Chapter 46 Caving and Cave Rescue

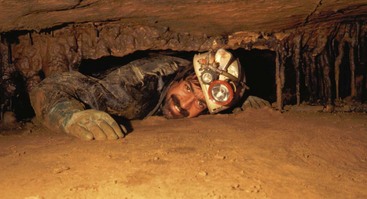

Caves can contain hostile environments. They present physical challenges such as water obstacles, extreme temperatures, confined spaces, exposure to heights, and hazardous surfaces varying from slippery mud to jagged calcite that can catch or snag on cavers’ clothing. Atmospheres can contain dangerous levels of carbon dioxide, methane, or hydrogen sulfide. Unusual pathogens, such as Histoplasma capsulatum, Leptospira species and rabies virus, are more likely to be found in caves. Well before engaging in underground duties, medical and rescue professionals should become thoroughly familiar with the harsh realities of the cave environment and anticipate unusual diagnoses in patients who frequent caves (Figure 46-1). Underground risks, both physical and medical, can be avoided or mitigated.

Environment

The continuous conduit leading through a cave is known as a passage. Passages can be huge, with room dimensions so large it is difficult to see distant walls (Figure 46-2) even with a light, whereas just around the next corner, the passage can change to tight impenetrable cracks or a dead end (Figure 46-3). Some cave passages wander around in a maze-like pattern that may total many miles in an area as small as a few acres of ground. Other caves may go for miles in the same direction and contain dozens of miles of passage. Many caves are only a few hundred feet long and have only low, tight, belly-crawl passage. A passage that opens into a wide area is called a room, whereas a tight, narrow passage may be further described as a squeeze or crawl.

Caves are formidable, dark, and often dangerous for the unprepared. Considering that running, seeping, or standing water originally formed most caves, it is not surprising that water is a major part of many cave environments. Cavers and rescuers must be prepared to negotiate anything from crawls in water-filled tubes (Figure 46-4) to underground rivers so large that a boat is required.

A common scenario in cave rescue is the concern for hypothermia. Most caves are cool to cold, but temperature differentials can exist within a single cave, depending on exposure, orientation, and water flow. Temperature differentials or pressure differences can result in winds flowing through cave passages. It is not uncommon for a caver to be supine or prone in 4 inches (1.6 cm) of 13° C (55° F) water with his or her back pressed against cold rock, facing a stiff breeze (Figure 46-5).

Personal Safety

A mountaineering type of helmet, with a nonelastic “three-point” chin strap that keeps it planted properly on the head, is a must. The helmet protects against impact with the hard and often sharp rock of cave ceilings and walls in tight or low passages and offers protection against falling rock. The helmet is also a convenient mounting platform for the required light source (Figure 46-6).

Cave Search

When the location of the rescue subject is unknown, a search will be required. Searching a cave is a potentially hazardous task and must be done meticulously and under good planning and management.13 A manager of a cave search uses the same basic skills as does an above-ground rescuer. Once the decision is made to begin an in-cave search, teams of cavers will be formed into task forces. Each search task force’s role is to look for, preserve, record, and recover clues that will lead to finding a missing person. The task force should consist of two or three members, one or more of whom should be familiar with basic search techniques, the cave being searched, and cave map reading. Members should be able to perform basic first aid, including patient assessment. In addition to personal caving gear discussed earlier, required equipment includes basic medical supplies, materials to mark passages, pencil and paper, food and liquid for the search subject, hypothermia protection, a map, and a compass. A marking system using colored flagging tape or other means should be established to mark side passages that have already been searched and to differentiate the best route in and out once a subject has been located.

Basic Evacuation

Not all cave rescue scenarios benefit from the fitness and ability of a caver such as Samuel or the presence of a skilled paramedic who can resolve a medical situation. If litter transport is deemed necessary, the next difficult decision is which litter (or litters) to use. On any given evacuation, this selection involves a fine balance of requirements. Maneuvering a bulky litter through narrow cave passages can be a challenging proposition. In larger caves, or where a vertical raise is required, basket litters are the best choice. Plastic-bottomed versions are preferable over steel and mesh versions because plastic allows the option of dragging the litter where necessary (Figure 46-7). In tighter caves, drag-sheet types of litters, such as the wraparound SKED, provide low profile and relative flexibility, but they are less comfortable or protective for the patient.

FIGURE 46-7 Plastic litter offers patient protection and slides easily through passage.

(Courtesy Kris H. Green.)

A reasonable first-aid kit for a cave rescue operation should contain writing materials for recording patient condition, basic medications, airway management tools, bandages, cervical collars, and splints. Sealing each item in plastic helps keep out cave grit, and the entire kit can be packaged in a large-mouthed bottle or other watertight, durable container. The kit should be able to fit into the caver’s own cave pack because it is much easier to carry one large pack than two smaller ones. The kit should target common injuries. More specialized supplies can be brought in as needed, but a comprehensive kit is not compatible with reasonable movement through the cave. See Box 46-1 for a minimal list of items to include in a cave rescue medic kit.

Logistics

The Incident Command System (see Chapter 36), or a modified version of it, provides the best framework for managing cave rescue personnel by performing required functions while maintaining a reasonable span of control. Generally, the functions required during a cave rescue are similar to those required during any other rescue, although the specific means of accomplishing those functions will vary.

Environmental Hazards

Other environmental hazards posed by caves may be more readily recognized and should also be considered before any rescue. As discussed earlier, water and caves are usually closely associated. Created by water, caves are a natural deposit for overflow or drainage from a variety of sources. This makes caves particularly prone to flooding with little or no warning. A recreational caver (Figure 46-8) or rescuer caught in a flooding cave is in mortal danger.

Medical Hazards

The most common cave-acquired disease is histoplasmosis, which is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus present worldwide but especially prevalent in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys of the United States.1 It is associated with bird, and especially bat, guano (Figure 46-9).12 At a national caving convention in 1994, at least 18 people contracted symptomatic histoplasmosis, with an attack rate of greater than 70% for attendees going into two local caves.1 A follow-up skin test survey found that 60% of one group of cavers showed evidence of Histoplasma capsulatum exposure.1

Cavers get histoplasmosis by breathing dust from affected parts of the cave. Incubation is 2 to 3 weeks. Most primary cases are not even recognized, because they resemble a flulike illness with fevers, headaches, and cough.21 Persons with significant illness demonstrate patchy lung infiltrates, which may calcify, and hilar lymphadenopathy. Some cases progress to cavitation or dissemination. Detection of urinary antigen is the mainstay of diagnosis. In most cases treatment is not necessary. If symptoms last longer than a month, treatment is indicated with itraconazole or other azole drugs or, in cases of dissemination, amphotericin B. Patients may require 3 to 6 months of treatment.9

Leptospirosis has been reported on caving expeditions to tropical climes but is probably a risk in temperate regions as well.5,6,17,22 Transmission occurs when water contaminated by urine from infected animals comes into contact with mucous membranes, the conjunctivae, or abraded skin.18 Cavers often crawl through small passages in the rock to explore what lies beyond, sometimes greatly abrading the skin, especially in hot humid caves where protective clothing may be minimal. Immersion may increase the risk.4 Water that has percolated through carbonate rocks in which most caves form will have a higher pH, which favors survival of leptospires.11

Leptospirosis manifests with fevers, chills, myalgias, and headache after a 1- to 4-week incubation.16 More specific findings are conjunctivitis, proteinuria, and hematuria. It is most commonly diagnosed with serum microscopic agglutination titers (MAT). The diagnosis is confirmed by a fourfold rise in MAT, but is suggested by a titer of 1 : 800 with appropriate exposure and symptoms. Treatment is IV penicillin or ceftriaxone for severe cases and oral doxycycline for mild cases. It can be prevented with 200 mg of weekly doxycycline.23

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend rabies vaccination for “spelunkers.” This dates from a concern about two cases of rabies in cavers that were attributed to aerosol transmission. These two people separately visited Frio Cave in Texas, where millions of bats congregate, and developed rabies soon thereafter. Subsequent research demonstrated the presence of rabies virus in the air of Frio Cave, presumably from bat respiratory secretions.2,24 Transmission to animals exposed only to airborne virus has since been demonstrated in the laboratory and in Frio Cave.7,8 Therefore in the context of massive bat maternity colonies, aerosol transmission of rabies appears possible.

Still, the matter is not so simple. In both cases, there was a more probable cause for rabies than aerosol transmission.10 In the first case, the caver was employed in a rabies laboratory and worked inoculating bats with rabies virus.14 The second patient denied being bitten by a bat, but was noted to have a bleeding lesion on the face while exiting Frio Cave.10,15

So what are cavers to do? Certainly, anyone doing bat research needs to be vaccinated against rabies and to check titers routinely. Anyone working in caves like Frio needs appropriate masks to filter the hazardous atmosphere, of which rabies is just one component. It is questionable whether the sport caver really has any business at all roaming in a bat maternity colony.3 Decades of exposure have not resulted in further documented cases of cavers contracting rabies. Although some persons have called for vaccination of all cave explorers, the opinion is not unanimous.3 Each caver needs to decide on the level of risk and act accordingly.

Patient Care

Data compiled for American Caving Accidents indicate that the leading cause of caving injury is falls, and that hypothermia, fractures, and head injuries top the list of complaints.19,20 Unfortunately, with significant falls, spinal injury must be contemplated, which compounds the transportation challenge. The approach to medical care should be similar to any other medical situation, with a notable difference: the patient has suffered an acute injury but will be confined for an extended period. Care, then, will be a combination of acute emergency responses adapted for a patient who is, for all practical purposes, bedridden.

Once the patient has been stabilized and packaged, the assessment process should continue throughout the evacuation. It is best if one medical person stays with and monitors the patient throughout the evacuation (Figure 46-10). The ideal medic is a strong caver with good single-rope technique skills and at least paramedic training. By constantly staying with the patient, the medic is best placed to observe changes. The medic will need to know the complete patient history and clinical evolution while en route in order to make decisions that affect the extrication effort, such as needs for urgency and patient orientation. Although other evacuation personnel may cycle through the rescue, the constant presence of the medic is reassuring to the patient. Because the medic may need to spend many hours with the patient, he or she should not take part in the strenuous activity of litter handling.

Closing Comments

People interested in enhancing cave rescue training should contact the National Cave Rescue Commission (NCRC). The NCRC conducts week-long cave rescue seminars and weekend orientations across the United States. It can be reached at the address above as the National Cave Rescue Commission of the National Speleological Society or online at http://www.caves.org/io/ncrc/.

1 Ashford DA, Hajjeh RA, Kelley MF, et al. Outbreak of histoplasmosis among cavers attending the National Speleological Society Annual Convention, Texas, 1994. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:899.

2 Brass DA. Airborne transmission of rabies virus. In: Rabies in bats: Natural history and public health implications. Ridgefield, Conn: Livia Press; 1994:169-175.

3 Brass DA. Concerns in cave exploration. In: Rabies in bats: Natural history and public health implications. Ridgefield, Conn: Livia Press; 1994:311-322.

4 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of leptospirosis among white-water rafters: Costa Rica, 1996. MMWR. 1997;46:577.

5 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of acute febrile illness among participants in Eco-Challenge Sabah 2000. MMWR. 2000;49:816.

6 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: Outbreak of acute febrile illness among athletes participating in Eco-Challenge-Sabah 2000: Borneo, Malaysia, 2000. MMWR. 2001;50:21.

7 Constantine DG. Rabies transmission by nonbite route. Public Health Rep. 1962;77:287.

8 Davis AD, Rudd RJ, Bowen RA. Effects of aerosolized rabies virus exposure on bats and mice. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1144.

9 Deepe GS. Histoplasma capsulatum. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005:3012-3026.

10 Gibbons RV. Cryptogenic rabies, bats, and the question of aerosol transmission. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:528.

11 Gordon SC, Turner L. The effect of pH on the survival of leptospires in water. Bull World Health Organ. 1961;24:35.

12 Hoff GL, Bigler WJ. The role of bats in the propagation and spread of histoplasmosis: A review. J Wildl Dis. 1981;17:191.

13 Hudson S. Manual of U.S. cave rescue techniques, ed 2. Huntsville, Ala: National Speleological Society; 1988.

14 Irons JV, Eads RB, Grimes JE, et al. The public health importance of bats. Tex Rep Biol Med. 1957;15:292.

15 Kent JR, Finegold SM. Human rabies transmitted by the bite of a bat: With comments on the duck-embryo vaccine. N Engl J Med. 1960;263:1058.

16 Levett PN. Leptospirosis. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. ed 6. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005:2789-2798.

17 Mortimer RB. Leptospirosis in a caver returned from Sarawak, Malaysia. Wilderness Environ Med. 2005;16:129.

18 Phraisuwan P, Spotts Whitney EA, Tharmaphornpilas P, et al. Leptospirosis: Skin wounds and control strategies, Thailand, 1999. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:1455.

19 Putnam WO. An overview of the 2002 and 2003 incidents. NSS News. 2005;63:2.

20 Putnam WO. An overview of the 2004 and 2005 incidents. NSS News. 2007;65:2.

21 Sacks JJ, Ajello L, Crockett LK. An outbreak and review of cave-associated Histoplasmosis capsulati. J Med Vet Mycol. 1986;24:313.

22 Self C, Iskrzynska W, Waitkins S, et al. Leptospirosis among British cavers. Cave Science. 1987;14:131.

23 Takafuji ET, Kirkpatrick JW, Miller RN, et al. An efficacy trial of doxycycline chemoprophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:497.

24 Winkler WG. Airborne rabies virus isolation. J Wildl Dis. 1968;4:37.