Case 6

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

An electrodiagnostic (EDX) examination was performed.

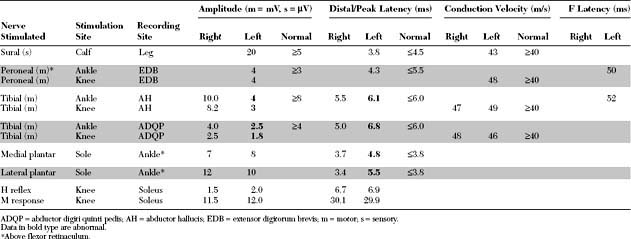

Please now review the Nerve Conduction Studies and Needle EMG tables.

QUESTIONS

EDX FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATION OF DATA

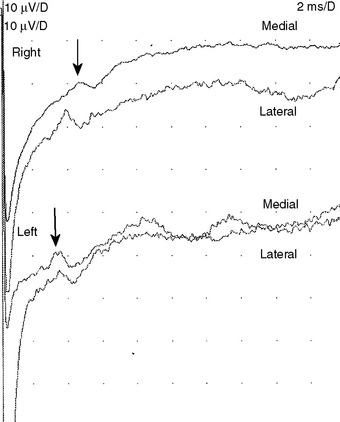

Pertinent EDX studies include the following:

These findings are consistent with a right tibial mononeuropathy at, or distal to, the ankle, affecting both terminal branches (medial and lateral plantar nerves), and compatible with a left tarsal tunnel syndrome (TTS). The study is not consistent with an S1 radiculopathy due to the normal H reflex and lack of denervation in other S1-innervated muscles (medial gastrocnemius, flexor digitorum longus, extensor digitorum brevis, gluteus maximus, and lumbar paraspinal muscles). A sensorimotor polyneuropathy is unlikely because of the lack of denervation in the contralateral foot and normal H reflexes, right sural sensory nerve action potential (SNAP), and left peroneal and right tibial motor distal latencies and conduction velocities.

DISCUSSION

Applied Anatomy

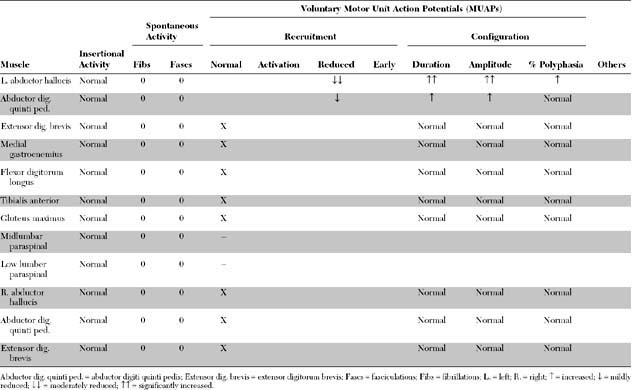

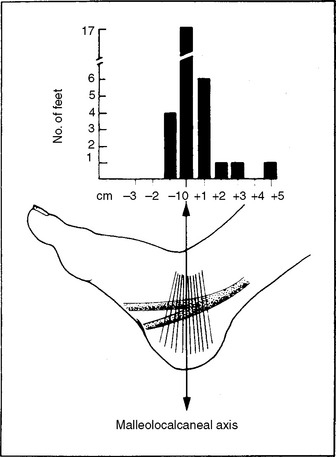

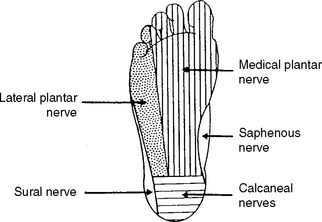

The tibial nerve bifurcates into its two terminal branches within 1 cm of the malleolocalcaneal axis in 90+ of patients (Figure C6-1). Its terminal branches are: (1) the calcaneal branch, a purely sensory nerve, which has a variable takeoff in relation to the flexor retinaculum and explain its involvement or its lack of in nerve entrapments at that site (Figure C6-2); (2) the medial plantar nerve, which innervates the abductor hallucis, flexor digitorum brevis, and flexor hallucis brevis, in addition to the skin of the medial sole and, at least, the medial three toes; and (3) the lateral plantar nerve, which innervates the abductor digiti quinti pedis, flexor digiti quinti pedis, adductor hallucis, and the interossei, in addition to the skin of the lateral sole and two lateral toes. The innervation of the skin of the sole of the foot is provided primarily through the three terminal branches of the tibial nerves, with minimal contribution from the saphenous and sural nerves (Figure C6-3).

Clinical Features

The most common symptom of TTS is burning foot pain, which often worsens after prolonged standing or walking. Sometimes, the pain radiates proximally to the calf. Paresthesia in the sole is common, but weakness or imbalance is extremely rare. The neurologic examination shows sensory impairment in the sole in the distribution of one or more of the three terminal tibial branches (medial plantar, lateral plantar, or calcaneal). In 40+ of patients, the medial and lateral plantar nerves are involved while the heel is spared. In 25+ of patients, the sensory loss involves all three terminal branches territory, and in another 25+, the sensory loss is only in the medial plantar nerve distribution, while selective entrapment of the lateral plantar nerve is only present in 10+ of the cases. The sensory symptoms may be triggered or exaggeration by foot eversion. Tinel sign, induced by percussion of the tibial nerve at the flexor retinaculum, is a useful sign and is present in the majority of patients. Muscle atrophy in one sole is rarely encountered. Weakness is rare because the long toe flexors are intact. Ankle jerk and sensation of the dorsum of the foot are normal.

True TTS is likely a clinical rarity, despite that some podiatrists and orthopedists consider it to be a common disorder. A variety of more common orthopedic, rheumatologic, and neurologic conditions may result in foot pain and may be misdiagnosed as TTS (Table C6-1). The diagnosis of TTS is particularly difficult in patients with a history of foot or ankle trauma. Careful evaluation of the ankle and foot, including x-rays, bone scan, tomogram, magnetic resonance imaging, and EMG, is often necessary before a correct diagnosis is made. Of the neurologic disorders that mimic TTS, proximal tibial mononeuropathy, caused by nerve compression by the tendinous arch of the soleus muscle or due to a nerve sheath tumor, may present with indolent symptoms that are very similar to those of TTS. These rare lesions manifest with foot pain and numbness, but they are usually associated with calf weakness or atrophy and absent or depressed ankle jerk, findings not consistent with TTS. An S1 or S2 radiculopathy, in isolation or as a component of lumbar spinal canal stenosis, may result in foot numbness or pain which is often worse with walking or standing. However, there is usually low back and posterior thigh pain (“sciatica”), depressed or absent ankle jerk or weakness of gastrocnemius, hamstrings, or glutei muscles. A particularly troublesome task is distinguishing patients with TTS from those with early sensory peripheral polyneuropathy, particularly in the elderly. A useful feature is that TTS is rarely bilateral while peripheral polyneuropathy often affects both feet. Also, the sensory loss in polyneuropathy usually involves both the sole and dorsum of the foot and is rarely associated with a Tinel sign at the flexor retinaculum.

* Due to trauma, bunion surgery, foot deformities, or ill-fitted shoes.

Electrodiagnosis

In practical terms, tibial motor NCS, recording AH and ADQP, and medial and lateral plantar mixed NCS should be performed bilaterally for comparison. These should be followed by needle EMG sampling of the AH and ADQP muscles bilaterally for comparison. In a classical case of unilateral TTS, the motor amplitudes are low with delayed distal latencies and the mixed plantar studies are delayed or absent on the affected side only. Needle EMG shows fibrillation potentials in the AH and ADQP muscles with chronic neurogenic MUAP changes on the symptomatic side only. Findings restricted to the medial or lateral plantar nerves do also occur. In these situations, all the NCS and needle EMG abnormalities point to the compressed terminal nerve only. Unfortunately, it has been the experience of many physicians that the lesion is far more likely to be manifested as axon loss only without focal demyelinating slowing. In these situations, none of the above NCS techniques used to diagnose TTS is effective. Instead, the EDX study is nonlocalizing, since the NCS will demonstrate low amplitude or unelicitable responses without slowing, and the needle EMG will confirm the axonal nature by showing neurogenic MUAP changes.

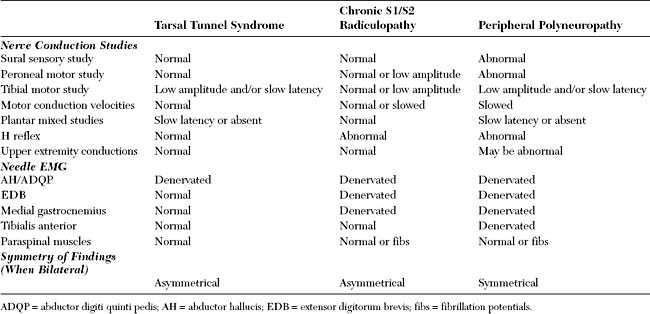

An important task of the EDX study is to differentiate TTS from a peripheral polyneuropathy and S1/S2 radiculopathy. All three disorders have foot numbness and result in abnormal tibial motor conduction studies and denervation of intrinsic muscles of foot. Table C6-2 lists an EDX guide to help in differentiating TTS from these two neurologic disorders. It should be pointed out that distinguishing these three illnesses from one another sometimes is very difficult, especially in elderly patients in whom the sural SNAPs and H reflexes may be absent.

Baba H, Wada M, Annen S, et al. The tarsal tunnel syndrome: evaluation of surgical results using multivariate analysis. Int Orthop. 1997;21:67-71.

Dawson DM, Hallett M, Wilbourn AJ. Entrapment neuropathies, 3rd ed. Boston, MA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 1999.

DeLisa JA, Saeed MA. The tarsal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 1983;6:664-670.

Dellon AL, Mackinnon SE. Tibial nerve branching in the tarsal tunnel. Arch Neurol. 1984;41:645-646.

Galardi G, et al. Electrophysiologic studies of tarsal tunnel syndrome: diagnostic reliability of motor distal latency, mixed nerve and sensory nerve conduction studies. Am J Phys Med Rehab. 1994;73:193-198.

Keck C. The tarsal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg. 1962;44A:180-182.

Oh SH, Meyer RD. Entrapment neuropathies of the tibial (posterior tibial) nerve. Neurol Clin. 1999;17:593-615.

Oh SJ, Sarala PK, Kuba T, et al. Tarsal tunnel syndrome: electrophysiological study. Ann Neurol. 1979;5:327-530.

Pfeiffer WH, Cracchiolo AIII. Clinical results after tarsal tunnel decompression. J Bone Joint Surg. 1994;76A:1222-1230.

Stewart JD. Focal peripheral neuropathies, 3rd ed. New York: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2000.