Cells and Cellular Activities of the Immune System

Granulocytes and Mononuclear Cells

At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader should be able to:

• Describe the general functions of granulocytes, monocytes-macrophages, and lymphocytes and plasma cells as components of the immune system.

• Explain the process of phagocytosis.

• Describe the composition and function of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs).

• Discuss the role of monocytes and macrophages in cellular immunity.

• Define and compare acute inflammation and sepsis.

• Briefly describe cell surface receptors.

• Name and compare the signs and symptoms of disorders of neutrophil function.

• Compare the signs and symptoms of two monocyte or macrophage disorders.

• Describe states involving the leukocyte integrins.

• Analyze case studies related to defects of neutrophils.

• Correctly answer case study related multiple choice questions.

• Be prepared to participate in a discussion of critical thinking questions.

• Describe the principal reporting of results, sources of error, clinical applications, and limitations of a phagocytic engulfment test.

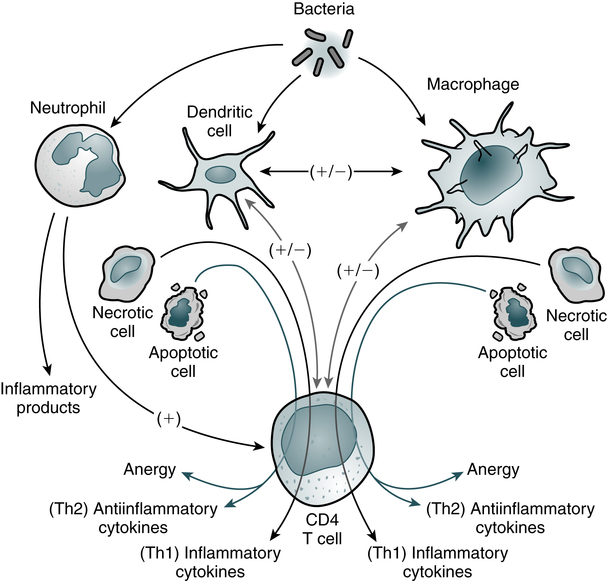

The entire leukocytic cell system is designed to defend the body against disease. Each cell type has a unique function and behaves independently and, in many cases, in cooperation with other cell types. Leukocytes can be functionally divided into the general categories of granulocyte, monocyte-macrophage, and lymphocyte–plasma cell. The primary phagocytic cells are the polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) leukocytes and the mononuclear monocytes-macrophages. The response of the body to pathogens involves cross-talk among many immune cells, including macrophages, dendritic cells, and CD4 T cells (Fig. 3-1). The lymphocytes participate in body defenses primarily through the recognition of foreign antigens and production of antibody. Plasma cells are antibody-synthesizing cells.

Origin and Development of Blood Cells

1. The first blood cells are primitive red blood cells (RBCs; erythroblasts) formed in the islets of the yolk sac during the first 2 to 8 weeks of life.

2. Gradually, the liver and spleen replace the yolk sac as the sites of blood cell development. By the second month of gestation, the liver becomes the major site of hematopoiesis, and granular types of leukocytes have made their initial appearance. The liver and spleen predominate from about 2 to 5 months of fetal life.

3. In the fourth month of gestation, bone marrow begins to produce blood cells. After the fifth fetal month, bone marrow begins to assume its ultimate role as the primary site of hematopoiesis.

Granulocytic Cells

Neutrophils

Neutrophilic leukocytes, particularly the polymorphonuclear (PMN) type (see Color Plate 4), provide an effective host defense against bacterial and fungal infections. The antimicrobial function of PMNs is essential in the innate immune response. Although the monocytes-macrophages and other granulocytes are also phagocytic cells, the PMN is the principal leukocyte associated with phagocytosis and a localized inflammatory response. The formation of an inflammatory exudate (pus), which develops rapidly in an inflammatory response, is composed primarily of neutrophils and monocytes.

The granules of segmented neutrophils contain various antibacterial substances (Table 3-1). During the phagocytic process, the powerful antimicrobial enzymes that are released also disrupt the integrity of the cell itself. Neutrophils are also steadily lost to the respiratory, gastrointestinal (GI), and urinary systems, where they participate in generalized phagocytic activities. An alternate route for the removal of neutrophils from the circulation is phagocytosis by cells of the mononuclear phagocyte system.

Table 3-1

Function and Types of Granules in Neutrophils

| Function | Azurophilic (Primary) Granules | Specific (Secondary) Granules |

| Microbicidal | Myeloperoxidase | Cytochrome b558 and other respiratory burst components |

| Lysozyme | Lysozyme | |

| Elastase | Lactoferrin | |

| Defensins | ||

| Cathepsin G | ||

| Proteinase-3 | ||

| Bacterial permeability-increasing protein (BPI) | ||

| Cell migration | Collagenase | |

| CD11b–CD18 (CR-3) | ||

| N-formulated peptides (e.g., N-formyl-methionyl-leucylphenylalanine receptor [FMLP-R]) |

Adapted from Peakman M, Vergani D: Basic and clinical immunology, ed 2, Edinburgh, 2009, Churchill Livingstone, p 24.

Eosinophils and Basophils

Eosinophils

The eosinophil (see Color Plate 5) is considered to be a homeostatic regulator of inflammation. Functionally, this means that the eosinophil attempts to suppress an inflammatory reaction to prevent the excessive spread of the inflammation. The eosinophil may also play a role in the host defense mechanism because of its ability to kill certain parasites.

Basophils

Basophils (see Color Plate 6) have high concentrations of heparin and histamine in their granules, which play an important role in acute, systemic, hypersensitivity reactions (see Chapter 26). Degranulation occurs when an antigen such as pollen binds to two adjacent immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibody molecules located on the surface of mast cells. The events resulting from the release of the contents of these basophilic granules include increased vascular permeability, smooth muscle spasm, and vasodilation. If severe, this reaction can result in anaphylactic shock.

Process of Phagocytosis

Phagocytosis can be divided into six stages—chemotaxis, adherence, engulfment, phagosome formation, fusion, and digestion and destruction (Fig. 3-2). The physical occurrence of damage to tissues, by trauma or microbial multiplication, releases substances such as activated complement components and products of infection to initiate phagocytosis.

Chemotaxis

• Fc receptor—binds the Fc portion of antibody molecules, chiefly immunoglobulin G (IgG). The IgG attaches to the organism through its Fab site.

• Complement receptor—the third component of complement, C3, also binds to organisms and then attaches to the complement receptor.

1. Antibody attached to the surface of a bacterium minimally binds the Fc phagocyte receptor.

2. Complement C3b is attached to the surface of the bacterium and binds loosely to the phagocyte C3b receptor.

3. Both antibody and C3b are attached to the surface of the bacterium and bound tightly to the phagocyte, allowing greater opportunity for the phagocyte to engulf the bacterium.

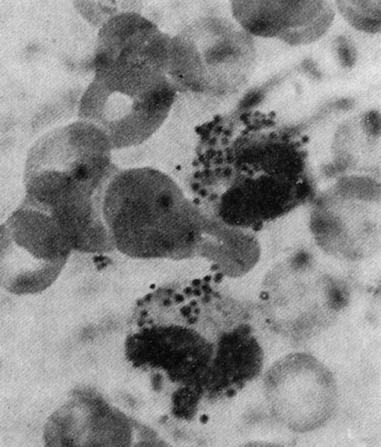

Engulfment

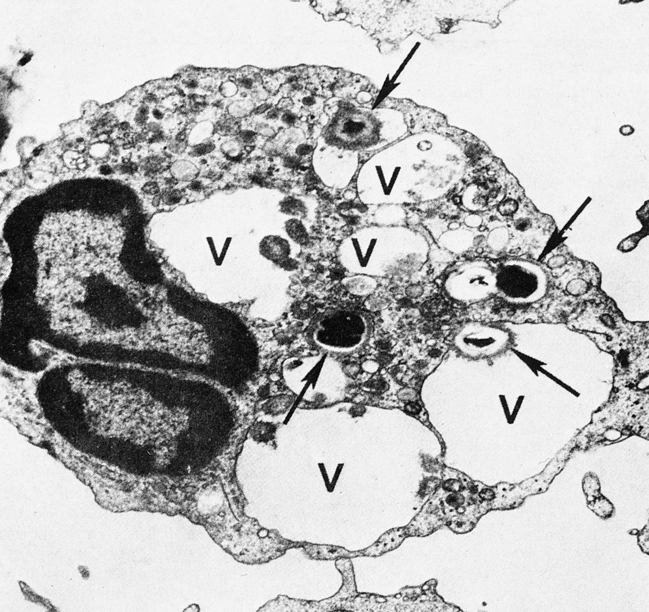

On reaching the site of infection, phagocytes engulf and destroy the foreign matter (Fig. 3-3). Eosinophils can also undergo this process, except that they kill parasites. After the phagocytic cells have arrived at the site of injury, the bacteria can be engulfed through active membrane invagination. Pseudopodia are extended around the pathogen, pulled by interactions between the Fc receptors and Fc antibody portions on the opsonized bacterium. Pseudopodia meet and fuse, thereby internalizing the bacterium and enclosing it in a phagocytic vacuole, or phagosome.

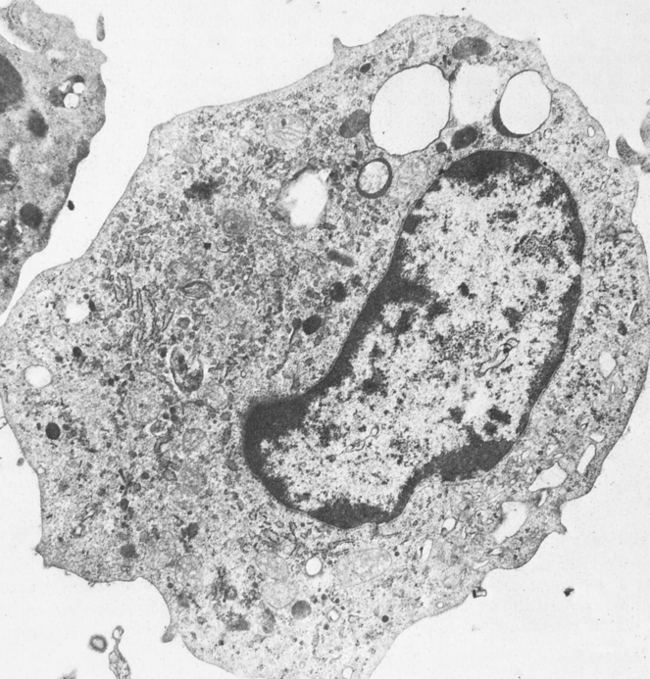

Monocytes-Macrophages

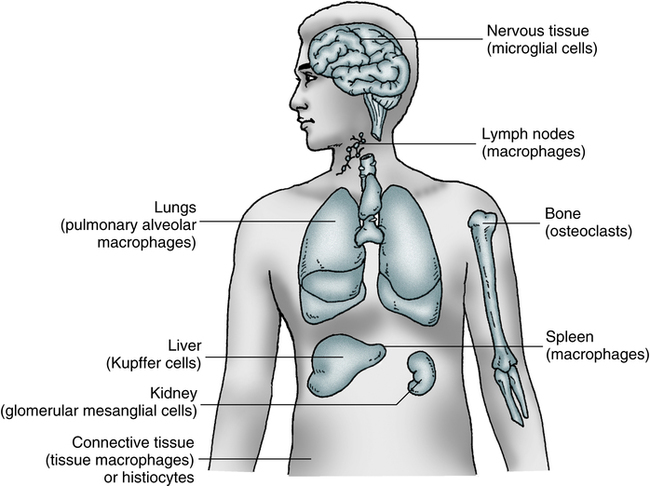

Mononuclear Phagocyte System

The macrophage (Fig. 3-4) and its precursors are widely distributed throughout the body. These cells constitute a physiologic system, the mononuclear phagocyte system (previously referred to as the reticuloendothelial system), which includes promonocytes and their precursors in the bone marrow, monocytes in the circulating blood, and macrophages in tissues. This collection of cells is considered to be a system because of the common origin, similar morphology, and shared functions, including rapid phagocytosis mediated by receptors for IgG and the major fragment of C3.

Macrophages and monocytes (see Color Plate 7) migrate freely into the tissues from the blood to replenish and reinforce the macrophage population. Cells of the macrophage system originate in the bone marrow from the multipotential stem cell. This common committed progenitor cell can differentiate into the granulocyte or monocyte-macrophage pathway, depending on the microenvironment and chemical regulators. Maturation and differentiation of these cells may occur in various directions. Circulating monocytes may continue to be multipotential and give rise to different types of macrophages.

Macrophages exist as fixed or wandering cells. Specialized macrophages such as the pulmonary alveolar macrophages are the so-called dust phagocytes of the lung that function as the first line of defense against inhaled foreign particles and bacteria. Fixed macrophages line the endothelium of capillaries and the sinuses of organs such as the bone marrow, spleen, and lymph nodes. Macrophages, along with the network of reticular cells of the spleen, thymus, and other lymphoid tissues, are organized into the mononuclear phagocyte system (Fig. 3-5).

Host Defense Functions

Phagocytosis

The principal functions of mononuclear phagocytes in body defenses result from the changes that take place in these functions when the macrophage is activated (Box 3-1). Macrophages carry out the fundamental function of ingesting and killing invading microorganisms such as intracellular parasites, M. tuberculosis, and some fungi. In addition, macrophages remove and eliminate such extracellular pathogens as pneumococci from the blood circulation. The macrophage also has the capacity to phagocytize particulate and aggregated soluble materials. This process is enhanced by the presence of receptors on the surface of the Fc portion of IgG and C3. The ability to internalize soluble substances supports the increased microbicidal and tumoricidal ability of activated macrophages. Activation of macrophages or monocytes can result in the release of parasiticidal mediators and in receptor-mediate phagocytosis during malaria infection. The most likely location for this innate immune response is within the spleen which is crucial for development of immunity to malaria.

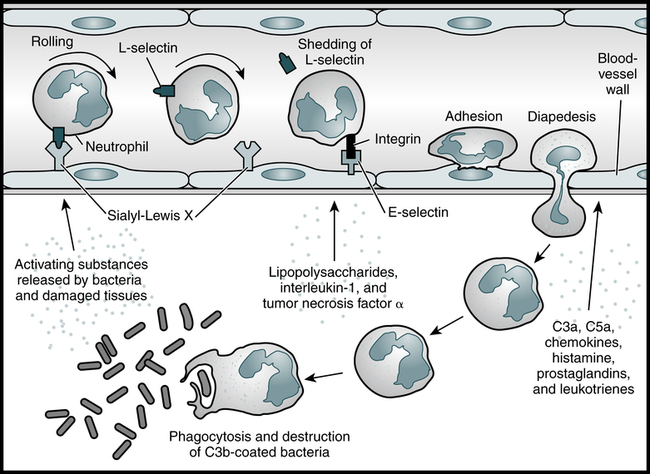

Acute Inflammation

Tissue damage results in inflammation, a series of biochemical and cellular changes that facilitate the phagocytosis of invading microorganisms or damaged cells (Fig. 3-6). If inflammation is sufficiently extensive, it is accompanied by an increase in the plasma concentration of acute-phase reactants (see Chapter 5). Leukocyte recruitment into inflamed tissue follows a well-defined cascade of events beginning with the capture of free-flowing WBCs to the vessel wall and subsequent leukocyte rolling along and adhesion to the inflamed endothelial layer. During rolling, WBCs come into close contact with the endothelial surface, which allows endothelium-bound chemokines to interact with their specific receptors on the leukocyte surface. This triggers the activation of integrins, which leads to firm leukocyte arrest on the endothelium. In addition, integrin-dependent signaling events induce cytoskeletal rearrangements and cell polarization, modifications necessary to help prepare the attached leukocyte to spread and crawl in search for a way out of the vasculature into tissue.

Neutrophils are among the first cells to arrive at the scene of an infection and are important contributors to the acute inflammatory response. As the neutrophil rolls along the blood vessel wall, the L-selectin on its surface binds to carbohydrate structures such as sialyl-Lewis X on the adhesion molecules on the vascular endothelium, and its progress is eventually halted. As the neutrophil becomes activated, it replaces L-selectin with other cell surface adhesion molecules, such as integrins. These molecules bind E-selectin, which is present on the blood vessel wall as a result of the influence of inflammatory mediators such as bacterial lipopolysaccharides and the cytokines IL-1 and TNF-α. The activated neutrophil then enters the tissues, where it is attracted to the infection site by a number of chemoattractants. The neutrophil can then phagocytose and destroy the C3b-coated bacteria. (Adapted from Delves PJ, Roitt IM: The immune system. First of two parts, N Engl J Med 343:37–49, 2000.)

1. Dilation of capillaries to increase blood flow

2. Microvascular structural changes and escape of plasma proteins from the bloodstream

3. Leukocyte transmigration through endothelium and accumulation at the site of injury

Once inflammation is triggered, it must be appropriately resolved or pathologic tissue damage will occur. In some diseases, the body’s defense system (immune system) inappropriately triggers an inflammatory response when no foreign substances are present. In these autoimmune disorders, the body’s normally protective immune system causes damage to its own tissues (see Chapter 28).

SEPSIS

Sepsis begins when the innate immune system responds aggressively to the presence of bacteria. Toll-like receptors (TLR) cause the antigen presenting cell (APC) to produce proinflammatory cytokines. Biochemical markers associated with sepsis include tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukins (ILs) IL-1 and IL-6, a proinflammatory cytokine. Other proteins produced in response infection and/or inflammation include procalcitonin and chemokine production. Another consequence of inflammation is that the liver is stimulated to produce C-reactive protein (C-RP) (see Chapter 5).

Disorders of Neutrophils

Noninfectious Neutrophil-Mediated Inflammatory Disease

Although neutrophils provide the major means of defense against bacterial and fungal infections, they can also be destructive to host tissues. The same oxidative and nonoxidative processes that destroy microorganisms can affect adjacent host tissues. A number of disease states correspond to inappropriate phagocytosis (Box 3-2), as with prolonged activation of NADPH oxidase. This process occurs when phagocytes attempt to engulf particles that are too large. The phagocyte releases oxygen radicals and granule contents onto the particle, but these escape into the surrounding tissues, generating tissue damage. This is often observed in response to dust inhalation and smoking (e.g., nicotine) and in persistent infections such as cystic fibrosis. In addition, many autoimmune diseases are thought to be caused by inappropriate activation of the process of phagocytosis, whereby the body attacks its own cells and tissues. Examples include rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and Graves’ disease.

Congenital Neutrophil Abnormalities

A small number of patients have congenital abnormalities of neutrophil structure and function (Box 3-3).

Chronic Granulomatous Disease

The chronic granulomatous diseases (CGDs) are a genetically heterogeneous group of disorders of oxidative metabolism affecting the cascade of events required for H2O2 production by phagocytes. Patients with X-linked CGD (X-CGD) have a mutation in CYBB encoding the transmembrane gp91phox subunit of phagocyte NADPH oxidase required for microbicidal ROS production by neutrophils and monocytes. As a result, patients have life-threatening infections and granulomatous complications. If a suitable hematopoietic stem cell donor is available, it can cure X-CGD, but graft-versus-host disease (see Chapter 31) is a significant risk.

Monocyte-Macrophage Disorders

Monocytes-macrophages have been shown to be abnormal in a variety of diseases (Table 3-2). The abnormality is partial and no related association with increased susceptibility to infection has been established. In cases of severely depressed migration of monocytes, however, it is likely that this dysfunction predisposes a patient to infection because other defects of host defense coexist in these disorders.

Table 3-2

Primary and Secondary Abnormalities of Monocyte-Macrophage Function

| Abnormality | Condition/Group |

| Defect in phagocyte killing | Chronic granulomatous disease, corticosteroid therapy, newborn infants, viral infections |

| Defective monocyte cytotoxicity | Cancer, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome |

| Defective release of macrophage-activating factors | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), intracellular infections (e.g., lepromatous leprosy, tuberculosis, visceral leishmaniasis) |

| Depressed migration | AIDS, burns, diabetes, immunosuppressive therapy, newborn infants |

| Impaired phagocytosis | Congenital deficiency of CD11 to CD18, monocytic leukemia, systemic lupus erythematosus |

Screening Test for Phagocytic Engulfment

Screening Test for Phagocytic Engulfment

Principle

A mixture of bacteria and phagocytes is incubated and examined for the presence of engulfed bacteria. This simple procedure may be useful in supporting the diagnosis of impaired neutrophilic function in conjunction with clinical signs and symptoms (Fig. 3-7).

See ![]() website for information related to performing the procedure.

website for information related to performing the procedure.

Chapter Highlights

• The entire leukocytic cell system is designed to defend the body against disease. Each cell type has a unique function and behaves independently and, in many cases, in cooperation with other cell types.

• The primary phagocytic cells are the neutrophilic leukocytes and the mononuclear monocytes-macrophages.

• The neutrophilic leukocyte provides an effective host defense against bacterial and fungal infections. Although the monocytes-macrophages and other granulocytes are also phagocytic cells, the neutrophil is the principal leukocyte associated with phagocytosis and a localized inflammatory response.

• Phagocytosis can be divided into movement of cells, engulfment, and digestion.

• Cells communicate with each other and their environment through soluble mediators and during direct contact (e.g., phagocytosis). These interactions occur through cell surface receptors that mediate cell-cell binding (adhesion) of leukocytes.

• Three protein families (immunoglobulin, integrin, selectin) are associated in a network of cellular interactions in the immune system.

• Qualitative monocyte-macrophage disorders manifest as lipid storage diseases, including a number of rare autosomal recessive disorders.

• Leukocyte adhesion deficiency ultimately leads to recurrent and often fatal bacterial and fungal infections.