Cerebrovascular accident

Definition

Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) is a clinical syndrome, of presumed vascular origin, typified by rapidly developing signs of focal or global disturbance of cerebral functions lasting more than 24 hours or leading to death (WHO 1978). If the symptoms of the lesion last less than 24 hours, the terms ‘transient ischaemic attack’ (TIA) or ‘mini stroke’ are used.

Epidemiology

Prevalence

The National UK Audit Office (DH 2006) reported that around 110 000 people suffer a stroke each year, at an overall cost to the economy of around £7 billion.

Aetiology

Ischaemia (80% of strokes)

Damage occurs as a result of a blockage of the arteries supplying the brain (S2.8). The most common causes are thrombosis formation or emboli. A thrombus is the formation of a blood clot inside an intact blood vessel which obstructs the flow of blood. This can occur in large vessels such as the internal carotid arteries, vertebral arteries and those that form the circle of Willis (S2.8) or in small deeper vessels when it is termed a lacunar stroke. An embolus occurs when an object (the embolus) migrates from one part of the body (through the circulation) and causes the blockage of a blood vessel in the brain. The main sources of an embolus are a thrombus, fat droplets (following a bone fracture) or air bubbles (cardiac artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), decompression sickness, or intravenous therapy).

Intracranial haemorrhage

Intra-axial

This involves bleeding inside the brain but outside the tissue. For example, an intraventricular haemorrhage which occurs into the ventricles (S2.8) following moderate to severe traumatic brain injuries and is usually associated with other extensive trauma.

Extra-axial

This involves bleeding inside the skull but outside of the brain, that is between the meninges (S2.8). For example:

Epidural haematoma (EDH): A bleed between the dura mater and the skull usually caused by trauma (commonly acceleration–deceleration), although spontaneous haemorrhage is known to occur.

Subdural haematoma (SDH): A bleed within the subdural space often caused by head injury, when fast changing velocities within the skull may stretch and tear small bridging veins across the subdural space (S2.8).

Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH): A bleed into the subarachnoid space (S2.8), most often caused by the rupture of an intracranial aneurysm (85%) typically at the junctions or bifurcation of the major cerebral blood vessels. Other causes include non-aneurysmal mid-brain haemorrhage (10%) and vascular abnormalities (arteriovenous malformation and vasculitis) (5%).

Pathology

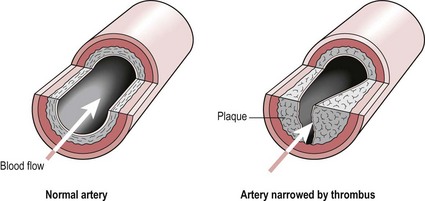

Thrombosis formation

A thrombus is a pathological process resulting in a blood clot forming within an intact blood vessel (Fig. 1.1). The following conditions lead to thrombus formation. A change in the blood vessel wall following trauma due to hypertension or the formation of an atheroma which leads to alterations in blood flow through the vessel. Simultaneously, a condition needs to exist that causes a change in the blood composition, for example, hypercoagulability disorders, smoking, hyperlipidaemia (raised lipoprotein levels), hypercholesterolaemia or diabetes. This combination of factors leads to aggregation of platelets to produce a platelet plug and the activation of clotting factors, which facilitates thrombus formation.

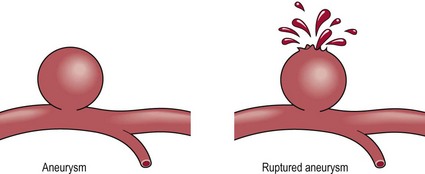

Aneurysm formation

An aneurysm is a localized, blood-filled dilation of a blood vessel (Fig. 1.2) caused by disease or weakening of the vessel wall. Aneurysms most commonly occur in arteries at the base of the brain, e.g. in the circle of Willis. Aneurysm formation is probably the result of multiple factors affecting the arterial wall, however the process is probably initiated by some weakness of the vessel wall and then compounded by the blood itself bombarding the inner surface. In effect, the aneurysm becomes self-perpetuating. Risk factors for an aneurysm include diabetes, obesity, hypertension, smoking, alcoholism, and copper deficiency (which affect the elastin component of the vessel wall).

Figure 1.2 Aneurysm formation.

Signs and symptoms

Stroke symptoms are typically of sudden onset with the presentation dependent upon the area of the brain affected. Understanding the function of the different areas of the brain (S2.7, 9, 10, 11, 12) and the blood vessels supplying them (S2.8) will give the therapist a platform by which to reason the potential clinical presentation.

The signs and symptoms presented will be a complex array of:

Cognitive and perceptual (S3.16, 17, 18, 33)

• Problems with colour, depth, figure ground, form constancy, size constancy

• Problems with spatial relations for example up/down, in/out, left/right, 2D/3D

• Altered body scheme, e.g. altered midline orientation, pusher syndrome

• Agnosia: problems with recall/recognition

• Poor memory: short-term or long-term memory

• Problems with higher executive functions, e.g. planning, organization, problem solving, self-initiation, monitoring and inhibition.

References and Further Reading

Coull, A, Lovett, J, Rothwell, P. Population based study of early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke: implications for public education and organization of services. British Medical Journal. 2004; 328:326–328.

Department of Health. Improving stroke services: a guide for commissioners. www.dh.gov.uk/publications, 2006. [Available from].

Furie, B, Furie, BC. Mechanisms of thrombus formation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008; 359:938–949.

Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party, Royal College of Physicians, National Clinical Guidelines for Stroke, ed 2. RCP, London, 2004. www.rcplondon.ac.uk

Stroke Association www.stroke.org.uk

WHO. Cerebrovascular disorders: a clinical and research classification. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1978.