Chapter 38 Cervical Dysplasia and Cancer

Etiology and Epidemiology

Etiology and Epidemiology

Cervical cancer and its precursors have been associated with several epidemiologic variables (Box 38-1). These risk factors basically increase the likelihood of exposure to a high-risk HPV type.

The disease is relatively rare before 20 years of age, and the mean age is about 47 years.

Cervical Topography

Cervical Topography

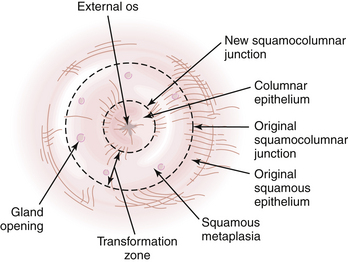

Throughout life, but particularly during adolescence and a woman’s first pregnancy, metaplastic squamous epithelium covers the columnar epithelium so that a new squamocolumnar junction is formed more proximally. This junction moves progressively closer to the external os and then up the endocervical canal. The transformation zone is the area of metaplastic squamous epithelium located between the original squamocolumnar junction and the new squamocolumnar junction (Figure 38-1).

Classification of an Abnormal Papanicolaou Smear

Classification of an Abnormal Papanicolaou Smear

In 1988, a consensus meeting was convened by the Division of Cancer Control of the National Cancer Institute to review existing terminology and to recommend effective methods of cytologic reporting. As a result of this meeting, the Bethesda system was devised and requires (1) a statement regarding the adequacy of the specimen for diagnosis, (2) a diagnostic categorization (normal or other), and (3) a descriptive diagnosis. A revised Bethesda system was developed in 2001 and is shown in Box 38-2.

BOX 38-2 Bethesda Classification of Cytologic Abnormalities (2001, Abridged)

Epithelial Cell Abnormalities

Squamous Cell

CERVICAL INTRAEPITHELIAL NEOPLASIA

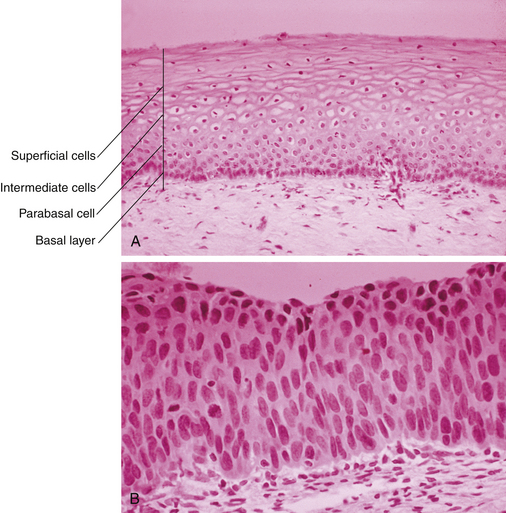

CIN represents a spectrum of disease, ranging from CIN I (mild dysplasia) to CIN III (severe dysplasia and carcinoma in situ). At least 35% of patients with CIN III develop invasive cancer within 10 years, whereas lower grades of CIN often spontaneously regress. With CIN, there is abnormal epithelial proliferation and maturation above the basement membrane. Involvement of the inner one third of the epithelium represents CIN I, involvement of the inner one half to two thirds represents CIN II, and full-thickness involvement represents CIN III (Figure 38-2). The disease is asymptomatic.

Evaluation of a Patient with an Abnormal Papanicolaou Smear

Evaluation of a Patient with an Abnormal Papanicolaou Smear

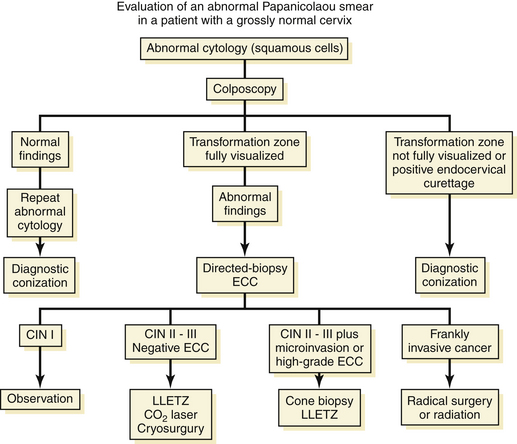

An algorithm for the evaluation of patients with abnormal Pap smears is presented in Figure 38-3.

Treatment of Intraepithelial Neoplasia

Treatment of Intraepithelial Neoplasia

Invasive Cancer

Invasive Cancer

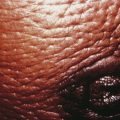

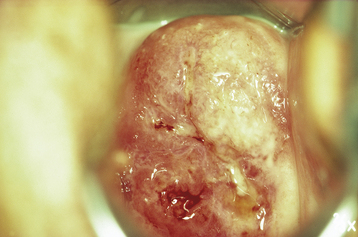

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

On pelvic examination, the cervix may be ulcerative or exophytic (Figure 38-4). It usually bleeds on palpation, and there is often an associated serous, purulent, or bloody discharge. The lesion may involve the adjacent vagina and extend toward the introitus.

PATTERNS OF SPREAD

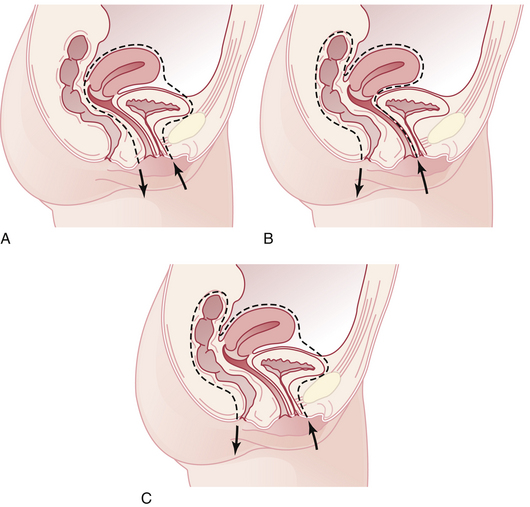

Invasive cervical cancer spreads by direct invasion of cervical stroma, corpus, vagina, and parametrium; lymphatic spread to pelvic and then para-aortic lymph nodes (Figure 38-5); and hematogenous spread, particularly to the lungs, liver, and bone.

PREOPERATIVE INVESTIGATIONS

The official International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging for cervical cancer is a clinical staging method based on physical examination and noninvasive testing (Table 38-1). Studies allowed include biopsies, cystoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, chest and skeletal radiographs, intravenous pyelography, and liver function tests. Lung metastases are seen in about 5% of patients with advanced disease and almost never in early disease.

TABLE 38-1 INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF GYNECOLOGY AND OBSTETRICS (FIGO) STAGING OF CERVICAL CARCINOMA

| PREINVASIVE CARCINOMA | |

| Stage 0 | Carcinoma in situ, intraepithelial carcinoma (cases of stage 0 should not be included in any therapeutic statistics) |

| INVASIVE CARCINOMA | |

| Stage I | The carcinoma is strictly confined to the cervix. |

| Stage Ia | Invasive cancer is identified only microscopically. All gross lesions even with superficial invasion are Ib cancers. Invasion is limited to a measured stromal invasion, with a maximal depth of 5 mm and a horizontal extension of not more than 7 mm. |

| Stage Ia1 | Measured invasion of stroma not greater than 3 mm in depth and 7 mm in width |

| Stage Ia2 | Measured invasion of stroma greater than 3 mm and not greater than 5 mm and width not greater than 7 mm |

| Stage Ib | Clinical lesions confined to the cervix or preclinical lesions greater than stage Ia |

| Stage Ib1 | Clinical lesions not greater than 4 cm in size |

| Stage Ib2 | Clinical lesions greater than 4 cm in size |

| Stage II | The carcinoma extends beyond the cervix but has not extended to the pelvic wall or to the lower third of the vagina. |

| Stage IIa | No obvious parametrial involvement |

| Stage IIb | Obvious parametrial involvement |

| Stage III | The carcinoma has extended to the pelvic wall. On rectal examination, there is no cancer-free space between the tumor and the pelvic wall. The tumor involves the lower third of the vagina. All cases with hydronephrosis or nonfunctioning kidney should be included, unless they are known to be due to another cause. |

| Stage IIIa | Tumor involves lower third of the vagina with no extension to the pelvic wall. |

| Stage IIIb | Extension onto the pelvic wall and/or hydronephrosis or nonfunctioning kidney |

| Stage IV | The carcinoma has extended beyond the true pelvis or has clinically involved the mucosa of the bladder or rectum. A bullous edema, as such, does not permit a case to be allotted to stage IV. |

| Stage IVa | Spread of the growth to adjacent organs |

| Stage IVb | Spread to distant organs |

TREATMENT

Recurrent or Metastatic Disease

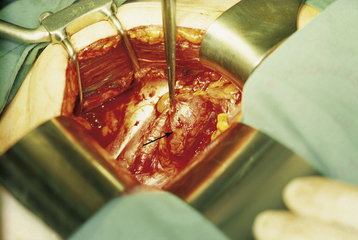

PELVIC EXENTERATION

Pelvic exenteration is generally reserved for patients who have a central recurrence following pelvic irradiation. Total exenteration involves removal of the pelvic viscera, including the uterus, tubes, vagina, ovaries, bladder, and rectum (Figure 38-6). Depending on the site and extent of the disease, the operation may be limited to an anterior exenteration, which spares the rectum, or a posterior exenteration, which spares the bladder.

Prognosis for Cervical Cancer

Prognosis for Cervical Cancer

Prognosis is related directly to clinical stage (Table 38-2).With more advanced stage of disease, the frequency of nodal metastasis escalates, and the 5-year survival rate diminishes. Adenocarcinomas and adenosquamous carcinomas have a somewhat lower 5-year survival rate than do squamous carcinomas, stage for stage.

| Stage | No. of Patients | Five-Year Survival (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ia1 | 860 | 98.7 |

| Ia2 | 227 | 95.9 |

| Ib1 | 2530 | 88.0 |

| Ib2 | 950 | 78.8 |

| IIa | 881 | 68.8 |

| IIb | 2375 | 64.7 |

| IIIa | 160 | 40.4 |

| IIIb | 1949 | 43.3 |

| IVa | 245 | 19.5 |

| IVb | 189 | 15.0 |

Data from the Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynaecological Cancer. Patients treated 1996-1998. J Epidemiol Biostat 83:41-78, 2003.

Goldie S.J., Kim J.J., Wright T.C. Cost effectiveness of human papillomavirus DNA testing for cervical cancer screening in women aged 30 years or more. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:619-631.

Hacker N.F. Cervical cancer. In Berek J.S., Hacker N.F., editors: Practical Gynecologic Oncology, 5th ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009.

Koutsky L.A. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papilloma virus to prevent high grade cervical lesions. The Future II Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1915-1927.

Rocconi R.P., Estes J.M., Leath C.A.III, et al. Management strategies for stage IB2 cervical cancer: A cost-effective analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:387-394.

Rose P.G., Bundy B., Watkins E.B., et al. Concurrent cisplatin-based radiotherapy and chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1144-1153.

Shepherd J.H., Spencer C., Herod J., Ind T.E.J. Radical vaginal trachelectomy as a fertility-sparing procedure in women with early stage cervical cancer—cumulative pregnancy rate in a series of 123 women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;113:719-724.

Primary Prevention

Primary Prevention Screening of Asymptomatic Women

Screening of Asymptomatic Women

Cervical Carcinoma in Pregnancy

Cervical Carcinoma in Pregnancy