Chapter 14 Cerebral Venous Thrombosis

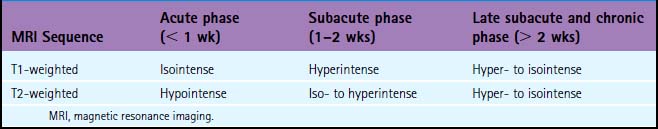

Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) was first described by Ribes in the early 19th century on the basis of postmortem examination.1 For a long time, CVT was seen as a rare and severe illness resulting in seizures, focal deficits, and often death. Its association with sinus infections was well described,2 but other predisposing conditions were not yet recognized. However, advances in vascular neuroimaging have led to a renewed appreciation of this disorder, which is more common, more variable, and less uniformly severe than previously assumed.3–6

Cerebral sinus venous thrombosis is estimated to account for 0.5% of all strokes in adults,3 but its true incidence is unknown, and frequent underrecognition is suspected.7 Initially asymptomatic venous sinus thrombosis has been implicated in the etiology of idiopathic intracranial hypertension.8,9 Indeed, studies have demonstrated that the most common symptom of CVT is headache (80%–90%) and the most common sign papilledema (50%–60%).10 Other clinical signs include focal deficits and partial seizures, and alteration of consciousness. Headache may be the only clinical symptom of CVT.11,12 Approximately one quarter of all patients have completely normal examination.3

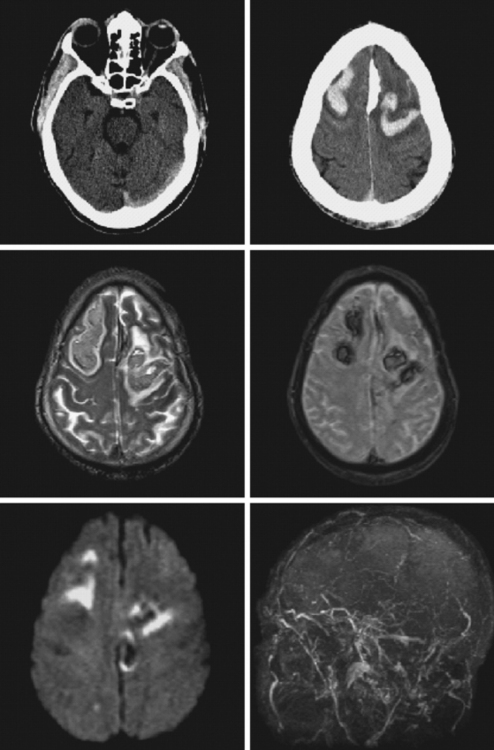

Multiple causes and risk factors for CVT have been identified.5 The list comprises genetic and acquired prothrombotic conditions (the latter most prominently including pregnancy, puerperium, and combination of hormonal contraceptives and smoking), infections (particularly sinusitis, otitis, mastoiditis, and meningitis), systemic inflammatory illnesses (such as systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, and inflammatory bowel disease), hematological disorders (e.g., polycythemia, leukemia, thrombocythemia, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria), systemic cancer, severe dehydration, and head trauma. The threshold for obtaining brain imaging to exclude CVT should be lower in the presence of these conditions.

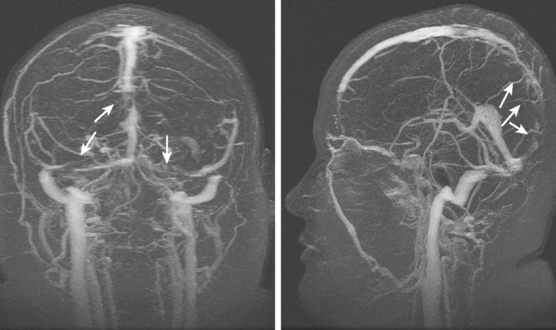

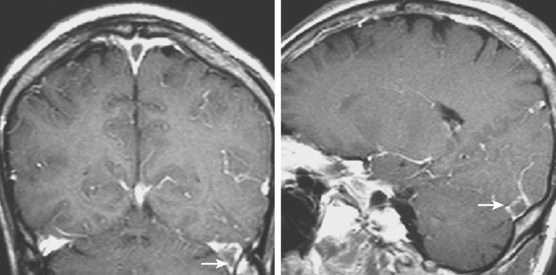

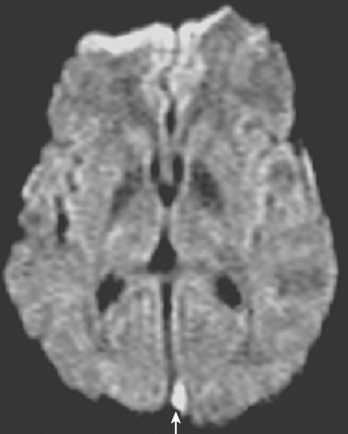

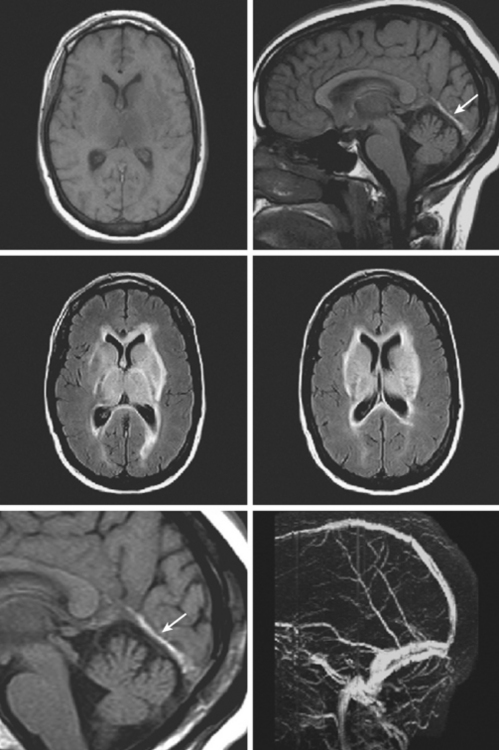

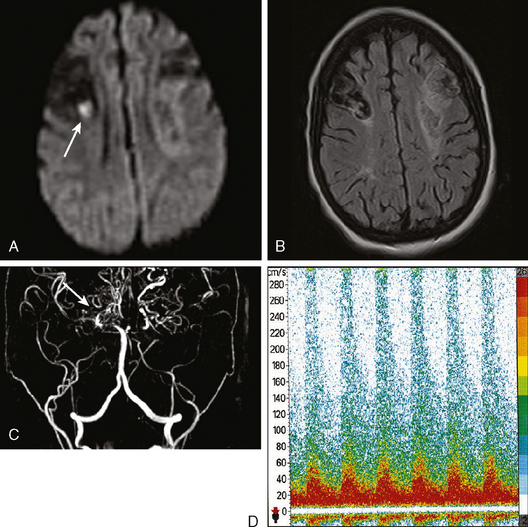

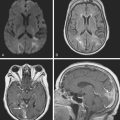

Current neuroimaging techniques have greatly enhanced our ability to diagnose CVT.3,13 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), particularly in combination with MR venography (MRV), provides excellent diagnostic yield in cases of thrombosis of dural sinus or deep cerebral veins (Figure 14-1).13,14 It is worth reemphasizing that noninvasive imaging modalities are allowing us to learn the broad spectrum of CVT. Although once the diagnosis was only suspected after severe intracranial hypertension or venous infarctions had occurred, today the possibility of CVT must be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with new headaches and benign intracranial hypertension. Often CVT can be timely diagnosed only by keeping a low threshold for its clinical suspicion. A delayed or missed diagnosis of CVT, unfortunately still a common occurrence in practice, cannot be justified now that we have reliable and extremely safe means to reach the diagnosis.

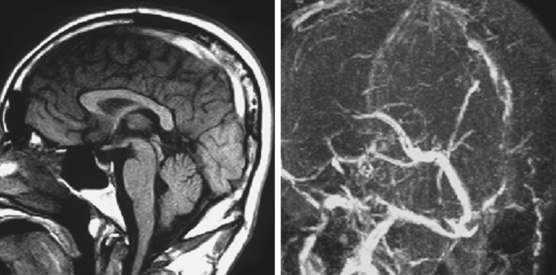

Figure 14-1 Example of normal gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance venography. Refer to Figure 14-3 for anatomical details.

Although MRI/MRV is the most proved and widely used set of tests for the identification of CVT, computed tomography (CT)/CT venogram (CTV) represent a valuable alternative when MRI is contraindicated or unavailable. The main disadvantage of CTV is the requirement for administration of iodinated contrast material.

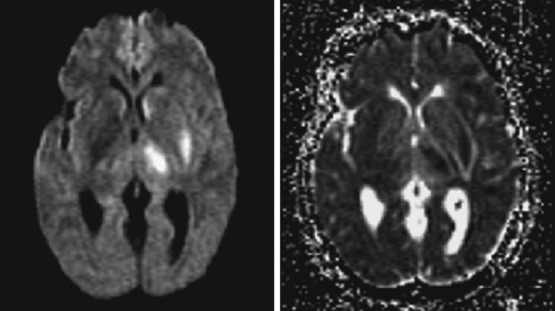

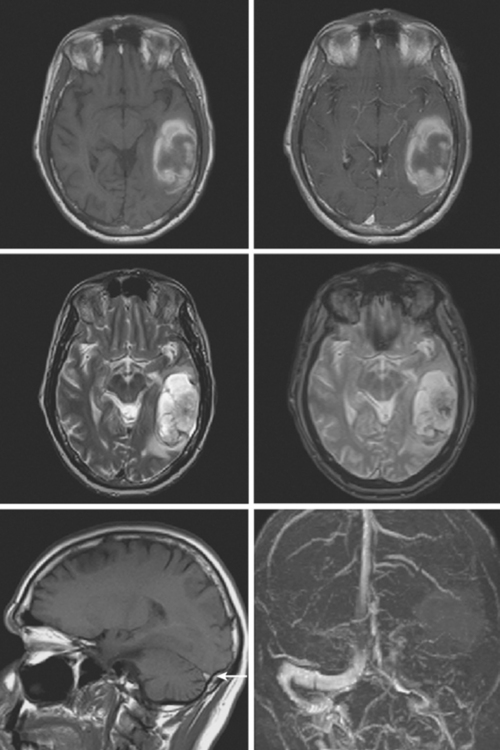

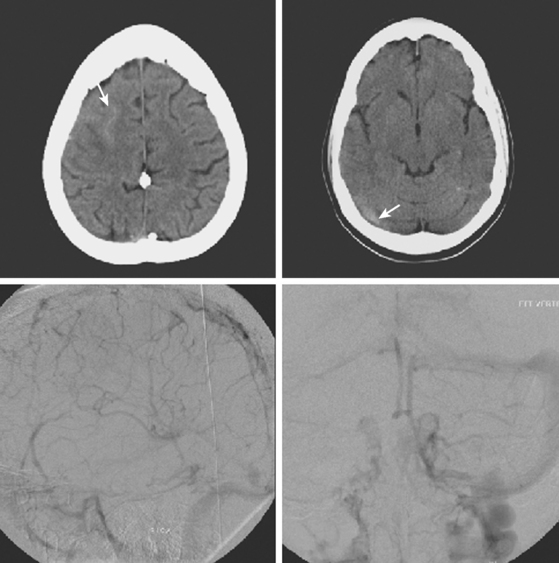

On examination at the hospital, the patient was drowsy, had bilateral papilledema, right VI nerve palsy, and peripheral right facial nerve palsy. Otherwise the examination was unremarkable. She underwent MRI and MRV of the brain that demonstrated extensive thrombosis of the posterior two thirds of the superior sagittal sinus and the proximal transverse sinuses (Figure 14-2). Thrombophilia workup was negative.

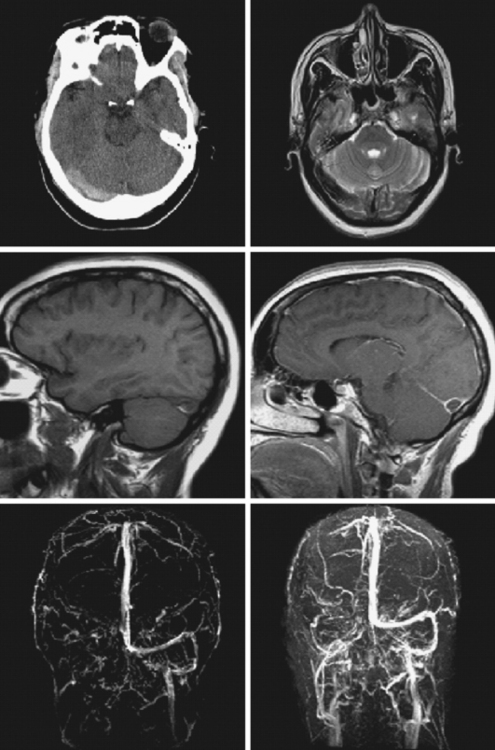

ANATOMY OF THE VENOUS SYSTEM

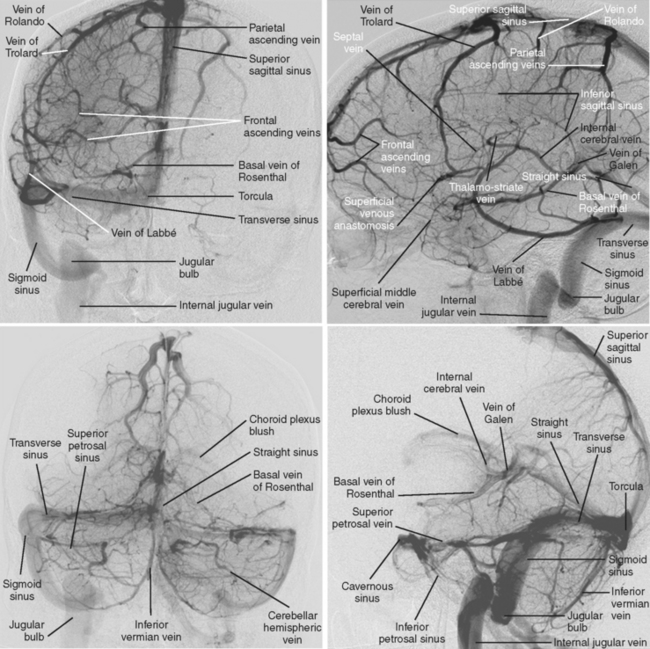

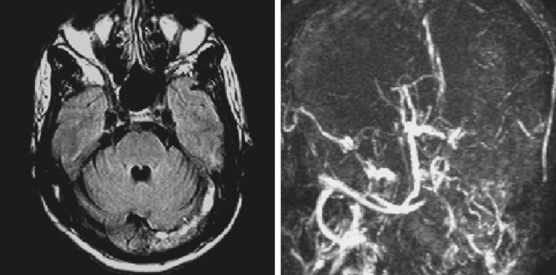

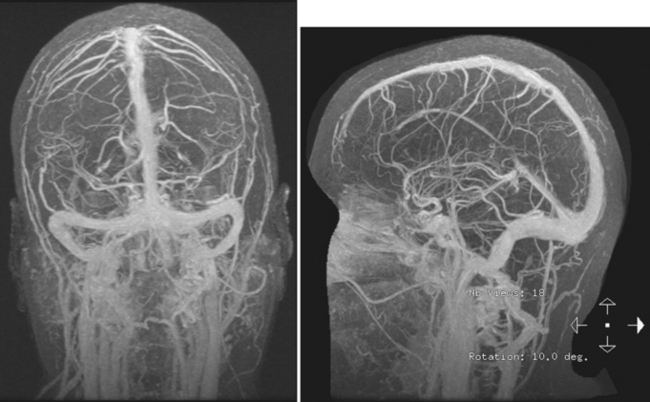

The cerebral venous system consists of dural venous sinuses, superficial veins, and deep veins. The dural venous sinuses are venous channels devoid of valves situated between the two layers of the dura, and thus they are not collapsible. They constitute the major draining pathways of the cerebral venous circulation. Cerebral veins are also devoid of valvular structures and have a very thin wall with no muscular tissue. They empty into the dural sinuses but may reverse their flow in cases of dural sinus occlusion. Venous anatomy is illustrated on angiographic pictures shown in Figure 14-3.

Dural Sinuses

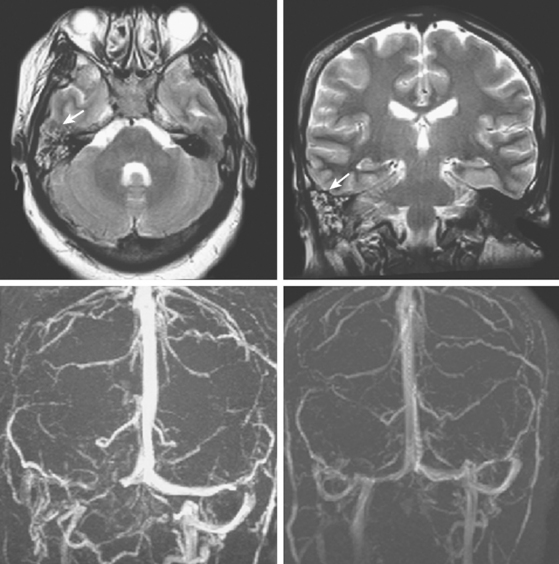

The straight sinus is situated at the line of the junction of the falx cerebri with the tentorium cerebelli. After a descending course, it terminates at the internal occipital protuberance, usually emptying into the left transverse sinus. It receives venous blood flow from the great vein of Galen and superior cerebellar veins, thus participating in the deep venous drainage. Occlusion of this sinus usually produces venous infarcts in the deep basal ganglia.

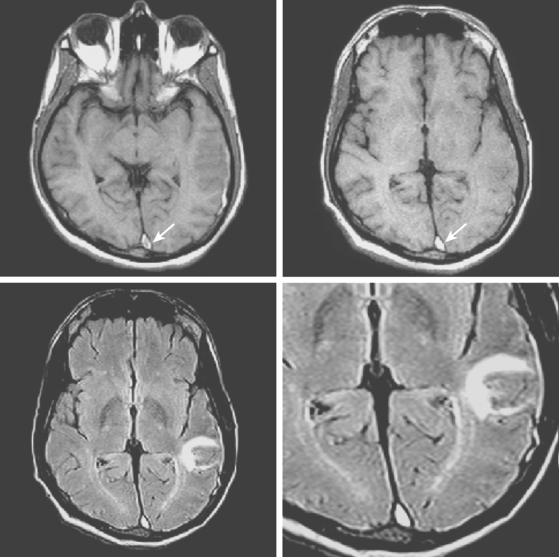

The transverse sinuses are contained within the attachment of the tentorial leaves to the calvarium. At the posterior border of the petrous temporal bone, the transverse sinuses receive the superior petrosal sinus to become the sigmoid sinuses. Transverse sinuses receive blood from the superior sagittal sinus and straight sinus, as well as bridging veins from cerebellum, inferolateral surfaces of the temporal and occipital lobes, and tentorium. It also receives blood from the cortical vein of Labbé. In more than half of cases, the right transverse sinus is larger than the left.15,16 In up to 20% of the cases, a narrowed or atretic segment can be identified in at least one of the transverse sinuses.16

Deep Cerebral Veins

IMAGING CHARACTERISTICS OF CVT

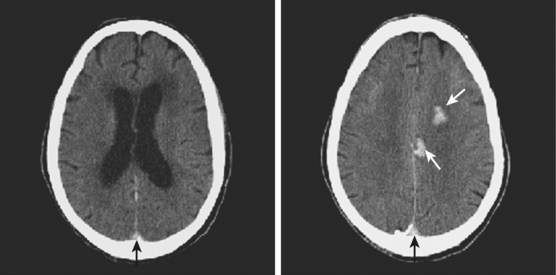

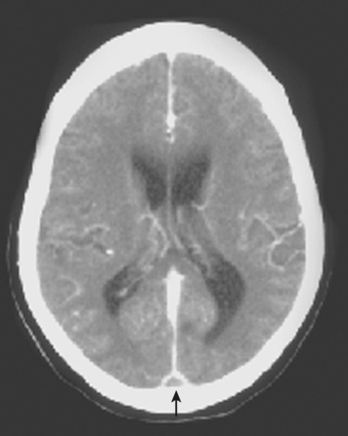

Computed Tomography

Signs of Parenchymal Involvement

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Signs of Parenchymal Involvement

Angiographic, Magnetic Resonance, and Computed Tomography Venograms

SINUS OCCLUSION SYNDROMES

Severe headache often associated with papilledema is the most common presentation of venous sinus thrombosis.3,5 The headache typically worsens for hours to a couple of days before reaching its maximal intensity, but thunderclap headache can also be the first manifestation of CVT.43 Cranial nerve deficits, especially abducens nerve palsy, can be accompanying signs. Complex partial seizures and focal neurological deficits may occur; they usually correlate with parenchymal lesions on brain imaging but sometimes are generated by milder degrees of swelling, which only cause subtle radiological changes. Rapid development of coma may be the presentation of deep venous thrombosis with bilateral thalamic damage.

Several characteristic clinical patterns have been recognized: (1) acute to subacute onset of focal neurological deficits and seizures; (2) isolated intracranial hypertension associated with headaches, papilledema, and unilateral or bilateral VIth nerve palsy; (3) generalized encephalopathy or coma without major focal neurological deficits, a pattern that is more common in deep vein thrombosis; and (4) acute proptosis, chemosis, and painful ophthalmoplegia in cases of cavernous sinus thrombosis.4 However, atypical presentations are not exceptional.3 The onset of clinical manifestations varies substantially; subacute onset (within a month) occurs in about 50% of the cases, acute presentation in 30%, and chronic presentation in 20%.44 Symptoms may progress or fluctuate with extension of the thrombosis, opening of collateral draining channels, and recanalization from endogenous thrombolysis.6

Superior Sagittal Sinus

Transverse Sinus Thrombosis

Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis

Deep Vein Thrombosis

Cortical Vein Thrombosis

Atypical Presentations

MANAGEMENT AND PROGNOSIS

1 Ribes MF. Des recherches faites sur la phlébite. Revue Médicale Française et Etrangère et Journal de Clinique de l’Hôtel-Dieu et de la Charité de Paris. 1825;3:5-41.

2 Stuart EA, O’Brien FH, McNally WJ. Cerebral venous thrombosis. Its occurrence; its localization; its sources and sequelae. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1951;60:406-438.

3 Bousser MG, Ferro JM. Cerebral venous thrombosis: an update. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:162-170.

4 Crassard I, Bousser MG. Cerebral venous thrombosis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2004;24:156-163.

5 Stam J. Thrombosis of the cerebral veins and sinuses. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1791-1798.

6 Masuhr F, Mehraein S, Einhaupl K. Cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis. J Neurol. 2004;251:11-23.

7 Averback P. Primary cerebral venous thrombosis in young adults: the diverse manifestations of an underrecognized disease. Ann Neurol. 1978;3:81-86.

8 Biousse V, Ameri A, Bousser MG. Isolated intracranial hypertension as the only sign of cerebral venous thrombosis. Neurology. 1999;53:1537-1542.

9 Lam BL, Schatz NJ, Glaser JS, Bowen BC. Pseudotumor cerebri from cranial venous obstruction. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:706-712.

10 Gosk-Bierska I, Wysokinski W, Brown RDJr, Karnicki K, Grill D, Wiste H, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: incidence of venous thrombosis recurrence and survival. Neurology. 2006;67:814-819.

11 Cumurciuc R, Crassard I, Sarov M, Valade D, Bousser MG. Headache as the only neurological sign of cerebral venous thrombosis: a series of 17 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1084-1087.

12 Cumurciuc R, Crassard I, Sarov M, Valade D, Bousser MG. Headache as the only neurological sign of cerebral venous thrombosis: a series of 17 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1084-1087.

13 Leach JL, Fortuna RB, Jones BV, Gaskill-Shipley MF. Imaging of cerebral venous thrombosis: current techniques, spectrum of findings, and diagnostic pitfalls. Radiographics. 2006;26(1 Suppl):S19-41. discussion S42–43.

14 Agid R, Shelef I, Scott JN, Farb RI. Imaging of the intracranial venous system. Neurologist. 2008;14:12-22.

15 Widjaja E, Griffiths PD. Intracranial MR venography in children: normal anatomy and variations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:1557-1562.

16 Zouaoui A, Hidden G. Cerebral venous sinuses: anatomical variants or thrombosis? Acta Anat (Basel). 1988;133:318-324.

17 Virapongse C, Cazenave C, Quisling R, Sarwar M, Hunter S. The empty delta sign: frequency and significance in 76 cases of dural sinus thrombosis. Radiology. 1987;162:779-785.

18 Davies RP, Slavotinek JP. Incidence of the empty delta sign in computed tomography in the paediatric age group. Australas Radiol. 1994;38:17-19.

19 Ulmer JL, Elster AD. Physiologic mechanisms underlying the delayed delta sign. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1991;12:647-650.

20 Yuh WT, Simonson TM, Wang AM, Koci TM, Tali ET, Fisher DJ, et al. Venous sinus occlusive disease: MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:309-316.

21 Ferro JM, Canhao P, Stam J, Bousser MG, Barinagarrementeria F. Prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: results of the International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVT). Stroke. 2004;35:664-670.

22 Keiper MD, Ng SE, Atlas SW, Grossman RI. Subcortical hemorrhage: marker for radiographically occult cerebral vein thrombosis on CT. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1995;19:527-531.

23 Bianchi D, Maeder P, Bogousslavsky J, Schnyder P, Meuli RA. Diagnosis of cerebral venous thrombosis with routine magnetic resonance: an update. Eur Neurol. 1998;40:179-190.

24 Isensee C, Reul J, Thron A. Magnetic resonance imaging of thrombosed dural sinuses. Stroke. 1994;25:29-34.

25 Tsai FY, Wang AM, Matovich VB, Lavin M, Berberian B, Simonson TM, et al. MR staging of acute dural sinus thrombosis: correlation with venous pressure measurements and implications for treatment and prognosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:1021-1029.

26 Dormont D, Sag K, Biondi A, Wechsler B, Marsault C. Gadolinium-enhanced MR of chronic dural sinus thrombosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:1347-1352.

27 Idbaih A, Boukobza M, Crassard I, Porcher R, Bousser MG, Chabriat H. MRI of clot in cerebral venous thrombosis: high diagnostic value of susceptibility-weighted images. Stroke. 2006;37:991-995.

28 Selim M, Fink J, Linfante I, Kumar S, Schlaug G, Caplan LR. Diagnosis of cerebral venous thrombosis with echo-planar T2*-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1021-1026.

29 Favrole P, Guichard JP, Crassard I, Bousser MG, Chabriat H. Diffusion-weighted imaging of intravascular clots in cerebral venous thrombosis. Stroke. 2004;35:99-103.

30 Keller E, Flacke S, Urbach H, Schild HH. Diffusion- and perfusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in deep cerebral venous thrombosis. Stroke. 1999;30:1144-1146.

31 Chu K, Kang DW, Yoon BW, Roh JK. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance in cerebral venous thrombosis. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1569-1576.

32 Lovblad KO, Bassetti C, Schneider J, Guzman R, El Koussy M, Remonda L, et al. Diffusion-weighted MR in cerebral venous thrombosis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2001;11:169-176.

33 Mullins ME, Grant PE, Wang B, Gonzalez RG, Schaefer PW. Parenchymal abnormalities associated with cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: assessment with diffusion-weighted MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:1666-1675.

34 Ducreux D, Oppenheim C, Vandamme X, Dormont D, Samson Y, Rancurel G, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging patterns of brain damage associated with cerebral venous thrombosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:261-268.

35 Doege CA, Tavakolian R, Kerskens CM, Romero BI, Lehmann R, Einhaupl KM, et al. Perfusion and diffusion magnetic resonance imaging in human cerebral venous thrombosis. J Neurol. 2001;248:564-571.

36 Ayanzen RH, Bird CR, Keller PJ, McCully FJ, Theobald MR, Heiserman JE. Cerebral MR venography: normal anatomy and potential diagnostic pitfalls. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:74-78.

37 Farb RI, Vanek I, Scott JN, Mikulis DJ, Willinsky RA, Tomlinson G, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: the prevalence and morphology of sinovenous stenosis. Neurology. 2003;60:1418-1424.

38 White JB, Kaufmann TJ, Kallmes DF. Venous sinus thrombosis: a misdiagnosis using MR angiography. Neurocrit Care. 2008;8:290-292.

39 Hu HH, Campeau NG, Huston JIII, Kruger DG, Haider CR, Riederer SJ. High-spatial-resolution contrast-enhanced MR angiography of the intracranial venous system with fourfold accelerated two-dimensional sensitivity encoding. Radiology. 2007;243:681-853.

40 Casey SO, Alberico RA, Patel M, Jimenez JM, Ozsvath RR, Maguire WM, et al. Cerebral CT venography. Radiology. 1996;198:163-170.

41 Khandelwal N, Agarwal A, Kochhar R, Bapuraj JR, Singh P, Prabhakar S, et al. Comparison of CT venography with MR venography in cerebral sinovenous thrombosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:1637-1643.

42 Wasay M, Azeemuddin M. Neuroimaging of cerebral venous thrombosis. J Neuroimaging. 2005;15:118-128.

43 de Bruijn SF, Stam J, Kappelle LJ. Thunderclap headache as first symptom of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. CVST Study Group. Lancet. 1996;348:1623-1625.

44 Bousser MG. Cerebral venous thrombosis: diagnosis and management. J Neurol. 2000;247:252-258.

45 Amran M, Sidek DS, Hamzah M, Abdullah JM, Halim AS, Johari MR, et al. Cavernous sinus thrombosis secondary to sinusitis. J Otolaryngol. 2002;31:165-169.

46 van den Bergh WM, van der Schaaf I, van Gijn J. The spectrum of presentations of venous infarction caused by deep cerebral vein thrombosis. Neurology. 2005;65:192-196.

47 Lafitte F, Boukobza M, Guichard JP, Reizine D, Woimant F, Merland JJ. Deep cerebral venous thrombosis: imaging in eight cases. Neuroradiology. 1999;41:410-418.

48 Jacobs K, Moulin T, Bogousslavsky J, Woimant F, Dehaene I, Tatu L, et al. The stroke syndrome of cortical vein thrombosis. Neurology. 1996;47:376-382.

49 Sagduyu A, Sirin H, Mulayim S, Bademkiran F, Yunten N, Kitis O, et al. Cerebral cortical and deep venous thrombosis without sinus thrombosis: clinical MRI correlates. Acta Neurol Scand. 2006;114:254-260.

50 Canhao P, Ferro JM, Lindgren AG, Bousser MG, Stam J, Barinagarrementeria F. Causes and predictors of death in cerebral venous thrombosis. Stroke. 2005;36:1720-1725.

51 Stam J, de Bruijn S, deVeber G. Anticoagulation for cerebral sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 2003;34:1054-1055.

52 Einhaupl K, Bousser MG, de Bruijn SF, Ferro JM, Martinelli I, Masuhr F, et al. EFNS guideline on the treatment of cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:553-559.

53 Ferro JM, Canhao P. Acute treatment of cerebral venous and dural sinus thrombosis. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2008;10:126-137.

54 Wysokinska EM, Wysokinski WE, Brown RD, Karnicki K, Gosk-Beirska I, Grill D, et al. Thrombophilia differences in cerebral venous sinus and lower extremity deep venous thrombosis. Neurology. 2008;70:627-633.

55 Philips MF, Bagley LJ, Sinson GP, Raps EC, Galetta SL, Zager EL, et al. Endovascular thrombolysis for symptomatic cerebral venous thrombosis. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:65-71.