Cesarean Section Hysterectomy

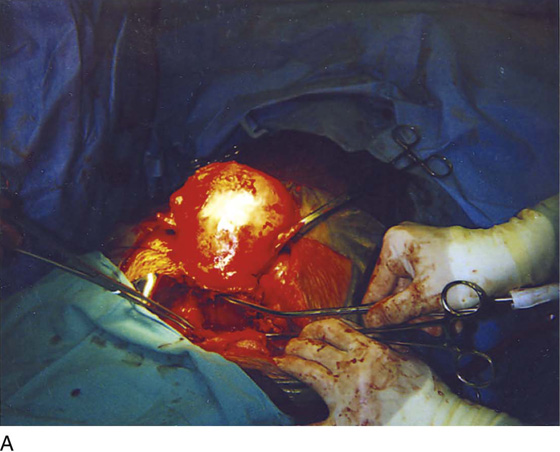

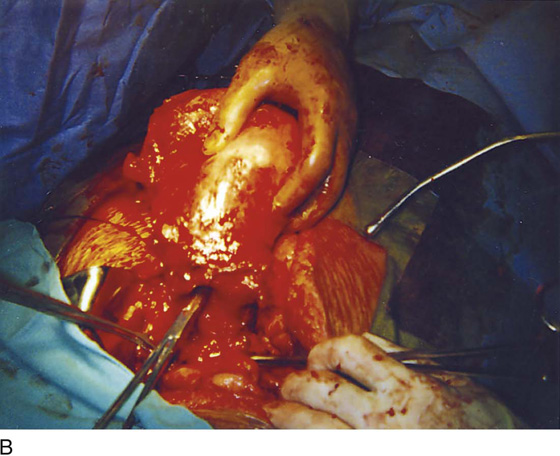

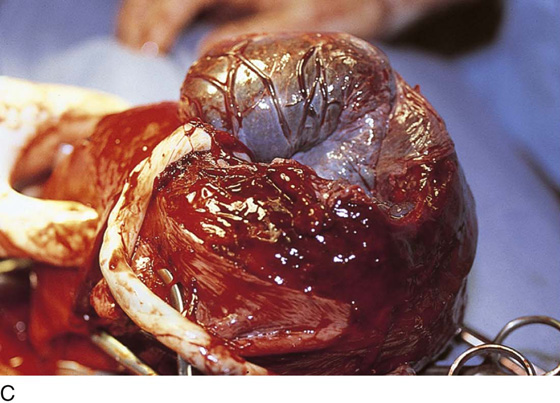

The distinguishing features of an abdominal hysterectomy performed on a pregnant patient, whether associated with cesarean section or performed after a vaginal delivery, are (1) the greater vascularity compared with the nonpregnant patient, (2) the close association of a dilated cervix and vagina with the greatly distended ureters, and (3) a tendency for the postpartum patient to form blood clots. Most hysterectomies in this setting are performed as an emergency operation, typically to treat bleeding difficulties (Figs. 19–1A–C).

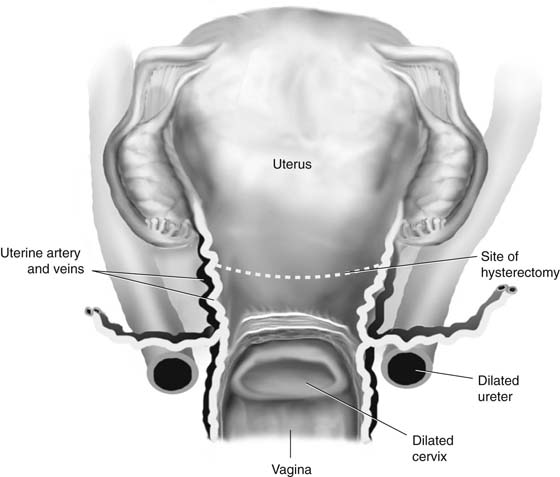

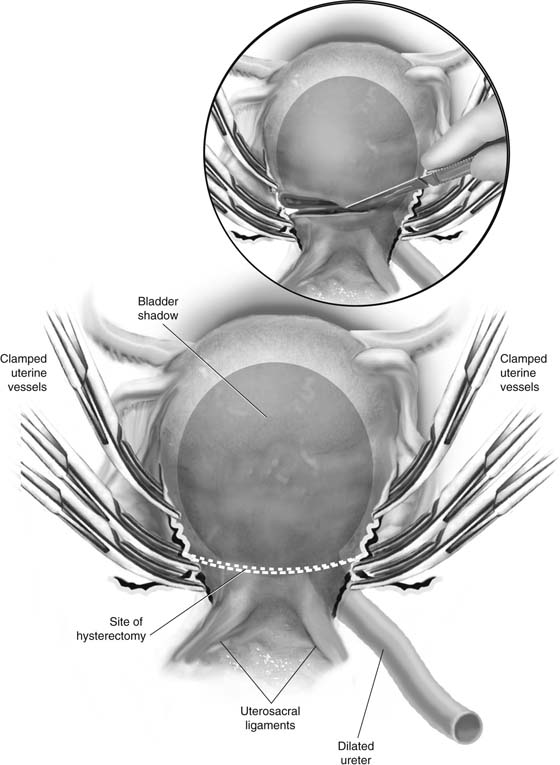

The ureters must be identified on the right and left sides of the pelvis. They are best located as they cross the common iliac vessels and descend into the pelvis. The best operation to perform under these circumstances is a subtotal hysterectomy (Fig. 19–2). The cervix can be removed months or years later, via the vaginal or the abdominal route, if necessary. The subtotal hysterectomy is least likely to result in ureteral injury and is completed most rapidly.

First, if a cesarean section has been performed, the uterus is closed with a running lock stitch of 0 Vicryl. Next, the round ligaments are clamped, sutured, and cut close to the uterus. Then, if the ovaries are to be retained, the utero-ovarian ligaments and oviducts are triply clamped, cut, and suture-ligated with 0 Vicryl.

The ureters must be dissected and traced under direct vision inferiorly to the level of the uterine arteries.

The bladder peritoneum has already been pushed inferiorly as part of the cesarean section. The uterine vessels are skeletonized. Three clamps (Zeppelin) are placed on the uterine arteries at the cervicouterine junction and above the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments (Fig. 19–3). The fundus is then sharply cut away from the cervix (see Fig. 19–3, Inset). The cervical stump is closed with figure-of-8 sutures using 0 Vicryl. The uterine vessels are doubly secured with 0 Vicryl transfixing sutures. The peritoneum is closed with a running 3-0 Vicryl continuous suture. No suspension is required because the major supporting ligaments have been left intact (Fig. 19–4).

FIGURE 19–1 A. This uterus ruptured at the site of a previous transverse cesarean section scar. B. Enlarged view of the lower segment rupture. Note that the Kelly clamp points to the site of the rupture. C. The uterus has been opened somewhat irregularly because of a rupture. The placenta is being delivered before hysterectomy is performed.

FIGURE 19–2 Anterior view of the uterus. Note the positions of the greatly dilated ureters and their close proximity to the dilated cervix. A trace has been placed indicating the site for subtotal hysterectomy.

FIGURE 19–3 Posterior view of the uterus. The uterine arteries have been doubly clamped, and the third clamp is placed on the uterine vessels higher up to control back-bleeding. Inset, A scalpel cuts the uterus, separating the corpus from the cervix. The line of incision is between the upper clamp and the lower two clamps.

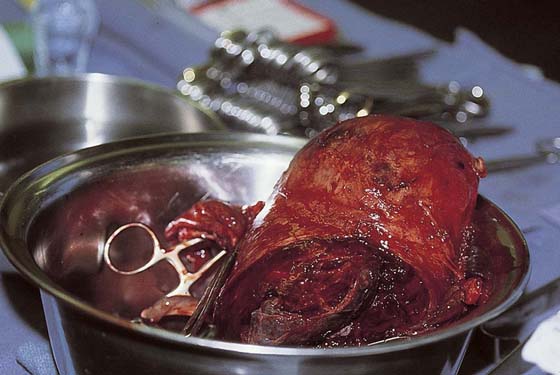

FIGURE 19–4 The operation is quickly completed and the specimen is removed from the operative field.