Chapter 2 Central Nervous System Disorders

Lesions in the two components of the central nervous system (CNS) – the brain and the spinal cord – typically cause combinations of paresis, sensory loss, visual deficits, and neuropsychologic disorders (Box 2-1). Symptoms and signs of CNS disorders must be contrasted to those resulting from peripheral nervous system (PNS) and psychogenic disorders. In practice, neurologists tend to rely on the physical rather than mental status evaluation, thereby honoring the belief that “one Babinski sign is worth a thousand words.”

Box 2-1

Signs of Common Central Nervous System Lesions

Signs of Cerebral Hemisphere Lesions

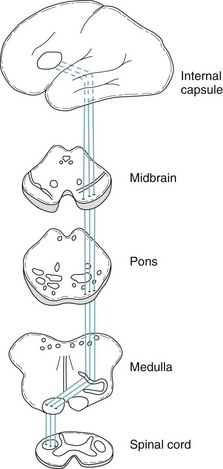

Of the various signs of cerebral hemisphere injury, contralateral hemiparesis (Box 2-2) – weakness of the lower face, trunk, arm, and leg opposite to the side of the lesion – is usually the most prominent. Damage to the corticospinal tract, also called the pyramidal tract (Fig. 2-1), in the cerebrum or brainstem before (above) the decussation of the pyramids causes contralateral hemiparesis. Damage to this tract after (below) the decussation of the pyramids, when it is in the spinal cord, causes ipsilateral arm and leg or only leg paresis. The extent of the paresis depends on the site of injury.

FIGURE 2-1 Each corticospinal tract originates in the cerebral cortex, passes through the internal capsule, and descends into the brainstem. It crosses in the pyramids, which are long protuberances on the inferior portion of the medulla, to descend in the spinal cord mostly as the lateral corticospinal tract. It terminates by forming a synapse with the anterior horn cells of the spinal cord, which give rise to peripheral nerves. The corticospinal tract is sometimes called the pyramidal tract because it crosses in the pyramids. The extrapyramidal tract, which modulates the corticospinal tract, originates in the basal ganglia and remains within the brain.

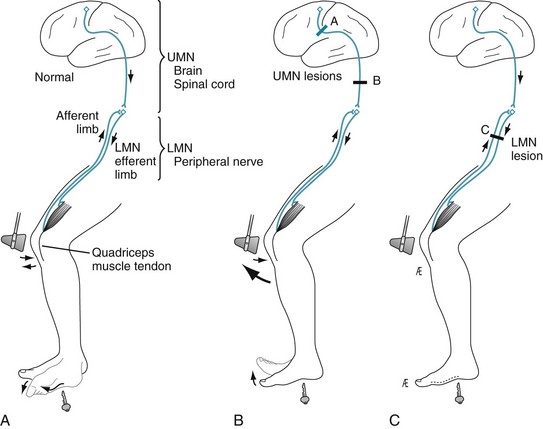

During the corticospinal tract’s entire path from the cerebral cortex to the anterior horn cells of the spinal cord, it is considered the upper motor neuron (UMN) (Fig. 2-2). The anterior horn cells, which are part of the PNS, are the beginning of the lower motor neuron (LMN). The division of the motor system into UMNs and LMNs is a basic tenet of clinical neurology.

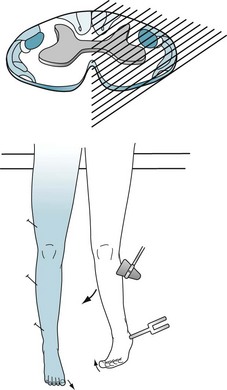

FIGURE 2-2 A, Normally, when physicians strike the quadriceps tendon with a percussion hammer, it elicits a deep tendon reflex (DTR). In addition, when they stroke the sole of the foot to elicit a plantar reflex, the big toe bends downward (flexes). B, When brain or spinal cord lesions involve the corticospinal tract and cause upper motor neuron (UMN) damage, the DTR is hyperactive: The muscle shows a brisker and more forceful contraction than usual, and adjacent muscle groups often also respond. In addition, with UMN damage, the plantar reflex is extensor (i.e., a Babinski sign is present). C, When peripheral nerve injury causes lower motor neuron (LMN) damage, the DTR is hypoactive and the plantar reflex is absent.

Cerebral lesions that damage the corticospinal tract are characterized by signs of UMN injury (Figs. 2-2 to 2-5):

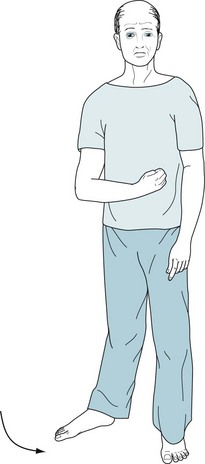

FIGURE 2-3 This patient with severe right hemiparesis typically shows weakness of the right arm, leg, and lower face. The right-sided facial weakness causes the widened palpebral fissure and flat nasolabial fold; however, the forehead muscles remain normal (see Chapter 4 regarding this discrepancy). The right arm is limp, and the elbow, wrist, and fingers take on a flexed position. The right hemiparesis also causes external rotation of the right leg and flexion of the hip and knee.

FIGURE 2-4 When the patient stands up, his weakened arm retains its flexed posture. His right leg remains externally rotated, but he can walk by swinging it in a circular path. This maneuver is effective but results in circumduction or a hemiparetic gait.

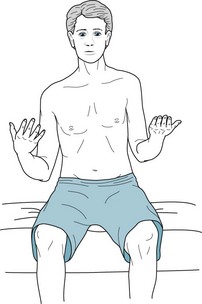

FIGURE 2-5 Mild hemiparesis may not be obvious. To exaggerate a subtle hemiparesis, the physician has asked this patient to extend both arms with his palms held upright, as though each outstretched hand were holding a water glass or both hands were supporting a pizza box (the “pizza test”). After a moment, a weakened arm slowly sinks (drifts), and the palm turns inward (pronates). The imaginary glass in the right hand would spill the water inward and the imaginary pizza would slide to the right. This arm drift and pronation represent a forme fruste of the posture seen with severe paresis (see Fig. 2-3).

Cerebral lesions are not the only cause of hemiparesis. Because the corticospinal tract has such a long course (see Fig. 2-1), lesions in the brainstem and spinal cord as well as the cerebrum may produce hemiparesis and other signs of UMN damage. Signs pointing to injury in various regions of the CNS can help identify the origin of hemiparesis, i.e., localize the lesion.

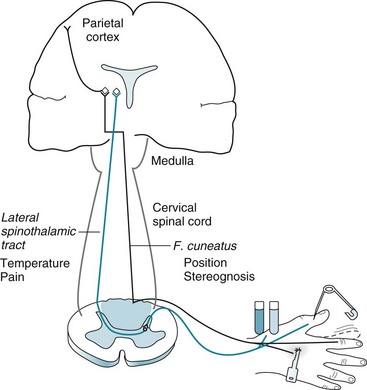

Another indication of a cerebral lesion is loss of certain sensory modalities over one-half of the body, i.e., hemisensory loss (Fig. 2-6). A patient with a cerebral lesion characteristically loses contralateral position sensation, two-point discrimination, and the ability to identify objects by touch (stereognosis). Loss of those modalities is often called a “cortical” sensory loss.

FIGURE 2-6 Peripheral nerves carry pain and temperature sensations to the spinal cord. After a synapse, these sensations cross and ascend in the contralateral lateral spinothalamic tract (blue) to terminate in the thalamus. From there, tracts relay the sensations to the limbic system, reticular activating system, and other brainstem regions as well as the cerebral cortex. In contrast, the peripheral nerves also carry position sense (tested by movement of the distal finger joint) and stereognosis (tested by tactile identification of common objects) to the ipsilateral fasciculus cuneatus and fasciculus gracilis, which together constitute the spinal cord’s posterior columns (light blue) (see Fig. 2-15). Unlike pain and temperature sensation, these sensations rise in ipsilateral tracts (black). They cross in the decussation of the medial lemniscus, which is in the medulla, synapse in the thalamus, and terminate in the parietal cortex. (To avoid spreading blood-borne illnesses, examiners should avoid using a pin when testing pain.)

Pain sensation, a “primary” sense, is initially received by the thalamus. Because the thalamus is just above the brainstem but below the cerebral cortex, pain perception is usually retained with cerebral lesions. For example, patients with cerebral infarctions may be unable to specify a painful area of the body, but will still feel the pain’s intensity and discomfort. Also, patients in intractable pain did not obtain relief when they underwent experimental surgical resection of the cerebral cortex. The other aspect of the thalamus’ role in sensing pain is seen when patients with thalamic infarctions develop spontaneous, disconcerting, burning pains over the contralateral body (see thalamic pain, Chapter 14).

Visual loss of the same half-field in each eye, homonymous hemianopsia (Fig. 2-7), is a characteristic sign of a contralateral cerebral lesion. Other equally characteristic visual losses are associated with lesions involving the eye, optic nerve, or optic tract (see Chapters 4 and 12). Because they would be situated far from the visual pathway, lesions in the brainstem, cerebellum, or spinal cord do not cause visual field loss.

FIGURE 2-7 In homonymous hemianopsia, the same half of the visual field is lost in each eye. In this case, a right homonymous hemianopsia is attributable to damage to the left cerebral hemisphere. This sketch portrays stippled or crosshatched visual field losses, as is customary, from the patient’s perspective (see Figs 4-1 and 12-9).

Another conspicuous sign of a cerebral hemisphere lesion is partial seizures (see Chapter 10). The major varieties of partial seizures – elementary, complex, and secondarily generalized – result from cerebral lesions. In fact, about 90% of partial complex seizures originate in the temporal lobe.

Signs of Damage of the Dominant, Nondominant, or Both Cerebral Hemispheres

Lesions of the dominant hemisphere may cause language impairment, aphasia, a prominent and frequently occurring neuropsychologic deficit (see Chapter 8). In addition to producing aphasia, dominant-hemisphere lesions typically produce an accompanying right hemiparesis because the corticospinal tract sits adjacent to the language centers (see Fig. 8-1).

When the nondominant parietal lobe is injured, patients often have one or more characteristic neuropsychologic deficits that comprise the “nondominant syndrome” as well as left-sided hemiparesis and homonymous hemianopsia. For example, patients may neglect or ignore left-sided visual and tactile stimuli (hemi-inattention; see Chapter 8). Patients often fail to use their left arm and leg more because they neglect their limbs than because of paresis. When they have left hemiparesis, patients may not even perceive their deficit (anosognosia). Many patients lose their ability to arrange matchsticks into certain patterns or copy simple forms (constructional apraxia; Fig. 2-8).

FIGURE 2-8 With constructional apraxia from a right parietal lobe infarction, a 68-year-old woman was hardly able to complete a circle (top figure). She could not draw a square on request (second highest figure) or even copy one (third highest figure). She spontaneously tried to draw a circle and began to retrace it (bottom figure). Her constructional apraxia consists of the rotation of the forms, perseveration of certain lines, and the incompleteness of the second and lowest figures. In addition, the figures tend toward the right-hand side of the page, which indicates that she has neglect of the left-hand side of the page, i.e., left hemi-inattention.

All signs discussed so far are referable to unilateral cerebral hemisphere damage. Bilateral cerebral hemisphere damage produces several important disturbances. One of them, pseudobulbar palsy, best known for producing emotional lability, results from bilateral corticobulbar tract damage (see Chapter 4). The corticobulbar tract, like its counterpart the corticospinal tract, originates in the motor cortex of the posterior portion of the frontal lobe. It innervates the brainstem motor nuclei that in turn innervate the head and neck muscles. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) and many illnesses, including cerebral infarctions (strokes) and frontotemporal dementia (see Chapter 7), are apt to strike the corticobulbar tract and the surrounding frontal lobes and thereby cause pseudobulbar palsy.

Damage of both cerebral hemispheres – from large or multiple discrete lesions, degenerative diseases, or metabolic abnormalities – also causes dementia (see Chapter 7). In addition, because CNS damage that causes dementia must be extensive and severe, it usually also produces at least subtle physical neurologic findings, such as hyperactive DTRs, Babinski signs, mild gait impairment, and frontal lobe release reflexes. Many illnesses that cause dementia, such as Alzheimer disease, do not cause overt findings, such as hemiparesis. In acute care hospitals, the five conditions most likely to cause discrete unilateral or bilateral cerebral lesions are strokes, primary or metastatic brain tumors, TBI, complications of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and multiple sclerosis (MS). (Section 2 offers detailed discussions of these conditions.)

Signs of Basal Ganglia Lesions

The basal ganglia, located subcortically in the cerebrum, are composed of the globus pallidus, caudate, and putamen (all together, the striatum); substantia nigra; and subthalamic nucleus (corpus of Luysii) (see Fig. 18-1). They give rise to the extrapyramidal tract, which modulates the corticospinal (pyramidal) tract. The extrapyramidal tract controls muscle tone, regulates motor activity, and generates postural reflexes. Its efferent fibers play on the cerebral cortex, thalamus, and other CNS structures. Because its efferent fibers are confined to the brain, the extrapyramidal tract does not act directly on the spinal cord or LMNs.

Signs of basal ganglia disorders include a group of fascinating, often dramatic, involuntary movement disorders (see Chapter 18):

• Parkinsonism is the combination of resting tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia (slowness of movement) or akinesia (absence of movement), and postural abnormalities. Minor features include micrographia and festinating gait (Table 2-1). Parkinsonism usually results from substantia nigra degeneration (Parkinson disease and related illnesses), dopamine-blocking antipsychotic medications, or toxins.

• Athetosis is the slow, continuous, writhing movement of the fingers, hands, face, and throat. Kernicterus or other perinatal basal ganglia injury usually causes it.

• Chorea is intermittent, randomly located jerking of limbs and the trunk. The best-known example occurs in Huntington disease (previously called “Huntington chorea”), in which the caudate nuclei characteristically atrophy.

• Hemiballismus is the intermittent flinging of the arm and leg on one side of the body. It is classically associated with small infarctions of the contralateral subthalamic nucleus, but similar lesions in other basal ganglia may be responsible.

TABLE 2-1 Gait Abnormalities Associated with Neurologic Disorders

| Gait | Associated Illness | Figure |

|---|---|---|

| Apraxic | Normal pressure hydrocephalus | 7-10 |

| Astasia-Abasia | Psychogenic disorders | 3-4 |

| Ataxic | Cerebellar damage | 2-13 |

| Festinating (marche à petits pas) | Parkinson disease | 18-9 |

| Hemiparetic/hemiplegic | Strokes, Congenital injury (cerebral palsy) | |

| Circumduction | 2-4 | |

| Spastic hemiparesis | 13-4 | |

| Diplegic | Congenital injury (cerebral palsy) | 13-3 |

| Steppage | Tabes dorsalis (CNS syphilis) | 2-20 |

| Peripheral neuropathies | ||

| Waddling | Duchenne dystrophy and other myopathies | 6-4 |

In general, when damage is restricted to the extrapyramidal tract, as in many cases of hemiballismus and athetosis, patients have no paresis, DTR abnormalities, or Babinski signs – signs of corticospinal (pyramidal) tract damage. More importantly, in many of these conditions, patients have no cognitive impairment or other neuropsychologic abnormality. On the other hand, several involuntary movement disorders, such as Huntington disease, Wilson disease, and advanced Parkinson disease (see Box 18-4), affect the cerebrum as well as the basal ganglia. In these illnesses, dementia, depression, and psychosis are frequent comorbidities.

Signs of Brainstem Lesions

The brainstem contains, among a multitude of structures, the cranial nerve nuclei, the corticospinal tracts and other “long tracts” that travel between the cerebral hemispheres and the limbs, and cerebellar afferent (inflow) and efferent (outflow) tracts. Combinations of cranial nerve and long tract signs indicate the presence and location of a brainstem lesion. The localization should be supported by the absence of signs of cerebral injury, such as visual field cuts and neuropsychologic deficits. For example, brainstem injuries cause diplopia (double vision) because of cranial nerve impairment, but visual acuity and visual fields remain normal because the visual pathways, which pass from the optic chiasm to the cerebral hemispheres, do not travel within the brainstem (see Fig. 4-1). Similarly, a right hemiparesis associated with a left third cranial nerve palsy indicates that the lesion is in the brainstem and that neither aphasia nor dementia will be present.

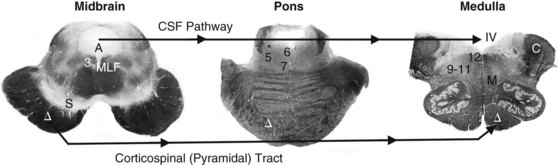

Several brainstem syndromes illustrate critical anatomic relationships, such as the location of the cranial nerve nuclei or the course of the corticospinal tract; however, none of them involves neuropsychologic abnormalities. Although each syndrome has an eponym, for practical purposes it is only necessary to identify the clinical findings and, if appropriate, attribute them to a lesion in one of the three major divisions of the brainstem: midbrain, pons, or medulla (Fig. 2-9). Whatever the localization, most brainstem lesions consist of an occlusion of a small branch of the basilar or vertebral arteries.

FIGURE 2-9 Myelin stains of the three main divisions of the brainstem – midbrain, pons, and medulla – show several clinically important tracts, the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathway, and motor nuclei of the cranial nerves.

Midbrain, The midbrain (Greek, meso, middle) is identifiable by its distinctive silhouette and gently curved (pale, unstained in this preparation) substantia nigra (S). The aqueduct of Sylvius (A) is surrounded by the periaqueductal gray matter. Below the aqueduct, near the midline, lie the oculomotor (3) and trochlear (not pictured) cranial nerve nuclei. The nearby medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF), which ascends from the pons, terminates in the oculomotor nuclei. The large, deeply stained cerebral peduncle, inferior to the substantia nigra, contains the corticospinal (pyramidal [Δ]) tract. Originating in the cerebral cortex, the corticospinal tract (Δ) descends ipsilaterally through the midbrain, pons, and medulla until it crosses in the medulla’s pyramids to continue within the contralateral spinal cord. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flows downward from the lateral ventricles through the aqueduct of Sylvius into the fourth ventricle (IV), which overlies the lower pons and medulla. CSF exits from the fourth ventricle into the subarachnoid space. (Also see a functional drawing [Fig. 4-5], computer-generated rendition [Fig. 18-2], and sketch [Fig. 21-1].)

Pons, The pons (Latin, bridge) houses the trigeminal motor division (5), abducens (6), facial (7), and acoustic/vestibular (not shown) cranial nerve nuclei and, inferior and lateral to the fourth ventricle, the locus ceruleus (*). In addition to containing the descending corticospinal tract, the basilar portion of the pons, the “basis pontis,” contains large criss-crossing cerebellar tracts. (Also see a functional drawing [Fig. 4-7] and an idealized sketch [Fig. 21-2].)

Medulla, The medulla (Latin, marrow), readily identifiable by the pair of unstained scallop-shaped inferior olivary nuclei, includes the cerebellar peduncles (C), which contain afferent and efferent cerebellar tracts; the corticospinal tract (Δ); and the floor of the fourth ventricle (IV). It also contains the decussation of the medial lemniscus (M), the nuclei for cranial nerves 9–11 grouped laterally and 12 situated medially, and the trigeminal sensory nucleus (not pictured) that descends from the pons to the cervical–medullary junction. (Also see a functional drawing [Fig. 2-10].)

In the midbrain, where the oculomotor (third cranial) nerve passes through the descending corticospinal tract, a single small infarction can damage both pathways. Patients with oculomotor nerve paralysis and contralateral hemiparesis typically have a midbrain lesion ipsilateral to the paretic eye (see Fig. 4-9).

Patients with abducens (sixth cranial) nerve paralysis and contralateral hemiparesis likewise have a pons lesion ipsilateral to the paretic eye (see Fig. 4-11).

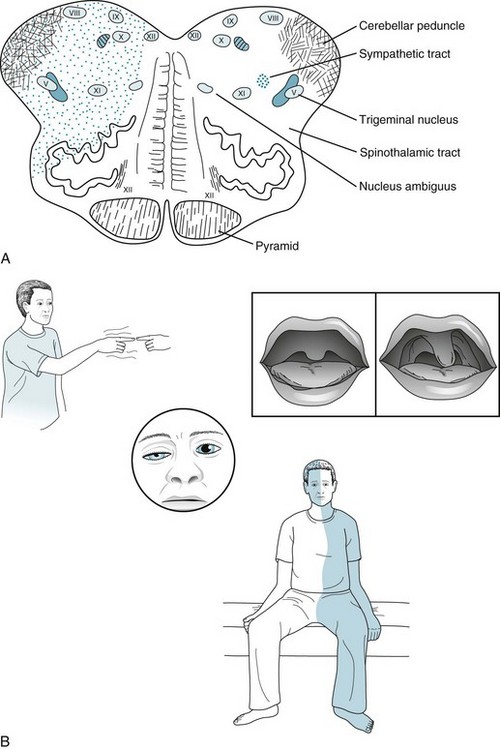

Lateral medullary infarctions create a classic but complex picture. Patients have dysarthria because of paralysis of the ipsilateral palate from damage to cranial nerves IX through XI; ipsilateral facial numbness (hypalgesia) (Greek, decreased sensitivity to pain) because of damage to cranial nerve V, with contralateral anesthesia of the body (alternating hypalgesia) because of ascending spinothalamic tract damage; and ipsilateral ataxia because of ipsilateral cerebellar dysfunction. In other words, the lateral medullary syndrome consists of damage to three nuclei (V, VII, and IX–XI) and three white-matter tracts (spinothalamic, sympathetic, and inferior cerebellar). Although the lateral medullary syndrome commonly occurs and provides an excellent example of clinical–pathologic correlation, physicians need not recall all of its pathology or clinical features; however, they should know that lower cranial nerve palsies accompanied by alternating hypalgesia, without cognitive impairment or limb paresis, characterize a lower brainstem lesion (Fig. 2-10).

FIGURE 2-10 A, An occlusion of the right posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) or its parent artery, the right vertebral artery, has caused an infarction of the lateral portion of the right medulla. This infarction damages important structures: the cerebellar peduncle, the trigeminal nerve (V) sensory tract, the spinothalamic tract (which arose from the contralateral side of the body), the nucleus ambiguus (cranial nerves IX–XI motor nuclei), and poorly delineated sympathetic fibers. However, this infarction spares medial structures: the corticospinal tract, medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF), and hypoglossal nerve (XII) nucleus. B, This patient has a right-sided Wallenberg syndrome. He has a right-sided Horner syndrome (ptosis and miosis) because of damage to the sympathetic fibers (see Fig. 12-15). He has right-sided ataxia because of damage to the ipsilateral cerebellar tracts. He has an alternating hypalgesia: diminished pain sensation on the right side of his face, accompanied by loss of pain sensation on the left trunk and extremities. Finally, he has hoarseness and paresis of the right soft palate because of damage to the right nucleus ambiguus. Because of the right-sided palate weakness, the palate deviates upward toward his left on voluntary phonation (saying “ah”) or in response to the gag reflex.

Although these particular brainstem syndromes are distinctive, the most frequently observed sign of brainstem dysfunction is nystagmus (repetitive jerk-like eye movements, usually simultaneously, of both eyes). Resulting from any type of injury of the brainstem’s large vestibular nuclei, nystagmus can be a manifestation of various disorders, including intoxication with alcohol, phenytoin (Dilantin), phencyclidine (PCP), or barbiturates; ischemia of the vertebrobasilar artery system; MS; Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome; or viral labyrinthitis. Among individuals who have ingested PCP, coarse vertical and horizontal (three-directional) nystagmus characteristically accompanies an agitated delirium and markedly reduced sensitivity to pain and cold temperatures. Unilateral nystagmus may be a component of internuclear ophthalmoplegia, a disorder of ocular motility in which the brainstem’s medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF) is damaged. The usual cause is MS or a small infarction (see Chapters 4 and 15).

Signs of Cerebellar Lesions

Although several studies utilizing sophisticated imaging techniques and neuropsychologic testing suggest that the cerebellum affects cognition and emotion, it does not play a discernible role in these functions in everyday endeavors. For example, unless cerebellar lesions simultaneously involve the cerebrum, they do not lead to dementia, language impairment, or other cognitive impairment. A good example is the normal intellect of children and young adults despite having undergone resection of a cerebellar hemisphere for removal of an astrocytoma (see Chapter 19).

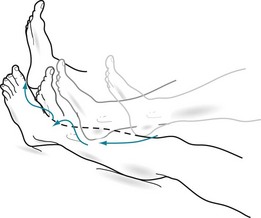

For practical purposes, neurologists assess cerebellar function in tests of coordinated motor function. A characteristic sign of cerebellar dysfunction is intention tremor, demonstrable on the finger-to-nose (Fig. 2-11) and heel-to-shin (Fig. 2-12) tests. This tremor is evident when the patient moves willfully but absent when the patient rests. In a classic contrast, Parkinson disease causes a resting tremor that is present when the patient sits quietly and reduced or even abolished when the patient moves (see Chapter 18). Physicians should not confuse the neurologic term “intention tremor” with “intentional tremor,” which would be a self-induced or psychogenic tremor.

FIGURE 2-11 This young man has a multiple sclerosis plaque in the right cerebellar hemisphere. During the finger-to-nose test, his right index finger touches his nose and then the examiner’s finger by following a coarse, irregular path. The oscillation in his arm’s movement is an intention tremor, and the irregularity in the rhythm is dysmetria.

FIGURE 2-12 In the heel-to-shin test, the patient with the right-sided cerebellar lesion in Figure 2-11 displays limb ataxia as his right heel wobbles when he pushes it along the crest of his left shin.

Damage to either the entire cerebellum or the vermis alone causes incoordination of the trunk (truncal ataxia). This manifestation of cerebellar damage forces patients to place their feet widely apart when standing and leads to a lurching, unsteady, and wide-based pattern of walking (gait ataxia) (Table 2-1 and Fig. 2-13). A common example is the staggering and reeling of people intoxicated by alcohol. In addition, such cerebellar damage prevents people from walking heel-to-toe, i.e., performing the “tandem gait” test.

FIGURE 2-13 This man, a chronic alcoholic, has developed diffuse cerebellar degeneration. He has a typical ataxic gait: broad-based, unsteady, and uncoordinated. To steady his stance, he stands with his feet apart and pointed outward.

Extensive damage of the cerebellum causes scanning speech, a variety of dysarthria. Scanning speech, which reflects incoordination of speech production, is characterized by poor modulation, irregular cadence, and inability to separate adjacent sounds. Physicians should easily be able to distinguish dysarthria – whether caused by cerebellar injury, bulbar or pseudobulbar palsy, or other neurologic disorder – from aphasia (see Chapter 8).

Illnesses that Affect the Cerebellum

The conditions responsible for most cerebral lesions – strokes, tumors, TBI, AIDS, and MS – also cause most cerebellar lesions. In addition, the cerebellum seems to be particularly sensitive to a wide range of toxic and metabolic products. Pharmacologic as well as industrial items damage the cerebellum primarily or exclusively. For example, phenytoin, chemotherapy agents, and lithium cause transient or, particularly in the case of lithium intoxication, permanent cerebellar damage. Similarly, industrial intoxicants, such as toluene (see Chapters 5 and 15) and organic mercury, cause cerebellar damage. Nutritional deprivations, such as vitamin E and alcohol-induced thiamine deficiency, may be responsible.

Through a mechanism entirely different than intoxication, antibodies directed at a systemic malignancy destructively cross-react with cerebellar tissue. The most common example of such an unintended consequence of the immune system’s response to a malignancy is the cerebellar degeneration associated with lung cancer. This paraneoplastic syndrome (see Chapter 19) and others are akin to molecular mimicry underlying Sydenham chorea and pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS) (see Chapter 18).

Genetic abnormalities underlie numerous cerebellar illnesses. Most of them follow classic autosomal dominant or recessive patterns. Several result from unstable trinucleotide repeats in chromosomal DNA or abnormalities in mitochondrial DNA (see Chapter 6 and Appendix 3). For example, excessive trinucleotide repeats give rise to Friedreich ataxia, the most common hereditary ataxia in the United States and Europe. Some hereditary ataxias cause cognitive impairment and characteristic nonneurologic manifestations, such as kyphosis, cardiomyopathy, and pes cavus (Fig. 2-14), in addition to cerebellar signs.

FIGURE 2-14 The pes cavus foot deformity consists of a high arch, elevation of the dorsum, and retraction of the first metatarsal. When pes cavus occurs in families with childhood-onset ataxia and posterior column sensory deficits, it is virtually pathognomonic of Friedreich ataxia.

One large, heterogeneous group of genetic illnesses, the spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs), damages the spinal cord, the cerebellum, and its major connections. In general, the SCAs consist of progressively severe gait ataxia, scanning speech, and incoordination of hand and finger movements. Depending on the SCA variety, patients may also show cognitive impairment, sensory loss, spasticity, or ocular motility problems. Even though their manifestations greatly differ, several SCA varieties, like Huntington disease (see Chapter 18), result from excessive trinucleotide repeats. Because excessive trinucleotide repeats lead to excessive synthesis of polyglutamine, neurologists refer to all these illnesses as polyglutamine diseases.

Signs of Spinal Cord Lesions

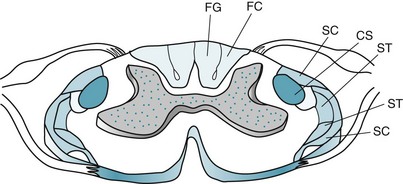

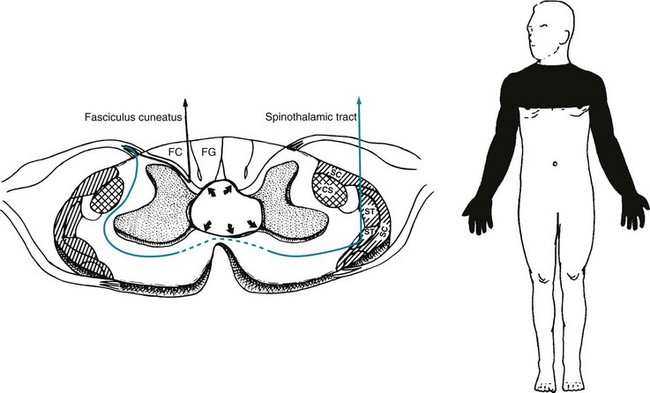

The spinal cord’s gray matter, a broad H-shaped structure, consists largely of neurons that transmit nerve impulses in a horizontal plane. It occupies the center of the spinal cord. The spinal cord’s white matter, composed of myelinated tracts that convey information in a vertical direction, surrounds the central gray matter (Fig. 2-15). This pattern – gray matter on the inside with white outside – is opposite to that of the cerebrum. Because interruption of the myelinated tracts causes most of the signs, neurologists call spinal cord injury “myelopathy.”

FIGURE 2-15 In this sketch of the spinal cord, the centrally located gray matter is stippled. The surrounding white matter contains myelin-coated ascending and descending tracts. Clinically important ascending tracts are the spinocerebellar tracts (SC), the lateral spinothalamic tract (ST), and the posterior column [fasciculus cuneatus (FC), from the upper limbs, and fasciculus gracilis (FG), from the lower limbs]. The most important descending tract is the lateral corticospinal (CS) tract.

The major descending pathway, entirely motor, is the lateral corticospinal tract.

The major ascending pathways, entirely sensory, include the following:

• Posterior columns, comprised of the fasciculi cuneatus and gracilis, carry position and vibration sensations to the thalamus.

• Lateral spinothalamic tracts carry temperature and pain sensations to the thalamus.

• Anterior spinothalamic tracts carry light touch sensation to the thalamus.

• Spinocerebellar tracts carry joint position and movement sensations to the cerebellum.

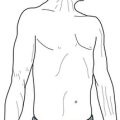

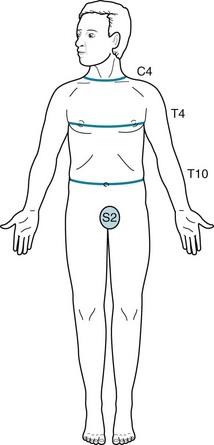

When a spinal cord injury is discrete and complete, such as a complete transection, the lesion’s location – cervical, thoracic, or lumbosacral – determines the nature and distribution of the motor and sensory deficits. Cervical spinal cord transection, for example, blocks all motor impulses from descending and sensory perception from arising through the neck. This lesion will cause paralysis of the arms and legs (quadriparesis) and, after 1–2 weeks, spasticity, hyperactive DTRs, and Babinski signs. In addition, it will prevent the perception of all limb, trunk, and bladder sensation. Similarly, a mid thoracic spinal cord transection will cause paralysis of the legs (paraparesis) with similar reflex changes, and sensory loss of the trunk below the nipples and the legs (Fig. 2-16). In general, all spinal cord injuries disrupt bladder control and sexual function, which rely on delicate, intricate systems (see Chapter 16).

FIGURE 2-16 In a patient with a spinal cord injury, the “level” of hypalgesia indicates the site of the damage. The clinical landmarks are C4, T4, and T10. C4 injuries cause hypalgesia below the neck; T4 injuries, hypalgesia below the nipples; T10 injuries, hypalgesia below the umbilicus.

In a variation of the complete spinal cord lesion, when a lesion transects only the lateral half of the spinal cord, it results in the Brown-Séquard syndrome (Fig. 2-17). The defining features of this classic syndrome are ipsilateral paralysis of limb(s) from corticospinal tract damage and loss of vibration and proprioception from dorsal column damage combined with loss of temperature and pain (hypalgesia) sensation in the opposite limb(s) from lateral spinothalamic tract damage. In the vernacular of neurology, one leg is weak and the other is numb.

FIGURE 2-17 In this case of hemitransection of the spinal cord (Brown-Séquard syndrome), the left side of the thoracic spinal cord has been transected, as by a knife wound. Injury to the patient’s left lateral corticospinal tract results in the combination of left-sided leg paresis, hyperactive deep tendon reflexes, and a Babinski sign; injury to the left posterior column results in impairment of left leg vibration and position sense. Most strikingly, injury to the left spinothalamic tract causes loss of temperature and pain sensation in the right leg. The loss of pain sensation contralateral to the paresis is the signature of the Brown-Séquard syndrome.

Another motor impairment attributable to spinal cord damage, whether structural or nonstructural, is spasticity. The pathologically increased muscle tone often creates more disability than the accompanying paresis. For example, because it causes the legs to be straight, extended, and unyielding, patients tend to walk on their toes (see Fig. 13-3). Similarly, spasticity greatly limits the usefulness of patients’ hands and fingers.

Conditions that Affect the Spinal Cord

Discrete Lesions

The entire spinal cord is vulnerable to penetrating wounds, such as gunshots and stabbings; tumors of the lung, breast, and other organs that metastasize to the spinal cord (see Fig. 19-5); degenerative spine disease, such as cervical spondylosis, that narrows the spinal canal enough to compress the spinal cord (see Fig. 5-10); and MS and its variant, neuromyelitis optica (see Chapter 15). Nevertheless, whatever its etiology, the lesion’s location determines the deficits.

A lesion that often affects only the cervical spinal cord consists of an elongated cavity, syringomyelia or a syrinx (Greek, syrinx, pipe or tube + myelos marrow), adjacent to the central canal, which is the thin tube running vertically within the gray matter. The syrinx usually develops, for unclear reasons, in adolescents. Traumatic intraspinal bleeding may cause a variety of syrinx, a hematomyelia. The clinical findings of a syrinx or hematomyelia, which allow a diagnosis by neurologic examination, reflect its underlying neuroanatomy (Fig. 2-18). As the cavity expands, its pressure rips apart the lateral spinothalamic tract fibers as they cross from one to the other side of the spinal cord. It also compresses on the anterior horn cells of the anterior gray matter. The expansion not only causes neck pain, but a striking loss in the arms and hands of sensation of pain and temperature, muscle bulk, and DTRs. Because the sensory loss is restricted to patients’ shoulders and arms, neurologists frequently describe it as cape-like or suspended. Moreover, the sensory loss is characteristically restricted to loss of pain and temperature sensation because the posterior columns, merely displaced, remain functional.

FIGURE 2-18 Left, A syringomyelia (syrinx) is an elongated cavity in the spinal cord. Its expansion disrupts the lateral spinothalamic tract (ST) as it crosses and compresses the anterior horn cells of the gray matter. Unless the syrinx is large, it only presses on the posterior columns and corticospinal (CS) tracts and does not impair their function. Right, The classic finding is a suspended sensory loss (loss of only pain and temperature sensation in the arms and upper chest [in this case, C4–T4]) that is accompanied by weakness, atrophy, and deep tendon reflex loss in the arms. SC, spinocerebellar tract; FC, fasciculus cuneatus; FG, fasciculus gracilis.

Neurologic Illnesses

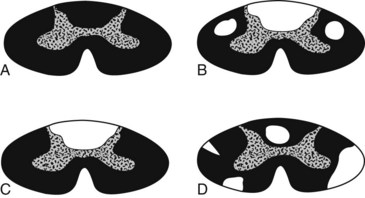

Several illnesses damage only specific spinal cord tracts (Fig. 2-19). The posterior columns – fasciculus gracilis and fasciculus cuneatus – seem particularly vulnerable. For example, tabes dorsalis (syphilis), combined system disease (B12 deficiency; see Chapter 5), Friedreich ataxia, and the SCAs each damages the posterior columns alone or in combination with other tracts. In these conditions, impairment of the posterior columns leads to a loss of position sense that prevents patients from being able to stand with their eyes closed (Romberg sign). When they walk, this sensory loss produces a steppage gait (Fig. 2-20).

FIGURE 2-19 A, A standard spinal cord histologic preparation stains normal myelin (white matter) black and leaves the central H-shaped column gray. B, In combined system disease (vitamin B12 deficiency), posterior column and corticospinal tract damage causes their demyelination and lack of stain. C, In tabes dorsalis (tertiary syphilis), damage to the posterior column leaves them unstained. D, Multiple sclerosis leads to asymmetric, irregular, demyelinated unstained plaques.

FIGURE 2-20 The steppage gait consists of each knee being excessively raised when walking. This maneuver compensates for a loss of position sense by elevating the feet to ensure that they will clear the ground, stairs, and other obstacles. It is a classic sign of posterior column spinal cord damage from tabes dorsalis. However, peripheral neuropathies more commonly impair position sense and lead to this gait abnormality.

Several toxic-metabolic disorders – some associated with substance abuse – damage the spinal cord. For example, nitrous oxide, a gaseous anesthetic, typically when inhaled continually as a drug of abuse by thrill-seeking dentists, causes a pronounced myelopathy by inactivating B12 (see Chapter 5). Copper deficiency, often from excess consumption of zinc by food faddists or inadvertently ingested with excess denture cream, leads to myelopathy. Also, unless physicians closely monitor and replace vitamins and nutrients following gastric bypass surgery, patients are prone to develop myelopathy for up to several years after the surgery.