Chapter 25 Cervical Cancer

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the third most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States. In 2011, 12,710 new cases and 4290 deaths1 are expected in the United States. However, in the underdeveloped world where screening remains underutilized, cervical cancer is the second most common cancer in women, with 275,000 deaths worldwide in 2002.2

In the past 50 years, there has been a steep decline in mortality from cervical cancer that can be attributed to the use of the Papanicolaou (Pap) smear, one of the most effective and widely used screening tests. However, exfoliative cytology obtained with the Pap smear permits early detection of only early squamous cell carcinoma; this has led to a relative increase in the incidence of cervical adenocarcinoma.3

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

There are numerous predisposing factors in the development of cervical cancer; however, early epidemiologic studies implicated an infectious agent as the most important factor. In 1983, this was identified as human papillomavirus (HPV). Although HPV infection is widespread, the majority of infections are cleared by cell-mediated immunity within 2 years and less than 10% of individuals will develop persistent infection. It is this persistent infection with HPV that plays a central role in the development of cervical cancer and can be identified in almost all cases. There are numerous HPV genotypes, of which HPV-16 and -18 have been determined as the most potent carcinogens. HPV-16 alone accounts for almost 60% of cervical cancers.3 In addition to its causative role in the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix, HPV has also been implicated in the development of cervical adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma.

Anatomy and Pathology

Cervix

The uterus has three distinct anatomic parts: the corpus or body, the lower uterine segment, and the cervix. The cervix is divided into suprvaginal and vaginal portions. The vaginal portion, or portio vaginalis, is covered by stratified nonkeratinized squamous epithelium, which also lines the vagina. This meets the columnar epithelium of the endocervix at the external os. This is the squamocolumnar junction, or transformation zone, described previously. In this area, a gradual transformation of columnar to squamous epithelium proceeds through life, leading to a gradual migration of this zone from the level of the external os in young women to a position within the endocervical canal in older women. This has consequences on the location of squamous tumors, which may present as endocervical masses in older women.

Pelvic Anatomy

A basic overview of pelvic anatomy is important for staging cervical cancer because an understanding of pelvic ligaments, vessels, peritoneal reflections, and pelvic lymph node stations is vital in evaluating cross-sectional computed tomography (CT) and MRI.4

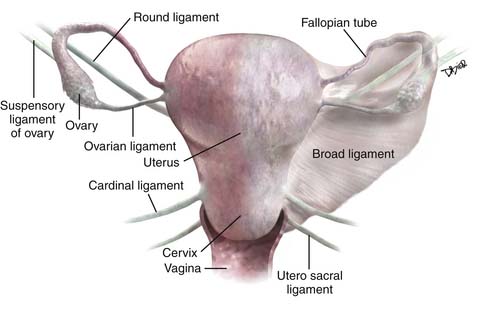

The important ligaments from the imaging perspective that are found in relation to the uterus, cervix, and ovaries include the broad ligament, round ligaments, uterosacral ligaments, cardinal ligaments, and suspensory ligament of the ovary (Figure 25-1).

The broad ligament is a peritoneal reflection that extends from the uterus to the pelvic sidewall. It contains the fallopian tubes along the upper margin; the cardinal ligament runs in the base of the broad ligament. It contains fat, connective tissue, the uterine and ovarian vessels, lymphatics, and the ovarian and round ligament. It is difficult to see except in the presence of ascites. The round ligament runs from the anterior wall of the uterus through the inguinal canal to the labia and is easy to see on CT. The cardinal ligament is an important structure that runs from the cervix and upper vagina to the obturator internus muscle. The uterine arteries run along the superior aspect of this ligament and help define this structure. As these arteries course from their origin from the internal iliac arteries to the edge of the uterus, they arch over the ureters creating the “arc sign,” which can frequently be seen on CT. The uterosacral ligament arises from the cervix and upper vagina to arc on either side of the rectum to the S2-S3 segments of the sacrum. This structure is thickened after radiation therapy. The suspensory ligament of the ovary carries the gonadal vessels to the ovary and is defined by the course of these vessels on cross-sectional imaging.

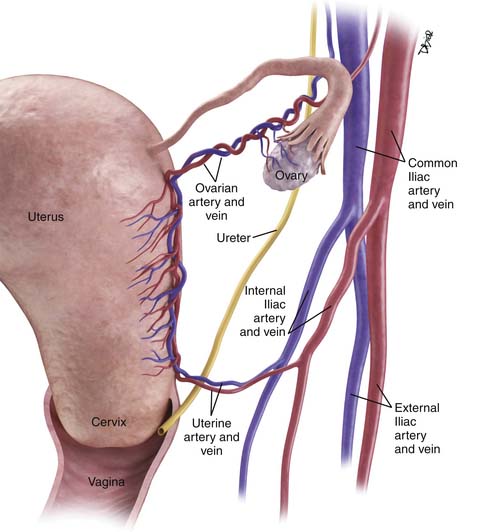

The main vascular supply to the uterus is the uterine arteries that arise from the internal iliac vessels, run along the superior aspect of the cardinal ligament, and then ascend on either side of the uterus to trifurcate and supply the fallopian tubes, fundus of the uterus, and ovaries (Figure 25-2). The ovarian arteries arise from the aorta below the renal arteries; the vaginal arteries arise from the internal iliac arteries.

Pelvic Nodal Anatomy

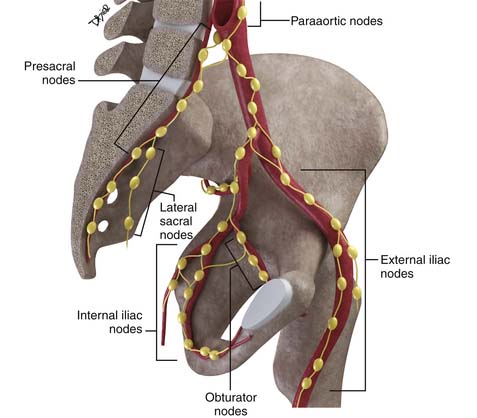

Disease spread to pelvic nodes is the most common pathway of tumor dissemination from the cervix. An understanding of the pathways of spread is essential for image analysis because these are the nodes that should be most closely scrutinized when evaluating cross-sectional imaging studies (Figure 25-3).

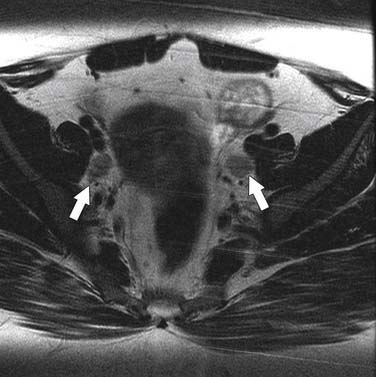

The nodal group most commonly first involved by tumor spread from pelvic tumors is the perivisceral nodes, which in the instance of cervical cancer are the parametrial nodes. This is followed by spread to pelvic sidewall nodes. Lymphatic spread from cervical tumors can spread to the pelvic nodes by three routes: (1) the lateral pathway of spread toward external iliac nodes, (2) the hypogastric route toward nodes along the internal iliac vessels, and (3) the posterior route, where lymphatics course along the uterosacral ligament to nodes along lateral sacral vessels and nodes anterior to the sacral promontory.5 The nodes along the external iliac vessels are subclassified into middle, medial, and lateral groups. The lateral chain nodes are located, as the name implies, lateral to the vessels; the middle chain nodes are between the external iliac artery and vein; and the medial chain nodes are located posterior and medial to the artery and vein. The nodes medial to the external iliac arteries are the group most commonly involved by metastatic spread from cervical cancer. These nodes are located in close proximity to nodes along the obturator vessels and are frequently grouped together with obturator nodes, although there is some controversy in this regard (Figure 25-4). All the pelvic nodal chains drain to the common iliac nodes. The common iliac nodes are also classified similar to external iliac nodes into middle, lateral, and medial subgroups. The middle subgroup is located posterior to the common iliac vein in the lumbosacral fossa, which is bordered posteriorly by the sacral vertebral body.6 This node is in close proximity to the L5 nerve root and can impinge on this root when enlarged, causing back pain (Figure 25-5). Spread from common iliac nodes is most commonly to the para-aortic nodes.

Key Points Anatomy, pathology, and epidemiology

• Persistent infection with HPV-16 and -18 is the most important risk factor in the development of cervical cancer.

• Cervical cancer has a long premalignant phase and, therefore, is accessible to early intervention and screening.

• Squamous carcinoma accounts for 85% of cervical tumors and arises from the zone located at the level of the external os and may present as exophytic or infiltrative masses.

• The uterine arteries and ureters as they course on the surface of the cardinal ligament define the level of the supravaginal cervix and site of parametrial invasion.

Patterns of Tumor Spread

As with all tumors, it is important to define regional and nonregional nodal groups; involvement of the latter upstages the tumor to stage IV because these nodes are viewed as M1 nodes. In the case of cervical cancer, parametrial, internal iliac, obturator, external iliac, common iliac, presacral, and lateral sacral are viewed as regional nodes, whereas inguinal, para-aortic, mediastinal, and supraclavicular are viewed as nonregional nodes, and consequently, qualify as metastatic disease.6

Key Points Patterns of tumor spread

• The most common pathways of tumor spread are direct invasion through the cervical stroma into the parametrium and adjacent pelvic structures and lymphatic spread.

• Nodal spread in cervical cancer occurs in a stepwise progressive manner from the parametrial to external, presacral, or internal iliac nodes followed by common iliac and para-aortic nodes.

• Para-aortic and inguinal adenopathy constitute nonregional nodes and, consequently, metastatic disease.

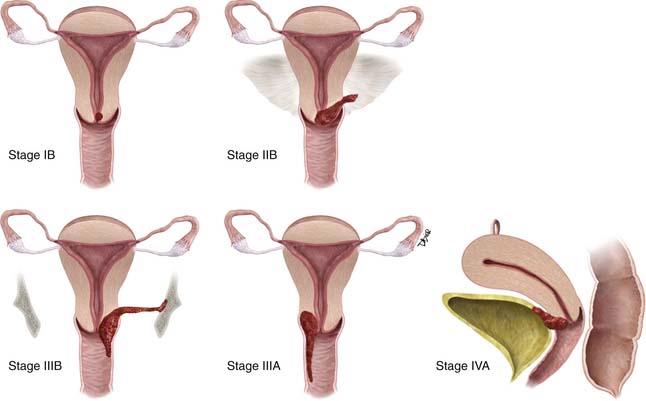

Staging

Unlike most other tumors, the staging of cervical cancer is primarily clinical, using the classification by the Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) committee. This is because, in most countries where this disease is prevalent, elaborate cross-sectional staging techniques such as MRI, CT, and positron-emission tomography (PET)/CT are not available. Consequently, to maintain some uniformity between clinical trials across nations, the basis for initial staging is the clinical stage. The classification has undergone numerous revisions. This chapter references the most recent 2009 revision (Figure 25-6). Some important facts about the FIGO staging is that it applies only to squamous carcinoma; the clinical stage is determined prior to the start of therapy and cannot be changed because of subsequent findings once treatment is started. For evaluation of the T (tumor) stage, the following examinations are recommended: physical examination, preferably as an examination under anesthesia; colposcopy; cystoscopy; proctoscopy; intravenous urography; and chest x-ray. Suspected involvement of the rectal or bladder mucosa must be confirmed by biopsy. The tumor size plays an important prognostic role; consequently, subgroups have been created in both stages I and II for tumors less than 4 cm (T1a&b1 and T2a1) or greater than 4 cm (T1b2 and T2a2) in the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) and FIGO classifications. It is noted that the definition of T categories corresponds to stages accepted by the FIGO classification (Table 25-1).7 A limitation of the clinical system of staging is that, compared with surgical staging, it can be erroneous in up to 32% of patients with stage IB and 65% of patients with stage III disease.8,9

| TNM CATEGORIES | FIGO STAGES | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Tumor (T) | ||

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed | |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | |

| Tis* | Carcinoma in situ (preinvasive carcinoma) | |

| T1 | I | Cervical carcinoma confined to uterus (extension to corpus should be disregarded) |

| T1a† | IA | Invasive carcinoma diagnosed only by microscopy. Stromal invasion with a maximum depth of 5.0 mm measured from the base of the epithelium and a horizontal spread of 7.0 mm or less. Vascular space involvement, venous or lymphatic, does not affect classification |

| T1a1 | IA1 | Measured stromal invasion 3.0 mm or less in depth and 7.0 mm or less in horizontal spread |

| T1a2 | IA2 | Measured stromal invasion more than 3.0 mm and not more than 5.0 mm with a horizontal spread 7.0 mm or less |

| T1b | IB | Clinically visible lesion confined to the cervix or microscopic lesion greater than T1a/IA2 |

| T1b1 | IB1 | Clinically visible lesion 4.0 cm or less in greatest dimension |

| T1b2 | IB2 | Clinically visible lesion more than 4.0 cm in greatest dimension |

| T2 | II | Cervical carcinoma invades beyond uterus but not to pelvic wall or to lower third of vagina |

| T2a | IIA | Tumor without parametrial invasion |

| T2a1 | IIA1 | Clinically visible lesion 4.0 cm or less in greatest dimension |

| T2a2 | IIA2 | Clinically visible lesion more than 4.0 cm in greatest dimension |

| T2b | IIB | Tumor with parametrial invasion |

| T3 | III | Tumor extends to pelvic wall and/or involves lower third of vagina, and/or causes hydronephrosis or nonfunctioning kidney |

| T3a | IIIA | Tumor involves lower third of vagina, no extension to pelvic wall |

| T3b | IIIB | Tumor extends to pelvic wall and/or causes hydronephrosis or nonfunctioning kidney |

| T4 | IVA IV any T/any N/M1 disease | Tumor invades mucosa of bladder or rectum, and/or extends beyond true pelvis (bullous edema is not sufficient to classify a tumor as T4) |

* FIGO no longer includes stage 0 (Tis).

† All macroscopically visible lesions—even with superficial invasion—are T1b/IB.

From Cervix uteri. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010:395–402.

The patterns of nodal spread have been described in a previous section; regional nodes for cervical cancer include obturator, internal iliac, external iliac, and common iliac.6 As previously mentioned, spread to para-aortic nodes constitutes metastatic spread. Another essential fact in assessment of the pathologic nodal status (pN) for the TNM classification is the number of nodes removed. At least six nodes must be available in the resected specimen; if the number of nodes is less than six, it qualifies as an NX, nodal status cannot be assessed.7

The definition of metastatic spread in the TNM or IVB in the FIGO classification includes invasion of bladder or rectal mucosa and distant spread. In the context of cervical cancer, distant spread most frequently presents as para-aortic, supraclavicular or mediastinal nodes, peritoneal spread, or involvement of lung, liver, or bones.

Key Points Staging

• FIGO staging of cervical cancer is clinical and does not incorporate nodal status.

• Tumor size and nodal involvement are the most important prognostic indicators.

• NCCN guidelines suggest use of cross-sectional imaging to facilitate treatment planning, although the initial clinical staging remains unchanged.

Imaging

A multi-institutional trial found that the overall accuracy of MRI and CT in the preoperative staging of early cervical cancer were comparable; however, in single institution studies, MRI is the most accurate technique for local staging of cervical cancer.10 The primary objective is to define tumors with parametrial invasion that precludes surgical resection and directs patients toward radiation and chemotherapy. MRI has proved to be the most effective technique in this regard with a high negative predictive value.

Primary Tumor

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is more useful than CT because of its superior soft tissue resolution. Its primary role is in determining tumor size, evaluating parametrial invasion, evaluating extent of uterine and vaginal involvement, and determining the involvement of adjacent pelvic structures. The patients who most benefit from an MRI are those with endocervical tumors, tumors larger than 2 cm at clinical examination, possible parametrial invasion, and pregnant patients.11

Technique

The basic principles of high-quality MRI for staging of pelvic tumors are fundamentally similar whether staging cervical, endometrial, or rectal cancer (Table 25-2). These rely on small–field of view, high-resolution T2-weighted images obtained perpendicular to the plane of the tumor, preferably in two orthogonal planes. This entails using thin sections, preferably 3 to 4 mm, with a small field of view of 16 to 20 mm. Consequently, the most important sequence for evaluation of parametrial invasion is the oblique thin-section T2-weighted image obtained at right angles to the axis of the tumor, most importantly, the supravaginal portion of the cervix.

| Protocol |

| Coronal T2-weighted images. |

| Axial T1-weighted images (large FOV). |

| Axial and sagittal T2-weighted images FOV 20-24. |

| Oblique axial T2-weighted images FOV 18-24 3 mm contiguous cuts. |

| Optional |

| Sagittal dynamic 3D LAVA images. |

| Postcontrast axial T1-weighted images. |

| It is recommended that the large FOV axial images be obtained from the level of the kidneys down through the pelvis to evaluate for retroperitoneal adenopathy and hydronephrosis. |

FOV, field of view; LAVA, liver acquisition with volume acceleration; 3D, three-dimensional.

Intravenous contrast has limited value in the staging of cervical tumors. It has no role in evaluation of parametrial invasion; however, it can be used to assess involvement of adjacent structures such as the bladder. The dynamic images show small tumors as hypervascular lesions and have a reported high accuracy in determining depth of stromal invasion in small tumors.12 However, larger tumors appear as centrally hypovascular with only marginal enhancement.

Evaluation of Images

Stage I

For tumors confined to the cervix, the smaller microinvasive tumors fall into category IA. In this subgroup, the role of imaging is limited, although there has been some work with dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI that identified tumors with greater than 4 mm depth of penetration into the stroma as hypervascular lesions.12 The larger tumors that fall into the IIB category are seen on T2-weighted images as hyperintense masses that invade the hypointense stroma. However, in younger women, the stroma is occasionally hyperintense and the tumors may be harder to delineate. The size of tumors is an important prognostic indicator; this is reflected by the decline in 5-year survival rate from 84% to 66% in tumors larger than 3 cm.13 The larger tumors are also associated with an increased likelihood of nodal spread. The assessment of tumor size by MRI has an excellent correlation with size assessed by pathology.

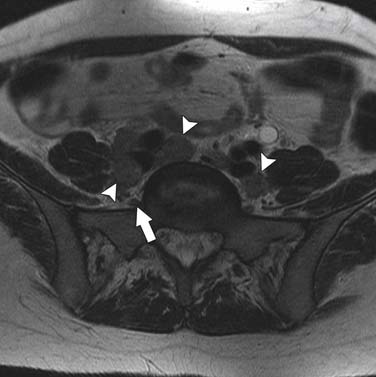

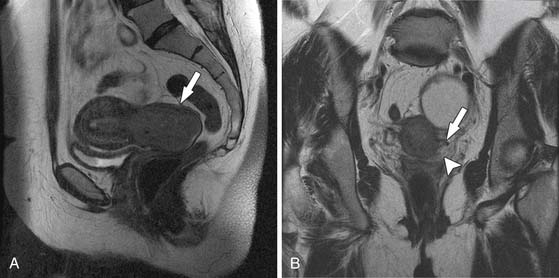

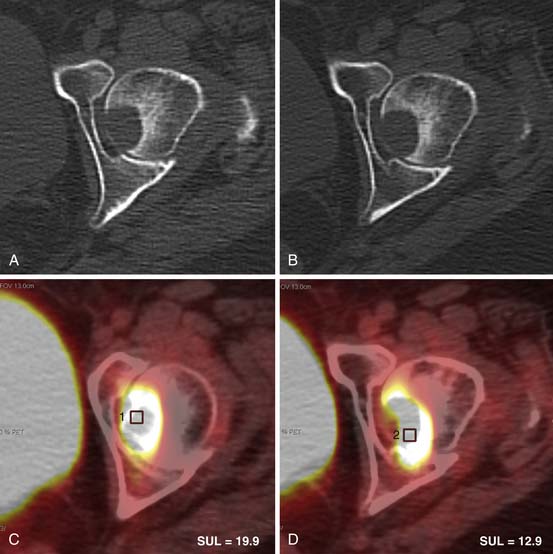

Stage II

The most important information from the perspective of treatment planning is evaluation of parametrial invasion, the presence of which excludes surgical resection. In the assessment of parametrial invasion, MRI has a high negative predictive value (94-100%) with an intact dark stromal ring virtually excluding paramtrial invasion (Figure 25-7).13,14 Disruption of the cervical ring generally indicates parametrial invasion, with additional signs such as spiculated tumor-parametrium interface and abutment of uterine vessels improving diagnostic confidence (Figures 25-8 and 25-9). An important limitation to keep in mind is that large tumors may be associated with peritumoral edema, which can be mistaken for parametrial invasion. This leads to a decline in staging accuracy from 90% for small lesions to 70% for larger tumors.13,14 This important fact should be kept in mind at the time of image evaluation.

The assessment of invasion of the lower uterine segment can be obtained with MRI. Although it does not fall into information required for staging, it is important in young women who wish to retain fertility and are considering trachelectomy. MRI predicts the relationship of the tumor to the internal os with high accuracy.15

Stage III

In stage III, a vaginal involvement extends into the lower third of the vagina, and in IIIB, the extension is laterally until the pelvic sidewall. This lateral extension is generally associated with entrapment of the ureters and development of hydronephrosis. The MRI findings that suggest pelvic sidewall involvement include tumor within 3 mm of or abutment of the pelvic sidewall musculature.16,17 MRI findings in vaginal involvement have been mentioned previously.

Stage IV

Invasion of adjacent pelvic structures such as the bladder or rectum or development of distant spread qualifies as stage IV disease. MRI has a high negative predictive value in excluding bladder or rectal involvement. However, the positive predictive value is lower. This is because abutment of the bladder or focal loss of the normal low signal of the bladder wall and development of hyperintense T2 foci along the anterior aspect of the posterior bladder wall do not always reflect tumor invasion. The sensitivity of bladder invasion is in the range of 71% to 100% and the specificity is in the range of 88% to 91%.18,19 This limitation has led to an evaluation of dynamic MRI, and some studies have suggested that this leads to improved accuracy over evaluation of only T2-weighted images.20 The more advanced cases of bladder invasion are relatively easier to diagnose as defined by nodular masses projecting into the bladder or development of a vesicovaginal fistula.

It is noted that recent multi-institutional studies have found both CT and MRI suboptimal in evaluating depth of stromal invasion, parametrial extension, and pelvic nodal metastasis. These studies also report lower accuracies for MRI staging than those seen in single-institution studies. However, the accuracy for assessment of tumor size and lower uterine invasion remains high, It is to be noted that the technique used in these studies did not incorporate high-resolution T2 scans or imaging in the orthogonal plane, which is important in the assessment of parametrial invasion.10,21,22

Computed Tomography

CT has limited value in the assessment of local disease because 50% of the tumors are isodense to the cervical stroma on contrast-enhanced CT. CT is also suboptimal in its ability to distinguish tumor from normal parametrial structures leading to overestimation of parametrial involvement.23

Key Points Imaging of primary tumor

• Parametrial invasion and nodal spread are the most important factors to be evaluated on imaging and determine whether treatment will be surgical versus nonsurgical and the extent of treatment.

• T2-weighted images obtained perpendicular to the cervical lumen are key to the evaluation of parametrial invasion.

Lymph Node Involvement

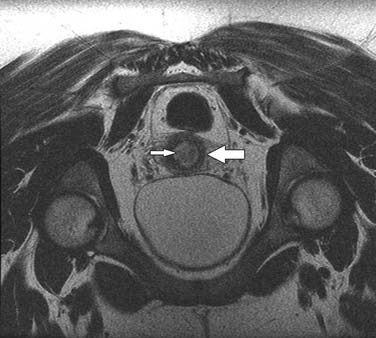

The presence and extent of nodal involvement are the most important prognostic factors in cervical cancer. In surgically treated cervical cancer, survival rates decline from 85% to 90% to 50% to 55% in the presence of nodes that are positive for tumor. In addition, the presence of metastatic adenopathy is important in treatment planning, defining radiation ports, and assessing need for and extent of surgical resection. It has been established in a multi-institutional study that the incidence of metastatic adenopathy in early cervical cancer stage IIA and below is in the range of 32%.22 The breakup of the likelihood of nodal metastasis on the basis of stage is less than 1% with stromal invasion less than 3 mm. However, in the presence of stromal invasion between 3 and 5 mm, this increases to 7%. In the larger tumors stage IB2, this increases to 20% to 25%.

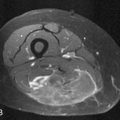

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Evaluation of Nodal Involvement

CT and MRI have comparable accuracies in the range of 83% to 85% in the assessment of nodal involvement. This is because both techniques rely on nodal enlargement as the criterion for malignant involvement. The limitation of both techniques is a low sensitivity in the range of 24% to 70%, which is due to the inability to detect metastasis in normal-sized nodes. However, although neither technique can distinguish inflammatory from malignant nodes, the specificity is reportedly high, in the range of 89% to 93%. It has been observed that there is an up to 27% incidence of necrotic adenopathy in cervical cancer.24 The detection of necrotic nodes is more easily done with MRI. This finding, when seen, has a high specificity for the presence of metastasis. In an effort to improve accuracy in the assessment of nodal involvement, a variety of new MRI techniques are being evaluated, including the use of ultrasmall supraparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) particles and diffusion-weighted imaging. The use of USPIO particles has been reported to improve sensitivity on MRI from 29% to 93%; however, this agent is currently not available in the United States.25 There is also some initial work to suggest that calculation of apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values on diffusion-weighted images improved sensitivity of nodal involvement; however, this needs to be more extensively evaluated.26

At our institution, we believe that, in the assessment of nodal disease, it is important to incorporate the location of nodes into the evaluation of involvement. In other words, nodes along the anticipated pathways of spread such as the obturator, internal iliac, and common iliac should be scrutinized with a higher sensitivity than areas in which it is less common for spread to occur such as the lateral chain external iliac nodes. In addition, location of the tumor should also be incorporated into the assessment—for instance, if extension into the lower third of the vagina has occurred, the superficial inguinal nodes should be carefully assessed. Nodal morphology is also important in improving specificity and can be best assessed with the use of high-resolution (small–field of view/thin-section) images. The morphologic features most useful for assessing metastatic adenopathy are irregular or spiculated margins and, as mentioned previously, heterogeneity of the nodal signal characteristics.27

Positron-Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography

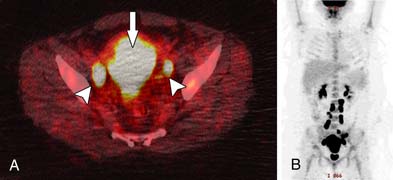

In view of the low sensitivity of cross-sectional imaging in the evaluation of nodal involvement, efforts have been made to improve accuracy with the use of functional imaging modalities such as PET/CT.

The use of PET/CT has improved the accuracy of staging in that it has a high specificity in the detection of nodal metastasis. In addition, it improves sensitivity from the low sensitivities reported with MRI and CT to 83% to 91%; however, the problem with micrometastasis remains an issue. Metastatic nodes smaller than 5 mm are generally negative on PET.28

The role of PET/CT in advanced cervical tumors is supported in a number of studies.29,30 It establishes the presence of para-aortic adenopathy with high accuracy (Figure 25-10). It adds to the information available on CT, either by identifying nodes that were not enlarged on CT or by defining unexpected sites of disease. However, the value of PET in primary lymph staging is related to a high pretest probability of distant spread and is primarily in patients with locally advanced disease. Its role in early resectable cancer stages IA to IIA is questionable because the sensitivity has been found to be low, in the range of 10% to 53%.31,32

Key Points Lymph node staging

• CT and MRI have comparable accuracies in the evaluation of nodal involvement because both rely on nodal size as the criterion for assessment.

• Newer techniques such as the use of USPIO and diffusion-weighted images have the potential to improve accuracy; however, this remains to be proved with more studies.

• PET/CT improves the assessment of nodal involvement in patients with advanced disease but has no value in early-stage cervical cancer.

Treatment

Concurrent Chemoradiation

In 1999, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) consensus established the standard of care in the United States, which is still valid today (available online at http://www.nih.gov/news/pr/feb99/nci-22.htm). The addition of platinum-based chemotherapy with radiation improved survival by approximately 10%.33–35 For the last 10 years, there has been very little outcome improvement for women with cervical cancer.

A meta-analysis that included 4580 patients from 19 randomized trials confirmed the NCI consensus. If modern radiation facilities are available, concurrent chemoradiation is superior to radiotherapy alone in terms of higher local control and decreased incidence of distant relapses with both platinum and nonplatinum chemotherapy.36

Chemotherapy Considerations

Most chemotherapy regimens for cervical cancer are based on the use of cisplatin. Two regimens are recommended by the NCI 1999 consensus: either weekly cisplatin at 40 mg/m2 for six doses or two cycles of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil during days 1 through 5 and days 22 through 26 of radiation.2,11 The most commonly used regimen is cisplatin at a dose of 40 mg/m2 for 6 weeks during radiation treatment. The number of cisplatin chemotherapy cycles is independently predictive of progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Patients who received fewer than six cycles of cisplatin have a worse PFS and OS. In addition, advanced stage, longer time to radiotherapy completion, and absence of brachytherapy are associated with decreased PFS and OS (P < .05).

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Followed by Surgery

The administration of chemotherapy, in a neoadjuvant setting, reduces tumor volume, potentially kills micrometastases, and renders radical surgery feasible in initially inoperable cases. The rationale for neoadjuvant chemotherapy is that a viable tumor will be more sensitive to the cytocidal effects of the anticancer drugs because of the uncompromised blood supply. A meta-analysis of individual patient data reviewed the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery compared with radiotherapy alone.36 The combined results from five trials indicated a highly significant reduction in the risk of death with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, despite some differences in design and results between trials in a population of 872 women. The timing and dose intensity of the cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy are essential, with a dose-dense strategy being the most beneficial. Dose-dense neoadjuvant chemotherapy was investigated in a randomized study of 142 patients. The regimen was well tolerated with an overall clinical response rate of 69.4%. Benefits included reduction in tumor size, elimination of pathologic risk factors, and improvement of prognosis in responding patients. Dose-dense also avoids delays of other primary treatments for nonresponders.

Two phase II studies compared neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery to chemoradiation.37,38 No difference in outcome was observed. Randomized phase III studies are ongoing to definitely answer whether this strategy is also optimal. When modern radiation facilities are not available or according to patient preference, neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to radical surgery is an acceptable treatment approach.

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Followed by Radiotherapy

This sequential therapy has been studied for 30 years. A meta-analysis showed a trend for inferior survival when this treatment strategy was used.40 Altered growth kinetics after chemotherapy probably decreases the effectiveness of radiotherapy.

Recently, a new meta-analysis of 2946 patients reviewed data from 23 trials. When chemotherapy cycle lengths are 14 days or shorter (P = .046) or when cisplatin dose intensities are greater than or equal to 25 mg/m2 per week (P = .20), this treatment approach provides a survival advantage in favor of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Longer cycle lengths or low cisplatin dose are detrimental. The meta-analysis reported an increase of 7% in the 5-year survival with chemotherapy cycles shorter than 14 days versus an 8% decrease in 5-year survival for those treated with longer cycles. The absolute reduction in the 5-year survival for the group with low intensity was 11%, whereas in the second group with high-dose intensity, an increase of 3% in 5-year survival was noted. Adjuvant neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radiation, even with a dose-dense strategy, is not recommended until further clinical data are available from a randomized study comparing neoadjuvant dose dense prior to radiation with concurrent chemoradiation.41

Role of Adjuvant Chemotherapy after Completion of Primary Treatment

There are scant data to support adjuvant chemotherapy after completion of concurrent chemoradiation or neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery. This topic is currently under active clinical investigation. The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group is sponsoring a trial of four courses of chemotherapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin every 21 days versus observation after concurrent chemoradiation in patients with positive pelvic or para-aortic nodes or invasion of the parametrium that is completely resected in patients who have undergone radical hysterectomy for clinical stage IA2, IB, or IIA disease. Another phase III study evaluated the role of gemcitabine in addition to cisplatin during chemoradiation followed by two courses of adjuvant gemcitabine and cisplatin in patients with stage IB2 and greater.41 This study showed a significantly improved survival for the gemcitabine addition arm compared with concurrent radiation with single-agent cisplatin. Survival outcome results in the control arm are consistent with those reported in other studies of concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for cervical cancer, suggesting that the superiority of the gemcitabine-containing arm is not due to underperformance of the control arm. The main survival improvement was related to improved distant control with the gemcitabine-containing regimen. However, the rate of adverse events was increased with the addition of gemcitabine, but grade 3 to 4 events were clinically manageable in the context of a survival benefit. This study does not dissociate the adjuvant chemotherapy with the addition of gemcitabine during chemoradiation. Patients with a poor response to initial multidisciplinary treatment may benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy, but results of randomized studies are necessary before this strategy is used as a standard of care.

Treatment of Stage IV Disease

Key Points Management strategies for patients with primary cervical cancer

Advanced Disease

• Primary chemoradiation, which is the standard of care in the United States

• Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, followed by radical hysterectomy and subsequent chemoradiation as indicated

• In very selected cases, primary radical hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy followed by tailored radiotherapy with concomitant chemotherapy

Treatment of Recurrence

An isolated metastasis should be treated with curative intent. If the recurrence is small (<3 cm), chemoradiation is used. For larger areas, the lesion should be resected first and followed by chemoradiation. If the lesion is unresectable because of location or size, neoadjuvant chemotherapy with the combination of drugs that offers the best chances of response should be used, followed by surgery if the patient has a response.

Patients with multiple sites of metastases should be enrolled in a clinical trial. Patients who are ineligible for clinical trials should be offered a simple palliative chemotherapy focusing on minimizing morbidity. For recurrent cervical cancer, the current treatment remains carboplatin and paclitaxel.42 Non–platinum-based regimens are being explored in patients with recurrent disease who had prior platinum exposure.43

New Therapies

Bevacizumab, a monoclonal antivascular endothelial growth factor antibody, and pazopanib, a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor, have been evaluated in clinical trials and have increased the progression-free interval in patients with recurrent disease.44,45 Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors are ineffective in patients with refractory cervical cancer.46 Cetuximab, a monoclonal inhibitor of the extracellular domain of EGFR, may have a modest efficacy in patients with refractory recurrence.47,48

Surveillance

Traditionally, CT is the most widely used modality in the follow-up of patients. However, it is limited in distinguishing posttreatment change from tumor.49 The presence of baseline posttreatment scans can somewhat obviate this problem by providing a comparison for follow-up CT scans. Any interval change identified on subsequent scans raises the possibility of recurrent disease.

MRI with superior soft tissue resolution has some advantages over CT, particularly when combined with dynamic scanning. The combination of T2-weighted images and early enhancement on dynamic scanning (<90 sec) has a high sensitivity (91%) but the specificity, although improved over evaluation with only T2-weighted images, remains low (67%).50

Recent reports suggest that PET/CT detects recurrence earlier than CT or MRI.51 Studies using PET for surveillance of patients with no evidence of disease after primary treatment found a high sensitivity (90.3%) but a lower specificity (76.1%) for detection of recurrent disease. The recurrences were also detected earlier at 9 to 12 months than the historical average of 2 years, suggesting that this technique is more sensitive than previously used modalities and clinical examination. The additional value of PET/CT is the documentation of distant sites of disease, the presence of which could influence treatment decisions. The disadvantage of PET remains its low specificity and poor anatomic detail. Consequently, a reasonable strategy in the follow-up of patients with a high probability for recurrence would be to leverage the sensitivity of PET or MRI, supplemented by biopsy. If PET is used and identifies recurrence, an MRI of the pelvis should then be added in patients who are potential surgical candidates for pelvic exenteration or other radical surgeries. Alternatively, if MRI is the primary follow-up modality and if equivocal, a PET may be obtained to clarify the issue.

Key Points Surveillance

• Tumor recurrence is most common in the 2 years after primary treatment, and close follow-up should be obtained every 2 to 3 months during this time period.

• Three fourths of the recurrences are within the pelvis; the most common sites are the vaginal cuff, cervix, parametrium, and pelvic sidewalls.

1. Cancer Stat Fact Sheet. Cancer of the Cervix Uteri. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2011.

2. Parkin D.M., Bray F., Ferlay J., et al. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74-108.

3. Schiffman M., Castle P., Jeronimo J., et al. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet. 2007;370:890-907.

4. Folgasher M., Walsh J. CT anatomy of the female pelvis: a second look. Radiographics. 1994;14:51-66.

5. Kaur H., Silverman P., Iyer R., et al. Diagnosis, staging and surveillance of cervical carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:1621-1631.

6. McMohan C., Rofsky N.M., Pedrosa I. Lymphatic metastasis for pelvic tumors: anatomic classification, characterization and staging. Radiology. 2010;254:31-46.

7. Cervix uteri. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010:395-402.

8. Lagasse L.D., Creasman W.T., Shingleton H.M., et al. Results and complications of operative staging in cervical cancer: experiences of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol. 1980;9:90-98.

9. Van NagellJr., Roddick J.W.Jr., Lowin D.M. The staging of cervical cancer: inevitable discrepancies between clinical staging and pathologic findings. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110:973-978.

10. Hricak H., Gatsonis C., Chi D., et al. Role of imaging in pretreatment evaluation of early cervical cancer: results of the Intergroup Study American College of Radiology Imaging Network 6651—Gynecologic Oncology Group 183. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9329-9337.

11. Sala E., Wakely S., Senior E., et al. MRI of malignant neoplasms of the uterine corpus and cervix. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1577-1587.

12. Kojima Y., Yoichi A., Hiroaki K., et al. Carcinoma of the cervix: value of dynamic magnetic resonance imaging in assessing early stromal invasion. Int J Clin Oncol. 1998;3:143-146.

13. Hricak H., Lacey C.G., Sandles L.G., et al. Invasive cervical carcinoma comparison of MR imaging and surgical findings. Radiology. 1998;166:623-631.

14. Kim S.H., Choi B.I., Lee H.P., et al. Uterine cervical carcinoma: comparison of CT and MR findings. Radiology. 1990;175:45-51.

15. Peppercorn P.D., Jeyarajah A.R., Woolas R., et al. Role of MR imaging in the selection of patients with early cervical cancer for fertility preserving surgery: initial experience. Radiology. 1999;212:395-399.

16. Togashi K., Morikawa K., Kataoka L.M., et al. Cervical cancer. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1998;8:391-397.

17. Hricak H., Yu K.K. Radiology in invasive cervical cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:1101-1108.

18. Bipat S., Glas A.S., van der Velden J., et al. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in staging of uterine cervical carcinoma: a systemic review. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91:59-66.

19. Rockall A.G., Ghosh S., Alexander-Sefre F., et al. Can MRI rule out bladder and rectal invasion in cervical cancer to help select patients for limited EUA? Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:244-249.

20. Hawighort H., Knapstein P.G., Weikel W., et al. Cervical carcinoma: comparison of standard and pharmokinetic MR imaging. Radiology. 1996;201:531-539.

21. Mitchell D.G., Snyder B., Coakley F., et al. Early invasive cervical cancer: tumor delineation by magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography and clinical examination, verified by pathologic results in the ACRIN 6651/GOG 183 intergroup study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5687-5694.

22. Hricak H., Gatsonis C., Coakley F., et al. Early invasive cervical cancer: CT and MR imaging in preoperative evaluation—ACRIN/GOG comparative study of diagnostic performance and interobserver variability. Radiology. 2007;245:495-498.

23. Kim S.H., Choi B.I., Kim J.K., et al. Preoperative staging of uterine cervical carcinoma: comparison of CT and MRI in 99 patients. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1993;17:633-640.

24. Yang W.T., Lam W.W., Yu M.Y., et al. Comparison of dynamic helical CT and dynamic MRI in the evaluation of pelvic nodes in cervical carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:759-766.

25. Rockall A.G., Sohaib S.A., Harisinghani M.G., et al. Diagnostic performance of nanoparticle-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of lymph node metastasis in patients with endometrial and cervical cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2813-2821.

26. Lin G., Ho K.C., Wang J.J., et al. Detection of lymph node metastasis in gynecologic cancer by diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging at 3 Tesla. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28:128-135.

27. Choi H.J., Seung H.K., San-Soo S., et al. MRI for pretreatment lymph node staging in uterine cervical cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W538-W543.

28. Sironi S., Picchio M., Perego P., et al. Lymph node metastasis in patients with clinical early stage cervical cancer: detection with integrated FDG PET/CT. Radiology. 2006;238:272-279.

29. Rose P.G., Adler L.P., Rodriguez M., et al. Positron emission tomography for evaluating para-aortic nodal metastasis in locally advanced cervical cancer before surgical staging: a surgicopathologic study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:41-45.

30. Chao A., Ho K.C., Wang C.C., et al. Positron emission tomography in evaluating the feasibility of curative intent in cervical cancer patients with limited distant lymph node metastases. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110:172-178.

31. Wright J.D., Dehdashti F., Herzog T.J., et al. Preoperative lymph node staging of early stage cervical carcinoma by FDG PET. Cancer. 2005;104:2484-2491.

32. Chou H.H., Chang T.C., Yen T.C., et al. Low value of FDG-PET in primary staging of early-stage cervical cancer prior to radical hysterectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:123-128.

33. Keys H.M., Bundy B.N., Stehman F.B., et al. Cisplatin, radiation, and adjuvant hysterectomy compared with radiation and adjuvant hysterectomy for bulky stage IB cervical carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1154-1161. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 1999;341:708

34. Morris M., Eifel P.J., Lu J., et al. Pelvic radiation with concurrent chemotherapy compared with pelvic and para-aortic radiation for high-risk cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1137-1143.

35. Rose P.G., Bundy B.N., Watkins E.B., et al. Concurrent cisplatin-based radiotherapy and chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1144-1153. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 1999;341:708

36. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from 21 randomised trials. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:2470-2486.

37. Whitney C.W., Sause W., Bundy B.N., et al. Randomized comparison of fluorouracil plus cisplatin versus hydroxyurea as an adjunct to radiation therapy in stage IIB-IVA carcinoma of the cervix with negative para-aortic lymph nodes: a Gynecologic Oncology Group and Southwest Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1339-1348.

38. Dueñas-González A., Lopez-Graniel C., Gonzalez-Enciso A., et al. Concomitant chemoradiation versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced cervical carcinoma: results from two consecutive phase II studies. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1212-1219.

39. Modarress M., Maghami F.Q., Golnavaz M., et al. Comparative study of chemoradiation and neoadjuvant chemotherapy effects before radical hysterectomy in stage IB-IIB bulky cervical cancer and with tumor diameter greater than 4 cm. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:483-488.

40. Shueng P.W., Hsu W.L., Jen Y.M., et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy should not be a standard approach for locally advanced cervical cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;40:889-896.

41. Dueñas-González A., Zarba J.J., Alcedo J.C., et al. A phase III study comparing concurrent gemcitabine (Gem) plus cisplatin (Cis) and radiation followed by adjuvant Gem plus Cis versus concurrent Cis and radiation in patients with stage IIB to IVA carcinoma of the cervix. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:CRA5507.

42. Monk B.J., Sill M.W., McMeekin D.S., et al. Phase III trial of four cisplatin-containing doublet combinations in stage IVB, recurrent, or persistent cervical carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4649-4655.

43. Tewari K.S., Monk B.J. The rationale for the use of non-platinum chemotherapy doublets for metastatic and recurrent cervical carcinoma. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2010;8:108-115.

44. Monk B., Mas L., Zarba J.J., et al. A randomized phase II study: Pazopanib (P) versus lapatinib (L) versus combination of pazopanib/lapatinib (L+P) in advanced and recurrent cervical cancer (CC). J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:A5520.

45. Monk B.J., Sill M.W., Burger R.A., et al. Phase II trial of bevacizumab in the treatment of persistent or recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1069-1074.

46. Goncalves A., Fabbro M., Lhomme C., et al. A phase II trial to evaluate gefitinib as second- or third-line treatment in patients with recurring locoregionally advanced or metastatic cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:42-46.

47. Kurtz J.E., Hardy-Bessard A.C., Deslandres M., et al. Cetuximab, topotecan and cisplatin for the treatment of advanced cervical cancer: A phase II GINECO trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113:16-20.

48. Farley J.H., Sill M., Walker J.L., et al. Phase II evaluation of cisplatin plus cetuximab in the treatment of recurrent and persistent cancers of the cervix: A limited access phase II study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:A5521.

49. Walsh J.W., Goplerud D.R. Prospective comparison between clinical and CT staging in primary cervical carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981;137:997-1003.

50. Kinkel K., Ariche M., Tardivon A.A., et al. Differentiation between recurrent tumor and benign conditions after treatment of gynecologic pelvic carcinoma: value of dynamic contrast-enhanced subtraction MR imaging. Radiology. 1997;204:55-63.

51. Ryu S.Y., Kim M.H., Choi S.C., et al. Detection of early recurrence with 18F-FDG PET in patients with cervical cancer. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:347-352.