77 Cerebral Palsy

Clinical Presentation

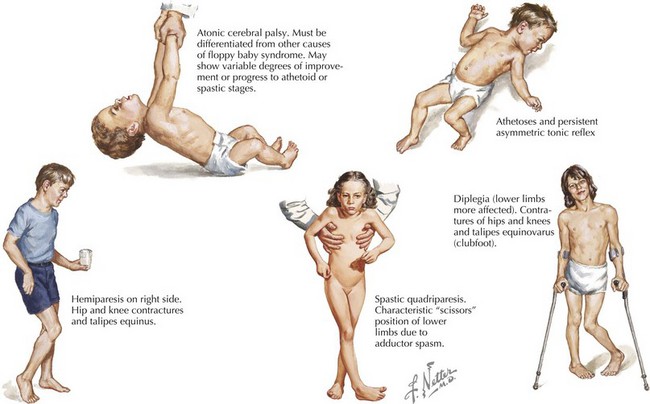

Some children with CP have recognized risk factors (e.g., prematurity and low birth weight) leading to early neurologic and developmental screening. In these children, follow-up visits or early intervention evaluations should include serial assessments of tone and motor development. In the first few months, early signs may include low tone or decreased movements in affected limbs (Figure 77-1). However, not all such clinical presentations progress to CP. Although severe CP may be evident in the first months of life, it is generally difficult to make a definitive diagnosis before 1 year of age. Some clinicians advise not giving the diagnosis to a child younger than 2 years of age. This is because many children identified as having tone or motor abnormalities before 12 months of age will be free of symptoms by school age. Caution is necessary to avoid overdiagnosis in infancy.

Spastic Cerebral Palsy

Spastic CP is the most common type, comprising about 70% of cases. It may be further subdivided according to the pattern of limb involvement. Spastic diplegia primarily involves the lower limbs and may be symmetric or asymmetric (see Figure 77-1). Parents often give a history of “tiptoeing” even when walking holding on to furniture. Spastic hemiparesis involves the upper and lower limb on one side, usually with the upper extremity more affected than the lower (see Figure 77-1). Parents may report early handedness (before 2 years) or that the child did not support his or her weight as well on the affected side when crawling. Spastic quadriparesis evenly involves all four limbs (see Figure 77-1).

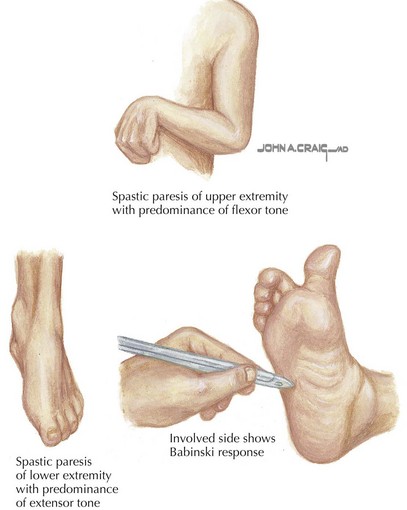

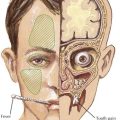

Spastic CP is characterized on physical examination by signs of an upper motor neuron syndrome, indicating a CNS process. On observation, the clinician may see a characteristic pattern in spastic limbs (Figure 77-2). Affected upper extremities have a tendency toward flexion at the elbow and wrist, with pronation of the forearm and fingers kept closed or fisted. Affected hips are adducted and are “scissored” in extreme cases. There is partial flexion at the knees and plantarflexion at the ankles. Torticollis and truncal hyperextension or twisting may also be present. After inspection, the clinician may perform passive range of motion, revealing increased tone in the affected limb. Typical of spasticity is “velocity dependence, meaning resistance increases with more rapid passive movement. In some cases, a spastic “catch” may be elicited in a limb with passive joint extension in which the increase in tone is momentarily reduced. Tone may also be increased in states of stress or excitement and decreased in sleep. In long-standing or severe cases, range of motion may be limited by secondary joint contractures, which typically evolve later in infancy or childhood. Strength may be intact, although this varies, and an element of weakness and motor fatigue is common. Reflex testing reveals hyperreflexia. This is the result of a hyperexcitable stretch reflex and in extreme forms presents as clonus. Extensor plantar responses (i.e., Babinski’s sign) may be present on the affected side. Children with spastic CP may experience difficulties with fine motor movements (e.g., sequential finger movements) or in isolated effortful movements. In mild cases, this may appear as “clumsiness” with easy fatigability. Observation of gait is helpful both in recognizing the pattern of involvement and in assessing functional impairment.

Dyskinetic Cerebral Palsy

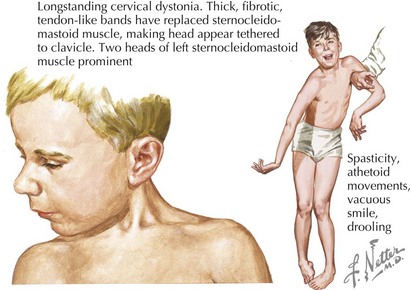

Dyskinetic CP comprises about 15% of CP. Involuntary movements interfering with voluntary motor function are characteristic. Dyskinetic CP may be further divided by primary movement type into choreoathetoid CP and dystonic CP (Figure 77-3). Choreoathetoid movements have a smooth, fluctuating dancelike quality (chorea) and a writhing or wriggling quality (athetosis) in the distal extremities. Dystonia is abnormal sustained movement or posturing in a repetitive, patterned fashion. Although dystonias are also quite common in spastic CP, dystonic CP refers to the case in which dystonia is the primary feature. Even in retrospect, dyskinetic CP may not be noticed until after age 2 or 3 years because infants without CP have some degree of choreoathetoid movement. The movement disorder in dyskinetic CP reflects injury to the basal ganglia. Clinical history should explore risk factors for such injury, including hyperbilirubinemia or hypoxic ischemic injury at term or postnatally. Children with dyskinetic CP are often described as having “fluctuating tone.” This reflects involuntary, often sustained muscle contraction that may be mistaken for intermittent spasticity. The physical examination should include observation of involuntary movements, recognizing that multiple movement types may be present. Sustained posture (e.g., extension of the arms) or distraction may elicit involuntary movements. Serial assessments of tone may be necessary to characterize whether spasticity is also present.

Evaluation and Management

Initial and follow-up visits should include screens for other conditions commonly associated with CP (Table 77-1). The pediatrician should identify these conditions and refer the patient for further evaluation and management when appropriate. Although CP itself is not curable, many commonly associated conditions are highly amenable to treatment and may impact quality of life even more than the motor impairment itself. Furthermore, mortality in CP is almost always caused by secondary difficulties, such as aspiration.

Table 77-1 Conditions Commonly Associated with Cerebral Palsy

| System | Condition (Prevalence Among Children with Cerebral Palsy) |

|---|---|

| Neurodevelopmental | Speech or language disorder (38%-59%) |

| Seizures (25-45%) | |

| Cognitive impairment (25%-75%) | |

| Sensory | Strabismus or refractive error (50%) |

| Vision impairment (10%-39%) | |

| Hearing impairment (4%-15%) | |

| Nutrition | Malnutrition |

| Excess adipose tissue | |

| Gastrointestinal | Constipation (74%) |

| Swallowing dysfunction (60%) | |

| Reflux (32%) | |

| Respiratory | Aspiration (41%) |

| Orthopedic | Osteopenia |

| Hip subluxation | |

| Scoliosis | |

| Genitourinary | Voiding dysfunction (30%) |

Ashwal S, Russman BS, Blasco PA, et al. Practice parameter: diagnostic assessment of the child with cerebral palsy: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2004;62(6):851-863.

Cooley WC. Providing a primary care medical home for children and youth with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):1106-1113.

Tilton A. Management of spasticity in children with cerebral palsy. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2009;16(2):82-89.

Wood E. The child with cerebral palsy: diagnosis and beyond. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2006;13(4):286-296.