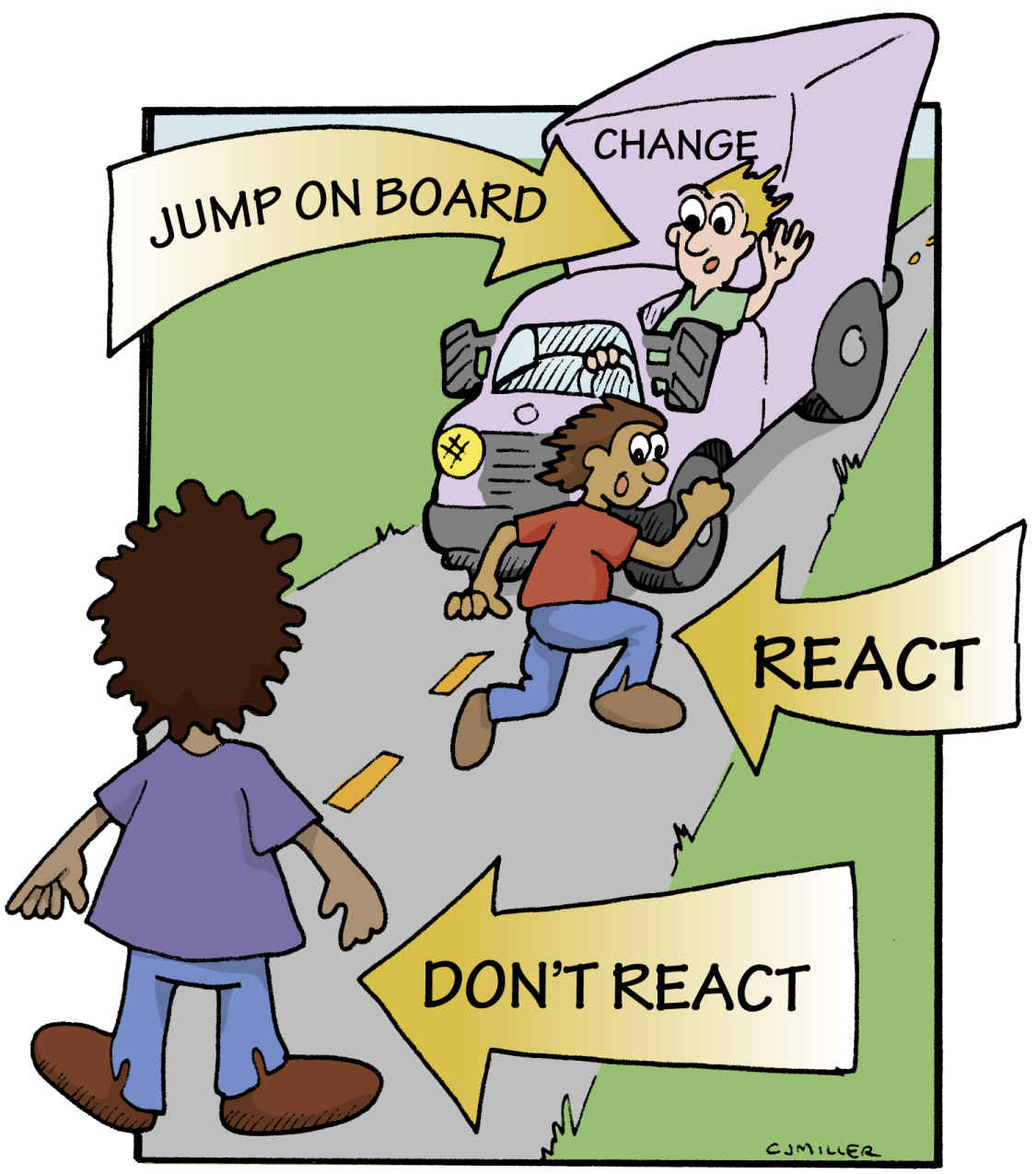

One thing we all know is that change is inevitable, particularly in today’s health care delivery system. Economic factors have taken center stage, and cutbacks in all aspects of health care services are occurring. Additionally, the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act of 2010 will bring changes to many aspects of health care as this act is incrementally implemented (Focus on Health Reform, n.d.). A major aspect of this act is that all Americans will have some type of health insurance coverage. Consider the kinds of changes this can bring on an almost immediate basis. Are you prepared to accept the challenges ahead while continuing to provide quality care as a part of your professional obligation? Change can be like a truck with no driver at the wheel: It moves slowly and steadily toward you (Fig. 10.2). You have three options: you can move out of the situation and perhaps miss some opportunities; you can just stand there and withdraw, doing what you are told just to avoid conflict; or you can start to run with it, jump on, and try to steer it in a positive direction.

So, how do you begin to direct the change that is on the horizon? The first thing to know about the change process is that it, too, has similarities to problem solving and the nursing process. Let us lay them out and compare the two processes (Table 10.3).

Look familiar? Maybe it is not that hard to take control and be a change agent! The first thing you need to know about the change process is that resisting change is a natural response for most people. All of us are most comfortable in our state of equilibrium, where we feel in control of what we are doing. To handle change effectively, it is important to understand that every change involves adaptation. It requires a period of transition in which the change can be understood, evaluated in light of its impact on the individual, and, one hopes, eventually embraced.

There are various reasons for people’s resistance to change, and understanding them will help you to implement the change process more effectively. Following are the most common factors that cause resistance to change:

▪ A perceived threat to self in how the change will affect the individual personally

▪ A lack of understanding regarding the nature of the change

▪ A limited ability to cope emotionally with change

▪ A disagreement about the potential benefits of the change

▪ A fear of the impact of the change on self-confidence and self-esteem

Kurt Lewin (1947) sought to incorporate these concepts in his Change Theory. He identified three phases in an effective change process: unfreezing, moving, and refreezing. In the unfreezing phase, all of the factors that may cause resistance to change are considered. Others who may be affected by the change are sought out to determine whether they recognize that a change is needed and to determine their interest in participating in the process. You will need to determine whether the environment of the institution is receptive to change and then convince others to work with you.

TABLE 10.3

Nursing Process Versus Change Process

| Nursing Process | Change Process |

| Assessment | Recognition that a change is needed; collect data |

| Identification of possible nursing diagnoses | Identification of problem to be solved |

| Selection of nursing diagnosis | Selection of one of possible alternatives |

| Development of plan | Implementation of plan |

| Implementation of plan | Implementation of plan |

| Evaluation | Evaluation of effects of change |

| Reassessment | Stabilization of change in place |

The moving phase occurs after a group of individuals has been recruited to take on responsibilities for implementing the change. The group begins to sort out what must be done and the sequence of actions that would be most effective. The group identifies individuals who have the power to assist in making the plan succeed. (What types of power would be most effective?) The group also attempts to identify strategies to overcome the natural resistance to change—and how to achieve a cooperative approach to implement the change. Once developed, the plan is then put into place.

The refreezing phase occurs when the plan is in place and everyone involved knows what is happening and what to expect. Publicizing the ongoing assessment of the pros and cons of the plan is an important part of its ultimate success. Be certain someone is responsible for continuing to work on the plan so that it does not lose momentum. Finally, make the changes stick—or refreeze. This will make the change a part of everyday life, and it will no longer be perceived as something new. Now let us apply this process to a real situation!

Patti is working in a medical-surgical unit at a 200-bed acute-care hospital. She constantly hears her peers complaining about the lack of adequate nursing staff, and during the previous 3 months, two full-time staff nurses have resigned. To cover the unit, part-time staff from temporary agencies and from the hospital staffing pool are being used to supplement the remaining regular staff. Because these staff members have little orientation to the unit and are frequently assigned where they are needed the most, the continuity of care and a potential for increased errors in patient care became a major concern.

Rather than continuing to complain about the situation or considering leaving, Patti decided to act and try to steer the change truck. She approached a few of the nurses and initiated a discussion about the changes in staffing and how scheduling had become a nightmare for the charge nurse. She enlisted the support of several members of the staff to begin problem solving possible solutions. They agreed that increased staffing was probably not a possible immediate solution and agreed to work within the constraints that they had.