Case 7

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The patient was referred to the electromyography (EMG) laboratory.

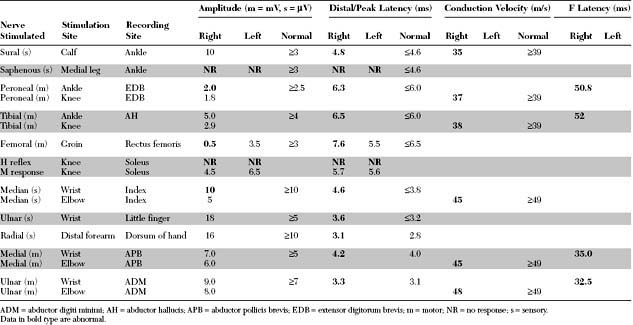

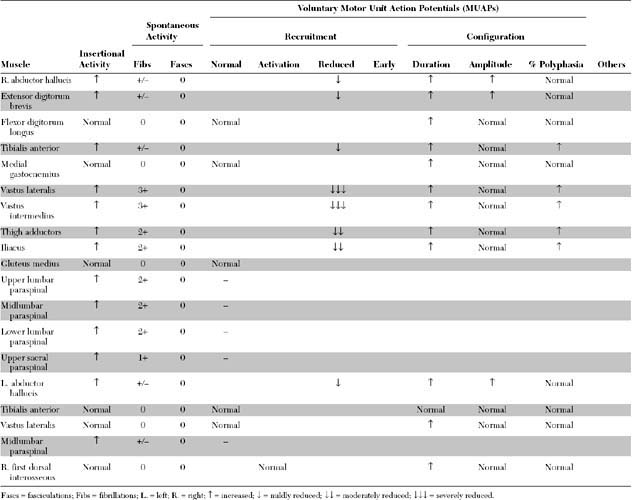

Please now review the Nerve Conduction Studies and Needle EMG tables.

QUESTIONS

EDX FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATION OF DATA

Relevant EDX findings in this case include:

Discussion

Definition and Classification

The classification of diabetic neuropathies cannot be rigid because many overlap syndromes may be seen. A practical categorization, based on clinical presentation rather than precise etiology, divides these neuropathies into distal symmetrical polyneuropathy (the commonest), asymmetrical polyradiculoneuropathy, cranial mononeuropathy, and entrapment mononeuropathy (Table C7-1). Detailed discussions of all these syndromes are beyond the scope of this section and have been summarized in recent reviews (see Bird and Brown 2002; Brown and Asbury 1984; Harati 1987; Wilbourn 1993).

* Common mononeuropathies with increased incidence in diabetics.

Clinical Features

Diabetic Sensorimotor Autonomic Polyneuropathy

Diabetic neuropathies are by far the most prevalent peripheral neuropathies encountered in clinical practice. Among all diabetic neuropathies, the mixed sensory-motor-autonomic peripheral polyneuropathy is by far the most common, and is usually related to the duration and severity of hyperglycemia. However, this form may occasionally be the presenting symptom of occult diabetes mellitus. The exact incidence of this diabetic polyneuropathy is not known; this is, in part, because of its diverse clinical presentations and different measurements used to define the presence or absence of neuropathy (Table C7-2). The reported incidence of diabetic neuropathy in general is extremely variable, ranging from 5 to 50+. In a large cohort study followed for 25 years, it was estimated that 8+ of diabetics have neuropathy at the time of diagnosis, and neuropathy develops in 50+ of patients within 25 years of diagnosis (see Pirart 1978).

Table C7-2 Available Measures That May Be Used to Assess for Diabetic Peripheral Polyneuropathy

Diabetic Amyotrophy

Diabetic amyotrophy is a much less common neuropathy than the chronic mixed sensorimotor diabetic polyneuropathy. The term was first coined in 1953 by Garland and Taverner. They first called this syndrome “diabetic myelopathy,” because they presumed that the pathology was in the spinal cord, particularly in the anterior horn cell column. This disorder has been surrounded by controversy primarily because of lack of understanding of the exact site and nature of the pathology, which has been attributed to lesions of the anterior horn cells, lumbar roots, lumbar plexus, and femoral nerve. Authors have thus ascribed many terminologies to this disorder, based on their own theory of the nature of the illness (Table C7-3). Although many have suggested that the name “diabetic amyotrophy” be abandoned because of its ambiguity, the term continues to be the most commonly used for this disorder in neurologic practice. Another popular designation is “subacute diabetic proximal neuropathy.”

Adapted with revisions from Wilbourn AJ. The diabetic neuropathies. In: Brown WF, Bolton CF, eds. Clinical electromyography, 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1993.

The site of the lesion and the exact pathophysiology of diabetic amyotrophy are not well known, partially because of the lack of adequate pathologic studies. An inflammatory vasculopathy (vasculitis or perivasculitis) causing ischemic nerve infarction is the most popular theory and is supported by a single autopsy (see Raff et al. 1968) and several nerve biopsy series injury (see Said et al. 1994, 1997). Some observers distinguish between diabetic patients with proximal neuropathy in whom an asymmetrical neuropathy rapidly develops and those with more gradually progressive symmetrical neuropathy. These authors have proposed that the former syndrome is ischemic (vascular) in nature, and the latter metabolic. In practice, many patients fit into a spectrum between these two extremes, making the distinction difficult and two separate mechanisms unlikely.

The following are frequently asked questions regarding diabetic amyotrophy:

Electrodiagnosis

Diabetic Sensorimotor Autonomic Polyneuropathy

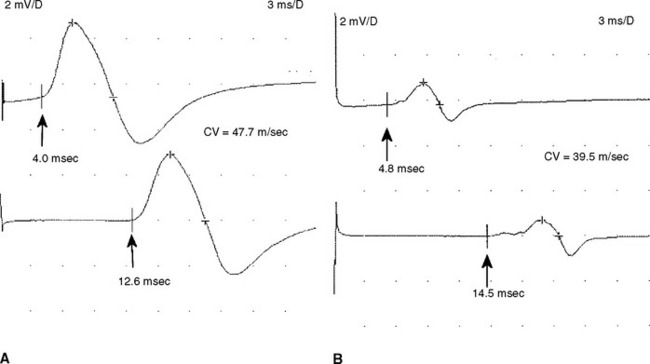

Electrodiagnostic (EDX) studies are valuable in confirming the presence of chronic axon loss peripheral polyneuropathy. During the early stages of the disorder and in a small percentage of patients whose manifestations are restricted to the toes or small fiber symptomatology, the NCS and needle EMG examination, which assess only the large myelinated nerve fibers, may be normal. In these situations, other modalities such as quantitative sudomotor axon reflex test, quantitative sensory testing, or skin biopsy may be necessary to show involvement of small unmyelinated fibers. When large fibers undergo axonal degeneration, the EDX abnormalities are initially found only in the lower extremities. These typically consist of one or more of these NCS abnormalities: absent H reflexes, low-amplitude or absent sural and superficial peroneal SNAPs, low-amplitude tibial and peroneal CMAPs, and mild slowing of peroneal and tibial motor distal latencies and conduction velocities (Figure C7-1). The needle EMG often shows long-duration and high-amplitude MUAPs with or without fibrillation potentials in the intrinsic foot muscles. With more advanced disease, the neurogenic MUAP changes worsen in the leg and ascend that abnormalities are found in the upper limbs. Initially, this usually presents as reduction of the median, ulnar, and radial SNAP amplitudes with mild slowing, low, or borderline median and ulnar CMAPs with mild sensory and motor conduction slowing, with long-duration and high-amplitude MUAPs with or without fibrillation potentials in the intrinsic hand muscles. In severe polyneuropathy there is often complete absence of all routine sensory and motor conduction studies in the legs and hands, with long-duration, high-amplitude and rapidly recruited MUAPs with or without fibrillation potentials in all the leg and arm muscles, which are worse distally.

Diabetic Amyotrophy

Routine sensory and motor nerve conduction studies are abnormal, particularly in the legs, in a majority of patients with diabetic amyotrophy because there usually is a concomitant diabetic sensorimotor peripheral polyneuropathy. Based on electrophysiologic criteria, two-thirds of patients with diabetic amyotrophy have an associated distal peripheral polyneuropathy. In addition to the peroneal and tibial motor NCS, the femoral CMAP should be obtained in all patients with suspected diabetic amyotrophy. Although this study adds little to the diagnosis, it is very useful in assessing the degree of axonal loss. In diabetic amyotrophy, it is frequently low in amplitude, unilaterally or bilaterally, which is consistent with the axonal nature of the lesion. Slowing is, however, minimal. The saphenous SNAPs also should be done bilaterally, although they often are unelicitable in both legs in these patients because of age, obesity, or concomitant distal sensorimotor peripheral polyneuropathy.

Until recently, it was widely accepted that isolated femoral mononeuropathy is a complication of diabetes mellitus. However, it is now clear that this is a misnomer. It is likely that most reported cases, published more than 30 years ago, actually involved mislabeled patients with diabetic amyotrophy; this occurred because many physicians and electromyographers did not assess other muscles thoroughly, in particular the thigh adductors. Although the brunt of weakness in many patients with diabetic amyotrophy often falls on the quadriceps muscle mimicking selective femoral nerve lesions, careful clinical and needle EMG examinations reveal more widespread involvement of thigh adductors and sometimes foot dorsiflexors, muscles not innervated by the femoral nerve. Despite the current knowledge, the term diabetic femoral neuropathy, unfortunately, has not completely vanished (see Coppack and Watkins 1991).

Al Hakim M, Katirji MB. Femoral mononeuropathy induced by the lithotomy position: a report of 5 cases and a review of the literature. Muscle Nerve. 1993;16:891-895.

Asbury AK. Proximal diabetic neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 1977;2:179-180.

Barohn RJ, et al. The Bruns-Garland syndrome (diabetic amyotrophy). Revisited 100 years later. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:1130-1135.

Bird SJ, Brown MJ. Diabetic neuropathies. In: Katirji B, Kaminski HJ, Preston DC, Ruff RL, Shapiro EB, editors. Neuromuscular disorders in clinical practice. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2002:598-621.

Brown MJ, Asbury AK. Diabetic neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 1984;15:2-12.

Chokroverty S, et al. The syndrome of diabetic amyotrophy. Ann Neurol. 1977;2:181-194.

Coppack SW, Watkins PJ. The natural history of diabetic amyotrophy. QJM. 1991;79:307-325.

Dyck PJ, et al. Diabetic neuropathy. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 1987.

Garland H. Diabetic amyotrophy. Br Med J. 1955;2:181-194.

Garland H. Diabetic amyotrophy. Br J Clin Pract. 1961;15:9-13.

Garland H, Taverner D. Diabetic myelopathy. Br Med J. 1953;1:1405-1408.

Harati Y. Diabetic peripheral neuropathies. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:546-559.

Pirart J. Diabetes mellitus and its degenerative complications: a prospective study of 4,400 patients observed between 1947 and 1973. Diabetes Care. 1978;1:168-252.

Raff MC, Sangalang V, Asbury AK. Ischemic mononeuropathy multiplex associated with diabetes mellitus. Arch Neurol. 1968;18:487-499.

Said G, Elgrably F, Lacroix C, et al. Painful proximal diabetic neuropathy: inflammatory nerve lesions and spontaneous favorable outcome. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:762-770.

Said G, Goulon-Goeau C, Lacroix C, et al. Nerve biopsy findings in different patterns of proximal diabetic neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:559-569.

Subramony SH, Wilbourn AJ. Diabetic proximal neuropathy. J Neurol Sci. 1982;53:293-304.

Wilbourn AJ. The diabetic neuropathies. In Brown WF, Bolton CF, editors: Clinical electromyography, 2nd ed., Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1993.