CHAPTER 46 CEREBRAL VENOUS THROMBOSIS

Cerebral vein and sinus thrombosis (CVST) is a rare event in comparison with arterial stroke, accounting for less than 1% of all strokes. CVST occurs in all age groups, peaking in incidence among neonates and young adults. Clinical diagnosis is difficult, because of the wide spectrum of clinical symptoms of CVST. The achievements of neuroimaging since the 1970s have been fundamental for diagnosing and treating CVST and for a better understanding of its pathogenesis. Early diagnosis of CVST is crucial, because therapy, based mainly on anticoagulation, reduces the risk of fatal outcome and severe disability.1,2

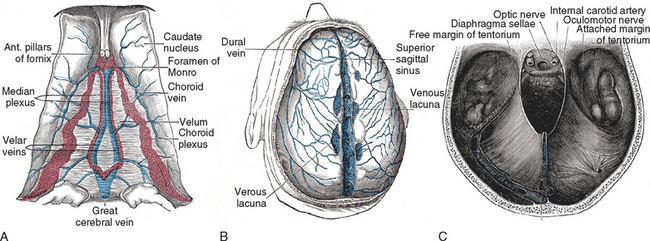

ANATOMY OF THE INTRACRANIAL VENOUS SYSTEM

Cortical Cerebral Veins

Deep Cerebral Veins

Posterior Fossa Veins

The venous drainage of the posterior fossa is highly variable. Four main systems can be outlined:

Dural Sinuses

The dural sinuses are situated between the leaves of the falx and the tentorium and are triangular in section. They drain blood from the cortex, the meninges, and the scalp (through the calvarian veins) and deliver it to the internal jugular veins. They are connected with the extracranial veins in the scalp by the emissary veins. This may explain dural involvement after cutaneous contusions or infections (Fig. 46-1).

Venous Anastomoses

The intracranial venous system has no valves and therefore allows reversals of the blood flow direction, following pressure gradients. The most important vessels of this system are (1) the great anastomotic vein of Trolard that runs from the sylvian fissure to the SSS, thus forming an anastomosis between the SSS and the petrosal sinuses, and (2) the little anastomotic vein of Labbé, which connects the superficial sylvian vein with the transverse sinus or connects the SSS with the transverse sinus (depending on interindividual variability). There are also other, less important links, such as those between the little cortical veins and the adjacent sinuses or those between the basal vein of Rosenthal and the cortical veins. Transcerebral veins are virtual vessels that, when necessary, connect superficial and deep veins, crossing the cerebral parenchyma. The dural sinuses also communicate with the meningeal, diploic, and calvarian veins through the emissary veins.1–5

EPIDEMIOLOGY

CVST may manifest with such a wide spectrum of clinical signs and symptoms that it goes unrecognized in quite a few patients. It follows that epidemiological studies are difficult to perform. On the basis of retrospective trials, CVST accounts for about 0.1% to 9% (mean, about 1%) of all deaths for stroke, with great geographic and ethnic variabilities.1,2,6–8 In industrialized countries, the incidence of CVST is estimated between 1.5 and 2.5 cases per 100,000 per year.6 Although these numbers, based on CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, are remarkably higher than those observed before the neuroimaging era, they still account for only patients who present with the more severe consequences of CVST: namely, hemorrhagic or ischemic venous strokes. As the frequency of venous stroke ranges from 30% to 80% of all cases, the prevalence of patients who develop symptoms related to intracranial hypertension might be considerably higher.6,9–12

In a multicenter prospective observational study, 624 patients with CVST were enrolled. Female gender was prevalent (74.5%); the mean age was 39 years. Patients were predominantly white (79.2% versus 9.3% Hispanic, 5% black, 3.4% Asian, and 3.1% other races). Ischemic venous infarction was present in 46.5% patients, and hemorrhagic lesions were detected in 39.3% patients. Ischemic and hemorrhagic infarcts coexisted in some patients; the cumulative rate of parenchymal lesions at neuroimaging was 62.9%. The SSS was the most frequently involved (62%), followed by the left lateral sinus (44.7%), the right transverse sinus (41.2%), the straight sinus (18%), the choroidal vein (17.1%), and the jugular veins (11.9%). The deep venous system was involved in 10.9% of patients, and the cavernous sinuses in 1.3%. A posterior fossa vein thrombosis was reported in only 0.3%.13

In one study, researchers have investigated the distribution of risk factors and clinical features of CVST among white and African-Brazilian patients. The female/male ratio was higher among the African-Brazilian patients than among the white patients (4.75 versus 1.36), whereas the mean ages were similar. African-Brazilian patients had higher rates of focal deficits (60.8% versus 46.1%) and decreased consciousness (47.8% versus 27%); however, these differences were not significant.7

A high incidence of CVST in young women, especially during pregnancy and the puerperium, has been reported in several studies.6,11,12 As a matter of fact, estimates of CVST associated with pregnancy and the puerperium range from 2 to 60 per 100,000 deliveries in western Europe and North America and from 200 to 500 per 100,000 in India.1,2 The use of oral contraceptives appears to be a risk factor for CVST.1,2,6,10–13

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The causal factors leading to CVST are essentially four: (1) prothrombotic state; (2) venous stasis; (3) direct involvement of the venous wall; and (4) abnormal blood viscosity.14 Symptoms of sinovenous occlusion may arise directly from the primary or underlying process, venous obstruction, vascular inflammation, or secondary complications. Venous obstruction causes a rise of venous and parenchymal pressure in its competence territory, which leads to venous distension and edema. Many of the clinical consequences of CVST arise from brain swelling and increased intracranial pressure caused both by venous engorgement and by decreased cerebrospinal fluid absorption secondary to venous hypertension. Furthermore, in the majority of cases, thrombosis involves multiple dural sinuses or both sinuses and veins.1,2,13,15

Experimental studies have contributed to a better definition of the pathological features of CVST. A subacute occlusion of SSS provokes clinical manifestations only when the occlusion spreads to cortical or bridging veins.16–20 SSS occlusion is usually associated with brain swelling, an increase in intracranial pressure, and diffuse cellular damage.16–21 On the other hand, occlusion of bridging and cortical veins produces a localized well-shaped venous infarction, with both ischemic and hemorrhagic features, surrounded by brain swelling and edema.19–23 In cats, the ligature of SSS provokes a stroke only when located after the confluence between this sinus and the rolandic vein, because the anterior third of the sinus is well compensated by collateral vessels. What is remarkable is that ischemic/hemorrhagic lesions are absent at 2 hours but present at 24 hours; this demonstrates that the acute occlusion of a dural sinus, at least in experimental conditions, is related not to an acute infarction but only to a subacute one.19 This observation could also apply to humans, inasmuch as the majority of patients with dural sinus involvement exhibit a subacute onset of the CVST signs and symptoms. Also remarkable is that neither the site nor the extent of a sinus occlusion is indicative of the final site and size of the corresponding ischemic lesion. On the contrary: The thrombosis of a cortical vein produces a definite area of infarction in the gray and superficial white matter. As a consequence, patients with cortical and deep vein thrombosis show the worst clinical outcome,22 because the deep vein thrombosis produces a widespread lesion that involves the thalamus, the deep white matter, and the upper parts of the brainstem.1,2,24

DIAGNOSIS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Headache is the most frequent presenting symptom and the most common complaint (75% of cases).1,2,12,25 The headache is usually diffuse and progressive, with no typical clinical characteristics or temporal profile. In the 2004 International Classification of Headache Syndromes, headache associated with CVST is classified as follows: (1) any new headache, with or without neurological signs, that fulfills the second and third criteria; (2) headache with neuroimaging evidence of CVST; (3) headache (and neurological signs, if present) that develops in close temporal relation to CVST.26

Intracranial Hypertension Syndrome

Headache is the most common clinical symptom of IHS, reported in 75% to 95% of patients.6 It represents the inaugural symptom in 70% to 75% of cases and is often the unique clinical manifestation of IHS.6–27 The headache may be any grade of severity, diffuse or localized, and persistent or intermittent. The onset is usually subacute (2 to 30 days) but can also be acute (>2 days) or chronic (>30 days).1,2 Attacks may mimic migraine or may be interpreted as a subarachnoid hemorrhage manifesting as a thunderclap-type headache, with instantaneous onset and coming on very quickly.27 Papilledema is observed in about 50% of affected patients.11 Only 20% to 40% of patients have the complete syndrome of isolated IHS with headache, nausea, vomiting, papilledema, transient visual obscurations, and eventually cranial nerve VI palsy. The involvement of other cranial nerves is very rare.6 IHS resulting from CVST should be differentiated by the idiopathic intracranial hypertension or pseudotumor cerebri, with a complete neuroradiological workup. IHS is more frequently caused by the occlusion of the dural sinuses, particularly the SSS.1,2,27

Stroke-Related Syndrome

This syndrome is typically related to the occurrence of a venous infarction that can be both ischemic and hemorrhagic. In the majority of cases, the pattern is represented by multiple small intraparenchymal hemorrhages, surrounded either by normal parenchyma or by ischemic areas. Its clinical features are ill-defined and differ from those of an arterial stroke, which is more sharply outlined and wedge-shaped. The abundance of collateral vessels and anastomosis of the venous circulation, in comparison with the arterial circulation, is responsible for the lack of topographic localization of the lesions. Focal neurological signs (sensory and motor deficits, speech disturbances, hemianopia) are present in 40% to 60% of all cases.6 Headache, vomiting, and ataxia with acute onset are the most frequent symptoms in patients with cerebellar vein thrombosis, which is always associated with a concomitant effect on the lateral sagittal sinus and SSS.6

Encephalopathic Syndrome

This condition is the least frequent manifestation of CVST but also the most severe. It is typically related to the involvement of the deep venous system, with diffuse damage of the white matter, basal ganglia, thalamus, and mesencephalon. Parenchymal damage may be related to necrosis, hemorrhages, and brain swelling.1,2,28 The clinical syndrome is characterized by generalized seizures, psychiatric disturbances, confusion, and variable levels of consciousness, disorders of which range from stupor to coma.1,2,6,10,11,25 Major cognitive impairments are reported in only 15% to 19% of cases.6

Focal or generalized seizures are present in more than 40% of patients with CVST2 and may occur in every related clinical syndrome. During the puerperium, the incidence is even higher (76%).6,12 Among the focal forms, the jacksonian type is the most common and is characteristically associated with Todd’s postconvulsive paresis, which is rare in idiopathic epilepsy.6,12,29 Nonetheless, only a few cases progress to epilepsy.29

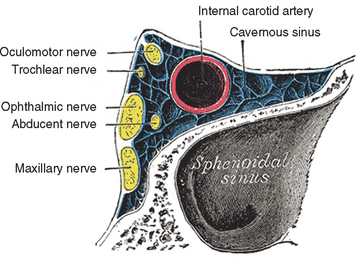

Cavernous sinus thrombosis provokes a peculiar neurological syndrome characterized by any combination of unilateral chemosis, proptosis, and eyelid edema (caused by inadequate ocular venous drainage from the ophthalmic vein), with diplopia resulting from the involvement of the oculomotor nerves. Myosis and ptosis may also be present as a result of involvement of the third cranial nerve, as may mydriasis, caused by the involvement of the pericarotic sympathetic plexus. Retro-orbital and/or frontotemporal pain and anesthesia in the territories of the first and second branches of the trigeminus may also be present, constituting the so-called painful ophthalmoplegia. In the case of slow occlusion of the sinus, the only clinical manifestation may be limited to the sixth nerve palsy accompanied with pain. The thrombosis may extend to the contralateral sinuses. The differential diagnosis should take into consideration other causes of painful ophthalmoplegia such as the Tolosa-Hunt syndrome, which is an idiopathic granulomatous inflammation of the dural wall of the cavernous sinuses; giant cells arteritis; sarcoidosis; local or general neoplasm; pseudotumor orbitae; and infectious thrombophlebitis caused by the propagation of a septic process from the face or neck into the cavernous sinuses.30

DIAGNOSTIC METHODS

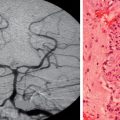

Venous angiography was the first instrumental technique used to diagnose CVST. Today, its clinical use is limited to dubious cases because of its excellent sensitivity. Angiography shows venous thrombosis as an interruption of flow that may be differentiated by sinus aplasia by the presence of a tortuous collateral circulation, consisting of “corkscrew vessels.”1,2 These vessels cannot be visualized by any other technique, and thus angiography remains the most important diagnostic tool in these cases.31

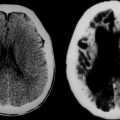

CT scan is usually the first investigation performed in the emergency department6; thus, it plays an important role in differential diagnosis, allowing the clinician to rule out disorders that may mimic CVST, such as tumors, encephalitis, brain abscesses, and subarachnoid hemorrhage.32 However, CT scans may be normal in 25% to 30% of patients.6

On CT scan, CVST may show direct and indirect signs. Direct signs are as follows:

Since 2000, new CT techniques have improved the diagnostic sensitivity in detecting CVST. In particular, helical CT venography has improved the sensitivity of computed tomography to 95%,35 demonstrating an even higher sensitivity than digital subtraction angiography of the venous phase used to visualize thrombosis in cavernous sinuses and ISS. Multislice CT angiography is frequently available in the emergency department, and it is useful to differentiate arterial from venous infarction.36

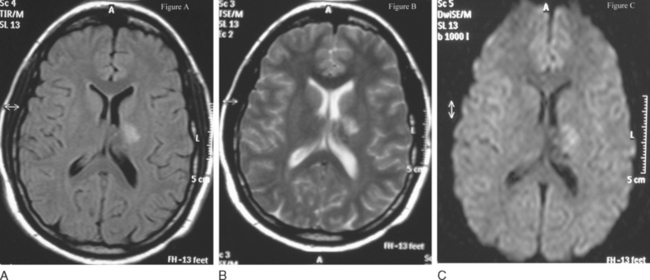

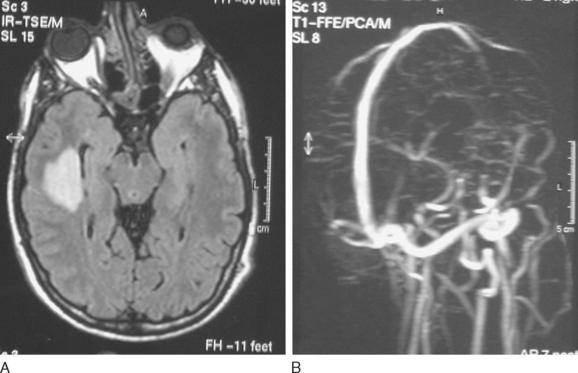

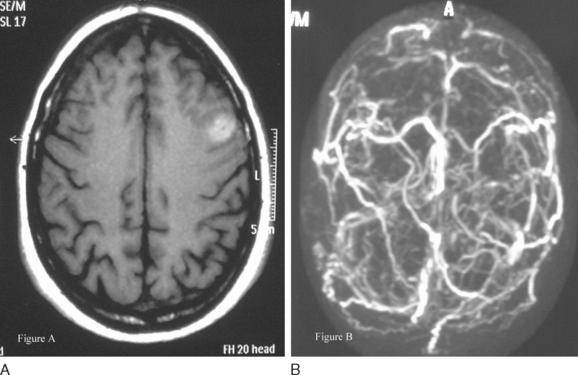

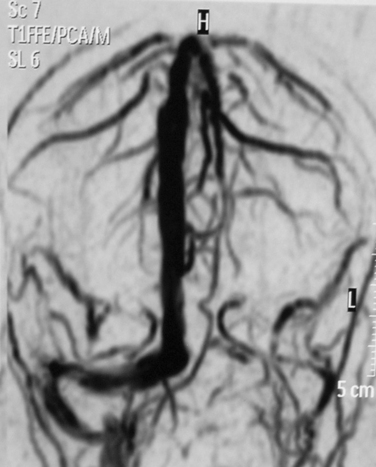

Nowadays, MRI is the “gold standard” for diagnosing CVST. The signal characteristics of venous thrombi evolve in several stages. In the first days, the thrombus is isointense on T1-weighted sequences and hypointense on T2-weighted sequences. If the posterior part of the SSS is involved, a dural wall hyperintensity, similar to the CT delta sign, is visible after gadolinium injection. Afterward, the clot becomes hyperintense, first in T1-weighted sequences and later also in T2-weighted sequences, with a characteristic progression of the hyperintensity from the periphery to the center. This phenomenon results from the transformation of hemoglobin into methemoglobin.6,11,24 After the first month, the hyperintensity disappears, first in T1- and then in T2-weighted sequences; therefore, the persistent occlusion can be visible, as an isointense signal, only in flow-sensitive gadolinium-enhanced sequences.1,2,6,11,24 Venous infarction on MRI appears as multiple areas of hyperintensity mixed with isointense or hypointense areas.6,24 Magnetic resonance venous angiography is an excellent tool for diagnosing the sharp interruption of a dural sinus; however, its capability to diagnose thrombosis of specific cortical veins is still weak, because of the individual variability and complexity of the cerebral venous system. Resolution and sensitivity are increased with the phase-contrast technique in regard to the time-of-flight technique.6

Magnetic resonance venous angiography is also useful for studying the hypoplasia of intracranial sinuses, an important source of pitfalls in the diagnosis of CVST.37

A promising technique is the gadolinium-enhanced auto-triggered elliptical centric-ordered magnetic resonance venography, which produces three-dimensional and digitally amplified images and is more sensitive than the classic gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance venography.38

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) has demonstrated high sensitivity in detecting ischemic strokes in their initial phase. In CVST, DWI may be used to diagnose a venous infarction in the earlier hours, when it is more likely to be ameliorated with adequate medical intervention.6,24 It demonstrates the coexistence in the venous infarction of cytotoxic and vasogenic edema24,39,40 (Fig. 46-3). Another possible application of DWI may be to detect early recanalization, as demonstrated by Bousser and coworkers. Twenty-eight patients with recent CVST were studied with DWI in the acute phase, in order to identify hyperintense signals in the sinuses that corresponded to the thrombus. DWI hyperintense signals in the sinuses were detected in 12 of the 28 patients (43%) corresponding to 20 occluded veins or sinus. Two or three months after the beginning of anticoagulant administration, this phenomenon significantly decreased (35% versus 88%; P = 0.05) probably because of the different molecular structure of the clot.41

Since 2000, some advances have been made in testing possible applications of transcranial Doppler (TCD) imaging in CVST. In patients with CVST, higher values of peak systolic, end-diastolic, and mean blood flow velocities have been reported in the deep venous system than in controls.42,43 However, although blood flow alterations in patients with CVST are more frequent than in controls, the sensitivity of TCD imaging is lower than that of MRI.43,44 Interestingly, patients with CVST showed a decrease in velocity values after starting heparin therapy, with a rebound of velocity values immediately after heparin suspension. Higher velocities in the acute phase were significantly associated with disturbances of consciousness. No relation was found between increased flow velocities and disease onset, severity of motor deficits, and presence of bleeding. In addition, the initial blood flow velocity was not predictive of stroke outcome.44

The Doppler technique is also useful in patients with CVST in detecting microembolic signals in the internal jugular vein, which are higher than in controls.46 Echocontrast techniques have been applied in order to increase TCD resolution.47

RISK FACTORS

Several conditions have been found to be associated with CVST, but only few of them produce an effective increase of the relative risk. The most common risk factors for CVST are listed in Table 46-1. Idiopathic cases account for 25% to 30% of cases of CVST.1,2,10,11,25

TABLE 46-1 Risk Factors for Cerebral Vein and Sinus Thrombosis

| Septic thrombosis | Bacterial (including syphilis), fungal (Mucor, Aspergillus, Rhizopus), viral (HIV, herpes zoster) and parasitic (Trichinella) infections |

| Head injuries | Penetrating and nonpenetrating head injuries, surgery, intravascular foreign bodies, iopamidol myelography |

| Hematological disorders | Polycythemia vera, altitude-induced polycythemia, sickle cell anemia, cryofibrinogenemia, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, thrombocytosis, multiple myeloma, severe anemia |

| Thrombophilic disorders | Antithrombin III deficiency, protein C and/or protein S deficiency, activated protein C resistance, G20210A prothrombin mutation, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation, MTHFR mutation, hyperhomocysteinemia, factor V Leiden, transfusion reaction, nephrotic syndrome |

| Metabolic disorders | Homocystinuria, carbon monoxide, diabetes, thyroid disorders, hypertriglyceridemia |

| Neoplasia | Metastatic (usually hematogenous malignancies), nonmetastatic complications, meningioma |

| Inflammatory states | Behçet’s syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease), Wegener’s granulomatosis, Cogan’s syndrome, Köhlmeier-Degos disease, polyarteritis nodosa, systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, thromboangiitis obliterans, rheumatoid arthritis |

| Phakomatoses | Sturge-Weber syndrome |

| Hormonal | Pregnancy and puerperium, thyrotoxicosis |

| Vascular disorders | Arteriovenous malformations, arterial occlusions, jugular catheter occlusion, dural fistula |

| Medications | Androgens, oral contraceptives, progestogens, L-asparaginase, pentosan, hormone replacement therapy, cocaine |

| Others | Dehydration, fever, cardiac decompensation, skull abnormalities (achondroplasia, craniometaphyseal dysplasia), lumbar puncture, epidural anesthesia, CSF hypotension |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MTHFR, methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase.

Etiological factors may be divided into two main categories: septic CVST, which accounts for 5% to 15% of the cases, and aseptic CVST, which is predominant in industrialized countries. There are local and general causes for CVST. Local causes are related to head and neck infections (10.3%), tumors (2.2%), head injuries (1.1%), and neurosurgery (0.6%)13,48 (Fig. 46-4). Lumbar puncture, particularly with an intrarachidian injection of drugs (1.9%), may also produce CVST.49,50 In women, the most frequent general causes are pregnancy, puerperium, use of oral anticoagulants, and hormone replacement therapy. All these conditions are associated with high estrogen levels13,51–53 (Fig. 46-5). In the absence of thrombophilias, recurrence of CVST during another pregnancy is very rare.54 On the other hand, recurrences are very frequent in cases of puerperal CVST, which carry the greatest day-by-day risk of development of a vein thrombosis.6 Thus, anticoagulation is recommended in all patients with previous puerperal thrombosis.55 Thrombophilias, both hereditary and acquired, are reported in 20% to 50% of patients with CVST.13 In a series of 121 patients with CVST, prothrombin G20210A was present in 21.5% of patients, factor V Leyden in 12.4%, protein C deficiency in 5.2%, protein S deficiency in 3.1%, and antithrombin III deficiency in 2.5%.56 The presence of prothrombin G20210A and factor V Leyden increased the odds of developing CVST even in the heterozygous form by acting as cofactors with other conditions.56 Less common genetic thrombophilias such as hyperfibrinogenemia, alteration in the plasmin cascade,57 and hyperhomocysteinemia are associated with an increased risk of developing CVST.56,58 Hyperhomocysteinemia may provoke CVST, inducing endothelial toxicity, which is higher for the cerebral vascular system,59,60 and interferes with the clotting cascade.60,61 In the International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVT), the rate of with hyperhomocysteinemia in the whole population was 4.5%, reaching 27% in the series specifically dedicated to estimate the incidence and the risk of CVST associated with thrombophilic disorders.13 Acquired thrombophilic disorders accounted for 6.5% of patients: 5.9% were referable to antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and 0.6% to nephrotic syndrome.13

Another important category of risk factors for CVST is represented by systemic inflammatory disorders, especially if associated with vasculitis. In the ISCVT, systemic lupus erythematosus was found in 1% of patients, Behçet’s disease in 1%, rheumatoid arthritis in 0.2%, thromboangiitis obliterans in 0.2%, inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease) in 1.6%, and sarcoidosis in 0.2%13 (Fig. 46-6).

Systemic infections are reported in 4.3% of patients; cultures and sensitivities are necessary to determine treatment. More diffuse in the past and related to very poor hygienic conditions and the absence of antibiotics, they remain an important cause of CVST and deep vein thrombosis in less industrialized countries. Systemic infections may be an important cause of thrombosis in neonates and young children. These patients are also very frequently at risk for anemia with CVST.62,63 Aseptic cerebral venous thrombosis is also reported in association with tuberculosis.64

TREATMENT

Treatment of the Thrombotic Process

Among the causal treatments, anticoagulants are the more widely used. They are expected not to eliminate an already formed thrombus but to prevent extension of thrombosis to other venous channels. Nonetheless, the use of anticoagulants in patients with CVST is still debated.65–69 The main argument against anticoagulation is the risk of a major hemorrhage in the venous infarct, which is often already a hemorrhagic infarct. Several retrospective trials have shown a potential benefit of anticoagulation in patients with CVST.65,68 To date, however, findings from only two randomized placebo-controlled trials of anticoagulation in CVST are available. The first case-control study involved dose-adjusted intravenous heparin and was prematurely discontinued because of a statistically significant difference in favor of treated patients over controls.67 This was the first study demonstrating that the benefits of intravenous heparin also apply to patients with intracranial hypertension. Furthermore, no additional intracranial hypertension was detected during heparin treatment. In the European double-blind, controlled multicenter trial, weight-adjusted subcutaneous nadroparin for 3 weeks, followed by oral anticoagulation for 3 months, was compared with placebo in 60 patients with CVST. After 3 weeks, a poor outcome (defined as a Barthel Index <15) was observed in 20% of patients receiving nadroparin, in comparison with 24% of the controls. At 12 weeks, a poor outcome was observed in 10% of patients receiving nadroparin, in contrast to 21% of the controls. A complete recovery was observed in 12% of patients receiving nadroparin and 28% of the controls. None of these differences was statistically significant.70 A meta-analysis of the two reported trials showed an absolute risk reduction of 14% in mortality and 15% in mortality and dependency combined in patients undergoing anticoagulation.69 These results, although not statistically significant, are encouraging and strongly endorse, in our opinion, the use of anticoagulants in CVST irrespective of the presence of intracranial hypertension.69,71,72 Anticoagulant treatment should be continued orally for a period of at least 3 to 6 months. In case of puerperium, it should be prolonged for 12 months.73 If prothrombotic risk factors are present, longterm treatment is mandatory.6,73 Of importance is that during pregnancy, particularly in the first 3 months, vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin should be avoided, because they are linked with an increased rate of malformations.73 The first therapeutic choice in this case is therefore low-molecular-weight heparin.6

The use of thrombolytic agents in CVST has been evaluated.65,74–88 Thrombolytic therapy aims at rapid recanalization of the occluded vessel, including, in our case, the cortical veins.71,72 The efficacy and safety of this treatment are debated.74–88

Two different thrombolytic agents have been used in CVST. Urokinase was compared with intravenous heparin in SSS thrombosis. It was fairly well tolerated and more effective than heparin.74–77,83,85,88 The intrathrombus combination of recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rtPA) and intravenous heparin was compared with intravenous heparin alone in patients with sinuses thrombosis. Both treatments were effective and safe, although the outcome was worse in patients with major hemorrhages treated with rtPA.79,82

A retrospective meta-analysis (72 studies, 169 patients enrolled) demonstrated that thrombolytic treatment is associated with a better outcome and is sufficiently safe.83 Nevertheless, to date there is no proof that thrombolytic therapy is better than anticoagulation in patients with CVST. Therefore, it should be used as second choice of therapy in patients whose condition worsens in spite of correct anticoagulation.76,84,89

The use of antiaggregates in patients with acute CVST has been poorly investigated. Experimental studies revealed a better neurological outcome and a higher rate of recanalization with rtPA in combination with the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa direct inhibitor abciximab, in comparison with the association of rtPA with enoxaparine.90 So far, clinical studies investigating the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa direct inhibitors in CVST have never been performed.

There is little information concerning the use of mechanical treatments, such as rheolytic catheter thrombectomy or angioplasty in CVST, and further evidence of their efficacy is needed.91–99 A great limitation of these techniques is represented by the inaccessibility to some intracranial vessels, particularly cortical, bridging, and deep veins, because of their size in comparison with the caliber of the catheter.91–93

Open surgical thrombectomy, combined with local infusion of rtPA, showed a good outcome when used in patients with severe dural sinus thrombosis and deterioration despite anticoagulation. All patients returned to normal activities after surgical treatment.100,101

Symptomatic Treatment

The prophylactic use of anticonvulsants in patients with CVST is still controversial because of their negative effects on brain metabolism and on the level of consciousness. The general attitude, and our advice, is to use these drugs only in patients with seizures.1,2,6,25,29 Focal neurological deficits, cerebral edema, and infarction (especially hemorrhagic) observed on neuroimaging seem to be significant predictors of seizure in patients with CVST.29 A prophylactic treatment with anticonvulsants might be justified in these patients.

Treatment of increased intracranial pressure caused by brain swelling is based on the use of mannitol, seldom in association with other diuretics such as acetazolamide or furosemide. Steroids are not indicated, because of their antifibrinolytic activity (although there are no clinical trials demonstrating a worse outcome in CVST patients treated with steroids).1,2,6,11,25 Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane, which decreases intracranial pressure by alkalotic vasoconstriction, could be used in ventilated patients.6

PROGNOSIS

CVST was long thought to be a rare disease with a poor prognosis.1,2,9–11 Since the mid-1970s, neuroimaging has produced a better understanding of this disease, and the use of anticoagulant therapy has increased the number of good outcomes. In the ISCVT study, after a 16-month median follow-up period, 13.4% of the patients had a modified Rankin scale score of more than 2, and 8.3% had died. Multivariate predictors of death or dependence were central nervous system infections (HR = 3.3%), cancer (HR = 2.9), deep venous system involvement (HR = 2.9), coma (HR = 2.7), age older than 37 years (HR = 2), mental status disorders (HR = 2), hemorrhage visible on CT scan (HR = 1.9), and male gender (HR = 1.6). Only 2.2% of the patients had a recurrent sinus thrombosis, and 4.3% had other thrombotic events.13

The rate of recurrences in patients with CVST ranges from 0% to 11.7%,102 and it is most common in the first year after the previous thrombosis.6,102 The mortality rate ranges between 6% and 33%, and it is higher in septic CVST.11 In one study, researchers investigated the variables influencing the delay between the onset of symptoms and hospital admission for patients with CVST. Twenty-two percent of patients were admitted within 24 hours and 75% within 13 days. In multiple logistic regression analysis, admission within 24 hours was associated positively with mental status disorders (delirium/abulia) and negatively with headache. Intracranial hypertension was associated with an admission delay of more than 4 days, and papilledema, with a delay of more than 13 days. Mean delay between onset and hospital admission was 4 days. Not surprisingly, anticoagulation was started earlier in patients with a more precocious diagnosis, but the proportion of patients treated was not influenced by the delay of admission. Headache was the most common presenting symptom; therefore, CVST should be considered in patients with a new-onset headache or an important change in the clinical features of a preexisting one.11,27

A number of researchers investigated the relationship between delay of anticoagulant treatments and CVST prognosis.103–105 So far, there is no evidence that delay in admission (and diagnosis) might influence CVST prognosis. Female gender, pregnancy, and puerperium, all related to high estrogens levels, seem to be predictive of a good outcome.6,106 Early recanalization, which is a common phenomenon on neuroimaging, has no influence on outcome.107

CONCLUSION

Canhao P, Batista P, Falcao F. Lumbar puncture and dural sinus thrombosis: a causal or casual association? Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;19:53-56.

Camargo EC, Massaro AR, Bacheschi LA, et al. Ethnic differences in cerebral venous thrombosis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;19:147-151.

Ferro JM, Lopes MG, Rosas MJ, et al. Delay in hospital admission of patients with cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;19:152-156.

Rottger C, Madlener K, Heil M, et al. Is heparin treatment the optimal management for cerebral venous thrombosis? Effect of abciximab, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator, and enoxaparin in experimentally induced superior sagittal sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 2005;36:841-846.

Stolz E, Rahimi A, Gerriets T, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis: an all or nothing disease? Prognostic factors and longterm outcome. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2005;107:99-107.

1 Ginsberg MD, Bogousslavsky J. Cerebrovascular Diseases. vol 2. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science; 1998.

2 Bogousslavsky J, Caplan L. Stroke Syndromes. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

3 Williams PL, Warwick R. 37th ed. Gray’s Anatomy. vol 2. Essex, UK: Longman Group; 1989.

4 Mazzocchi G, Nussdorfer G. Anatomia Funzionale del Sistema Nervoso. Padua, Italy: Libreria Cortina, 1993.

5 Netter FH. Atlante di Anatomia Umana [Italian ed]. Origgio, Italy: Ciba-Geigy, 1990.

6 Masuhr F, Mehraein S, Einhaupl K. Cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis. J Neurol. 2004;251:11-23.

7 Camargo EC, Massaro AR, Bacheschi LA, et al. Ethnic differences in cerebral venous thrombosis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;19:147-151.

8 Liu HS, Kho BC, Chan JC, et al. Venous thromboembolism in the Chinese population: experience in a regional hospital in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2002;8:400-405.

9 Stolz E, Rahimi A, Gerriets T, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis: an all or nothing disease? Prognostic factors and longterm outcome. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2005;107:99-107.

10 Bousser MG, Ross Russel R. Cerebral Venous Thrombosis. vol 1. London: WB Saunders; 1997.

11 Crassard I, Bousser MG. Cerebral venous thrombosis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2004;24:156-163.

12 Ameri A, Bousser MG. Cerebral venous thrombosis. Neurol Clin. 1992;10:87-111.

13 Ferro JM, Canhao P, Stam J, et al. Prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: results of the International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVT). Stroke. 2004;35:664-670.

14 Lowe GD. Virchow’s triad revisited: abnormal flow. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2003/2004;33(5–6):455-457.

15 Gettelfinger DM, Kokmen E. Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis. Arch Neurol. 1977;34:2-6.

16 Gotoh M, Ohmoto T, Kuyama H. Experimental study of venous circulatory disturbance by dural sinus occlusion. Acta Neurochir. 1993;124:120-126.

17 Tychmanowicz K, Czernicki Z, Czosnyka M, et al. Early patho-morphological changes and intracranial volume-pressure: relations following the experimental sagittal sinus occlusion. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1990;51:233-235.

18 Tuzgen S, Canbaz B, Kaya AH, et al. Experimental study of rapid versus slow sagittal sinus occlusion in dogs. Neurol India. 2003;51:482-486.

19 Schaller B, Graf R, Wienhard K, et al. A new animal model of cerebral venous infarction: ligation of the posterior part of the superior sagittal sinus in the cat. Swiss Med Wkly. 2003;133(29–30):412-418.

20 Cervos-Navarro J, Kannuki S, Matsumoto K. Neuropathological changes following occlusion of the superior sagittal sinus and cerebral veins in the cat. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1994;20:122-129.

21 Vosko MR, Rother J, Friedl B, et al. Microvascular damage following experimental sinus-vein thrombosis in rats. Acta Neuropathol. 2003;106:501-505.

22 Fries G, Wallenfang T, Hennen J, et al. Occlusion of the pig superior sagittal sinus, bridging and cortical veins: multistep evolution of sinus-vein thrombosis. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:127-133.

23 Bergui M, Bradac GB, Daniele D. Brain lesions due to cerebral venous thrombosis do not correlate with sinus involvement. Neuroradiology. 1999;41:419-424.

24 Haage P, Krings T, Schmitz-Rode T. Nontraumatic vascular emergencies: imaging and intervention in acute venous occlusion. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:2627-2643.

25 Loeb C, Favale E. Neurologia di Fazio-Loeb, 3rd ed. Rome: Casa Editrice Universo, 2003.

26 Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd ed. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(Suppl 1):1160.

27 Iurlaro S, Beghi E, Massetto N, et al. Does headache represent a clinical marker in early diagnosis of cerebral venous thrombosis? A prospective multicentric study. Neurol Sci. 2004;25(Suppl 3):S298-S299.

28 Madan A, Sluzewski M, van Rooij WJ, et al. Thrombosis of the deep cerebral veins: CT and MRI findings with pathologic correlation. Neuroradiology. 1997;39:777-780.

29 Ferro JM, Correia M, Rosas MJ, et al. Seizures in cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;15:78-83.

30 Lenzi GL, Fieschi C. Superior orbital fissure syndrome: review of 130 cases. Eur Neurol. 1977;16:23-30.

31 Wetzel SG, Kirsch E, Stock KW, et al. Cerebral veins: comparative study of CT venography with intraarterial digital subtraction angiography. Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:249-255.

32 Giraud P, Thobois S, Hermier M, et al. Intravenous hypertrophic Pacchioni granulations: differentiation from venous dural thrombosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70:700-701.

33 Deus-Silva L, Voetsch B, Nucci A, et al. An unusual “empty delta sign.”. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1287.

34 Chang R, Friedman DP. Isolated cortical venous thrombosis presenting as subarachnoid hemorrhage: a report of three cases. Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:1676-1679.

35 Casey SO, Alberico RA, Patel M, et al. Cerebral CT venography. Radiology. 1996;198:163-170.

36 Klingebiel R, Busch M, Bohner G, et al. Multislice CT angiography in the evaluation of patients with acute cerebrovascular disease: a promising new diagnostic tool. J Neurol. 2002;249:43-49.

37 Alper F, Kantarci M, Dane S, et al. Importance of anatomical asymmetries of transverse sinuses: an MR venographic study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;18:236-239.

38 Farb RI, Scott JN, Willinsky RA, et al. Intracranial venous system: gadolinium-enhanced three-dimensional MR venography with auto-triggered elliptic centric-ordered sequence—initial experience. Radiology. 2003;226:203-209.

39 Lovblad KO, Bassetti C, Schneider J, et al. Diffusion-weighted MRI suggests the coexistence of cytotoxic and vasogenic oedema in a case of deep cerebral venous thrombosis. Neuroradiology. 2000;42:728-731.

40 Keller E, Flacke S, Urbach H, et al. Diffusion- and perfusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in deep cerebral venous thrombosis. Stroke. 1999;30:1144-1146.

41 Favrole P, Guichard JP, Crassard I, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging of intravascular clots in cerebral venous thrombosis. Stroke. 2004;35:99-103.

42 Schreiber SJ, Stolz E, Valdueza JM. Transcranial ultrasonography of cerebral veins and sinuses. Eur J Ultrasound. 2002;16:59-72.

43 Canhao P, Batista P, Ferro JM. Venous transcranial Doppler in acute dural sinus thrombosis. J Neurol. 1998;245:276-279.

44 Valdueza JM, Hoffmann O, Weih M, et al. Monitoring of venous hemodynamics in patients with cerebral venous thrombosis by transcranial Doppler ultrasound. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:229-234.

45 Stolz E, Gerriets T, Bodeker RH, et al. Intracranial venous hemodynamics is a factor related to a favorable outcome in cerebral venous thrombosis. Stroke. 2002;33:1645-1650.

46 Valdueza JM, Harms L, Doepp F, et al. Venous microembolic signals detected in patients with cerebral sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 1997;28:1607-1609.

47 Ries S, Steinke W, Neff KW, et al. Echocontrast-enhanced transcranial color-coded sonography for the diagnosis of transverse sinus venous thrombosis. Stroke. 1997;28:696-700.

48 Knudson MM, Ikossi DG. Venous thromboembolism after trauma. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2004;10:539-548.

49 Canhao P, Batista P, Falcao F. Lumbar puncture and dural sinus thrombosis—a causal or casual association? Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;19:53-56.

50 Aidi S, Chaunu MP, Biousse V, et al. Changing pattern of headache pointing to cerebral venous thrombosis after lumbar puncture and intravenous high-dose corticosteroids. Headache. 1999;39:559-564.

51 de Bruijn SF, Stam J, Koopman MM, et al. Case-control study of risk of cerebral sinus thrombosis in oral contraceptive users and in (correction of who are) carriers of hereditary prothrombotic conditions. The Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis Study Group. BMJ. 1998;316:589-592.

52 Buccino G, Scoditti U, Pini M, et al. Low-oestrogen oral contraceptives as a major risk factor for cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis: evidence from a clinical series. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1999;20:231-235.

53 Vander T, Medvedovsky M, Shelef I, et al. Postmenopausal HRT is not independent risk factor for dural sinus thrombosis. Eur J Neurol. 2004;11:569-571.

54 Derex L, Philippeau F, Nighoghossian N, et al. Postpartum cerebral venous thrombosis, congenital protein C deficiency, and activated protein C resistance due to heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:801-802.

55 Cantu C, Barinagarrementeria F. Cerebral venous thrombosis associated with pregnancy and puerperium: review of 67 cases. Stroke. 1993;24:1880-1884.

56 Martinelli I, Battaglioli T, Pedotti P, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia in cerebral vein thrombosis. Blood. 2003;102:1363-1366.

57 Baumeister FA, Auberger K, Schneider K. Thrombosis of the deep cerebral veins with excessive bilateral infarction in a premature infant with the thrombogenic 4G/4G genotype of the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Eur J Pediatr. 2000;159:239-242.

58 Cattaneo M. Hyperhomocysteinemia, atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 1999;81:165-176.

59 Gupta M, Gupta S, Saxena R, et al. Familial hyperhomocysteinemia: multiple venous thrombosis in four generations of a family. Ann Hematol. 2003;82:178-180.

60 Harpel PC, Zhang X, Borth W. Homocysteine and hemostasis: pathogenic mechanisms predisposing to thrombosis. J Nutr. 1996;126(4, Suppl):S1285-S1289.

61 Ventura P, Cobelli M, Marietta M, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia and other newly recognized inherited coagulation disorders (factor V Leiden and prothrombin gene mutation) in patients with idiopathic cerebral vein thrombosis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;17:153-159.

62 Farstad H, Gaustad P, Kristiansen P, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis and Escherichia coli infection in neonates. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92:254-257.

63 Benedict SL, Bonkowsky JL, Thompson JA, et al. Cerebral sinovenous thrombosis in children: another reason to treat iron deficiency anemia. J Child Neurol. 2004;19:526-531.

64 Kakkar N, Banerjee AK, Vasishta RK, et al. Aseptic cerebral venous thrombosis associated with abdominal tuberculosis. Neurol India. 2003;51:128-129.

65 Brucker AB, Vollert-Rogenhofer H, Wagner M, et al. Heparin treatment in acute cerebral sinus venous thrombosis: a retrospective clinical and MR analysis of 42 cases. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1998;8:331-337.

66 Benamer HT, Bone I. Cerebral venous thrombosis: anticoagulants or thrombolytic therapy? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:427-430.

67 Einhaupl KM, Villringer A, Meister W, et al. Heparin treatment in sinus venous thrombosis. Lancet. 1991;338:597-600.

68 Stam J, de Bruijn S, deVeber G. Anticoagulation for cerebral sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 2003;34:1054-1055.

69 Stam J, de Bruijn SF, DeVeber G. Anticoagulation for cerebral sinus thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2002. CD002005

70 de Bruijn SF, Stam J. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of anticoagulant treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin for cerebral sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 1999;30:484-488.

71 Lewis MB, Bousser MG. Cerebral venous thrombosis: nothing, heparin, or local thrombolysis? Stroke. 1999;30:1729.

72 Bousser MG. Cerebral venous thrombosis: nothing, heparin, or local thrombolysis? Stroke. 1999;30:481-483.

73 Bates SM, Greer IA, Hirsh J, et al. Use of antithrombotic agents during pregnancy: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126(3, Suppl):627S-644S.

74 Aoki N, Uchinuno H, Tanikawa T, et al. Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis treated with combined local thrombolytic and systemic anticoagulation therapy. Acta Neurochir. 1997;139:332-335.

75 D’Alise MD, Fichtel F, Horowitz M. Sagittal sinus thrombosis following minor head injury treated with continuous urokinase infusion. Surg Neurol. 1998;49:430-435.

76 Ciccone A, Canhao P, Falcao F, et al. Thrombolysis for cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 2004;35:2428.

77 Di Rocco C, Iannelli A, Leone G, et al. Heparin-urokinase treatment in aseptic dural sinus thrombosis. Arch Neurol. 1981;38:431-435.

78 Eskridge JM, Wessbecher FW. Thrombolysis for superior sagittal sinus thrombosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1991;2:89-93.

79 Frey JL, Muro GJ, McDougall CG, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis: combined intrathrombus rtPA and intravenous heparin. Stroke. 1999;30:489-494.

80 Gebara BM, Goetting MG, Wang AM. Dural sinus thrombosis complicating subclavian vein catheterization: treatment with local thrombolysis. Pediatrics. 1995;95:138-140.

81 Horowitz M, Purdy P, Unwin H, et al. Treatment of dural sinus thrombosis using selective catheterization and urokinase. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:58-67.

82 Kim SY, Suh JH. Direct endovascular thrombolytic therapy for dural sinus thrombosis: infusion of alteplase. Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:639-645.

83 Canhao P, Falcao F, Ferro JM. Thrombolytics for cerebral sinus thrombosis: a systematic review. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;15:159-166.

84 Ciccone A, Canhao P, Falcao F, et al. Thrombolysis for cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2004. CD003693

85 Gerszten PC, Welch WC, Spearman MP, et al. Isolated deep cerebral venous thrombosis treated by direct endovascular thrombolysis. Surg Neurol. 1997;48:261-266.

86 Spearman MP, Jungreis CA, Wehner JJ, et al. Endovascular thrombolysis in deep cerebral venous thrombosis. Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:502-506.

87 Ferro JM, Lopes GC, Rosas MJ, et al. Do randomised clinical trials influence practice? The example of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis. J Neurol. 2002;249:1595-1596.

88 Wasay M, Bakshi R, Kojan S, et al. Nonrandomized comparison of local urokinase thrombolysis versus systemic heparin anticoagulation for superior sagittal sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 2001;32:2310-2317.

89 Barnwell SL, Nesbit GM, Clark WM. Local thrombolytic therapy for cerebrovascular disease: current Oregon Health Sciences University experience (July 1991 through April 1995). J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1995;6(6, Pt 2 Su):78S-82S.

90 Rottger C, Madlener K, Heil M, et al. Is heparin treatment the optimal management for cerebral venous thrombosis? Effect of abciximab, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator, and enoxaparin in experimentally induced superior sagittal sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 2005;36:841-846.

91 Curtin KR, Shaibani A, Resnick SA, et al. Rheolytic catheter thrombectomy, balloon angioplasty, and direct recombinant tissue plasminogen activator thrombolysis of dural sinus thrombosis with preexisting hemorrhagic infarctions. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:1807-1811.

92 Opatowsky MJ, Morris PP, Regan JD, et al. Rapid thrombectomy of superior sagittal sinus and transverse sinus thrombosis with a rheolytic catheter device. Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:414-417.

93 Dowd CF, Malek AM, Phatouros CC, et al. Application of a rheolytic thrombectomy device in the treatment of dural sinus thrombosis: a new technique. Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:568-570.

94 Baker MD, Opatowsky MJ, Wilson JA, et al. Rheolytic catheter and thrombolysis of dural venous sinus thrombosis: a case series. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:487-493.

95 Scarrow AM, Williams RL, Jungreis CA, et al. Removal of a thrombus from the sigmoid and transverse sinuses with a rheolytic thrombectomy catheter. Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:1467-1469.

96 Chaloupka JC, Mangla S, Huddle DC. Use of mechanical thrombolysis via microballoon percutaneous transluminal angioplasty for the treatment of acute dural sinus thrombosis: case presentation and technical report. Neurosurgery. 1999;45:650-656.

97 Chow K, Gobin YP, Saver J, et al. Endovascular treatment of dural sinus thrombosis with rheolytic thrombectomy and intraarterial thrombolysis. Stroke. 2000;31:1420-1425.

98 Gomez CR, Misra VK, Terry JB, et al. Emergency endovascular treatment of cerebral sinus thrombosis with a rheolytic catheter device. J Neuroimaging. 2000;10:177-180.

99 Baker MD, Opatowsky MJ, Wilson JA, et al. Rheolytic catheter and thrombolysis of dural venous sinus thrombosis: a case series. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:487-493. discussion, 493–494.

100 Ekseth K, Bostrom S, Vegfors M. Reversibility of severe sagittal sinus thrombosis with open surgical thrombectomy combined with local infusion of tissue plasminogen activator: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:960-965.

101 Chahlavi A, Steinmetz MP, Masaryk TJ, et al. A transcranial approach for direct mechanical thrombectomy of dural sinus thrombosis: report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:347-351.

102 Preter M, Tzourio C, Ameri A, et al. Longterm prognosis in cerebral venous thrombosis: follow-up of 77 patients. Stroke. 1996;27:243-246.

103 Ferro JM, Lopes MG, Rosas MJ, et al. Longterm prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: results of the VENOPORT study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;13:272-278.

104 Ferro JM, Lopes MG, Rosas MJ, et al. Delay in hospital admission of patients with cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;19:152-156.

105 Breteau G, Mounier-Vehier F, Godefroy O, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis 3-year clinical outcome in 55 consecutive patients. J Neurol. 2003;250:29-35.

106 Brill-Edwards P, Ginsberg JS, Gent M, et al. Safety of with-holding heparin in pregnant women with a history of venous thromboembolism. Recurrence of Clot in This Pregnancy Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1439-1444.

107 Stolz E, Trittmacher S, Rahimi A, et al. Influence of recanalization on outcome in dural sinus thrombosis: a prospective study. Stroke. 2004;35:544-547.