2 Causes and course of the illness

CAUSES

2.1 How common is bipolar disorder?

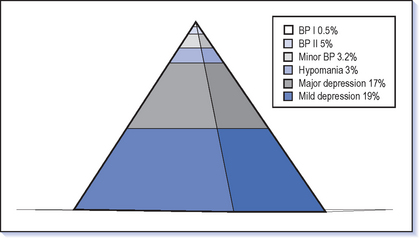

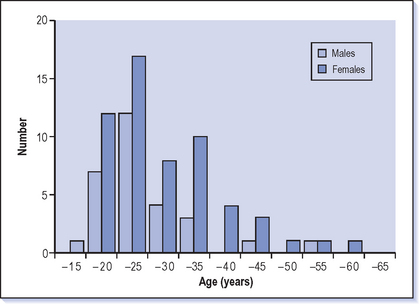

The simplest answer to this is that it occurs in 1% of people. This seems to be true around the world in any population investigated. However, there is a spectrum from severe mania through milder forms of manic depression to recurrent depression and on to normal mood variation. It is always difficult when you have a spectrum to know exactly where to draw the lines within this to define the different disorders. Tight definitions of manic depression would give a figure of less than 1%; broader definitions which include hypomania would give figures from 2 up to 10% (Fig. 2.1).

2.2 What causes manic depression?

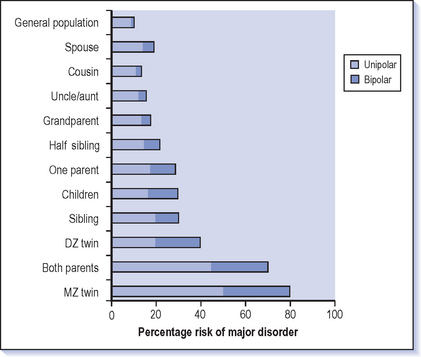

‘Nature or nurture, genes or environment?’ is a common question in the cause of any illness that is rarely answered definitively. For bipolar illness (particularly the more severe end of the spectrum–mania rather than hypomania) the genes/nature answer seems more likely. Bipolar illness tends to run in families and the more closely an individual is related by blood to a manic depressive the more likely that person is to develop the illness. If one parent suffers from manic depression and a child is adopted away and brought up by another family, there is still the same risk of developing manic depression as if the child was brought up by the biological parents. In the case of twins, if one twin suffers from manic depression then the chance of the other twin becoming ill is higher in cases of identical rather than fraternal twins (Smoller & Finn 2003). All of these observations indicate that bipolar illness is strongly influenced by genetic factors. However, it is not the whole story as even identical twins are not 100% concordant: if one identical twin suffers from manic depression the other will have a bipolar illness in about 50% of cases and recurrent depression in about 30%. However, there are still 20% of identical twins who are discordant, i.e. one is illness-free.

2.3 What family history am I likely to elicit from a patient with manic depression?

![]() About 70% of bipolar patients will have a close relative (a parent or sibling) who suffers either from manic depression or from serious (usually recurrent) depression. Only 20% will actually have a bipolar relative (Case vignette 2.1). The equivalent figures for the general population are about 10% (depression) and 1% (bipolar). First-degree relatives (sibling, parent or child) of someone who is manic depressive have about a 10-15% chance of having or developing manic depression (Gershon et al 1982, Gottesman 1991, Smoller & Finn 2003) (Fig. 2.2).

About 70% of bipolar patients will have a close relative (a parent or sibling) who suffers either from manic depression or from serious (usually recurrent) depression. Only 20% will actually have a bipolar relative (Case vignette 2.1). The equivalent figures for the general population are about 10% (depression) and 1% (bipolar). First-degree relatives (sibling, parent or child) of someone who is manic depressive have about a 10-15% chance of having or developing manic depression (Gershon et al 1982, Gottesman 1991, Smoller & Finn 2003) (Fig. 2.2).

2.4 How many genes are involved?

The questions that are likely to emerge include: ‘What are the normal functions of these genes?’ and ‘To what extent do we need to be liable to depression and elation?’

2.6 Which genes cause the illness?

We would all include those with a bipolar I disorder, but would we also include bipolar II patients?

We would all include those with a bipolar I disorder, but would we also include bipolar II patients?The question of where we draw the lines around the phenotype is still one of the basic questions that need to be answered (see Ch. 1).

2.7 Who is likely to develop manic depression?

![]() There are two ways of finding people who are likely to develop a bipolar illness. The first is looking in the families of those who already suffer from manic depression, as the risks are elevated in close family members (see Q 2.3). The second way is to look amongst those who are suffering from depression but have not had episodes of mania. About 15% of those who suffer from recurrent depression will develop mania.

There are two ways of finding people who are likely to develop a bipolar illness. The first is looking in the families of those who already suffer from manic depression, as the risks are elevated in close family members (see Q 2.3). The second way is to look amongst those who are suffering from depression but have not had episodes of mania. About 15% of those who suffer from recurrent depression will develop mania.

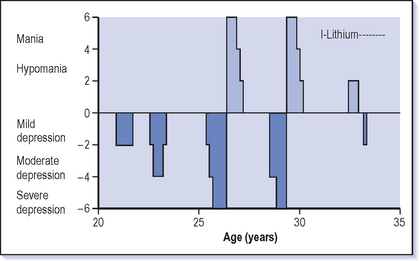

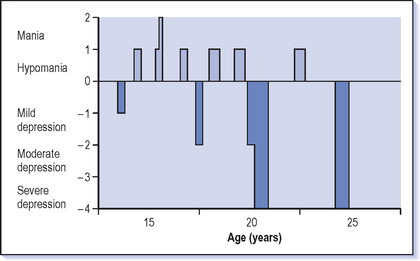

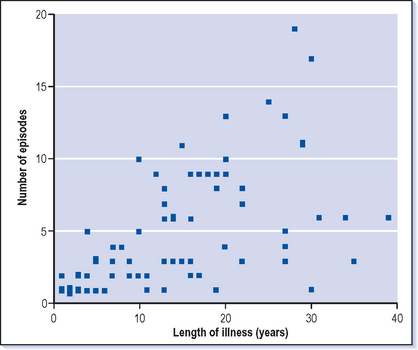

It is not possible to predict who will develop manic depression and it is a continual surprise when those people who have been treated for depression for several years suddenly become manic (see Case vignette 4.1). However, those whose illness started at a young age (particularly in the teenage years or the twenties) and those who have frequent episodes and rapid shifts between depression and euthymia are particularly at risk (Fig. 2.3).

2.8 Does adversity bring on manic depression or cause relapses?

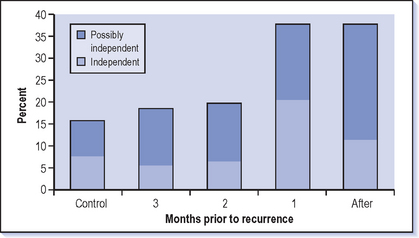

There have been several studies (e.g. Hunt et al 1992) that have tried to tease out these various factors which have led to the conclusion that adverse events do play a part. The first episode of manic depression is likely to be at a time of other difficulties in the person’s life, and recurrences are also likely to coincide with adverse life events (Fig. 2.4). However, the contribution from life events is small and it is best to look at them as triggers rather than causes.

2.9 Does upbringing affect the chance of developing manic depression?

Those who have had a difficult and abusive childhood are more likely to suffer from depression and personality problems. An unhappy childhood does not make anyone more liable to develop manic depression and the childhoods of manic depressives are usually normal. Those who suffer from schizophrenia are more likely to have had adverse physical problems in childhood, difficult births with obstetric complications and illnesses such as meningitis, encephalitis and head injury. However, this does not seem to be true for manic depressives–or at least not to the same extent. It is unlikely that adverse childhood experiences offer an explanation for the development of manic depression.

2.11 Does the use of illicit drugs cause manic depression?

Stimulant drugs can also precipitate mania among manic depressives. Illicit drugs seriously worsen the course of the illness and its treatment, and invariably the frequency of recurrence, complications and compliance are affected. Whether taking stimulants can actually set off a lifelong propensity to mania and depression is much less certain. If this were beyond doubt, the incidence of manic depression would have increased considerably in recent years and that probably is not the case.

2.12 Do any medicines cause mania or depression?

The drugs most often associated with mania are the corticosteroids which ties in with the link with Cushing’s disease (see Q 2.10). Minor elevations of mood with euphoria are felt by many people taking steroids but it is rare that this extends to the full manic syndrome. However, depression is a more common and debilitating outcome of this treatment.

Those with Parkinson’s disease who are having treatment with L-dopa can also experience elevation of mood and other manic symptoms. The use of stimulants including methylphenidate can cause mania (see Q 2.11) and this can cause significant problems when considering the diagnosis in adolescents who already have deficits in attention. However, the most common drugs to induce mania are antidepressants (see Q 3.15).

There is a long list of drugs that are associated with depression apart from steroids (Box 2.1). The induction of depression by the antihypertensive reserpine–which depletes monoamines including noradrenaline (norepinephrine) and serotonin–was the original basis for the theory that monoamines were the important neurotransmitters in depression.

2.13 Is bipolar illness more common among some ethnic groups?

Several studies show that minority ethnic groups are more likely to develop manic depression. This may be because migrants are particularly vulnerable to this illness, with an increased rate among those who have moved between countries. The explanation for this could be that those who do move have a particular type of personality (energetic, highly motivated, ‘hyperthymic’) or that the stress of migrating and adapting to a new culture is causal.

2.15 Is manic depression becoming more common?

The answer is probably not but we are getting better at recognising the range of manic depressive illnesses (although some would say we have got worse at drawing limits around a serious illness). The closer that epidemiological studies come to looking at the community, rather than judging the prevalence of manic depression from hospital samples, the larger the number of cases that are found. More patients who had previously been treated as suffering from recurrent depression are now recognised as bipolar because, when examined over a long period of time, it is clear they have periods of elevated mood between their episodes of depression.

COURSE

2.16 At what age does manic depression start?

![]() The first episode can occur at any age after puberty. (Whether episodes of mania occur before puberty is controversial; if it does happen, it is very rare.) The average age is about 30 years but this covers a very broad range (see Fig. 2.5). Most patients will have had their first major episode of affective illness in their twenties.

The first episode can occur at any age after puberty. (Whether episodes of mania occur before puberty is controversial; if it does happen, it is very rare.) The average age is about 30 years but this covers a very broad range (see Fig. 2.5). Most patients will have had their first major episode of affective illness in their twenties.

Sometimes patients will recall earlier but more minor episodes going back to their teens. Later onsets are, however, not uncommon, particularly in people who have already experienced depressions. In the elderly mania is much more likely to be preceded in earlier life by periods of depression, so it may not be apparent that this is a bipolar illness until old age. A first episode of mania can certainly occur in the elderly but if there have been no previous periods of depression then physical illness should be excluded as a trigger factor (see Q 2.10).

What is striking is that there is usually a gap of 5-10 years between the onset of symptoms and the diagnosis being made (see Q 1.16). This is partly because it is impossible to make a bipolar diagnosis when only depression has occurred so far and also because the symptoms of both mania and depression may initially be mild and difficult to recognise. It is also hard to disentangle bipolar symptoms from personality and situational factors in the early years. It can be difficult to make this diagnosis, but it should be borne in mind in everyone who presents with depression. However, this needs to be balanced with falling into the other trap of making the diagnosis when it is not appropriate.

The earlier the diagnosis can be made, the earlier effective treatment can be provided, thus reducing the impact on the patient’s life and improving the long-term outcome.

2.17 Does an early onset mean a more severe condition?

The treatment of adolescents with bipolar illness can be very challenging, not intrinsically because of the nature of the illness but because of the nature of the teenager. Teenagers are more likely to have complications such as drug misuse and poor compliance with treatment (see Q 6.20)

2.18 How common is recurrence after a single episode of mania?

2.22 How often does mania switch into depression?

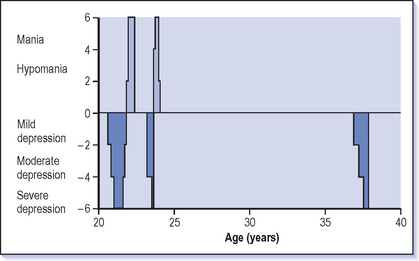

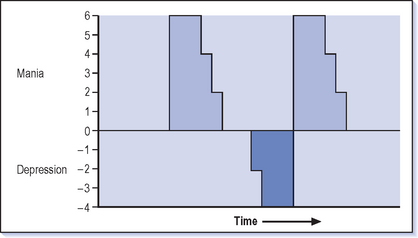

Some patients have a regular pattern of switching in their illness so that, for example, they can expect to experience depression after mania (Fig. 2.7). Men are particularly likely to have this pattern of illness.

2.23 How quickly do episodes of mania and depression come on?

‘I can go from zero to supernova in 48 hours’ is the classic comment about the onset of mania but sometimes the onset is over several weeks and it is only as behaviour becomes more extreme that boorish irritable behaviour can be clearly seen to be part of a manic swing. Depression is more commonly insidious in its onset over a few weeks rather than a few days and tends to move from mild to more severe states gradually.

2.25 How can the future course of the illness be predicted?

Past performance is the best predictor of future prospects. It can be very useful to draw up a life chart with a patient (see Fig. 6.1) which shows when their illness started, what episodes they have had and what treatment has been taken. Looking at the frequency, severity and type of previous episodes in relation to what medications have been used can indicate a pattern and give some indication of the future. However, if you look very hard it is easy to see patterns that are not really there.

When trying to help someone to predict the future course, look particularly at the well interval for some guidance as to when the next episode is likely to occur. For instance, if someone suffered a period of mania as a student in their twenties and then a period of depression in their forties (Case vignette 2.2) it is reasonable to be confident that there will be a further lengthy well interval (see Q 2.18). However, strong predictions in manic depression should be avoided as the illness often surprises, both with patients with frequent relapses reaching lengthy stability and others who have been free of the illness for many years experiencing multiple episodes.

2.26 Does bipolar II illness develop into bipolar I?

Generally the pattern of bipolar illness for any particular person tends to be fairly constant, both in its severity in each episode and the frequency of episodes. So you would expect that if only hypomanic episodes have occurred that this will be the pattern for the future. However, just as there is a small number of people each year that ‘convert’ from recurrent unipolar depression to bipolar illness there is also a small number that convert from bipolar II (recurrent depression and hypomania, Fig. 2.8) to bipolar I (recurrent depression and mania). This is particularly likely to occur if they are taking high doses of antidepressants (especially if they are not taking lithium) or if the depressions themselves are becoming more severe and so require higher levels of treatment. Stopping treatment such as lithium suddenly can precipitate mania for the first time and that is why it is important to change from treatments only slowly (see Q 5.27).

2.27 How common is chronic illness?

About a quarter of those with manic depression will be experiencing symptoms which are so persistent that they are rarely free of them. Most commonly these are chronic depressive symptoms which are at a relatively mild but still distressing and disabling level. There are other patients who become chronically manic although this is rarer. A similarly small proportion continues a relentless course of switching between mania and depression over days/weeks or months in the longer term (see Q 1.12). Although there are not many of these patients about, if you look at any long-term facility for chronically ill psychiatric patients there will be a number of people with manic depression among the larger group with chronic schizophrenia. These patients are commonly women who have started their illness at a rather later age and who also have prominent cognitive impairment.

2.28 Is bipolar disorder a progressive condition?

There is a small increase in the frequency of relapse with time, but this effect is small. It would be expected that each of the first few episodes has a shorter well interval but then usually a more stable pattern emerges (Fig. 2.9). However the course of manic depression is endlessly variable!

Those people who have the most severe illnesses will usually suffer frequent relapses and poor recovery right from the start. It is usually apparent from early on who has a better prognosis as they will experience shorter, less severe episodes with a long well interval. However the social toll of the illness can grow with time even if the frequency and severity of the episodes do not. Losing close relationships (including divorce, which is particularly likely for manic depressives) and a lack of consistency at work often lead to cumulative personal damage.

2.29 Is manic depression a permanent condition?

There is a small group of between 10 and 20% of people who have suffered several episodes of illness who then have a prolonged period of many years free of bipolar disorder (see Fig. 2.6). However it is not uncommon to see people who have been well for many years (see Case vignette 2.2) who experience a recurrence 20 years after their last episode. It would appear that the vulnerability to manic depression never goes completely away even when people have been well for many years.

2.30 What is the long term outcome for bipolar disorders?

Professor Angst of Zurich has contributed an enormous amount of information about bipolar disorders and their long term course and outcome. His studies have indicated that at 20 years after the start of their illness, more than two-thirds of manic depressives will still be experiencing disabling problems from their illness (Table 2.1) (Angst & Sellaro 2000).

| Outcome | Description | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Recovered | Good function, no episode in 5 years | 16 |

| Remitted | Good function but more than one episode in 5 years | 25 |

| Incomplete remission | Impaired function, still recurrent | 35 |

| Chronic | More than 2 years in episode | 16 |

| Suicide | 8 |

Adapted from Angst & Sellaro (2000).

2.31 Does bipolar illness develop into dementia/schizophrenia?

There is no evidence that manic depression leads on to dementia. It is true that sometimes the early stages of dementia present with prominent mood symptoms–usually depression but sometimes also of elation. Agitation and restlessness are themselves common symptoms in dementia and can be the presenting complaints early in the illness. There is some evidence of cognitive impairment in manic depression. If this does progress it is a very slow progression and certainly not the rapid progression usually seen in dementia (see Q 6.3).

There is a small number of patients who are clearly diagnosed as having manic depressive illness who then develop symptoms that are typical of schizophrenia. After a few years it then becomes clear that they are suffering from chronic schizophrenia rather than manic depression. Some people say the diagnosis was wrong to start with and that the manic illness was an early stage of schizophrenia, and if you had searched more carefully you would have found features of schizophrenia. It is very common for those with schizophrenia to suffer prominent symptoms of depression and up to a third experience excited and elated periods but the symptoms typical of schizophrenia continue throughout.

The border between manic depression and schizophrenia is a blurred one, and you will find some psychiatrists who seem to diagnose almost everybody with a psychotic illness as having a schizoaffective disorder as they can find elements of schizophrenia and also of affective illness in every severe mental illness. This doesn’t seem to be a very helpful way of proceeding as most trials of treatment are based on one diagnosis or the other and treatment trials in schizoaffective disorder are few and far between. The point of diagnosis is to guide treatment and estimate prognosis and that is why it is worth making the split between the diagnoses. Having said that, there are patients who clearly do stand on the border and merit the diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder (see Q 1.15).

2.32 What is likely to trigger off a recurrence?

When you look carefully at stressful life events there is an excess before both depression and mania (see Fig. 2.4). However, adverse life events are probably only responsible for about 20% of episodes of mania or depression. There is some evidence that early episodes of an illness are more likely to be triggered by adverse events. It is difficult to tease out the effects of life events from the natural course of the illness. Unpleasant and distressing events happen to all of us (on average three serious events a year) and if you become ill (in any way but particularly psychiatric illness) you will tend to try to find a link to something that has happened recently, in a search for meaning.

![]() Other well-known precipitants include stopping treatment, in particular suddenly stopping lithium (see Q 5.27). Having a baby is a potent precipitant, particularly of mania but also of depression (see Q 6.17). Some people also report a seasonal element to relapses of their manic depression (see Q 2.34).

Other well-known precipitants include stopping treatment, in particular suddenly stopping lithium (see Q 5.27). Having a baby is a potent precipitant, particularly of mania but also of depression (see Q 6.17). Some people also report a seasonal element to relapses of their manic depression (see Q 2.34).

2.33 Does the menstrual cycle affect bipolar illness?

In mania there are no known effects of the menstrual cycle.

The potency of childbirth to precipitate both mania and depression is well known (see Q 6.17) and this is a common time for the illness to appear. It has been reported that manic depression can arise for the first time at the menopause, but this is rare. There is no clear connection between the illness and the menopause which would allow you to predict for a woman what is likely to occur to her manic depression at this time. Some find that their illness actually improves and they achieve more stability; others report it to be a stormy time for their illness. It can be tempting to try using hormone replacement therapy to alleviate affective symptoms but it is better to focus on the usual treatments at least initially and only experiment with hormonal treatment if this is not successful.

2.34 Does manic depression occur more often at a particular time of year?

Bright artificial light is an effective treatment for recurrent winter depression (see Q 3.34). This approach does require a considerable time commitment: at least an hour in the morning sitting very close to and looking repeatedly at a light. Some people are able to stick with this but most find it difficult to sustain. There are now some ‘light hats’–baseball-type caps with lights in the visor–which are easier to use, but look slightly ridiculous and patients should probably be discouraged from going out in them unless they are trying to gain a reputation for eccentricity. Alternatives to the light treatment are walking outside or antidepressant drugs.

2.35 How important is a regular sleep pattern?

Most of those who are depressed will be having difficulty sleeping at night but will often resort to sleeping in the day. This can lead to the sleep pattern becoming very erratic. It is worth encouraging the depressed to try to get as much of their sleep as possible at night and not sleep in the day (see Q. 3.30).

A proportion of bipolars who are depressed are sleeping excessively and this pattern also exacerbates depression. Again it is very difficult to change this but encouraging them to get up at a reasonable time and not going to bed too early is worthwhile. A more extreme approach of sleep deprivation can be an effective antidepressant treatment both in unipolar and bipolar depression. This involves keeping patients awake all night, usually for 3 or 4 nights (and days). It can lead to a beneficial change in mood but is usually only a short-term solution. Sometimes it is helpful for those with an intractable depression when a shift out of their depression even for a short period can give you and them hope that a change can be made.