CHAPTER 11 Cervical plexus block

Clinical anatomy

The branches of the superficial cervical plexus supply the skin and superficial structures of the head, neck, and shoulder. There are four cutaneous branches, which become subcutaneous at the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Fig. 11.1). The lesser occipital and great auricular are derived from the C2 and C3 roots and run in a cephalad direction. The lesser occipital nerve supplies sensation to the upper side of the neck, the upper part of the auricle, and the adjoining skin of the scalp. The great auricular nerve is the largest cutaneous branch and divides into an anterior and a posterior branch. The posterior branch supplies the skin lying behind the ear and the medial and lateral surfaces of the lower part of the auricle. The anterior branch supplies the skin in the lower posterior part of the face and the concave surface of the auricle. The transverse cervical nerve, also from C2 and C3 roots, runs horizontally across the neck and provides sensory innervation to the anterolateral aspect of the neck from the mandible to the sternum. The supraclavicular branch, from the C3 and C4 roots, runs caudally over the clavicle and divides into three branches: medial, intermediate, and lateral. It provides sensory innervation to the lower aspect of the neck, acromial region of the neck, and as far as the second intercostal space on the chest.

Surface anatomy

The main landmarks for the superficial cervical plexus block (Fig. 11.2) include the mastoid process, suprasternal notch, and posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle at the level of the cricoid cartilage. The sternocleidomastoid muscle and its posterior border can be accentuated by asking the patient to perform a head lift. The external jugular vein crosses the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle close to the injection site. It can be accentuated by asking the patient to perform a Valsalva maneuver. The carotid artery can be palpated medial to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and indicates the vascular nature of the territory.

The main landmarks for the deep cervical plexus block (Fig. 11.3) include the mastoid process; the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle at the level of the cricoid cartilage; C6 transverse process (the most prominent cervical transverse process); and the thyroid cartilage.

Sonoanatomy

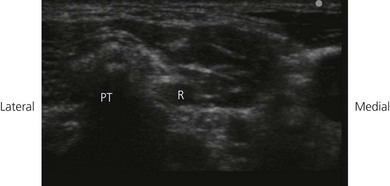

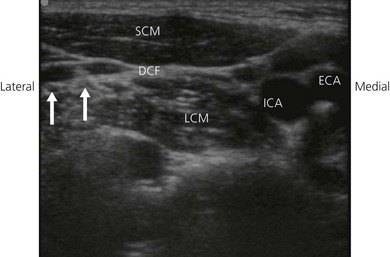

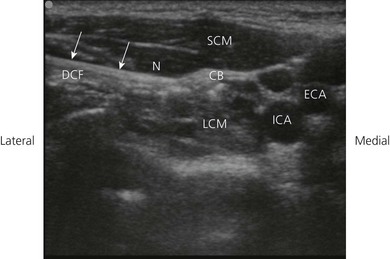

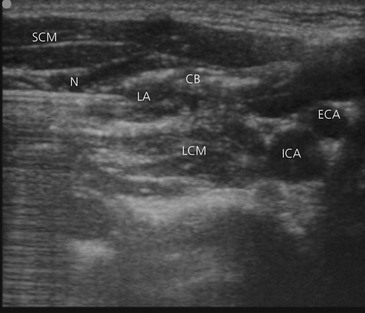

The cervical plexus is found at the level of the first four cervical vertebrae deep to the sternocleidomastoid, in the layer superficial to the scalenus medius and levator scapulae. The cervical plexus can be further divided into a superficial and deep portion. The superficial branches perforate the cervical fascia to supply skin and other integumental structures whilst the deep branches predominantly supply muscle. The patient is positioned supine with the head slightly turned to the opposite side. Perform a systematic survey from superficial to deep, medial to lateral and cranially. A high frequency ultrasound transducer is placed in a coronal plane anterolateral to the neck to identify the respective vertebral level The transverse process of C7 usually does not have an anterior tubercle, but only one prominent posterior tubercle (Fig 11.4). Additionally, the C6 transverse process is sonographically verified by tracing the course of the vertebral artery, which usually enters the foramen at that vertebra. After achieving a coronal echoplane with the depiction of the transverse processes of C6 and C7, the transducer is shifted cranially and the fourth cervical vertebra (C4) is identified by counting the respective vertebral levels upwards. Parts of the superficial plexus can be identified in the double fascial layer in all patients at the level of C4. This double fascial layer is formed by the fascia of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the deep cervical fascia (Fig. 11.5). Here the C4 nerve root can also be seen arising between the anterior and posterior tubercles of the fourth transverse process (Fig. 11.5). This level correlates with the carotid bifurcation in most patients (Fig. 11.5).

Technique

Landmark based approach

Superficial cervical plexus

The patient is placed in the supine position, with the head facing away from the side to be blocked. The mastoid process and suprasternal notch are identified and marked. The next step is to identify the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle between these two landmarks. The needle insertion site is marked at the midpoint of the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid adjacent to the cricoid cartilage (Fig. 11.2).

The needle insertion site is infiltrated with local anesthetic using a 25-G needle. A 23-G needle is then inserted in a perpendicular fashion just behind the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Fig. 11.6). A ‘pop’ is often felt as the cervical fascia is penetrated. Incremental injection of local anesthetic (5 mL) is made with repeated aspiration. This is the preferred block site due to the tight arrangement of the plexus here. Local anesthetic injection should form a contour corresponding to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The needle is then redirected both superiorly and inferiorly along the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid while making subcutaneous injections (5-mL injections are made in each direction).

Deep cervical plexus

The mastoid process and transverse process of C6 are identified and marked with a pen (Fig. 11.3). A line is drawn connecting these two points. A second line is drawn parallel and 1 cm posterior to the first line (Fig. 11.3). The transverse process of the fourth cervical vertebrae can be located, having previously located the transverse process of the sixth cervical vertebrae in relation to the cricoid cartilage. The transverse process of the fourth cervical vertebrae can also be located by drawing a horizontal line from the superior aspect of the thyroid cartilage. Although a single-injection technique at C4 can be used, block at C3 is also possible. C3 can be located 1.5 cm cephalad from C4.

Needle (23-G) orientation is perpendicular to the skin and slightly caudad (Fig. 11.7) until bony contact at 1–2 cm from the skin. A paresthesia in the distribution of the cervical plexus may be found. At this point the needle is gently withdrawn 1 mm and incremental injections of local anesthetic (3–5 mL) are made with repeated aspiration. The fingers of the palpating hand should be used to fix the skin at the transverse process of the level to be blocked. This decreases the depth of the needle insertion and makes the block both easier and safer to perform.

Ultrasound-guided approach

Intravenous access, electrocardiogram (ECG), pulse oximetry and blood pressure monitoring are established. Maximized comfort for the operator and patient is an important step in pre-procedure preparation. For the ultrasound-guided cervical plexus block, the patient is placed in the supine position, with the head turned slightly to the side opposite that to be blocked. The operator stands or sits adjacent to the side to be blocked. The ultrasound screen, transducer, needle, and plane of imaging should all be placed in one view for the operator. For the cervical plexus block, the ultrasound screen is placed above the shoulder on the side to be blocked (Fig 11.8). Room lights may be turned down to enhance image viewing. The operating lights can be used to maintain some working lighting in the background. The patient is asked to raise their head to identify the interscalene groove.

Developing and maintaining a predetermined basic scanning routine is of enormous help in improving operator confidence and success. A transverse image of the superficial cervical plexus is obtained (Fig. 11.5). The superficial cervical plexus is kept in the center of the field of view. The needle entry site is at the lateral-most end of the linear transducer. A free hand technique, rather than the use of a needle guide, is preferred. A 21-GA × 50-mm needle (B.Braun, Bethlehem PA) is inserted parallel to the axis of the beam of the ultrasound transducer with the bevel facing the transducer (Fig 11.9). The needle is attached to sterile extension tubing, which is connected to a 10-mL syringe and flushed with local anesthetic solution to remove all air from the system. It is then introduced at the lateral-most end of the transducer and visualized along its entire path to the superficial cervical plexus (Fig 11.10). It is important not to advance the needle without good visualization. This may require needle or ultrasound transducer adjustment.

Once the needle has approached the superficial cervical plexus, 1–2 mL of local anesthetic may be injected to confirm correct needle placement. Local anesthetic appears as a hypoechoic image. Correct needle placement is confirmed by observing solution surrounding the superficial cervical plexus (Fig 11.11). For a superficial cervical plexus block, local anesthetic should be injected between the double layer of the fascia rather than deep to it. Penetrating the fascia will lead to a deep cervical plexus block rather than a superficial cervical plexus block. Local anesthetic injected deep to the fascia does not consistently reach all relevant superficial parts of the cervical plexus. Following confirmation of correct needle placement, 10 mL of local anesthetic solution can be injected to achieve blockade.

Adverse effects

Clinical pearls

Merle JC, Mazoit JX, Desgranges P, et al. A comparison of two techniques for cervical plexus blockade: evaluation of efficacy and systemic toxicity. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:1366-1370.

Stoneham MD, Knighton JD. Regional anaesthesia for carotid endarterectomy. Br J Anaesth. 1999;82:910-919.

Sandeman DJ, Griffiths MJ, Lennox AF. Ultrasound guided deep cervical plexus block. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2006;34(2):240-244.

Roessel T, Wiessner D, Heller AR, et al. High-resolution ultrasound-guided high interscalene plexus block for carotid endarterectomy. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32(3):247-253.

Soeding P, Eizenberg N. Review article: anatomical considerations for ultrasound guidance for regional anesthesia of the neck and upper limb. Can J Anesth. 2009;56:518-533.

Martinoli C, Bianchi S, Santacroce E, et al. Brachial plexus sonography: a technique for assessing the root level. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:699-702.

Pandit JJ, Satya-Krishna R, Gration P. Superficial or deep cervical plexus block for carotid endarterectomy: a systematic review of complications. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:159-169.