16 Central nervous system tumours

Introduction

Primary central nervous system (CNS) tumours can arise from any structures in the cranial vault. Around 4000 new patients with malignant brain tumours are diagnosed per year in the UK and 22,000 new patients in USA. There is a bimodal distribution with small peak in children (p. 323) and a steady increase starting at the age of 20 years. Males are more commonly affected, particularly with malignant tumours, whereas women have a higher rate of non-malignant tumours, particularly meningiomas.

Aetiology

Pathology

Box 16.1 shows WHO classification of brain tumours. WHO grading system (Box 16.2) is important in deciding management and prognosis. Molecular features can be incorporated in this grading system to yield important prognostic information. Clinico-pathological features of individual tumours are discussed later.

Box 16.1

WHO classification of brain tumours

Box 16.2

WHO grading of primary CNS tumours

Investigations

Imaging

CT scan

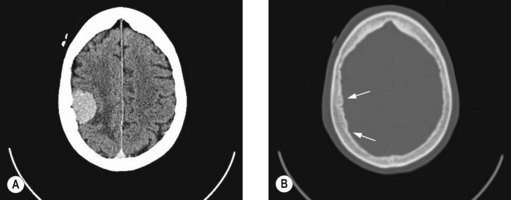

Contrast enhanced CT scan is usually the initial investigation in patients suspected to have a brain lesion. CT scan is not an ideal investigation for low-grade tumours or tumours in the posterior fossa. CT scan may also show features of oedema, hydrocephalus, haemorrhage and calcification depending on the histological variant of brain tumour. Table 16.1 shows radiological appearance of common tumours.

| Type of tumour | Imaging characteristic |

|---|---|

| Pilocystic astrocytoma | Well-circumscribed, contrast enhancing tumour with a cystic or enhancing mural nodule. |

| Grade II astrocytoma | Isodense or hypodense on CT. Hypointense on T1W image and hyperintense on T2W and FLAIR images. No contrast enhancement and if present suggest malignant transformation. No associated cerebral oedema. |

| Oligodendroglioma | Same CT/MRI as grade II astrocytoma; but can be associated with areas of contrast enhancement, calcification and haemorrhage. |

| Anaplastic astrocytoma and GBM |

MRI scan

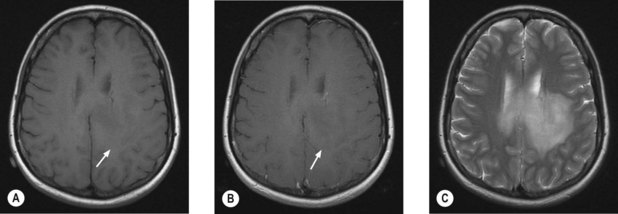

MRI scan with gadolinium and FLAIR (fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) sequence is the standard investigation for brain tumours. T1W imaging demonstrates anatomy and areas of contrast enhancement and T2W and FLAIR images are useful in demonstrating oedema. Appearance of tumour on T1W image is similar to that on CT, but better delineated on MRI. Tumour and oedema demonstrate increased signal on T2 and the area of increased T2 signal on MRI usually includes the hypodense area on CT (Figure 16.1).

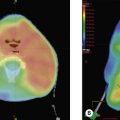

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)

In radiotherapy planning for high-grade gliomas, conventional methods of imaging cannot distinguish oedema from peritumoural white matter infiltration, resulting in large target volumes. DTI shows white matter abnormalities resulting from tumour infiltrating, and thereby reducing the target volume, which would allow significant dose escalation to the tumour with acceptable damage to the normal tissue.

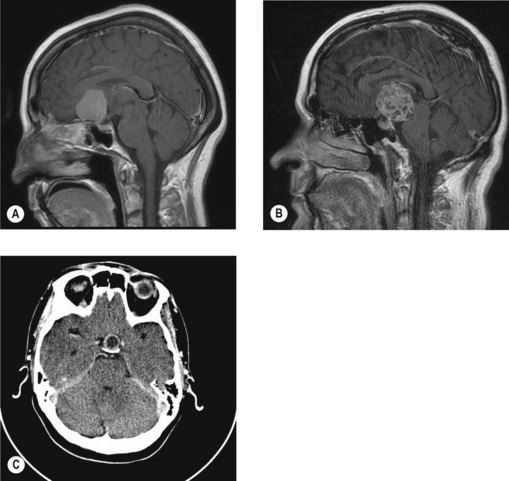

Evaluation of the craniospinal axis

MRI of the craniospinal axis and CSF evaluation is needed for tumours with a high risk of CSF dissemination such as medulloblastoma, germ cell tumours, CNS lymphoma, PNET and ependymoma (Figure 16.2). CSF evaluation includes CSF biochemistry (typically elevated protein >40 mg/dL and reduced glucose <50 mg/mL), cytology and in cases of suspected germ cell tumours, the estimation of tumour markers (AFP and beta hCG) in CSF and serum. Evaluation of the craniospinal axis is best done prior to surgery or >3 weeks after surgery to avoid false positive results.

Prognostic factors

The outcome of brain tumours depends on the following factors:

Principles of management

General medical management

Steroids

Steroids may improve symptoms by reducing intracranial pressure. The most commonly used agent is dexamethasone which is started at a dose of 2–16 mg daily (low doses given once daily and higher doses as 2–4 equally divided doses) and titrated against the patient’s symptoms. The optimal dose is just above that at which symptomatic deterioration occurs. If there is no symptomatic improvement, steroids should be stopped.

Surgical management

Surgery in brain tumours helps in pathological diagnosis, symptom control and definite treatment.

Radiotherapy in brain tumours

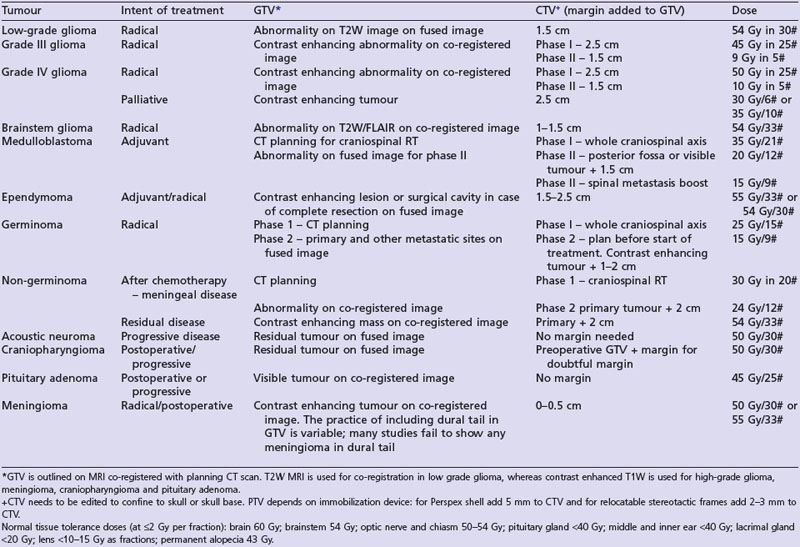

A summary of radiotherapy details for common tumours are given in Table 16.2.

Radiation tolerance and reactions

Acute radiation reactions may manifest up to 6 weeks following completion of irradiation. These reactions are generally those of raised intracranial pressure, fatigue and worsening of neurology. Vomiting is particularly common in patients receiving radiotherapy to the brainstem region.

Delayed radiation reaction develops 6 months after radiotherapy. This is thought to be due to white matter injury secondary to vascular injury, demyelination and necrosis. The most serious form of this is radiation necrosis which peaks at 3 years. Conventional imaging fails to distinguish this from recurrent tumour and special imaging is therefore needed (p. 265). Treatment is with steroids and debulking. Other late effects include, depending on the area irradiated, memory problems, pituitary failure, hearing loss, visual changes and second malignancies.

Chemotherapy in brain tumours

Chemotherapy has an established role in paediatric brain tumours mainly as a substitute for radiotherapy. The role of chemotherapy in adult brain tumours is increasing. The active agents are nitrosoureas (carmustine and lomustine), procarbazine, temozolomide, platinum and vincristine. The role of chemotherapy in specific brain tumours is discussed later in this chapter and the commonly used chemotherapy regimens are given in Box 16.3.

Clinico-pathological features and management of specific tumours

Glioma

Astrocytomas diffusely infiltrate surrounding brain. Pilocytic astrocytoma (grade 1) occurs in children and young adults and are located in the optic tract, hypothalamus, basal ganglia and posterior fossa. These tumours grow slowly and stabilize spontaneously. Diffuse astrocytoma (grade 2) is a low-grade tumour. Anaplastic astrocytoma (grade 3) and glioblastoma multiforme (grade 4-GBM) are high grade tumours. Anaplastic astrocytoma is distinguished from low-grade tumours by greater cellular differentiation and hyperchromasia, more frequent mitoses and prominent small vessels lined by epithelioid endothelial cells. Glioblastoma is distinguished by increased cellularity, pleomorphism, giant cells, abnormal mitotic figures and endothelial cell proliferation. Necrosis surrounded by nuclei aligned in pseudopalisading pattern is characteristic. Astrocytomas stain for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GAFP).

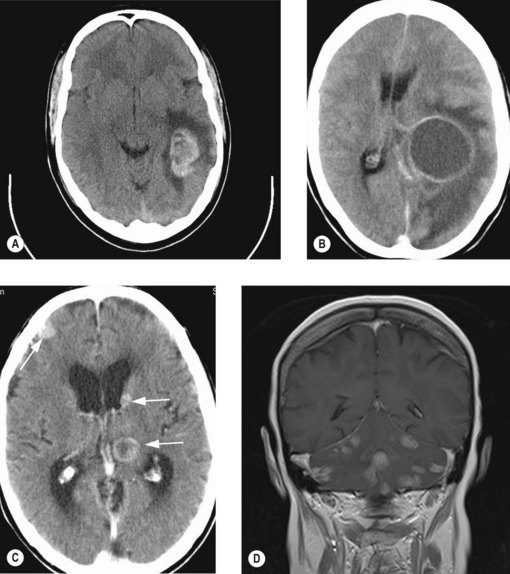

Treatment of low grade glioma (WHO grade 2)

Diffuse astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma (Figure 16.3) and mixed oligoastrocytoma are grouped together as low-grade glioma. These tumours mainly affect the young adults (mean age of 35 years for astrocytoma and 45 years for oligodendroglioma). Patients generally present with seizures and in the majority adequate seizure control with serial MRI monitoring will be sufficient. Many of these patients have slow growing tumours. There are two main patterns of progression – secondary gliomatosis cerebri and malignant transformation. Secondary gliomatosis cerebri is characterized by diffuse extension of the tumour sometimes to the opposite hemisphere and it often remains low-grade. Malignant transformation involves progression to a high-grade tumour with characteristics of anaplastic astrocytoma, anaplastic oligodendroglioma or glioblastoma. Imaging shows new areas of irregular contrast enhancement in a previously non-contrast enhancing tumour.

Surgery

The role of surgery in grade 2 tumours is unclear. When safe complete or near complete resection is feasible, it may be attempted. A recent retrospective study showed that gross total resection (complete resection of preoperative FLAIR abnormality) improved survival (10-year OS 76%) compared with near total resection (<3 mm thin residual FLAIR abnormality around resection cavity) (10-year OS 57%) and subtotal resection (residual nodular FLAIR abnormality) (10-year OS 49%; p = 0.017). Incomplete resection is only indicated to control specific symptoms such as seizures or intracranial pressure which may be relieved with removal of the appropriate region of tumour. The majority of patients are followed up or treated with non-surgical treatment after biopsy.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy can improve symptoms and lead to a radiologic response. The role of chemotherapy in newly diagnosed disease is however undefined. Chemotherapy is used in malignant transformation. Oligodendroglioma with allelic loss of chromosome 1p/19q usually responds to chemotherapy with alkylating agents (Box 16.3).

Treatment of high-grade (malignant) glioma (WHO grade 3 and 4)

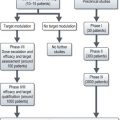

GBM

Adjuvant radiotherapy improves median survival of GBM from 14 weeks to 40 weeks and is given as a dose of 58–60 Gy in 1.8 to 2 Gy per fraction. Hence patients aged <70 years with good performance status (0–1) are considered for radical radiotherapy, whereas patients aged >70 years and performance status of 0–2 may be considered for short course radiotherapy. Patients with poor PS and significant neurological deficit are treated with supportive measures (Box 16.4).

Box 16.4

Treatment of glioma

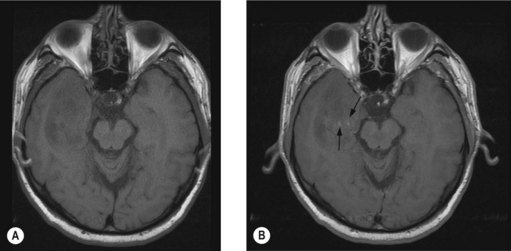

Management of recurrence and progression

In the majority of patients (>80%) with high-grade glioma, tumours recur within a 2–3 margin of the original tumour (Figure 16.4). Repeat surgery is an option for those with favourable prognostic features such as age <50 years, good performance status, progression free survival of >6 months and well circumscribed tumour, which offers a median survival of 6–8 months with 20% 1-year survival. In this group of patients polymer-based carmustine chemotherapy in a wafer (Gliadel) is proven to be useful. A randomized study showed an increased 6-month survival from 44% to 64% (p = 0.02) and median survival from 23 to 31 weeks with Gliadel wafers.

Brainstem glioma

Brainstem gliomas are rare in adults. Diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas are generally high grade whereas exophytic tumours are low grade. These tumours usually present as multiple cranial nerve paralysis, ataxia and hemiparesis. MRI shows diffuse enlargement of the pons on T1W images and enhancement is seen in high-grade glioma. Surgery is an appropriate treatment for exophytic low-grade lesions whereas inoperable low-grade lesions and intrinsic lesions are treated with involved field radiotherapy. The median survival of non-enhancing lesions is in the region of 7 years and of enhancing lesions is approximately 11 months.

Ependymoma

Ependymomas (grade 2) are slow growing tumours arising from the ependymal or subependymal cells surrounding the ventricles, spinal canal or filum terminale. These are typically low-grade but exhibit a high risk of recurrence and can spread through the CSF. They are rarely infiltrative and seldom metastasize outside CNS. Subependymoma, which occur in the cerebral ventricles and myxopapillary ependymoma, which occurs in the filum terminale are grade 1 variants of ependymoma. Histologically these tumours consist of uniform round cells with widespread pseudorosette formation. Maximal surgical resection followed by postoperative radiotherapy is the treatment of choice in adults (Table 16.2). Local radiotherapy is recommended if spinal MRI and CSF cytology are clear. Craniospinal RT is recommended only in cases of neuraxis spread. There is no recommended role for chemotherapy, except in recurrence after radiotherapy. Postoperative radiotherapy increases 5-year survival from 18% to 68%.

Medulloblastoma and PNET

Treatment of medulloblastoma and PNET

In medulloblastoma, the extent of surgical resection correlates with survival and hence, maximal surgical resection is attempted in localized disease. All patients are treated with postoperative craniospinal radiotherapy followed by additional radiotherapy to the posterior cranial fossa. Radiotherapy with concurrent vincristine followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin, CCNU and vincristine (Packer regime) is an effective regime (Box 16.3); but it is very toxic in adults (especially neurotoxicity) and hence sometimes radiotherapy alone may be used.

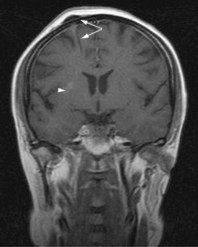

Meningeal tumours

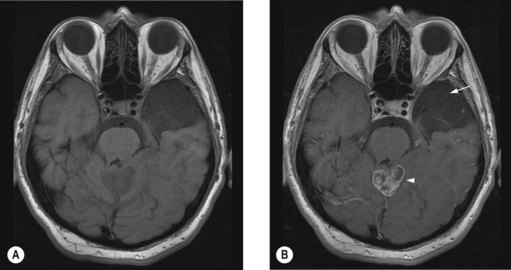

Meningiomas (Figure 16.5) account for 30% of primary intracranial neoplasms and occur predominantly in women. Grade 1 meningiomas (90% of meningiomas) are benign with a low risk of recurrence, atypical (grade 2) meningiomas (5–7%) have a high risk of local recurrence after complete excision and grade 3 meningiomas (3–5%) are aggressive. Papillary meningioma (grade 3) is seen in young patients, shows aggressive behaviour with frequent recurrences, brain invasion and metastasis. Anaplastic (malignant) meningioma is also aggressive.

Treatment of meningioma

Meningiomas can be observed if they are small and asymptomatic. Treatments of choice for progressive or symptomatic meningioma are either complete surgical resection if in an operable location or radical radiotherapy or radiosurgery, if in an inoperable site. Complete resection is usually difficult for skull base (Figure 16.6A), cavernous sinus and cerebellopontine angle meningiomas. After incomplete resection, either a policy of imaging surveillance with delayed radiotherapy on progression or immediate postoperative radiotherapy is adopted. The policy of image surveillance with delayed radiotherapy depends on:

Primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL)

PCNSL has a higher incidence in immunocompromised individuals than in the normal population. It commonly presents in the third and fourth decades in immunocompromised individuals whereas it occurs three decades later in those who have a competent immune system. The usual presentations include focal symptoms, raised intracranial pressure, behaviour and personality changes and confusion. Biopsy shows diffuse large cell B cell lymphoma in 80–90%. Up to 20–40% patients have CSF involvement. Less than 5% people have systemic involvement. Tissue diagnosis is made from an open or stereotactic biopsy. Staging investigations include HIV testing, chest X-ray, CSF examination and slit lamp examination (10–20% have uveitis). Systemic staging is only indicated if B symptoms are present (see p. 306).

The role of surgery is limited to biopsy. Steroids may cause complete disappearance of tumour (ghost tumours) and hence should be avoided until tissue diagnosis. Current standard treatment is high-dose intravenous methotrexate with whole brain radiotherapy (40–50 Gy) which results in a 2-year survival of 43–73%. However this treatment is extremely toxic particularly in the elderly when 60–80% patients older than 60 years develop progressive leucoencephalopathy and cognitive dysfunction. Hence in the elderly chemotherapy alone with delayed radiotherapy is an alternative. In immunocompromised patients reduction of radiotherapy dose may be necessary to reduce toxicity.

Craniopharyngioma

Craniopharyngioma (Figure 16.6B) arises from the epithelial remnants of Rathke’s pouch. These are slow growing tumours often with a solid and cystic component, the latter filled with a fluid having a ‘motor oil’ appearance.

Pituitary adenoma and carcinoma

Pituitary adenoma

Pituitary adenoma (Figure 16.6C) usually presents between the ages of 30–50 years. These are slow growing tumours with an insidious onset of symptoms. The usual presentation is hormonal dysfunction or symptoms resulting from pressure effects such as visual field defects.

Medical management is important in secretory tumours. Transphenoidal surgery is the standard surgery for secretory tumours other than prolactinoma and macroadenoma producing pressure symptoms. The indication for radiotherapy is relative and usually indicated in tumour progression after surgery, uncontrolled hormone production, extensive residual tumour and invasion of the cavernous sinus. Radiotherapy is usually given as stereotactic fractionated radiotherapy or radiosurgery. Radiotherapy controls hypersecretion in 80% patients with acromegaly, 50–80% with Cushing’s disease and 33% with hyperprolactinaemia. In non-secretory tumours, surgery followed by radiotherapy results in a 20-year progression free interval of >90%. The long-term side effects of radiotherapy are hypopituitarism, increased risk of a second cancer (20-year risk of 2.4%), and increased risk of cerebrovascular death (relative risk 4.1).

Metastatic tumours of brain

Diagnosis

Contrast enhanced CT scan is usually diagnostic with more than half of the patients showing multiple metastases (Figure 16.7). The lesions are typically contrast enhancing and located in the junction between grey and white matter. MRI scan is useful in lesions in the posterior fossa, those with negative CT scans, those with suspected leptomeningeal disease and to confirm a solitary lesion if planning for surgical resection.

Prognosis

Untreated symptomatic patients have a median survival of 4–8 weeks. With steroids the survival is 8–12 weeks. A prognostic classification is shown in Table 16.3.

| Prognostic group* | Definition | Median survival (months) |

|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | Age less than 65 years, KPS ≥70, controlled primary disease and no extracranial metastases. | 7.1 |

| Class 2 | Neither class 1 nor 2 | 4.2 |

| Class 3 | KPS <70 | 2.3 |

* Based on RTOG RPA prognostic group. This is not applicable to chemosensitive tumours such as germ cell tumours, choriocarcinoma etc.

Treatment

Multiple brain metastases

There is no role for surgery in multiple metastases, except to relieve hydrocephalus. Patients with highly chemosensitive tumours (e.g. germ cell tumours, choriocarcinoma) are treated with initial chemotherapy followed by consolidation whole brain radiotherapy in some cases.

Single or solitary metastasis (on MRI) (Box 16.5)

Patients with inoperable tumours due to inaccessible locations may be considered for stereotactic radiosurgery followed by WBRT if they have a PS of 0–1, >1year disease-free interval and controlled systemic disease.

Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis

Infiltration of the leptomeninges by cancer commonly occurs with breast and lung cancer, melanoma, lymphoma and leukaemias. Clinical presentation can be with features of increased intracranial pressure, cranial nerve palsies or impaired higher function. Diagnosis is based on MRI scan (CT has a reduced sensitivity of 30% compared with 70% for MRI) and CSF examination. Typical findings on MRI are subarachnoid or parenchymal nodule (Figure 16.8) and sulcal/dural enhancement. Patients with good prognosis (limited disease, PS0–1, chemo-sensitive tumour and minimal neurologic deficit) are treated with intrathecal chemotherapy with radiotherapy to symptomatic sites and systemic chemotherapy. Median survival in untreated patients is 4–6 weeks, with prompt treatment median survival is around 6–8 months.

Spinal cord tumours

Spinal cord tumours can be either primary or secondary. Primary spinal cord tumours consist of 2–4% of all primary CNS tumours. Common spinal cord tumours are shown in Box 16.6.

Pain is the commonest presenting symptom. There will be varying degrees of spinal cord compression depending on the location of tumour. Evaluation includes a full neurological examination to assess the extent and level of neurological deficit. MRI is the imaging of choice. Intramedullary tumours may expand the cord and other imaging features are similar to that of corresponding tumours in the brain (Table 16.1).

Management

The definitive treatment is surgery. Early surgery is advocated to avoid further neurological damage. Maximal safe removal with the help of operative microscope and tools such as intraoperative ultrasound and cavitating ultrasonic aspirator is the norm. Indication for and dose of radiotherapy is as in Box 16.7. Radiotherapy is indicated for all intramedullary tumours except the following situations:

Box 16.7

Radiotherapy for intramedullary tumours

Extradural tumours treated according to the histologic type of the tumour.

Nieder C, Mehta MP, Jalali R. Combined radio- and chemotherapy of brain tumours in adult patients. Clin Oncol. 2009;21:515-524.

van den Bent MJ, Hegi ME, Stupp R. Recent developments in the use of chemotherapy in brain tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:582-588.

Noda SE, El-Jawahri A, Patel D, Lautenschlaeger T, Siedow M, Chakravarti A. Molecular advances of brain tumors in radiation oncology. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2009;19:171-178.

Van Meir EG, Hadjipanayis CG, Norden AD, Shu HK, Wen PY, Olson JJ. Exciting new advances in neuro-oncology: the avenue to a cure for malignant glioma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:166-193.

Soffietti R, Rudà R, Trevisan E. Brain metastases: current management and new developments. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;20:676-684.

Khuntia D, Brown P, Li J, Mehta MP. Whole-brain radiotherapy in the management of brain metastasis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1295-1304.

Traul DE, Shaffrey ME, Schiff D. Part I: spinal-cord neoplasms-intradural neoplasms. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:35-45.