Challenge

Chronic Eosinophilic Pneumonia

Jeong YJ, Kim K, Seo IJ, et al: Eosinophilic lung diseases: a clinical, radiologic, and pathologic overview. Radiographics 27:617-637, 2007.

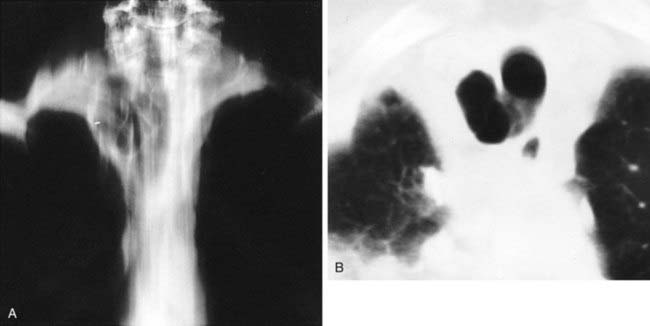

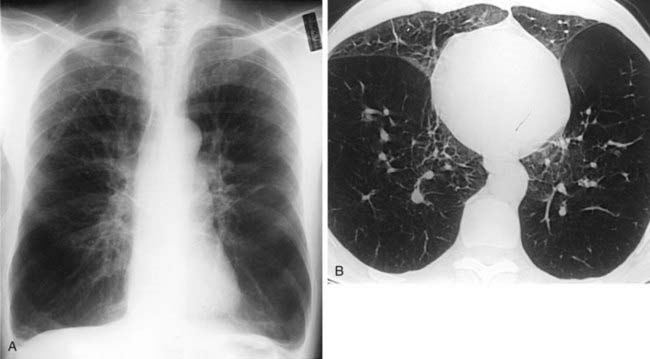

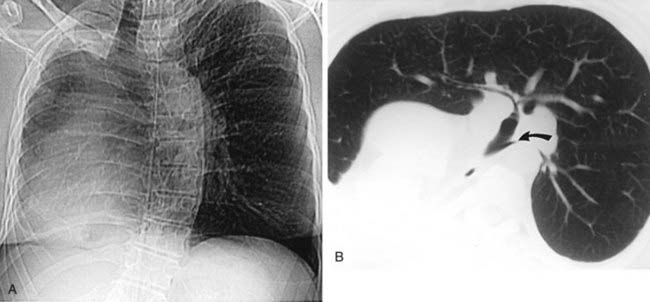

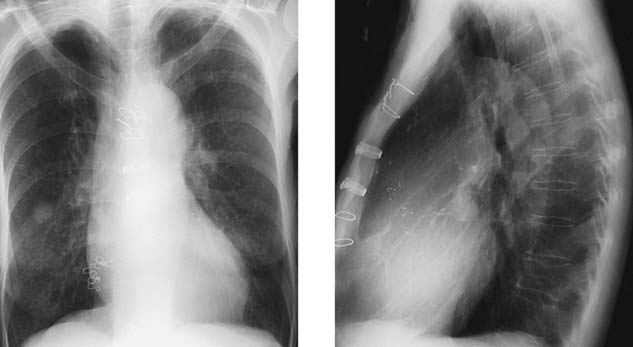

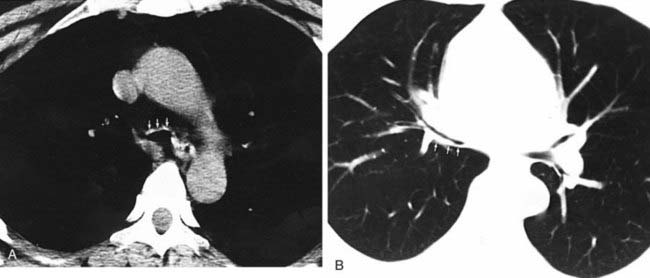

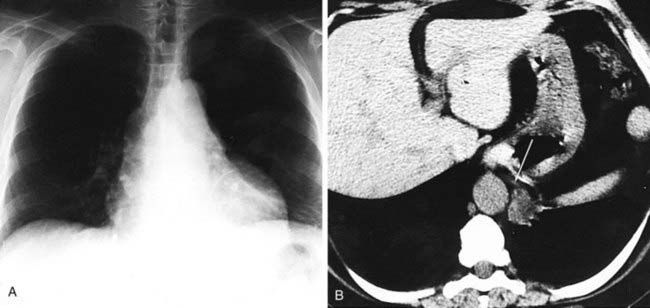

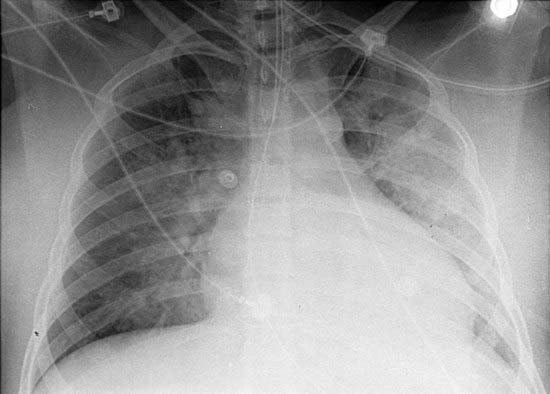

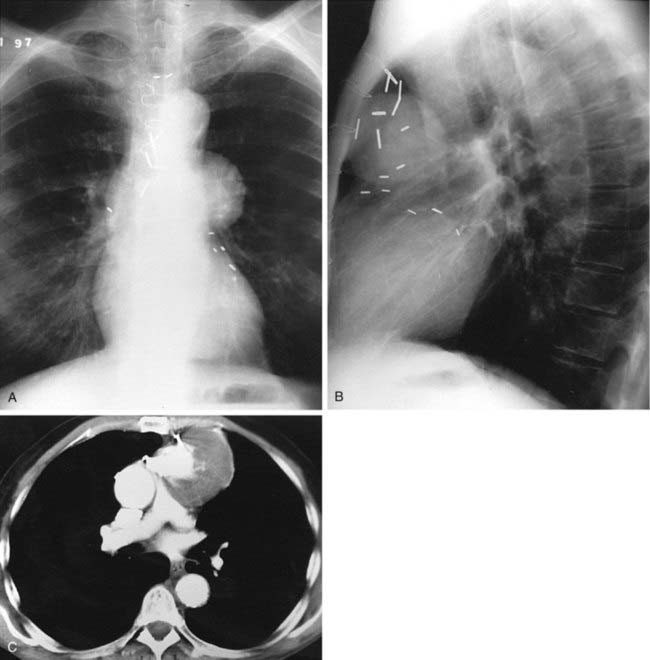

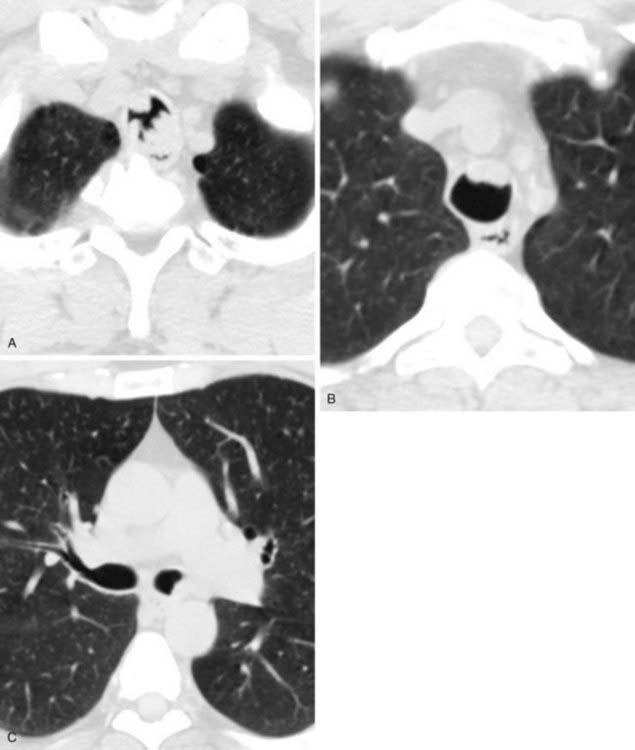

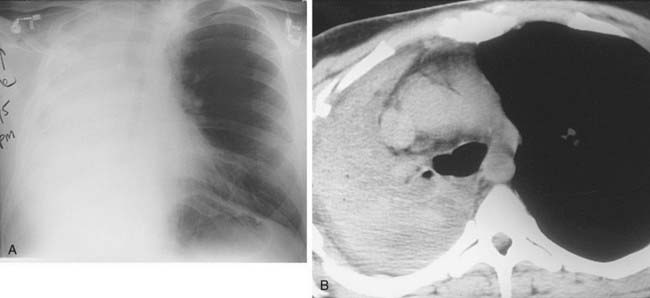

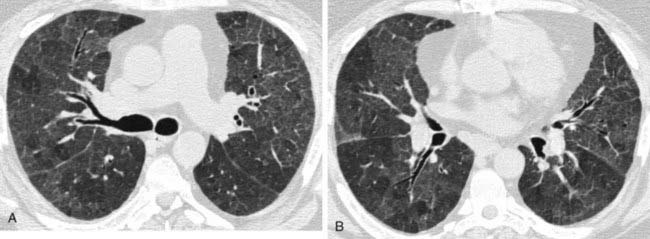

The chest radiograph in this case demonstrates multifocal areas of consolidation in both lungs, with a striking peripheral predominance in the upper lobes (best demonstrated on the coned-down image in the second figure). The distribution is typical of chronic eosinophilic pneumonia.

Affected patients typically present with symptoms of dyspnea, fever, chills, night sweats, and weight loss. Symptoms are usually present for an average of nearly 8 months prior to diagnosis. Women are affected more frequently than men, and there is a history of asthma in about one half of cases. Eosinophilia is present in the majority of patients and is usually mild to moderate.

The typical radiographic appearance is a peripheral pattern of consolidation, often with an apical or axillary distribution. The lung bases are less frequently involved. Also note the presence of right basilar consolidation in the first figure. In some patients, the opacities resolve and recur in the same location. When peripheral consolidation surrounds the lungs, the pattern is referred to as a photographic negative of pulmonary edema. Pleural effusions (which are present in this case) are infrequently encountered (less than 10% of cases).

Affected patients usually show a rapid response to steroid therapy, with clinical improvement within hours and radiographic resolution within days.

Right Paratracheal Air Cyst (Diverticulum)

Buterbaugh JE, Erly WK: Paratracheal air cysts: a common finding on routine CT examinations of the cervical spine and neck that may mimic pneumomediastinum in patients with traumatic injuries. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 29:1218-1221, 2008.

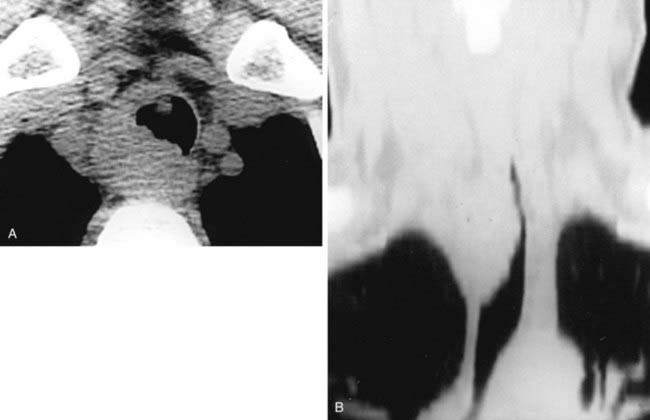

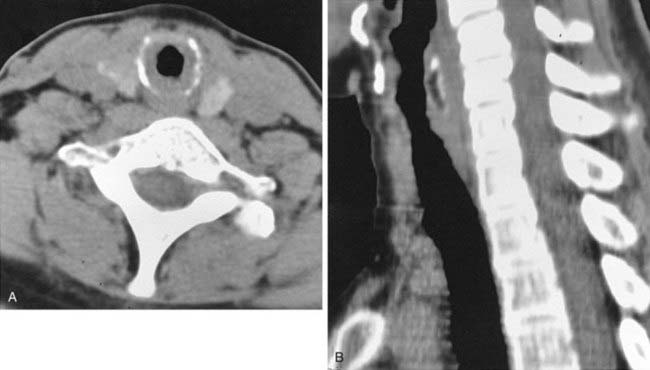

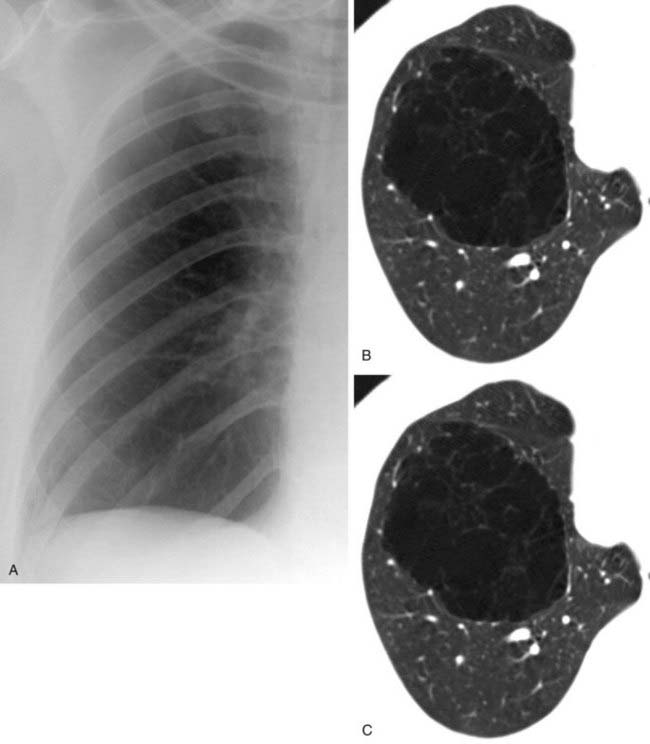

The conventional tomogram in the first figure demonstrates a well-marginated, septated cystic structure in the right paratracheal region adjacent to the right lung apex. The differential diagnosis includes a right paratracheal air cyst, apical bullae, and an apical lung hernia. The CT image in the second figure demonstrates that the cystic structure is mediastinal in location, directly communicates with the right posterolateral wall of the trachea, and does not demonstrate lung architectural features. The imaging characteristics are typical of a large right paratracheal air cyst, an abnormality of the trachea that is thought to represent a tracheal diverticulum.

Such diverticula occur most commonly at the right posterolateral wall of the trachea at the level of the thoracic inlet and vary in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. Although once considered relatively rare, small diverticula are recognized with increased frequency with modern multidetector CT (MDCT) scanners and have been reported in about 4% of neck CT scans of children and adults that included the thoracic inlet region. In the setting of trauma, a small diverticulum may potentially mimic pneumomediastinum, but its characteristic location and appearance should allow for an accurate diagnosis.

It has been proposed that acquired tracheal diverticula may occur in response to raised intratracheal pressures related to repeated bouts of coughing in patients with chronic respiratory disorders such as emphysema. However, many diverticula are considered to be congenital in etiology and are incidentally detected in both children and adults. Although usually asymptomatic, patients with diverticula may rarely present with clinical symptoms of prolonged productive cough, hemoptysis, and chest pain. Symptomatic lesions are treated surgically, but asymptomatic diverticula require no intervention.

Sternal Dehiscence Following Median Sternotomy

Boiselle PM, Mansilla AV, Fisher MS, McLoud TC: Wandering wires: frequency of sternal wire abnormalities in patients with sternal dehiscence. AJR Am J Roentgenol 173:777-780, 1999.

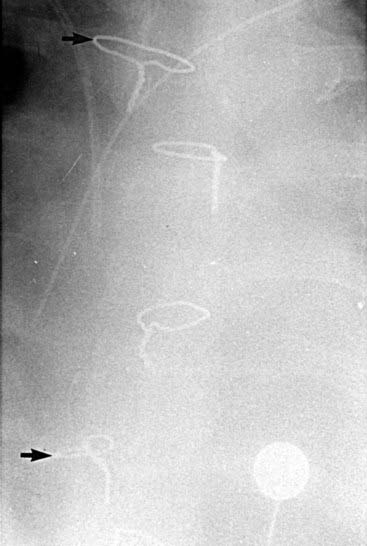

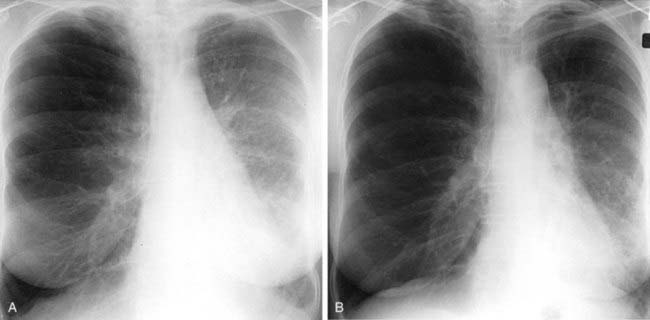

Following median sternotomy, the sternal wires are typically maintained in a vertical row along the midline of the sternum. The coned-down chest radiograph shows a scrambled arrangement of the sternal wires, with the first and fourth wires displaced to the right of the midline (arrows). Displacement of sternal wires is a highly sensitive and specific sign for sternal dehiscence, an uncommon but serious complication following median sternotomy.

Although sternal dehiscence is often evident on the basis of physical examination findings, it may be clinically occult in some cases. Sternal wire abnormalities, most notably displacement, are seen in the majority of patients with this condition; importantly, such abnormalities may precede the clinical diagnosis in some cases. Thus, when reviewing postoperative radiographs of a patient who is status post median sternotomy, you should carefully assess the sternal wires. Interval displacement or rotation of one or more wires (in comparison with their appearance on the first postoperative radiograph) should prompt careful clinical assessment for signs of dehiscence.

The high frequency of sternal wire displacement in patients with sternal dehiscence fits well with the proposed mechanism of this complication. It has been proposed that sternal separation is the result of sternal sutures pulling or cutting through the sternum rather than breaking. As the sternum separates, some sutures will travel with the right side of the sternum and others will migrate to the left side. The term wandering wires has been used to describe the characteristic alterations in sternal wires on radiographs of patients with sternal dehiscence.

Jolles H, Henry DA, Robertson JF, et al: Mediastinitis following median sternotomy: CT findings. Radiology 201:463-466, 1996.

Mediastinitis is a relatively uncommon but serious complication following median sternotomy. Mediastinitis refers to inflammation and infection of the mediastinum and is a more serious complication than superficial infection localized to the peristernal soft tissue structures of the chest wall.

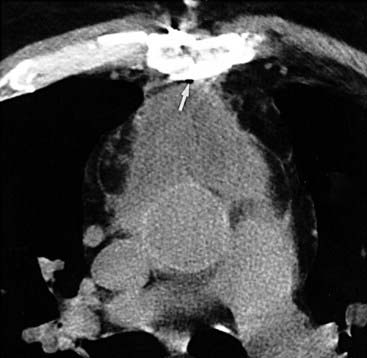

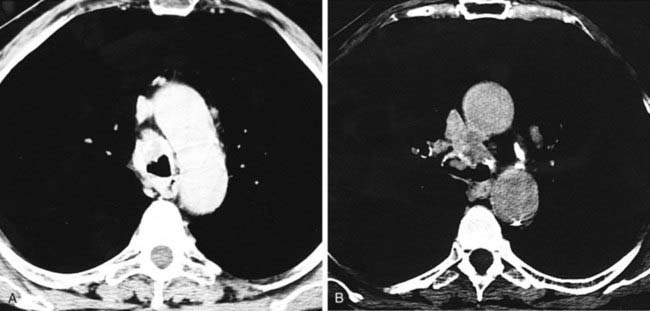

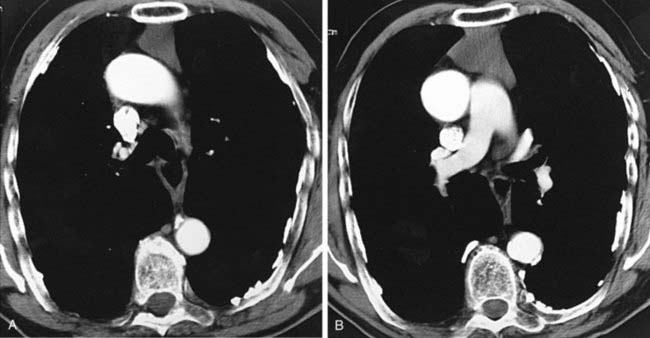

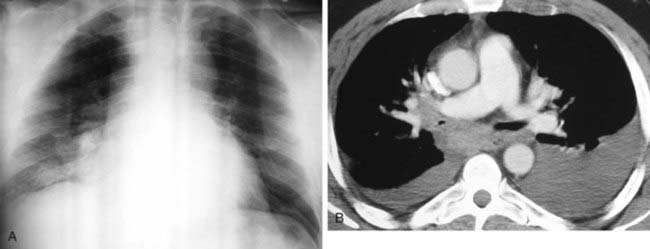

The CT diagnosis of mediastinitis is based primarily on the presence of mediastinal air and fluid collections. It is important to be aware that such findings can be seen normally in the early postoperative period in patients without mediastinitis.

In a study of patients with postoperative mediastinitis by Jolles and colleagues, it was reported that the CT findings of localized mediastinal fluid and pneumomediastinum (arrow) are highly sensitive (100%) for mediastinitis. The specificity of these findings is quite low (33%) within the first 14 days following surgery but increases significantly (100%) after postoperative day 14. Thus, when evaluating the CT scan of a postoperative patient with suspected mediastinitis, you must correlate CT findings with the time interval since surgery.

Although these data suggest that CT is most helpful in the late postoperative period, there is a role for CT imaging in the early postoperative period as well. For example, a negative CT scan of the mediastinum can be useful for directing attention to other sites of possible infection. Moreover, the identification of localized retrosternal fluid collections may be helpful for guiding aspiration procedures in patients in whom there is a strong clinical suspicion for mediastinitis.

Pulmonary Gangrene Secondary to Klebsiella Pneumonia

Tzeng DZ, Markman M, Hardin K: Necrotizing pneumonia and pulmonary gangrene: difficulty in diagnosis, evaluation and treatment. Clin Pulm Med 14:166-170, 2007.

Nosocomial pneumonia is most commonly caused by gram-negative organisms. Hospitalized patients at increased risk for nosocomial pneumonia include patients who are maintained on artificial ventilators and those who have intravenous catheters and other forms of ancillary support devices.

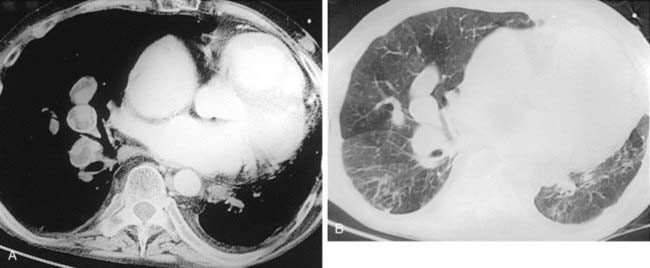

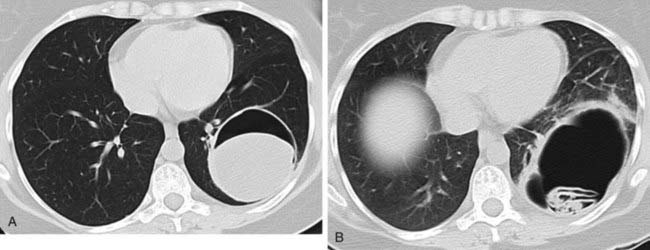

Pneumonia may be complicated by lung necrosis and cavitation, particularly when it is caused by virulent organisms. Bacteria that frequently cause cavitation include Staphylococcus aureus, gram-negative bacteria, anaerobic bacteria, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. When necrosis is extensive, arteritis and vascular thrombosis may develop in an area of intense inflammation, resulting in ischemic necrosis and death of a portion of the lung. This process may result in the presence of sloughed lung within a cavity (second figure) and is referred to as pulmonary gangrene. You should not confuse this entity with the “ball-in-cavity” appearance that is associated with the saprophytic form of Aspergillus infection. An aspergilloma develops within a long-standing, preexisting cavity. In contrast, in pulmonary gangrene, a cavity and intracavitary sloughed lung develop rapidly within an area of acute consolidation.

Although pulmonary gangrene is most closely associated with Klebsiella, it is not specific for this organism. This entity has been described in association with a variety of other organisms, including Streptococcus pneumoniae, M. tuberculosis, and Mucormycetes, among others.

Panlobular Emphysema Secondary to Intravenous Methylphenidate

Emphysema is defined by the presence of abnormal, permanent enlargement of the airspaces distal to the terminal bronchiole, accompanied by destruction of their walls without obvious fibrosis.

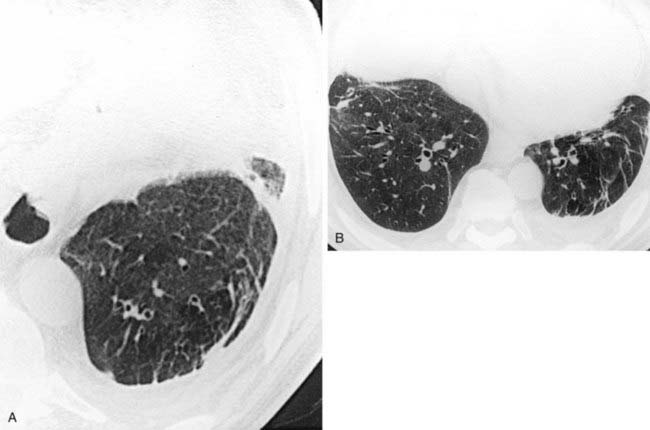

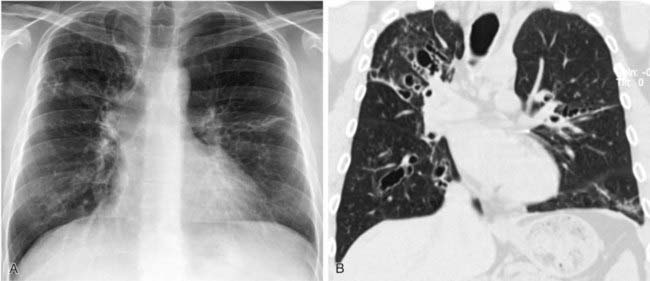

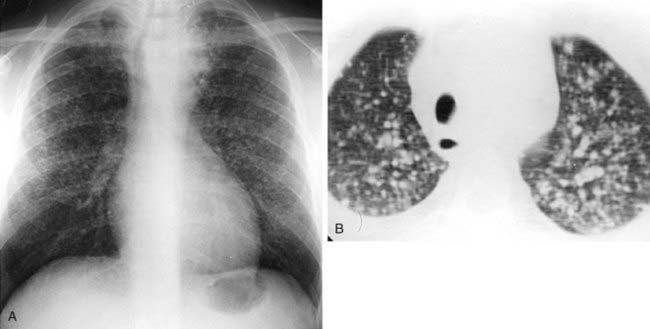

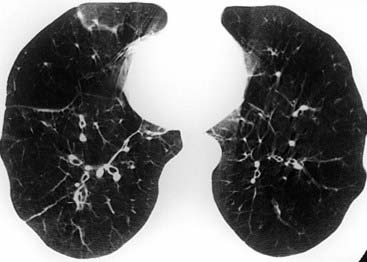

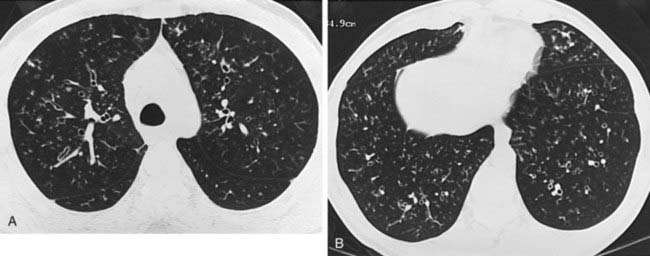

The radiograph demonstrates hyperinflation of the lungs with associated reduced vascularity in the lower lobes. The high-resolution CT (HRCT) image reveals extensive areas of abnormal low attenuation in the lower lobes with a paucity of pulmonary vessels. The CT appearance is typical of panlobular emphysema, which has been described as a “diffuse simplification of lung architecture.” Panlobular emphysema is almost always most severe in the lower lobes. In contrast, centrilobular emphysema is usually most prominent in the upper lobes.

AAT deficiency is the most common cause of panlobular emphysema with a lower lobe predominance. Intravenous drug abusers who inject methylphenidate may develop a basilar distribution of panlobular emphysema that is indistinguishable radiographically from AAT deficiency. The pathogenesis of emphysema in such patients is unknown. This condition can be distinguished from AAT deficiency by a history of methylphenidate injection, normal AAT serum levels, and pathologic evidence of microscopic talc granulomas.

Interestingly, large upper lobe bullae have been reported in individuals who regularly smoke marijuana. The mechanism is thought to involve a combination of direct pulmonary toxicity along with pleural pressure changes and airway barotrauma related to high inspiratory pressures associated with smoking marijuana.

Silva CI, Müller NL: Obliterative bronchiolitis. In: Boiselle PM, Lynch DA, Eds. CT of the Airways. Totowa NJ, Humana, 2008, pp 293-323.

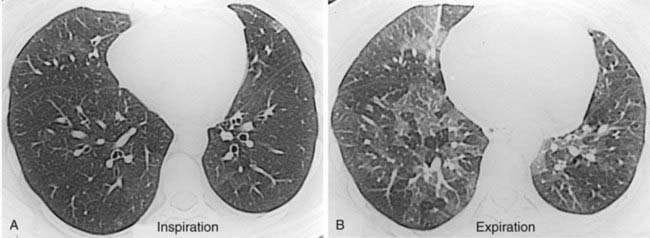

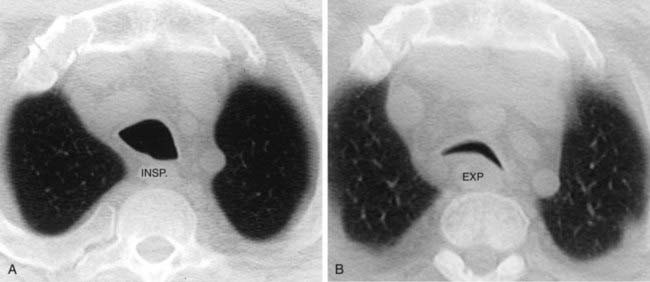

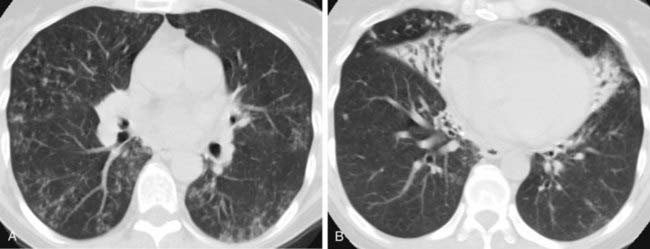

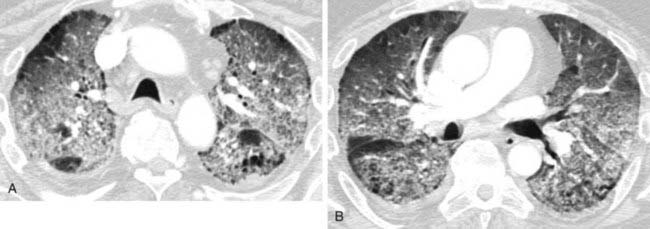

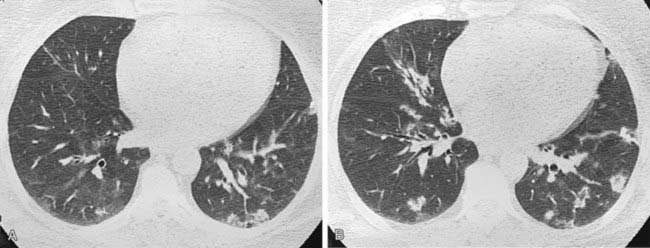

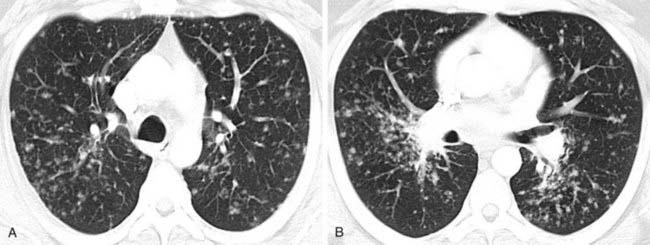

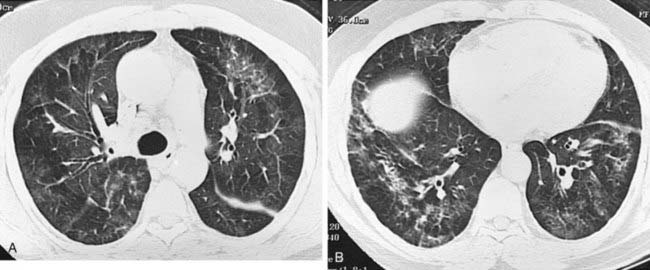

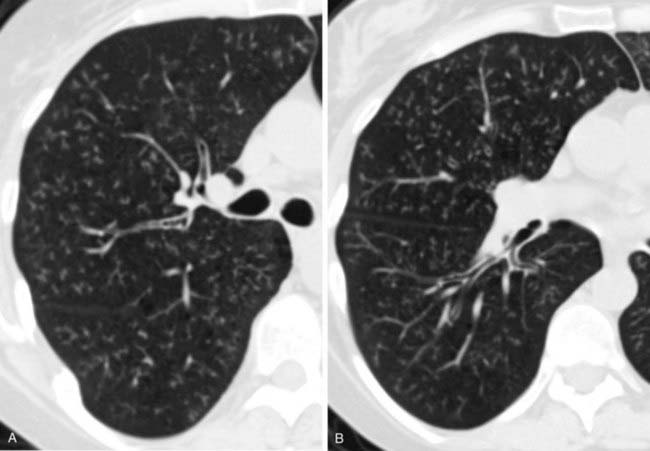

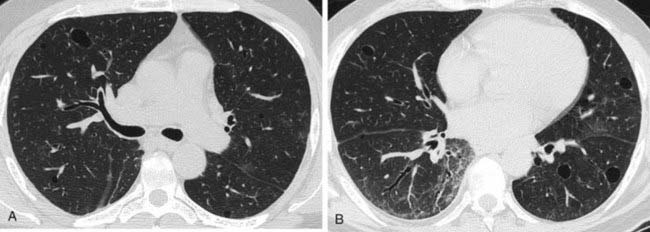

The inspiratory HRCT image in the first figure reveals a subtle pattern of variable lung attenuation, with a slight decrease in the caliber and number of pulmonary vessels within the areas of low attenuation. This appearance has been referred to as a mosaic pattern of lung attenuation and may be encountered in patients with small airways disease and pulmonary vascular abnormalities such as chronic pulmonary embolism. The expiratory HRCT image in the second figure demonstrates extensive air trapping, a finding that distinguishes small airways disease from pulmonary vascular disease.

A mosaic pattern of lung attenuation with air trapping on expiratory scans is the hallmark of OB. OB is characterized histologically by concentric narrowing of the bronchioles by submucosal and peribronchiolar fibrosis. Affected patients typically present with dyspnea. Pulmonary function tests reveal a progressive, nonreversible airflow obstruction pattern.

A variety of conditions are associated with OB, including bone marrow transplantation. Approximately 10% of bone marrow transplant patients develop OB. In such patients, this condition is thought to be related to chronic graft-versus-host disease and has a high mortality rate.

Other conditions associated with OB include childhood respiratory infections, chronic rejection following lung and heart-lung transplantation, post inhalational, ingested toxins, connective tissue disorders, drugs, inflammatory bowel disease, and a variety of miscellaneous conditions.

Abrahamson S, Gilkeson RC, Goldstein JD, et al: Benign metastasizing leiomyoma: clinical, imaging, and pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 176:1409-1413, 2001.

Pulmonary metastases are an important cause of multiple lung nodules and masses. Such nodules and masses are usually peripheral in location and have a basilar predominance.

Leiomyomas are an uncommon cause of pulmonary metastases. Other less common potential sites of involvement include lymph nodes, peritoneum, and retroperitoneal structures. The behavior of such lesions varies from that of a benign lesion to a low-grade sarcoma. Thus, the more general term metastasizing leiomyoma is preferable to the phrase “benign metastasizing leiomyoma.”

In women, these lesions may be very slowly growing metastases from a uterine leiomyoma. Affected patients often have a history of previous hysterectomy for uterine fibroids. The pulmonary lesions are usually very sensitive to hormonal therapy.

Staples CA: Computed tomography in the evaluation of benign asbestos-related disorders. Radiol Clin North Am 30:1191-1207, 1992.

Asbestosis refers to pulmonary fibrosis that occurs in asbestos workers. It usually occurs in individuals who have been exposed to high concentrations over a prolonged period. Affected patients typically present with symptoms of a dry cough and dyspnea. Pulmonary function tests reveal a progressive reduction in vital capacity and diffusing capacity.

On conventional radiographs, you may observe a linear or reticular pattern of parenchymal opacities in the lower lung zones, which may progress to honeycombing. The identification of pleural plaques or pleural thickening supports the diagnosis (note pleural thickening in the figures). However, pleural abnormalities may be absent. It is important to recognize that normal conventional radiographs do not exclude a diagnosis of asbestosis.

CT, particularly HRCT, is superior to radiography in the detection, quantification, and characterization of asbestosis. HRCT findings include (1) subpleural curvilinear lines; (2) thickened septal lines (the most common finding); (3) subpleural dependent density; (4) parenchymal bands; and (5) honeycombing. In an asbestos-exposed individual with a normal chest radiograph, these HRCT findings are suggestive of asbestosis; however, they are not specific for this process.

Shen KR, Wain JC, Wright DC, et al: Postpneumonectomy syndrome: surgical management and long-term results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 135:1210-1216, 2008.

Post-pneumonectomy syndrome is a rare, delayed complication following pneumonectomy, often performed at an early age. It is more common following right pneumonectomy than left pneumonectomy. Affected patients present with symptoms of dyspnea and recurrent infections in the remaining lung.

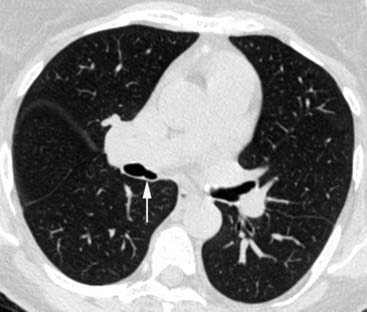

The syndrome occurs secondary to marked mediastinal shift, rotation of the heart and great vessels, and herniation of the remaining lung into the contralateral side of the chest. Following realignment of these structures, the airway may be compressed (arrow, second figure) by the thoracic spine, descending thoracic aorta, ligamentum arteriosum, and pulmonary artery.

CT plays an important role in delineating the presence and cause of airway obstruction. Inspiratory-expiratory CT may also assess for the presence of tracheobronchomalacia, an important preoperative finding. Prompt diagnosis and treatment are important, because surgical results are favorable before malacic changes have occurred within the obstructed airway.

Mounier-Kuhn Syndrome With Tracheal Diverticulum

Boiselle PM: Tracheal abnormalities: tracheomegaly. In: Müller NL, Silva CI, Eds. Imaging of the Chest. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2008, pp 1014-1017.

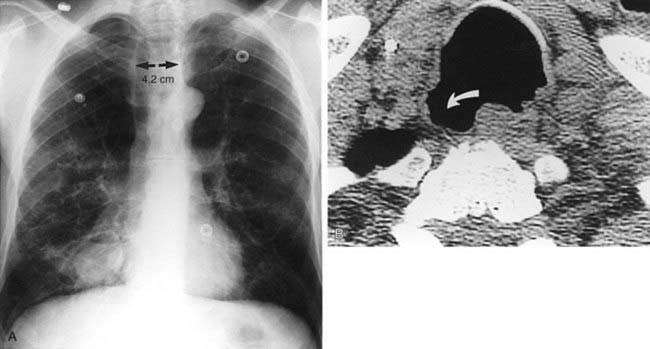

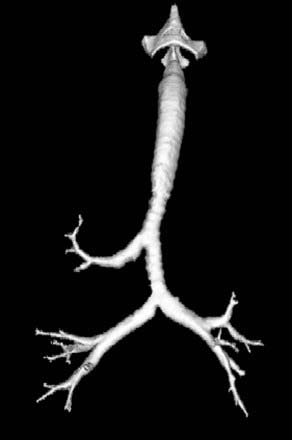

Mounier-Kuhn syndrome, also referred to as congenital tracheobronchomegaly, is characterized pathologically by atrophy or absence of elastic fibers and thinning of the muscular mucosa of the trachea and main bronchi. This results in a flaccid airway that abnormally dilates during inspiration and excessively collapses on expiration. An ineffective coughing mechanism and pooling of secretions within outpouchings of mucosa predispose affected patients to recurrent bouts of respiratory infections. Pulmonary complications include bronchiectasis, emphysema, and pulmonary fibrosis. Note the presence of tracheomegaly (note 4.2-cm-diameter coronal dimension), cystic bronchiectasis, and emphysema in the first figure.

The second figure reveals an enlarged trachea and a wide-mouthed tracheal diverticulum (curved arrow). The posterolateral wall of the trachea is the most common location for a diverticulum in patients with Mounier-Kuhn syndrome. This site represents the junction of the posterior membranous and the anterior cartilaginous portions of the trachea. A minority of patients with Mounier-Kuhn syndrome demonstrate widespread tracheal and bronchial diverticula.

Other associations with primary tracheomegaly include Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome, and cutis laxa. Secondary tracheomegaly may develop in patients with long-standing pulmonary fibrosis, possibly secondary to chronic coughing and recurrent infections.

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis

Franquet T, Müller NL, Oikonomou A, Flint JD: Aspergillus infection of the airways: computed tomography and pathologic findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr 28:10-16, 2004.

ABPA is a hypersensitivity reaction that occurs when Aspergillus organisms are inhaled by an atopic individual. The inhaled fungus grows in a noninvasive manner within the bronchi and incites an allergic response. The bronchi become dilated and filled with mucus that contains abundant eosinophils and fragmented fungal hyphae.

Affected patients typically have a history of asthma. Presenting signs and symptoms may include fever, pleuritic chest pain, expectoration of mucous plugs, and chronic cough. Radiographic features include central bronchiectasis, mucous plugging (“finger-in-glove” appearance), atelectasis, and patchy, migratory foci of consolidation.

The most characteristic imaging finding is mucous plugging. As the mucous plugs are expectorated, dilated, air-filled bronchi can be identified, especially on CT scans. The central bronchi are most commonly affected and typically demonstrate a varicoid appearance.

Because ABPA is an allergic disease, treatment consists of steroids. Chronic cases may be complicated by upper lobe scarring and bronchiectasis.

Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis

Rossi SE, Erasmus JJ, Volpacchio M, et al: “Crazy-paving” pattern at thin-section CT of the lungs: radiologic-pathologic overview. Radiographics 23:1509-1519, 2003.

PAP is characterized by filling of the alveolar spaces with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)–positive proteinaceous material, with little or no associated tissue reaction. The cause of PAP is unknown, but is has been suggested that the underlying mechanism is excessive production or impaired removal of surfactant. Although most cases are idiopathic, PAP has been reported to occur in association with an overwhelming exposure to silica and in association with immunologic disturbances.

PAP typically affects men in the fourth and fifth decades of life, and presenting symptoms include a nonproductive cough and dyspnea. Chest radiographic findings are often striking and consist of alveolar consolidation and ground-glass opacification in a symmetric, bilateral, perihilar distribution. On HRCT, ground-glass opacification predominates, and it is often patchy or geographic. A “crazy-paving” pattern is formed when smoothly thickened interlobular septal lines are superimposed on ground-glass opacification.

The prognosis of PAP has improved since the advent of therapy with BAL, which is successful in most cases. However, some patients require retreatment for relapse, and a minority of patients eventually become refractory to treatment.

Lee EY, Litmanovich D, Boiselle PM: Multidetector CT evaluation of tracheobronchomalacia. Radiol Clin North Am 47:261-269, 2009.

Tracheobronchomalacia refers to excessive collapsibility of the airway. Such collapsibility is usually most apparent during coughing and during forced expiration. The abnormally flaccid airway is associated with physiologic alterations, including an inefficient coughing mechanism and retained secretions. This may lead to recurrent infections and bronchiectasis. Rarely, it may be complicated by respiratory failure.

A primary cause of tracheobronchomalacia is congenital deficiency of cartilage. Acquired causes include prior intubation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), trauma, infection, relapsing polychondritis, and extrinsic compression (e.g., from a thyroid goiter).

Patients with severely symptomatic tracheomalacia may potentially benefit from surgery such as tracheoplasty, a technique that involves reinforcement of the posterior membranous wall of the trachea with a graft. This procedure has shown promising results in patients with acquired tracheomalacia in whom excessive tracheal collapsibility is mostly due to an abnormally flaccid posterior tracheal wall.

Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma of the Trachea

Lee KS, Boiselle PM: Tracheal and bronchial neoplasms. In: Boiselle PM, Lynch D, Eds. CT of the Airways. Totowa NJ, Humana, 2008, pp 151-190.

Primary tracheal neoplasms are quite rare. In adult patients, the majority of tracheal neoplasms are malignant. Presenting symptoms include shortness of breath and wheezing. Affected patients may be initially misdiagnosed with adult-onset asthma. This diagnosis should prompt you to carefully assess the airway on chest radiographs!

Squamous cell carcinoma has a male predilection, and it is strongly associated with cigarette smoking. Squamous cell carcinoma is associated with a poor prognosis. Therapy consists of surgery and radiation for localized disease and radiation alone for surgically unresectable cases.

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a low-grade malignancy that has no gender predilection and no relationship to cigarette smoking. Adenoid cystic carcinoma has a significantly better prognosis than squamous cell carcinoma, and surgical resection is potentially curative for patients with localized disease. Adjuvant radiation therapy is often required because of the predilection for these tumors to spread perineurally and submucosally. Late recurrences and metastases have been reported, however, especially among patients treated only with radiation therapy.

MDCT plays an important role in preoperative planning of tracheal neoplasms by determining the amenability of a lesion to complete resection and by guiding the surgeon with respect to the approach, type, and extent of resection. Multiplanar reformation and three-dimensional reconstruction images play a complementary role to axial images by enhancing the accurate assessment of the craniocaudal extent of a neoplasm and its relationship to adjacent mediastinal structures.

Mucoid Impaction Secondary to Bronchial Obstruction (Squamous Cell Carcinoma)

Martinez S, Heyneman LE, McAdams HP, et al: Mucoid impactions: finger-in-glove sign and other CT and radiographic features. Radiographics 28:1369-1382, 2008.

Mucoid impaction manifests on imaging studies as tubular or branching tubular Y- and V-shaped opacities, sometimes described as resembling a “finger-in-glove” appearance. Mucoid impaction is most often associated with ABPA and cystic fibrosis. It is important to be aware that mucoid impaction can also occur distal to a bronchial obstruction from both malignant (e.g., lung cancer, bronchial carcinoid) and benign (e.g., tuberculosis [TB] bronchostenosis) etiologies. In such cases, the affected portion of the lung remains aerated secondary to collateral air drift through interalveolar connections (pores of Kohn) and bronchiole-alveolar connections (canals of Lambert).

Detection of a tubular opacity on chest radiography should prompt consideration of both mucoid impaction and arteriovenous malformation as potential diagnoses. They can usually be distinguished on CT scans by assessing the bronchi, that is, in cases of arteriovenous malformation a normal bronchus may be observed adjacent to the tubular opacity. In some cases, low CT density numbers (–5 to +20) can confirm the diagnosis of mucoid impaction. If the diagnosis remains in doubt, contrast-enhanced CT can readily differentiate between these entities, because only an arteriovenous malformation enhances with contrast.

Localized Fibrous Tumor of the Pleura

Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Abbott GF, McAdams HP, et al: From the archives of the AFIP: localized fibrous tumor of the pleura. Radiographics 23:759-783, 2003.

Localized fibrous tumors of the pleura (synonym: solitary fibrous tumors) are uncommon primary pleural neoplasms. Histologically, approximately 60% are benign and 40% are malignant. However, all lesions are associated with a good prognosis, and the majority are curable by surgical resection.

Affected patients typically present in the sixth to seventh decades of life. In approximately 50% of cases, the patients are asymptomatic. Large lesions may produce symptoms such as cough, dyspnea, and chest pain. In a small minority of cases, patients may present with extrapulmonary manifestations, including hypertrophic osteoarthropathy and episodic hypoglycemia.

On chest radiographs, localized fibrous tumors of the pleura typically appear as round or lobulated masses that may have incomplete borders. Such masses vary in size and typically demonstrate a slow growth rate. Lesions attached to the visceral pleura by a pedicle may demonstrate mobility in response to changes in respiration and alterations in patient positioning.

On CT, small fibrous tumors of the pleura are typically homogeneous in attenuation, whereas larger tumors are often heterogeneous, particularly when imaged with contrast enhancement. On MRI, these lesions typically demonstrate low signal intensity on all sequences, reflecting the fibrous content within the stroma of the tumor, but larger tumors may manifest with increased signal on T2W images.

Solitary Pulmonary Nodule Secondary to Nocardia Infection in a Heart Transplant Patient

Haramati LB, Schulman LL, Austin JHM: Lung nodules and masses after cardiac transplantation. Radiology 188:491-497, 1993.

Cardiac transplantation is currently a widely accepted treatment for end-stage heart disease. The most common causes of morbidity and mortality following heart transplantation are infection and rejection.

When you detect single or multiple lung nodules or masses in a patient who is status post heart transplantation, you should first consider infectious etiologies such as Aspergillus and Nocardia. In a series of 257 patients who underwent heart transplantation, single or multiple lung nodules or masses were detected on chest radiographs in approximately 10% of patients. Infections were the most common etiology, with Aspergillus encountered slightly more frequently than Nocardia. Aspergillus infection developed a median of 2 months following transplantation, whereas Nocardia infection developed a median of 5 months after transplantation.

The time course for susceptibility to specific organisms is similar among patients following heart and other solid organ transplants. In the first month after transplantation, bacterial nosocomial infections are most common. Between 2 and 6 months, viral and opportunistic fungal infections are most common. Once a patient is beyond 6 months posttransplantation, bacterial community-acquired pneumonias are most common.

Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder is an important noninfectious cause of lung nodules and masses that is closely associated with the Epstein-Barr virus. The incidence of this disorder is highest during the first year following transplantation, corresponding to the time of most severe immunosuppression. Lung parenchymal abnormalities are frequently accompanied by mediastinal and/or hilar lymph node enlargement, a finding that is not typically associated with Aspergillus and Nocardia infections.

Chronic Pulmonary Thromboembolism

Wittram C, Maher MM, Yoo AJ, et al: CT angiography of pulmonary embolism: diagnostic criteria and causes of misdiagnosis. Radiographics 24:1219-1238, 2004.

Chronic pulmonary thromboembolism is a relatively uncommon but highly treatable cause of pulmonary artery hypertension. Because many affected patients do not present with a history of prior embolic episodes, the diagnosis may be difficult to make clinically.

Helical CT is playing an increasingly prominent role in the diagnosis of chronic pulmonary thromboembolism. Characteristic findings have been described in the lung parenchyma and pulmonary vessels. With regard to the lung parenchyma, you may observe variable areas of lung attenuation, with a lobular or multilobular distribution, referred to as a mosaic attenuation pattern. In the second figure, note that the low-attenuation areas of the lung have a diminished number and size of vessels compared with adjacent areas of higher attenuation. In patients with chronic pulmonary thromboembolism, this pattern reflects the diminished blood flow to areas of the lung distal to chronic emboli.

The vascular hallmark of chronic pulmonary thromboembolism is the presence of a mural thrombus. Chronic thrombus is typically adherent to the vascular wall, and it may contain foci of calcification. In patients with chronic pulmonary thromboembolism, you may also observe complete occlusion of a vessel that is smaller than its peers; a peripheral intraluminal defect; contrast flowing through thickened, often smaller, arteries due to recanalization; and a web or flap within a contrast-filled artery. In addition, extensive bronchial collateral vessels may also be observed.

Complete Lung Collapse Secondary to an Endobronchial Lesion (Lymphoma)

Müller NL, Silva CIS: Atelectasis. In: Silva CIS, Müller NL, Eds. Imaging of the Chest. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2008, pp 116-135.

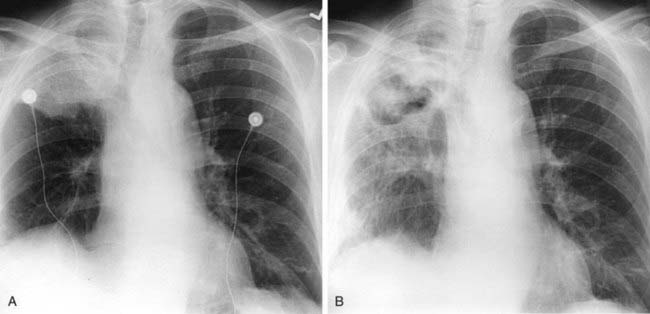

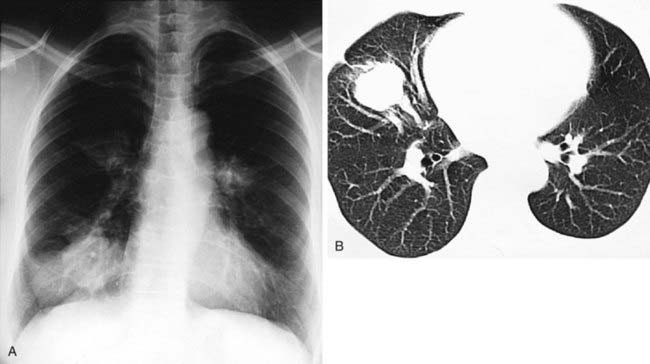

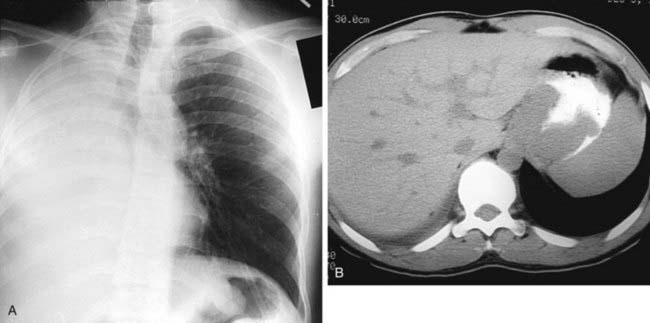

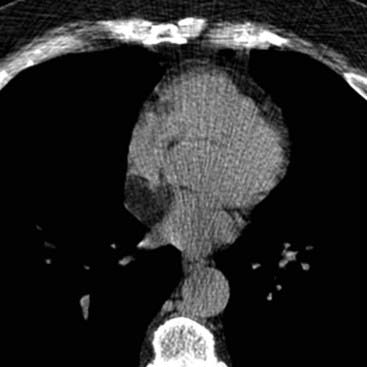

Complete opacification of a hemithorax on chest radiography is most commonly caused by complete atelectasis of the underlying lung or by a large ipsilateral pleural effusion. These entities can be readily differentiated by assessing the position of the mediastinum. When atelectasis is the primary abnormality, the mediastinum will be shifted toward the side of opacification. In contrast, when a large pleural effusion is present, the mediastinum will typically be shifted in the opposite direction. In cases of postobstructive atelectasis from an endobronchial lesion, an endobronchial filling defect may be apparent, as seen in the first figure.

Postobstructive atelectasis of an entire lung may occur secondary to a variety of causes. In the intensive care unit (ICU) setting, the presence of an obstructing mucous plug or a malpositioned endotracheal tube (e.g., right mainstem bronchus intubation) should be considered. In an outpatient setting, an obstructing neoplasm or a foreign body (more common in children than in adults) is the most likely etiology. The combination of an endobronchial lesion and gastric wall thickening may occur secondary to lymphoma or breast cancer. Although an endobronchial lesion is a rare manifestation of lymphoma, it is the best choice for the combination of imaging findings in this young adult man.

Reed JC: Diffuse fine nodular opacities. In: Chest Radiology: Plain Film Patterns and Differential Diagnoses, fifth edition. Philadelphia, Mosby, 2003, pp 287-303.

The radiograph and CT image demonstrate a diffuse, fine nodular pattern of parenchymal opacities. The majority of nodules are 2 to 3 mm in diameter, although a few are slightly larger. The small nodules are well visualized on the radiograph because they are calcified.

Although there are a variety of causes of a fine nodular pattern, only a few entities result in calcified nodules. These entities include healed varicella, healed histoplasmosis, silicosis, and calcified metastases.

With the exception of osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma, detectable calcification in metastases is unusual. A variety of mucinous and papillary neoplasms may rarely result in calcified metastases. Thyroid carcinoma is the most common cause of a fine nodular pattern of calcified metastases.

An important ancillary finding in this case is the presence of a superior mediastinal mass, with associated compression and deviation of the trachea. Such masses are usually related to the thyroid gland. In this patient, the mass represents thyroid carcinoma, and the calcified nodules are secondary to metastases.

Castleman’s Disease (Benign Lymph Node Hyperplasia)

Aster JC, Brown JR, Freedman AS: Castleman’s disease. In: Rose BD, Ed. UpToDate. Waltham, MA, UpToDate, 2009.

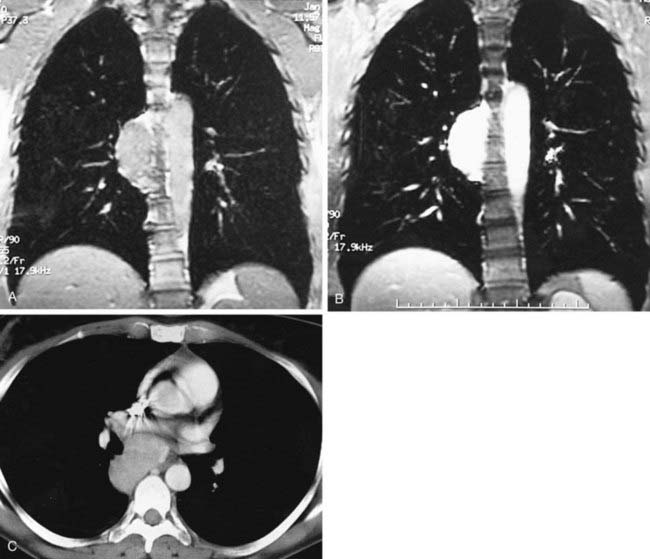

Pregadolinium and postgadolinium coronal MRIs in the first and second figures and a contrast-enhanced CT image in the third figure demonstrate an enhancing nodal mass in the subcarinal region that extends into the azygoesophageal recess. The identification of enhancing nodes significantly narrows the wide differential diagnosis of mediastinal lymph node enlargement. In a majority of cases, enhancing nodes are due to metastatic disease from hypervascular neoplasms such as renal cell, thyroid carcinoma, melanoma, and carcinoid neoplasms. The most common benign etiology is Castleman’s disease, the diagnosis in this case, which is an additional important diagnosis to consider when you identify markedly enhancing lymph nodes.

Castleman’s disease, also referred to angiofollicular benign lymph node hyperplasia, is an uncommon lymphoproliferative disorder. This disorder has been divided into two major histologic subtypes: hyaline vascular and plasma cell. The hyaline vascular subtype is present in the vast majority (90%) of cases. This subtype is characterized by hyperplasia of lymphoid follicles with germinal center formation and the presence of numerous capillaries with hyalinized walls. It usually manifests as a solitary hilar or mediastinal enhancing nodal mass in asymptomatic patients and is generally curable with surgical resection.

The plasma cell subtype is characterized by the presence of mature plasma cells between the hyperplastic germinal centers and relatively few capillaries. This form is frequently associated with clinical symptoms, including fever, fatigue, anemia, polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, and bone marrow plasmacytosis. In contrast with the hyaline vascular subtype, bilateral hilar and multifocal mediastinal lymph node enlargement is commonly observed. Another differentiating feature is the relatively low level of enhancement of nodes observed in the plasma cell subtype compared with the marked enhancement of nodes in the hyaline vascular subtype.

Castleman’s disease may also be categorized as either unicentric or multicentric in distribution. The former is usually due to the hyaline vascular subtype and the latter is usually secondary to the plasma cell variety. Importantly, multicentric Castleman’s disease carries a much worse prognosis than the unicentric variety. Although both varieties may be complicated by development of lymphoma, this is much more common in the multicentric form.

Thrombosed Saccular Aortic Aneurysm

Gilkeson RC, Kolodny S: Thoracic aorta. In: Haaga JR, Dogra VS, Forsting M, et al, Eds. CT and MRI of the Whole Body, fifth edition. Philadelphia, Elsevier Mosby, 2009, pp 1095-1098.

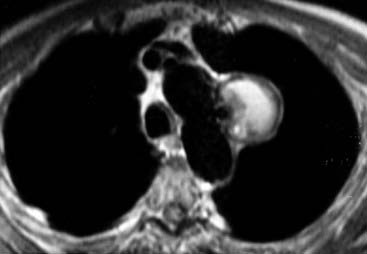

The MRI demonstrates a middle mediastinal mass that contacts the lateral aspect of the aortic arch. Whenever you identify a mass immediately adjacent to the aorta, you should always consider an aneurysm. In most cases, the vascular nature of a mass can be readily confirmed by contrast-enhanced CT or MRI.

Vascular imaging with MR historically employed both “black blood” and “white blood” imaging techniques for depiction of aortic anatomy and blood flow, respectively. Black blood imaging, as shown in this case, refers to spin-echo sequences. Such sequences result in signal void (black blood) from flowing blood within vascular structures. Although such techniques are excellent for demonstrating the anatomy of vascular structures, including vascular walls and luminal diameter, they are not ideal for assessing luminal flow. In contrast, white blood techniques are preferable for assessing luminal flow. There are a variety of white blood techniques, including cine gradient-echo (GRE), two-dimensional segmented time-of-flight, two-dimensional gadolinium-enhanced rapid GRE imaging, and gadolinium-enhanced three-dimensional angiography. These white blood techniques can readily differentiate slow flow from thrombus.

Several newer MRI techniques, including fast imaging with steady-state precession (FISP), optimized k-space filling strategies, parallel imaging techniques, and time-resolved imaging methods, have further improved the ability to assess the aorta using MRI.

This case is challenging. Note the black blood appearance of the aorta in contrast with the increased signal within most of this paraaortic mass. It is important to be aware that slow flow within vascular structures may result in increased signal intensity on T1W images.

An important clue to the diagnosis of this paraaortic mass is the identification of a small, round focus of signal void medially, which connects with the adjacent aortic lumen. Thus, this mass represents a saccular aortic aneurysm. The high signal intensity within the majority of the mass can be explained by either extensive thrombosis or slow flow. A conventional thoracic aortogram confirmed the presence of a thrombosed saccular aortic aneurysm.

Lee KS, Sun MRM, Ernst A, et al: Relapsing polychondritis: prevalence of expiratory CT airway abnormalities. Radiology 240:565-573, 2006.

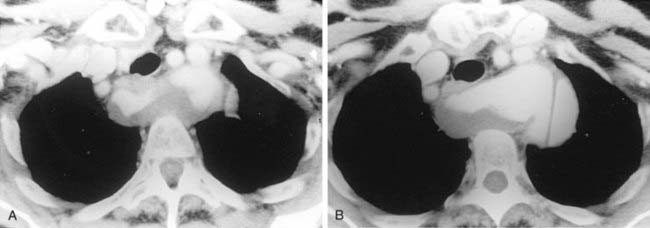

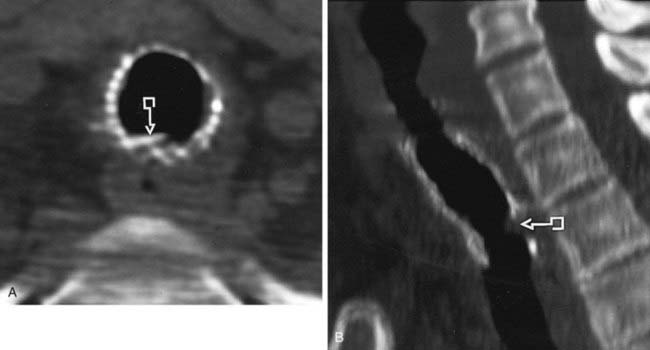

The CT images in this case demonstrate diffuse narrowing of the trachea (first figure) and bronchi (second figure), with associated thickening of the tracheal and bronchial walls (arrows). As listed in Answer 2, there are a variety of causes of diffuse tracheobronchial narrowing.

Relapsing polychondritis is a rare inflammatory disease that affects cartilages of the ears, nose, upper respiratory tract, and joints. The etiology of this condition is uncertain, but it is likely an autoimmune disorder. Recurrent bouts of inflammation result in fragmentation and subsequent fibrosis of cartilaginous structures. Auricular chondritis is the most common manifestation of this disorder, occurring in approximately 90% of patients. Respiratory tract involvement is seen in approximately 50% of patients and is the major cause of morbidity associated with this condition.

With regard to airway involvement, the larynx, trachea, and mainstem bronchi are most commonly affected. Segmental and subsegmental bronchi are affected less frequently. Initially, airway narrowing results from mucosal edema. Later in the course of this condition, edema is replaced by granulation tissue and fibrosis. Airway involvement results in impaired clearance of secretions that may be complicated by recurrent respiratory infections and bronchiectasis. Recently, there has been increasing recognition of the presence of tracheobronchomalacia in patients with relapsing polychondritis. This may occur prior to development of morphologic abnormalities in some patients. Thus, imaging evaluation of patients with suspected airway involvement from relapsing polychondritis should include both end-inspiratory and dynamic expiratory sequences. Dynamic expiratory CT imaging refers to the acquisition of a volumetric CT dataset during forced exhalation and has been shown to be more sensitive for detecting malacia than the less physiologic method of end-expiratory imaging.

Silva CT, Müller NL: Broncholitis. In: Müller NL, Silva CI, Eds. Imaging of the Chest. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2008, pp 1090-1092.

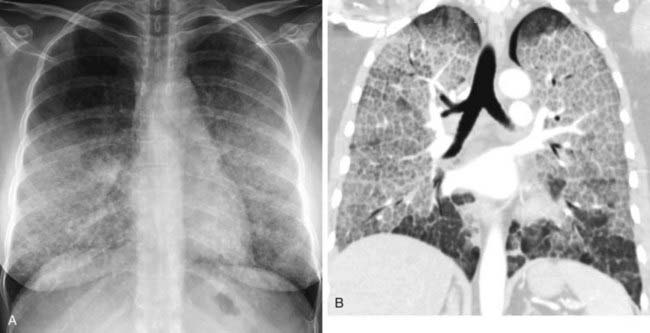

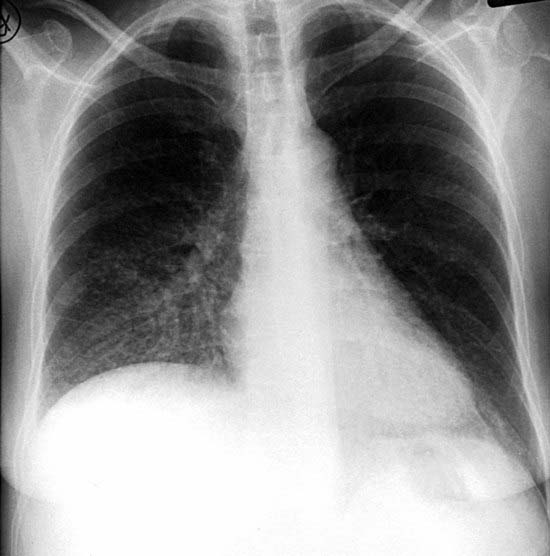

The chest radiograph demonstrates hyperlucency of the left lung with associated reduced pulmonary vascularity, which is most marked in the left lower lobe. Also note the slightly reduced size of the left lung compared with the right lung.

The imaging findings are characteristic of Swyer-James syndrome, a variant of postinfectious OB. This syndrome occurs secondary to an acute viral bronchiolitis in early infancy or early childhood that prevents the normal development of the affected lung. As shown in this case, the typical inspiratory radiograph findings include a unilateral hyperlucent lung or lobe with normal or reduced volume and reduced pulmonary vascularity. Expiratory radiographs (not shown) reveal air trapping.

HRCT imaging features of Swyer-James syndrome include (1) areas of decreased lung attenuation with associated reduction in the number and size of vessels; (2) bronchiectasis; and (3) air trapping on expiratory images. Interestingly, although radiographic findings in patients with Swyer-James syndrome are typically unilateral, CT scanning often shows patchy areas of abnormality within the opposite lung as well.

Most patients are asymptomatic adults at the time of diagnosis, and the condition is often detected incidentally on a radiograph or CT performed for other reasons. Less commonly, patients present with recurrent infections or dyspnea.

Mycobacterium avium Complex (MAC) Infection

Erasmus JJ, McAdams HP, Farrell MA, Patz EF Jr: Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial infection: radiologic manifestations. Radiographics 19:1487-1505, 1999.

Nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTMB) infection is usually caused by MAC and Mycobacterium kansasii. These organisms are found in soil and water and demonstrate similar features.

NTMB affects two main groups of patients, who present with distinct demographic, clinical, and radiographic features. The first group consists primarily of older men with COPD. Such patients present with the classic form of NTMB infection, which may occur secondary to either MAC or M. kansasii. Clinical symptoms are often insidious and include cough, hemoptysis, and constitutional symptoms. The imaging features are almost identical to those of reactivation TB and are characterized by slowly progressive fibronodular opacities that are often associated with cavitation. The apical and posterior segments of the upper lobes and the superior segments of the lower lobes are most commonly involved.

The second group of patients is composed of elderly women with MAC infection. Such patients are immunocompetent and do not have a history of COPD. They typically present with chronic cough, but hemoptysis and constitutional symptoms are usually absent. The imaging features of MAC in this subgroup are best demonstrated by CT and include cylindrical bronchiectasis and multiple small (usually less than 5-mm-diameter) centrilobular nodules and/or tree-in-bud opacities. Foci of ground-glass opacification and consolidation may also be encountered. In contrast with the classic form of MAC infection, cavitation is uncommon in this subgroup. Although the distribution may be diffuse, the middle lobe and lingula are most commonly involved.

Because NTMB are common contaminants in the human environment, a diagnosis requires (1) evidence of cavitation or progressive changes on chest radiographs (classic form); (2) at least two positive sputum cultures; or (3) evidence of mycobacteria on biopsy or BAL. Precise identification of the infecting organism is important for directing appropriate therapy.

McGuinness G, Naidich DP, Garay SM, et al: Accessory cardiac bronchus: CT features and clinical significance. Radiology 189:563-566, 1993.

The CT image in this case demonstrates an anomalous blind-ending diverticulum (arrow) arising from the medial wall of the bronchus intermedius. This structure represents a cardiac bronchus, the only known true supernumerary anomalous bronchus. Other anomalies of the airway involve either a normal number of bronchi with ectopic locations (e.g., aberrant tracheal bronchus) or an absence of bronchi (e.g., bronchial atresia).

The cardiac bronchus always arises from the same location—the medial wall of the bronchus intermedius, above the origin of the superior segment bronchus. It is directed caudally toward the mediastinum. For this reason, it has been coined the cardiac bronchus.

Its length varies from a small, blind-ending pouch (such as in this case) to a longer branching structure. The longer configuration may be associated with rudimentary alveolar tissue in some cases. The cardiac bronchus is lined by endobronchial mucosa and contains cartilaginous rings within its walls.

This anomaly is usually incidentally discovered in asymptomatic patients. However, because a cardiac bronchus may serve as a reservoir for infectious material, affected patients may present with recurrent respiratory infections. Resultant inflammation and hypervascularity may also result in hemoptysis. Surgical excision is recommended for symptomatic patients.

Aberrant Right Subclavian Artery With Aortic Dissection

An aberrant right subclavian artery (ARSA) is the most common intrathoracic major arterial anomaly, with an incidence of approximately 1%. The ARSA arises as the last branch of the aortic arch and courses cephalad obliquely from left to right behind the trachea and esophagus. An aortic diverticulum, the diverticulum of Kommerell, may be present at the origin of this vessel.

In most patients, the anomaly is asymptomatic and discovered incidentally. A small minority of patients may develop difficulty in swallowing secondary to esophageal compression.

On chest radiography, you may observe the ARSA as an oblique opacity coursing superiorly from left to right, beginning at the level of the aortic arch. On barium swallow examinations, you may observe a characteristic oblique indentation on the posterior wall of the esophagus. An ARSA is easily identified on cross-sectional imaging studies such as the CT images in the figures. On such studies, the ARSA appears as a tubular structure arising from the aortic arch and coursing cephalad obliquely behind the trachea and esophagus. Aneurysmal dilation of the proximal portion of the ARSA is observed in approximately 10% of cases.

This case also demonstrates the presence of an aortic dissection. Note the presence of an intimal flap, which appears as a linear soft tissue density within the contrast-opacified vessels. Aortic dissection is characterized by a tear in the intima of the aortic wall, followed by separation of the tunica media. This process results in the creation of two channels for the passage of blood: a true and a false lumen.

Once you have identified an aortic dissection, it is important to determine its precise extent. Involvement of the ascending aorta (Stanford type A) requires surgical therapy. Extension of the dissection into the great vessels is an important preoperative finding. In contrast, isolated descending aortic dissections (Stanford type B) are generally managed medically.

Lee EY, Boiselle PM, Cleveland RH: Evaluation of congenital lung anomalies. Radiology 247:632-648, 2008.

The chest radiograph demonstrates a focal opacity in the posterior basal segment of the left lower lobe, which obscures a portion of the descending thoracic aortic interface and medial left hemidiaphragm. The CT image reveals a discrete soft tissue density mass that contains two tiny cystic foci. Note the presence of an adjacent tubular structure (arrow), which represents a systemic artery from the descending thoracic aorta. The imaging findings are consistent with a sequestration, which refers to an area of aberrant lung tissue that has no normal connection with the bronchial tree or pulmonary arteries and is supplied by a systemic artery.

Sequestrations are classified as either intralobar (contained within the substance of the lung) or extralobar (contained within its own pleural envelope). Intralobar sequestration is the most common type. Affected patients may be asymptomatic or may present with a history of recurrent pulmonary infections. The posterior basal segment is the most common location, and the left lung is affected twice as often as the right lung. Intralobar sequestrations may appear radiographically as a solid mass, a focal area of consolidation, or a cystic or multicystic lesion. The identification of a systemic arterial supply confirms the diagnosis. A systemic artery is usually visible on either contrast-enhanced CT or MRI. Failure to detect such a vessel does not exclude the diagnosis, however, and angiography may rarely be required for definitive diagnosis.

In contrast with intralobar sequestration, the extralobar variety usually presents during infancy. The typical radiographic appearance is a well-defined, solitary mass in close proximity to the posteromedial aspect of the hemidiaphragm. Less frequent sites of involvement include mediastinal and subdiaphragmatic locations. Approximately 90% of cases are in the left hemithorax. The arterial supply may arise from single or multiple systemic arteries. Extralobar sequestration is associated with systemic venous drainage, usually to the azygos system and less commonly into the portal vein, subclavian vein, or internal mammary vein.

Whereas extralobar sequestration is widely recognized as a congenital anomaly, there is emerging consensus that intralobar sequestration may be acquired secondary to chronic infection.

Acute Rejection Following Lung Transplantation

Erasmus JJ, McAdams HP, Tapson VF, et al: Radiologic issues in lung transplantation for end-stage pulmonary disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 169:69-78, 1997.

Lung transplantation is a potentially life-saving therapeutic option for certain patients with end-stage pulmonary disease. Because of the limited supply of donor lungs, single- rather than double-lung transplantation is usually performed. Single-lung transplantation is also technically easier to perform and has a slightly lower morbidity and mortality than double-lung transplantation. Most pulmonary disorders, including various causes of pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema, can be successfully managed with single-lung transplantation. Exceptions are disorders such as cystic fibrosis that are associated with chronically infected lungs. Such patients require double-lung transplantation. Recently, transplantation of lobes from living-related donors has also been performed in patients with cystic fibrosis.

Early pulmonary postoperative complications of lung transplantation include reperfusion edema, acute rejection, and infection. Reperfusion edema, also referred to as reimplantation response, is caused by increased capillary permeability and occurs in the vast majority of transplanted lungs. It has a characteristic time course, usually beginning in the first 24 hours, peaking between 1 and 5 days, and resolving within approximately 10 days following transplantation. Acute rejection is a common complication within the first 3 months following transplantation. The first episode usually occurs in the first 5 to 10 days following surgery. Note that reperfusion edema begins earlier and peaks before this time. Infection is the most common pulmonary complication following transplantation. The type of organism varies depending on the time interval from surgery. In the first month, bacterial infections are most common. After the first month, atypical infections such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) are most common.

Jeong YJ, Lee KS: Pulmonary tuberculosis: up-to-date imaging and management. AJR Am J Roentgenol 191:834-844, 2008.

Moon WK, Mim J, Yeon KM, Han MC: Tuberculosis of the central airways: CT findings of active and fibrotic disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 169:648-653, 1997.

Airway involvement has been reported in 10% to 20% of all patients with pulmonary TB. It may result from several mechanisms: (1) direct contact of the airway mucosa with infected secretions; (2) submucosal spread of infection through the lymphatics from infected lymph nodes or lung; and (3) direct invasion of the airway by adjacent lymph nodes.

There are two stages of tracheobronchial involvement by TB. The first stage is characterized by hyperplastic changes. During this stage, tubercles form in the submucosal layer and are accompanied by ulceration and necrosis of the airway wall. The affected airway walls appear irregularly thickened with variable degrees of luminal narrowing. Hilar and mediastinal lymph node enlargement are commonly observed and frequently demonstrate peripheral enhancement with central low attenuation. Cavitary lung lesions may occasionally be seen within the lobes drained by the affected bronchi.

In the first figure, note the presence of irregular thickening of the anterior and lateral wall of the trachea, with eccentric luminal narrowing. In the second figure, there is irregular, lobulated thickening of the anterior wall of the airway with polypoid intraluminal extension. The contiguity of the airway disease with adjacent mediastinal lymph nodes suggests that the airway involvement is due to direct invasion by tuberculous lymph nodes.

The second stage is characterized by fibrostenotic features. In this stage, the bronchi are typically smoothly narrowed. The fibrostenotic phase can be complicated by postobstructive collapse.

In a study of 41 patients with TB of the airway, patients with a hyperplastic stage of TB demonstrated irregular and thick-walled airways, a pattern frequently reversible with medical therapy. In contrast, patients with fibrotic disease generally demonstrated smooth narrowing of the airways and minimal wall thickening, a pattern not reversible with medical therapy.

Acute Interstitial Pneumonia (AIP)

Johkoh T, Müller NL, Taniguchi H, et al: Acute interstitial pneumonia: thin-section CT findings in 36 patients. Radiology 211:859-863, 1999.

AIP is a rapidly progressive form of lung injury that represents an idiopathic form of adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and diffuse alveolar damage (DAD). A diffuse interstitial pneumonia that was originally thought to represent a rapidly progressive form of UIP, AIP is now recognized as a separate clinicopathologic entity and occurs much less commonly than UIP.

The diffuse idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs) have distinct clinical manifestations, pathologic features, and imaging findings and were classified in 2001 by an international consensus statement issued by the ATS and the ERS that recognized seven distinct clinicopathologic entities: IPF (UIP), NSIP, COP, AIP, RB-ILD, DIP, and LIP. Diffuse parenchymal diseases due to known causes and associations such as drugs and connective tissue diseases are not considered idiopathic.

Pregnancy Complicated by Pulmonary Edema Secondary to Preeclampsia

Fidler JL, Patz EF, Ravin CE: Cardiopulmonary complications of pregnancy: radiographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 161:937-941, 1993.

Pregnancy is normally associated with a variety of cardiopulmonary physiologic changes. Maternal blood volume and cardiac output increase by approximately 45% by midpregnancy. These changes are associated with increased pulmonary vascularity and progressive left ventricular dilation and mild hypertrophy.

There are a variety of cardiopulmonary complications of pregnancy, including cardiogenic and noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, pulmonary thromboembolism, aspiration pneumonitis, and pneumonia. Other rare complications include metastatic disease from gestational trophoblastic neoplasm, pneumothorax, and pneumomediastinum.

The patient in this case developed preeclampsia during her third trimester of pregnancy that was complicated by pulmonary edema. Preeclampsia is characterized by the development of hypertension, proteinuria, and edema after 24 weeks’ gestation. Eclampsia refers to the development of seizures. In patients with preeclampsia, hypertension may become severe enough to produce acute cardiac failure. Radiographs typically show pulmonary edema with a variable heart size. In this patient, the pulmonary edema was asymmetric, reflecting gravitational dependency of pulmonary edema due to the patient’s preference for lying on her left side. Another cardiogenic cause of pulmonary edema is peripartum cardiomyopathy, which occurs in the last month of pregnancy or in the first 6 months following delivery. Radiographs demonstrate marked cardiac enlargement that may be accompanied by pulmonary edema.

Lipomatous Hypertrophy of the Interatrial Septum (LHIS)

Fan CM, Fischman AJ, Kewk BH, et al: Lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum: increased uptake on FDG PET. AJR Am J Roentgenol 184:339-342, 2005.

LHIS refers to the presence of a fat-attenuation interatrial mass. LHIS is usually incidentally detected on CT scans of asymptomatic patients. An association with atrial arrhythmias has been reported in some cases and is thought to occur secondary to disruption of septal conduction pathways.

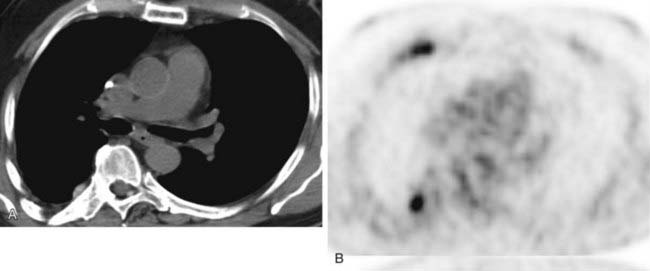

Pathologically, LHIS demonstrates multiloculated, granular lipocytes within the interatrial septum. In contrast to lipomas, the adipose tissue in LHIS is unencapsulated. The lipocytes in LHIS are the morphologic cells found in fetal or brown fat. Interestingly, LHIS may result in false-positive findings on PET scans due to preferential uptake of 2-[fluorine-18] fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) by brown fat, especially in the fasting state. Thus, when you see increased uptake within the right heart on FDG-PET studies, you should carefully correlate with CT findings for the presence of LHIS to avoid a false-positive diagnosis of cardiac malignancy.

The typical CT appearance is a nonenhancing, smoothly marginated, dumbbell-shaped, homogeneous, fat attenuation mass that is usually confined to the interatrial septum. The characteristic dumbbell shape is due to sparing of the fossa ovalis.

Remy-Jardin M, Pistolesi M, Goodman LR, et al: Management of suspected acute pulmonary embolism in the era of CT angiography: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology 245:315-329, 2007.

The MR angiogram demonstrates a normal appearance of the pulmonary vasculature of the right lung and complete absence of pulmonary vasculature within the left lung. Note the abrupt cut-off of the LPA due to an acute embolus.

A unilateral, completely obstructing embolus is an uncommon manifestation of acute pulmonary thromboembolism. In fact, when confronted with a nuclear medicine ventilation-perfusion scan that demonstrates a unilateral absence of perfusion, you should first consider nonthromboembolic causes such as mediastinal and hilar masses, ascending aortic aneurysm and dissection, pulmonary artery hypoplasia and agenesis, and pulmonary artery sarcoma and pneumonectomy. In this patient, the MRI examination revealed an obstructing, nonenhancing intrinsic filling defect in the LPA, consistent with an acute PE.

Several exciting recent technologic advances in MRI, including parallel imaging, view sharing, and time-resolved echo-shared angiography techniques, have resulted in an enhanced ability to evaluate for PE with MRI owing to shortened acquisition times, reduced motion artifacts, and improved spatial resolution.

According to the 2007 Fleischner Society statement regarding management of suspected acute PE, MR angiography of the pulmonary arteries and MR venography for deep vein thrombosis performed with state-of-the-art techniques can potentially serve as a second-line examination in the evaluation of suspected acute PE in patients who are unable to receive iodinated contrast material for CT or for whom ionizing radiation is of concern. Currently, CT angiography remains the study of choice for acute PE owing to its high accuracy, widespread access, rapid acquisition time, and superb ability to simultaneously assess the lungs for potential alternative diagnoses.

Alpha1-antitrypsin (AAT) Deficiency

Wood AM, Stockley RA: Alpha one antitrypsin deficiency: from gene to treatment. Respiration 74:481-492, 2007.

The CT image demonstrates diffuse panlobular emphysema in the lower lung zones. The upper lobes (not shown) were relatively spared of this process. Panlobular emphysema is characterized by fewer and smaller-than-normal pulmonary vessels. This appearance has been described as a simplification of normal lung architecture. AAT deficiency, the diagnosis in this case, is characterized by a basilar distribution of panlobular emphysema.

AAT deficiency, also referred to as alpha1-protease inhibitor deficiency, is an inherited disorder that is characterized by abnormally low levels of alpha1-protease inhibitor. This protein inhibits a number of lysosomal proteases and prevents the damaging effects of elastases released by macrophages and neutrophils. Because the administration of elastase has been shown to produce emphysema in animal models, it is not surprising that patients with reduced levels of protease inhibitors are at risk for developing this complication. Patients who are homozygous for this disorder have a very low level (approximately 20% of normal) of alpha1-protease inhibitor and are at high risk for developing emphysema. This risk is increased by cigarette smoking.

Interestingly, patients with AAT deficiency have a high prevalence of bronchiectasis, which has been reported in approximately 40% of cases. In the figure, note the presence of bronchial wall thickening and dilation, which is most pronounced in the right lower lobe. The mechanism by which bronchiectasis develops in these patients is uncertain. It has been hypothesized that destruction of elastic fibers in the walls of bronchi and bronchioles plays an important role in this process.

Treatment approaches targeting the molecular basis of this disease are currently under investigation and include AAT replacement, gene therapy, and stem cells.

Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia

Mueller-Mang C, Grosse C, Schmid K, et al: What every radiologist should know about idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Radiographics 27:595-615, 2007.

Organizing pneumonia is characterized pathologically by the presence of granulation tissue polyps within the alveolar ducts and alveoli. Although it may be idiopathic, organizing pneumonia has been described in association with a number of entities, including pulmonary infection, drug reactions, collagen-vascular disorders, and vasculitides. Thus, the diagnosis of COP requires the exclusion of known underlying causes.

Affected patients typically present clinically with a nonproductive cough. Associated symptoms may include dyspnea, malaise, and low-grade fever. The majority of cases respond to steroids and have a favorable prognosis. However, some patients relapse following cessation of therapy. Interestingly, lung parenchymal opacities associated with COP may migrate, even in the absence of treatment.

Radiographic findings consist primarily of patchy, nonsegmental, unilateral or bilateral foci of consolidation. The characteristic peripheral distribution of consolidation associated with COP may not be readily apparent on chest radiographs and is seen more frequently on CT scans.

Characteristic HRCT imaging features include patchy bilateral airspace consolidation with a peripheral or peribronchovascular distribution. In some cases, the extreme subpleural region of the lung is spared. The opacities may vary from ground glass to consolidation. In some cases, the periphery may appear more dense than the center, an appearance referred to as the reverse halo or atoll sign. Poorly defined lung nodules may also be observed and are often peribronchiolar in distribution. Thus, the presence of peripheral and peribronchovascular consolidation with associated small lung nodules in this case is most suggestive of COP.

Dialani V, Ernst A, Sun M, et al: MDCT detection of airway stent complications: comparison with bronchoscopy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 191:1576-1580, 2008.

The axial CT image in the first figure and the two-dimensional sagittal reformatted image in the second figure demonstrate the presence of a tracheal stent within the lower cervical portion of the trachea. Note the presence of focal stent fracture and disruption posteriorly (arrows). This patient underwent stent placement for tracheal stenosis. She subsequently presented with evidence of wire fragments in her sputum, prompting this CT examination.

Airway stents are increasingly employed in the treatment of a variety of airway abnormalities. There are two major types: metallic and silicone. Once placed into the airway, metallic stents become incorporated into the bronchial wall or epithelialized, limiting potential migration and permitting ciliary activity to continue. Metallic stents are difficult to remove once employed and have a greater complication rate than silicone stents. For this reason, their use should be limited to palliative treatment of patients with inoperable airway involvement by malignancy. Patients with airway compromise due to benign causes should be treated with silicone stents.

Prior to the advent of airway stenting, the treatment of tracheal stenosis was limited to surgical therapy. Surgical treatment of tracheal abnormalities with end-to-end reanastomosis is possible only when there is sufficient length of the airway. Stenting is not limited by this factor and thus provides an additional therapeutic option for many patients who are not surgical candidates.

Prior to stent placement, CT accurately depicts the number and length of airway stenoses. Following placement of a stent, CT is an ideal modality for assessing for complications such as stent migration, stent fracture, and intraluminal narrowing. Recently, MDCT has been shown to be highly accurate for detecting stent complications, with similar accuracy to the reference standard of bronchoscopy.

Jeung MY, Gasser B, Gangi A, et al: Imaging of cystic masses of the mediastinum. Radiographics 22:S79-S93, 2002.

Thymic cysts are an uncommon cause of an anterior mediastinal mass. They may be congenital or acquired. Congenital cysts are probably derived from remnants of the fetal thymopharyngeal duct. Acquired cysts may develop following radiation therapy for Hodgkin’s disease. Less commonly, they may occur following thoracotomy or after chemotherapy for a malignant neoplasm. An association with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection has also been reported.

On imaging studies, a thymic cyst typically appears as a well-defined, cystic mass with an imperceptible wall. In a minority of cases, curvilinear calcifications may be identified within the wall of thymic cysts. On CT, thymic cysts typically demonstrate fluid attenuation. On MRI, thymic cysts usually demonstrate low signal intensity on T1W images and increased signal intensity on T2W images. However, the appearance may vary if the cyst has been complicated by hemorrhage or infection. The imaging features in this case are typical of an uncomplicated thymic cyst. Incidentally noted are numerous calcified pleural plaques, consistent with prior asbestos exposure.

When you identify an anterior mediastinal mass with solid and cystic components, you should consider the possibility of a solid anterior mediastinal mass that has undergone cystic necrosis. For example, thymoma and Hodgkin’s lymphoma may contain cystic areas, occasionally associated with a relatively small amount of neoplastic tissue. Germ cell neoplasms such as mature teratomas frequently contain cystic components intermixed with solid elements. The identification of cystic elements in conjunction with fat and/or calcium should suggest this diagnosis.

Ghaye B, Szapiro D, Fanchamps JM, Dondelinger RF: Congenital bronchial abnormalities revisited. Radiographics 21:105-119, 2001.

The tomogram demonstrates an anomalous bronchus arising from the right lateral wall of the trachea, proximal to the origin of the right mainstem bronchus. The term tracheal bronchus has been used to describe this congenital bronchial anomaly, which may supply the apical segment of the right upper lobe or the entire right upper lobe. The latter configuration is also referred to as a pig bronchus.

Affected patients are usually asymptomatic. In a minority of cases, the bronchial orifice is narrow, which may lead to recurrent pneumonias and bronchiectasis. Following intubation, the aberrant bronchus may become occluded by the endotracheal tube balloon cuff, resulting in atelectasis within the corresponding segment or lobe that is supplied by the aberrant bronchus.

Rossi SE, Erasmus JJ, McAdams HP, et al: Pulmonary drug toxicity: radiologic and pathologic manifestations. Radiographics 20:1245-1259, 2000.

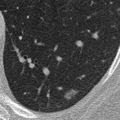

The noncontrast CT images presented in this case demonstrate several small pulmonary nodules with a subpleural distribution. Note the high attenuation of these lesions, a finding that is characteristic of lung toxicity due to amiodarone, a triiodinated compound that is used to treat cardiac arrhythmias. Pulmonary toxicity occurs in 5% to 20% of patients treated with amiodarone and is dose related.

There are three distinct clinical presentations of amiodarone toxicity. The most common presentation is a subacute onset of dyspnea, nonproductive cough, and weight loss. Radiographs typically reveal a diffuse linear pattern that may be difficult to distinguish from congestive heart failure. This usually correlates pathologically with an NSIP pattern. A less common presentation (observed in approximately one third of patients) is characterized by an acute onset of symptoms that mimic an infectious pneumonitis. Radiographs of these patients typically demonstrate patchy alveolar opacities with a peripheral distribution that correlate pathologically with COP. Unenhanced CT scans in these patients typically reveal high-attenuation foci of parenchymal opacification, with attenuation values ranging from approximately 80 to 175 Hounsfield units. This appearance reflects the high concentration of amiodarone, a triiodinated agent, within these regions of lung parenchyma. A third rare but potentially fatal form of pulmonary toxicity is ARDS.

Note the high attenuation of the liver in the second figure, a common finding in patients treated with amiodarone. Thus, the combination of high-attenuation focal parenchymal opacities and a high-attenuation liver is highly suggestive of amiodarone pulmonary toxicity. Prompt recognition is important, because amiodarone pulmonary toxicity is frequently reversible after withdrawal of the drug. Although clinical symptoms usually resolve within 2 to 4 weeks of drug withdrawal, chest radiographic abnormalities typically clear more slowly, in approximately 3 months.

Koyama T, Ueda H, Togashi K, et al: Radiologic manifestations of sarcoidosis in various organs. Radiographics 24:87-104, 2004.

CT demonstrates numerous small nodules, located predominantly in an axial distribution, coursing along the bronchovascular bundles. This distribution of nodules is associated with a relatively limited differential diagnosis, including sarcoidosis, lymphangitic carcinomatosis, lymphoma, and Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Sarcoid nodules, which represent noncaseating granulomas, are typically perilymphatic in distribution. Such nodules are predominantly located along the bronchovascular bundles, radiating from the hila in an axial distribution. Less frequently, the nodules are located in the interlobular septa and subpleural lymphatics, both peripherally and along interlobar fissures. Note that several of the nodules in this patient are located peripherally and adjacent to pleural surfaces.

A recent study demonstrated that CT images of patients with sarcoidosis frequently reveal evidence of small airways disease such as a mosaic pattern of lung attenuation and air trapping on expiratory images. It has been postulated that small airways disease in sarcoid may arise from one of two possible mechanisms: intrinsic granulomas within the small airways or extrinsic peribronchiolar fibrosis.

The combination of airways involvement and interstitial involvement in patients with sarcoidosis may result in heterogeneous patterns of functional impairment on pulmonary function tests. Patients with sarcoidosis may demonstrate a variety of pulmonary function test abnormalities, including restrictive, obstructive, and combined restrictive and obstructive patterns.

Saphenous Vein Graft Aneurysm Following CABG Surgery

Nishimura K, Nakamura Y, Harada S, et al: Saphenous vein graft aneurysm after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 15:61-63, 2009.

The chest radiograph shown in the first and second figures demonstrates a well-circumscribed anterior mediastinal mass located to the left of midline, in close proximity to surgical sutures related to the CABG procedure. The presence of an anterior mediastinal mass in a patient who has undergone CABG should raise the suspicion of an aneurysmal venous graft. The diagnosis can be confirmed with contrast-enhanced CT or MRI. The contrast-enhanced CT image in the third figure confirms the diagnosis of an aneurysm that contains a large amount of peripheral thrombus.

Aneurysms of saphenous vein grafts are a rare but serious complication of CABG and are typically detected 10 to 20 years after the surgery. False aneurysms, which are characterized by a disrupted vessel wall, are more common than true aneurysms, which are characterized by an intact vessel wall. False aneurysms are most commonly located at the anastomotic sites. Such aneurysms have been described in association with wound infection, intrinsic weakness of the graft wall, and iatrogenic trauma to the vein during harvesting. In contrast, true aneurysms are identified most commonly within the body of the graft. True aneurysms are thought to arise owing to progressive atherosclerosis related to exposure of saphenous vein grafts to systemic blood pressure.

Venous graft aneurysms are often asymptomatic and discovered as an incidental finding on routine chest radiographs. When symptomatic, patients generally present with symptoms of myocardial ischemia. Complications of venous graft aneurysms include myocardial infarction, distal embolization, fistula formation to the right atrium or right ventricle, and rupture and secondary hemorrhage. Treatment includes resection of the aneurysm and myocardial revascularization. Catheter-based coil embolization may be considered in high-risk surgical patients.

Infectious Small Airways Disease in Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

Aviram G, Fishman JE, Boiselle PM: Thoracic infections in human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Semin Roentgenol 42:23-36, 2007.

The HRCT images reveal numerous small, branching and nodular centrilobular opacities, consistent with bronchiolitis. There is also mild bronchial dilation and bronchial wall thickening. The findings are consistent with infectious airways disease. In recent years, infectious bronchiolitis and bronchitis have been increasingly recognized in HIV-positive patients. Interestingly, HIV-positive patients also have an increased prevalence of bronchiectasis.

Chest radiograph findings may include bronchial wall thickening and scattered small nodular opacities, the latter representing impacted bronchioles. A symmetric lower lobe predominance is often observed. Isolated small airways disease may be quite difficult to diagnose by conventional radiography because findings are often subtle and may mimic an interstitial pattern. The HRCT features of small airways disease are characteristic and include small (2- to 4-mm) centrilobular branching opacities and nodules, which represent bronchioles impacted with inflammatory secretions. The branching opacities represent bronchioles in profile (oriented in the plane of the transverse CT image), whereas the nodules represent bronchioles in cross section (oriented perpendicular to the image). The term tree-in-bud has been used to describe this characteristic appearance. In an HIV-positive patient, this pattern is most closely associated with a variety of infectious organisms, but it is only rarely associated with Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia.

CMV Pneumonia in an Organ Transplant Recipient

Poghosyan T, Ackerman SJ, Ravenel JG: Infectious complications of solid organ transplantation. Semin Roentgenol 42:11-22, 2007.

Following renal transplantation, patients are at risk for a variety of infections due to the effects of immunosuppressive therapy. A knowledge of the interval between transplantation and the development of pulmonary infections can help you predict the types of organisms that are likely to cause pulmonary infections.

During the first month following transplantation, the immunosuppressive agents have not yet had a profound effect on the patient’s immune system. Opportunistic infections are unusual during this period. Infections are usually caused by organisms that are typically encountered in patients with normal immunity after surgery, particularly gram-negative organisms, and commonly occur owing to aspiration or wound catheter-related infections.

Immunosuppression is usually most severe during the second to sixth months following renal transplantation. T-cell–mediated immunity is most severely depressed, placing patients at highest risk for viral and fungal infections. CMV is the most common viral agent to affect these patients, but prophylactic preventive strategies have markedly reduced the prevalence of CMV infection in the posttransplant setting. Radiographs may show a reticular or nodular pattern and, less commonly, consolidation and discrete lung nodules and masses.

After the sixth month, the immunosuppression regimen is gradually tapered. As the patient’s immune system recovers, the organisms that most commonly produce pneumonia in this period are those responsible for most community-acquired pneumonias, such as S. pneumoniae. Because immunosuppressive agents are tapered but not discontinued, patients continue to remain at risk for opportunistic infections, particularly fungal organisms.

Pulmonary Venoocclusive Disease

Resten A, Maitre S, Humbert M, et al: Pulmonary hypertension: CT of the chest in pulmonary venoocclusive disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 183:65-70, 2004.