CHAPTER 43 Cerebellar Convexity Meningiomas

HISTORY

In 1938, Cushing reported his own experience with 313 cases of meningioma operated in the early 20th century. Fifteen of these cases were cerebellar convexity meningiomas.1 He classified these meningiomas as cerebellar chamber, subtentorial and recess tumors. He operated all those meningiomas during the 29 years from 1903 to 1932 and described the clinical and surgical record of each case precisely. Among his cases was a 27-year-old woman with a cerebellar convexity meningioma. She had complained of right facial numbness and tinnitus for 1 year, had stiffness of her neck for 3 months, and showed ataxic unsteady gait. She also had disturbance of vision, and on funduscopy choked discs were observed. Cushing operated this patient with a diagnosis of cerebellar tumor in two stages. The first operation was performed on February 11, 1913 and he made bilateral cerebellar explorations an atlas laminectomy to prevent tonsilar herniation. The second operation was performed 11 days later, on February 22, 1913 and the tumor was completely removed. The weight of the tumor was 56 grams. Cushing diagnosed this tumor as a fibroblastic meningioma with no psammomatous depositions and only slight tendency to the formation of whorls. The patient was in excellent condition with no neurological deficits in 1937, 24 years after the tumor removal. Cushing stated that generally speaking, these cases have proved to be surgically favorable, even those operated upon at a time when there had been little experience with what were still called “dural endotheliomas,” all of which supposedly had a good ultimate prognosis if the bulk of the lesion was removed. Among 15 cases of cerebellar convexity meningiomas operated by Cushing, 11 cases demonstrated long survival time after the surgical removal of the tumor and were in good clinical condition.

In the later literature, Castellano and Ruggiero2 classified posterior fossa meningiomas into five subgroups: cerebellar convexity, tentorium, posterior petrous, clivus, and foramen magnum meningiomas. In 1953, Russel and Bucy3 mentioned the difficulties on diagnosis of posterior fossa meningiomas. Huang and Wolf 4 published their detailed description of the venous phase of the vertebral arteriography for diagnosis of posterior fossa tumors. It is obvious that the invention of CT and MRI ameliorated the diagnosis for cerebellar convexity meningiomas.5 In their detailed description of basal posterior fossa meningiomas, Yasargil and colleagues6 classified cerebellar meningiomas as the fourth group of dorsal meningiomas and divided them into median, paramedian, and lateral lesions. Since the 1970s, with the introduction of the CT scan and the development of microsurgical techniques and cranial base approaches, the surgical management of cerebellar convexity meningiomas have been evolving, leading to better outcome and a marked fall in surgical morbidity and mortality. The operative mortality rate was 22% in 1938 that published by Cushing.1 In 1979 it was improved to 4% with the series of Yasargil.6 Two recent reports indicated no operational mortality.7,8 Gross total resection must be the treatment of choice in all types of cerebellar convexity meningiomas. Roberti and colleagues8 reported 77% gross total resection with no mortality and morbidity. The most common cause for an incomplete resection was adherence of the tumor to cranial nerves or vascular structures, particularly venous sinuses that could not be sacrificed. If a complete resection presents an unacceptable risk of neurologic deficit, then a subtotal removal should be considered, and adjuvant treatment contemplated.

INCIDENCE

The location of meningiomas reported in the Japan Brain Tumor Registry9 is shown in Table 43-1. In total 13,838 meningiomas registered, 324 cases (2.3% of all meningiomas) were cerebellar convexity meningiomas. The ratio of supra- to infratentorial convexity meningiomas was 11:1. In the literature, cerebellar convexity meningiomas account for 8% to 18% of all posterior fossa meningiomas and 1% to 2% of all meningiomas.2,10–12 According to the Japan Brain Tumor Registry, they account 12.3% (324/2,629 all posterior fossa meningiomas). The number of meningiomas in posterior fossa other than cerebellar convexity were 877 cases (6.3%) in the cerebellopontine angle (CPA), 1041 (7.5%) in the tentorium, 226 (1.6%) in the clivus, 12 (0.1%) in fourth ventricle, and 149 (1.1%) in the foramen magnum. Some of the cerebellar convexity meningiomas were closely located or attached to the tentorium, CPA, or foramen magnum.

| Location | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Parasagittal | 1591 | 11.5 |

| Falx | 1608 | 11.6 |

| Supratentorial convexity | 3556 | 25.8 |

| Sphenoid ridge | 1422 | 10.3 |

| Olfactory groove | 499 | 3.6 |

| Parasellar | 1015 | 7.3 |

| Middle fossa | 344 | 2.5 |

| Ventricle | ||

| Lateral | 191 | 1.4 |

| Third | 13 | 0.1 |

| Fourth | 12 | 0.1 |

| Not specified | 1 | 0.0 |

| Cerebellopontine angle | 877 | 6.3 |

| Tentorium | 1041 | 7.5 |

| Clivus | 226 | 1.6 |

| Cerebellar convexity | 324 | 2.3 |

| Foramen magnum | 149 | 1.1 |

| Others or not specified | 969 | 7.0 |

| Total | 13,838 | 100.0 |

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Patients with cerebellar convexity meningiomas generally present with a long history of heaviness in the head, headache, neck stiffness, dizziness, and tinnitus and sometimes show ataxic gait. Cerebellar signs are often demonstrated via neurologic examinations. Unlike in the other types of posterior fossa meningiomas, cranial nerve deficits are not commonly encountered in cerebellar convexity meningiomas, due to the presence of cerebellar parenchymal tissue between the tumor and the cranial nerves. However; Grand and Bakay13 reported a 50% of papilledema in patients with cerebellar meningiomas. Roberti8 commented that the head pain was the most common symptom in cerebellar convexity meningiomas and other symptoms were gait ataxia and dysmetria. The site of origin of the tumor is reported to have an effect on the nature of the presentation. Patients with cerebellar convexity meningioma may present with progressive cerebellar signs, signs of increased intracranial pressure and symptoms of hydrocephalus. These meningiomas are often found incidentally on CT when the patient presents with head trauma, cerebrovascular disease, or other brain tumors. According to the literature, the duration of symptoms before diagnosis varies widely. According to Cudlip and colleagues,14 mean time to presentation was 24 months (range 0 ± 240 months). Acute presentations have also been reported, such as loss of consciousness due to hydrocephalus and raised intracranial pressure.

The differential diagnosis from tentorial, CPA, clivus or foramen magnum is important. Patients with tentorial meningioma show symptoms of cerebellar and brain stem compression and also occipital or temporal lobe compression such as visual hallucination or homonymous visual field deficits. Patients with CPA meningioma show symptoms of headache, hearing loss, vertigo, tinnitus, facial numbness, and signs of nystagmus, ataxia, facial hypesthesia and weakness.15 In cases of clival meningioma, common symptoms are headache, gait disturbance, vertigo, and visual and hearing disturbances. The common signs are trigeminal sensory deficit, ataxic gait, facial palsy, pharyngeal weakness, and hemi- or monoparesis.6,16 Patients with foramen magnum meningioma show cervical and suboccipital pain in the early stage. Hand and arm paresthesias, gait disturbance, and weakness of arms and legs are common symptoms. It was reported that 25% of patients with foramen magnum meningioma have spinal accessory nerve involvement and horizontal nystagmus.17

RADIOLOGIC IMAGING

Cerebellar convexity meningiomas can be reliably diagnosed via MRI or CT. Differential diagnosis from tentorial, CPA, clivus, or foramen magnum meningiomas is also definitive via MRI. MRI usually reveals a tumor that is isointense (60% of cases) or mildly hypointense (30%) on T1-weighted images, and isointense (50%) or moderately hyperintense (40%) on T2-weighted images.5 MRI is especially useful because the location of the tumor, attachment to the tentorium, and involvement of cerebellar hemispheric vessels and venous sinuses can be demonstrated easily. Digital subtraction angiography is not essential for diagnosis of cerebellar convexity meningiomas. However, angiography can aid in the diagnosis of tumor invasion to the transverse sinus or tentorial venous sinuses.

SURGICAL TREATMENT

As in all benign tumors, a radical surgical excision remains the ideal treatment and is best accomplished in a single operation, preferably as the patient’s first. As mentioned earlier, cerebellar convexity meningiomas are classified into three groups: medial, lateral, and superior.6,18 Surgical treatment differs for these three subtypes.

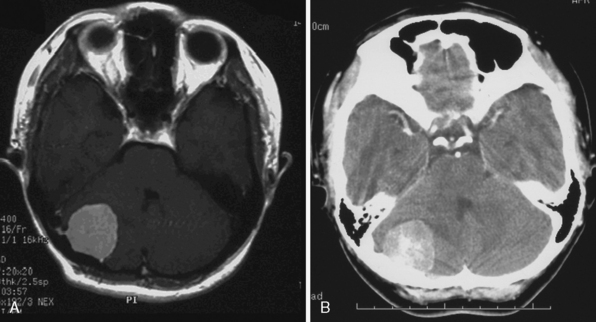

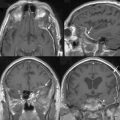

In the medial type, the dural attachment does not extend more than 3 cm lateral to the midline.6,18 Surgical exposure of medial cerebellar convexity meningiomas is simple and straightforward and performed in the prone position without head rotation. We prefer a prone position with 15- to 30-degree elevation of the patient’s upper body. Others have reported operation in the sitting position; however, the sitting position is not preferred because of widely known risks.6 A linear skin incision and bilateral suboccipital craniectomy are performed. The head rotation about 30 degrees and J-shaped skin incision is used occasionally. Posterior fossa craniectomy or craniotomy is performed after the skin incision in the midline or on the side of the tumor, depending on the size and location of the tumor. Posterior fossa craniectomy should be extended to the foramen magnum. When the tumor extends to or over the tentorium, the hockey-stick skin incision and craniotomy is generally performed in the upper region of the posterior fossa. If the tumor invades to dura mater and occipital bone, that part of dura or bone is coagulated well and removed. The tumor is lifted and dissected from the cerebellar tissue as similar fashion to the supratentorial convexity meningioma. If the falx cerebelli or the occipital sinus is involved by the tumor, they can be resected. Depending on its size, the tumor may be removed en block or after intratumoral decompression. Intratumoral decompression and dissection from the surrounding anatomical structures is safer, as vascular structures can be protected. When removing the tumor, care should be taken to preserve the vermian branch of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery. A demonstrative case of the medial type cerebellar convexity meningioma is presented in Figure 43-1.

FIGURE 43-1 MRI of left cerebellar convexity meningioma. A, T1-weighted image. B, T2-weighted image.

Lateral cerebellar convexity meningiomas frequently involve the sigmoid sinus. The patient may be operated in the prone position with head rotation or in the lateral position. A paramedian linear or a J-shaped skin flap is used. The craniectomy extends laterally to the sigmoid sinus and superiorly to the transverse sinus far enough to allow adequate tumor exposure.19 Excessive exposure of the sinuses is, however, avoided.

The superior type is attached to the tentorium cerebelli. The concord or the sitting positions provide a better view to the tentorial attachment than the simple prone position. A linear or reverse U incision is used. If the transverse sinus is to be included in the surgical procedure, a supratentorial craniotomy may be added. The sinus can be resected safely if its lumen is completely occluded by tumor.20 If the sinus is only partially involved, the decision of whether to attempt complete resection rests on several factors related to the dural sinuses and venous anatomy: whether the involved sinus is dominant and whether both transverse sinuses communicate at the torcular. If the transverse sinus is to be resected, careful attention must be paid to preserving the cortical venous drainage, particularly of the ipsilateral vein of Labbé.21,22 Reconstruction of the sinus with a pericranial or venous graft has been reported in the literature; however, reconstruction of venous sinuses has a low success rate and carries a significant risk of morbidity and mortality.

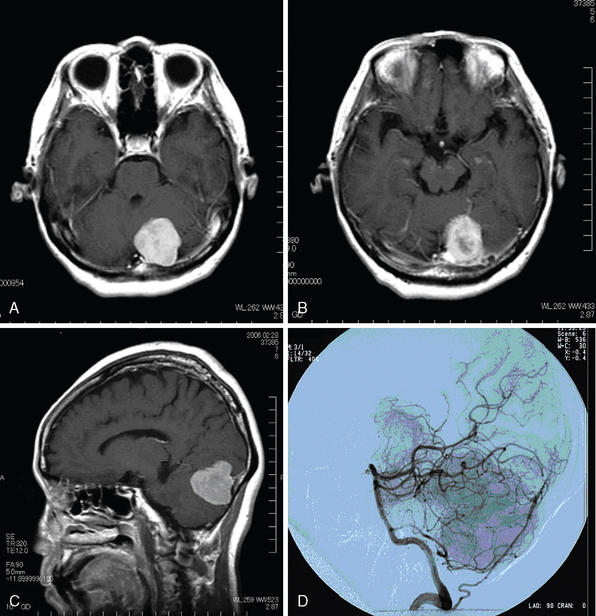

A 58-year-old woman presented with a history of headaches of several months duration. On examination the patient had slight left cerebellar signs. MRI demonstrated a tumor in her left cerebellar hemisphere (Fig. 43-2). Angiography revealed that the feeding artery was not the tentorial artery but the left occipital artery. The tumor was embolized before surgical resection. The operation was performed in the prone position with a 30-degree elevation of her upper body. A hockey-stick incision was made from the left temporoparietal region to the midline and down to the C2 level. Craniotomy was made with five burr holes drilled above and under the transverse sinus. After a suboccipital craniectomy, the foramen magnum was opened, and C1 laminecotmy was added. The tumor invaded to the dura mater and the occipital bone. The tumor was whitish yellow and not very hemorrhagic. Intratumoral decompression and piecemeal removal of the tumor was performed. After decompression, the residual tumor was removed. The left side of the transverse sinus was filled with the tumor and completely occluded. Therefore, that part of the transverse sinus was coagulated and removed. The tentorium invaded by the tumor was also removed. Pathologic diagnosis of the tumor was meningothelial meningioma, and the postsurgical course was uneventful.

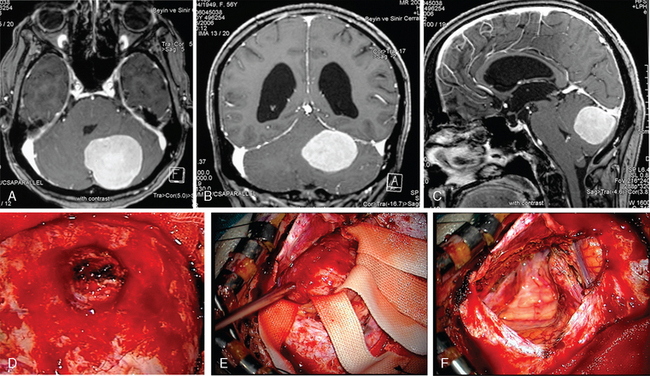

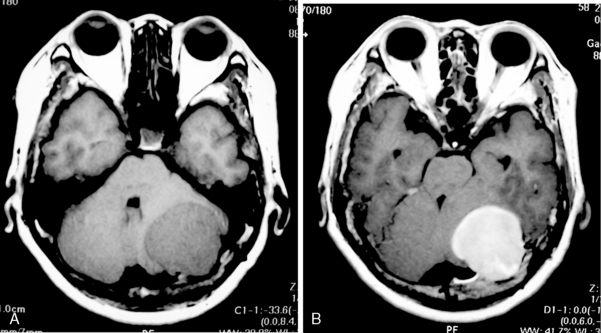

A 45-year-old woman complained of headache, dizziness, and ataxic gait. MRI (Fig. 43-3A) revealed a right cerebellar convexity meningioma. CT scan (Fig. 43-3B) demonstrated calcification inside the tumor. The tumor invaded the dura mater and occipital bone. The tumor was completely removed with attached dura mater and the part of the bone. The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient is in excellent condition without any neurologic signs and symptoms at 10 years after the surgical removal of the tumor.

A 60-year-old woman complained of headache and the left cerebellar tumor (Fig. 43-4A) was demonstrated. The tumor invaded the dura mater and occipital bone (Fig. 43-4B) and extended to the supratentorial region (Fig. 43-4C). Angiography revealed that the tumor was fed by the occipital artery and the transverse sinus was partially occluded by the tumor. The operation was performed in the prone position. The thorax was elevated 15 degrees. A hockey-stick incision was made and the suboccipital muscle was incised at midline. Craniotomy was performed in the left supra- and infratentorial area. The tumor was whitish and hard and the transverse sinus was almost occluded by the tumor. The sinus was ligated and incised at both sides of the tumor. After devascularization and detachment from the tentorium, the tumor was removed en block. The remained tentorium was coagulated well. The pathological diagnosis was meningothelial meningioma. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient is well at 2 years after the surgery. This tumor was considered as tentorial meningioma initially, but the tumor invaded the dura and occipital bone, and it was fed by the occipital artery and thus a diagnosis of cerebellar convexity meningioma may be more accurate.

[1] Cushing H., Eisenhardt L. Meningiomas, Their Classification, Regional Behavior, Life History and Surgical Results. New York: Hafner, 1938.

[2] Castellano F., Ruggiero G. Meningiomas of the posterior fossa. Acta Radiol. 1953;104(Suppl.):1-177.

[3] Russel J.R., Bucy P.C. Meningiomas of the posterior fossa. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1953;96:183-192.

[4] Huang Y.P., Wolf B.S. Precentral cerebellar vein in angiography. Acta Radiol Diagn. 1966;5:595-598.

[5] Nagele T., Petersen D., Klose U., et al. The “dural tail” adjacent to meningiomas studied by dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI: a comparison with histopathology. Neuroradiology. 1994;36:303-307.

[6] Yasargil M.G., Mortara R.W., Carcic M. Meningiomas of basal posterior cranial fossa. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg. 1980;7:3-115.

[7] Martínez R., Vaquero J., Areitio E., Bravo G. Meningiomas of the posterior fossa. Surg Neurol. 1983;19(3):237-243.

[8] Roberti F., Sekhar L.N., Kalavakonda C., Wright D.C. Posterior fossa meningiomas: surgical experience in 161 cases. Surg Neurol. 2001;56(1):8-20. discussion 20–1

[9] Committee of Brain Tumor Registry of Japan. Report of Brain Tumor Registry of Japan. Neurol Med Chir. 2003;43(Suppl.):5-18.

[10] Martinez R., Vaquero J., Areitio E., Bravo G. Meningiomas of the posterior fossa. Surg Neurol. 1983;19:237-243.

[11] Markham J.W., Fager C.A., Horrax G. Meningiomas of the posterior fossa. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1955;74:163-170.

[12] Russel J.B., Bucy P.C. Meningiomas of the posterior fossa. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1953;96:183-192.

[13] Grand W., Bakay L. Posterior fossa meningiomas. A report of 30 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1975;32(3–4):219-233.

[14] Cudlip S.A., Wilkins P.R., Johnston F.G., Moore A.J., Marsh H.T., Bell B.A. Posterior fossa meningiomas: surgical experience in 52 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1998;140:1007-1012.

[15] Granich M.S., Maturza R.L., Ojeman R.G., Parker S.W., Montgomery W.W. Cerebello-pontine angle meningiomas. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. Ann Otol Laryngol. 1985;94:34-38.

[16] Cherington M., Schneck S.A. Clivus meningiomas. Neurology. 1966;16:86-92.

[17] Meyer F.B., Ebersold M.J., Reese D.F. Benign tumors of the foramen magnum. J Neurosurg. 1984;61:136-142.

[18] Kobayashi S., Nakamura Y. Cerebellar convexity meningiomas. In: Al-Mefty O., Smith R.R., editors. Clival and Petroclival Meningiomas. New York: Raven Press; 1991:517-537.

[19] Symon L., Pell M., Singh L. Surgical management of posterior cranial fossa meningiomas. Br J Neurosurg. 1993;7:599-609.

[20] Mattle H.P., Wentz K.U., Edelman R.R. Cerebral venography with MR. Radiology. 1991;178:453-458.

[21] Koperna T., Tschabitscher M., Knosp E. The termination of the vein of “Labbe” and its microsurgical significance. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1992;118:172-175.

[22] Heros R.C. Lateral suboccipital approach for vertebral and vertebrobasilar artery lesions. J Neurosurg. 1986;64:559-562.